- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2017 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Captain John McGrath, Royal Navy

This fascinating article received from a Royal Naval colleague covers an often overlooked period of our naval history leading up to the Great Depression. The family background is of itself a lesson in history and we quite possibly have not recognised that an Australian born Olympian, with representation for fencing in the 1920 and 1924 Summer Games, led our Australian Squadron for a brief period during the 1930s. Those with nationalistic tendencies may ask why he did not represent his homeland. The most pertinent reason is that Australia was not represented at fencing in the Olympic arena until 1952.

Family Background

James Campsie Dalglish was born in 1843 in Strathallen, NSW and died suddenly of a heart attack when visiting Melbourne in 1888. He married Marie Sophie de Guerry de Lauret, the elder daughter of a French nobleman the Marquis de Guerry de Lauret. As émigré’s escaping revolutionary France the de Lauret family came to Australia in 1839 and later settled on the Wynella pastoral estate near Goulburn, NSW. James and Marie had six children, four boys and two girls. Robin was the second eldest boy.

James Dalglish had property in NSW and qualified as a land surveyor; as a result, he travelled extensively in throughout the state. He also held a large interest in the Broken Hill Proprietary Mine, providing him with substantial means. With her husband’s unexpected death Mrs Dalglish moved her family to England where the boys were sent to boarding schools, with Robin at the original Oratory School near Birmingham. Marie re-married William Bellasis, from an established Catholic family, and they lived mainly at Sundorne Castle in Shropshire. This was used to help soldiers recuperate from injuries sustained during the Great War. Three of Marie’s sons and one son-in-law died in this war.

Robert (Robin) Dalglish enters the Royal Navy

Robert (Robin) Campsie Dalglish was born at Dubbo, NSW on 3 December 1880. The record of his birth in the NSW Registry gives the place of registration as Goulburn and his first given name as Robert but he seems to have been recorded as Robin on all other documents. His father was James Campsie Dalglish and is mother Marie Sophia(e) Dalglish, néede Lauret. His mother’s maiden name probably explains his facility with the French language, remarked upon favourably throughout his career. The family returned to England in 1888 and Robin joined the Royal Navy on 15 January 1895 in HMS Britannia at Dartmouth. In December 1896, at the end of his time in Britannia, he was awarded the Chief Captain’s Prize dirk1(1). Now rather battered, this was originally a splendid dirk, the blade decorated with blueing, gilding and frost etching. The important part of this decoration, the presentation inscription, has survived well and reads:

Chief Cadet Captain’s prize dirk awarded to Robin Dalglish in December 1896

He was promoted Midshipman on 15 January 1897 and then served in HM Ships Majestic, Pelican and Renown, being promoted to Acting Sub-Lieutenant on 15 July 1900. In the 1901 Census, he appears in the entry for the Royal Naval College, Greenwich, as a Sub-Lieutenant. Having been ill for more than three months with a throat infection while at the College, his navigational sights were deemed inadequate and he was informed that he needed to produce a satisfactory set before he could be further promoted. It would seem that he was given ample opportunity, as his next two appointments saw him serving in destroyers, first in Chatham and then in Portsmouth. He obtained his certificate of competency for promotion in September 1902 and was promoted to Lieutenant on 1 October of that year.

There followed appointments to HM Ships Bacchante and Leviathan (both armoured cruisers of 1901)before joining HMS Shearwater (a sloop of 1900) as her First Lieutenant. He was described by her CO, Commander Crawford, as: ‘A very good 1st Lieutenant’. He then had a short spell in HMS King Edward VII, a pre-Dreadnought battleship, before joining RN College, Osborne, for the training tender HMS Racer.

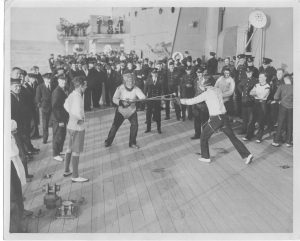

In 1911 Dalglish figures for the first time in the records of the Royal Naval and Military Tournament as the winner of the officers’ bayonet versus bayonet competition, the first time a naval officer had won this competition since its establishment in 1905. Bayonet was another fencing discipline, in addition to foil, épée and sabre, practised in the armed forces until the latter part of the 1950s. Perhaps not surprisingly, his report on leaving, written by Captain Hood in January 1912 draws attention to his skills at fencing and bayonet. In 1912 he married Dulcie Stephen, with whom he had three sons and four daughters. In this year he again figures in the records of the Royal Naval and Military Tournament, this time as the winner of the officers’ sabre competition. He was selected for the British team for the VIth Olympiad in Stockholm to fence in the individual sabre but was unable to compete.

From Osborne he went first to HMS Indefatigable (battlecruiser of 1911) and then to HMS King George V (Dreadnought battleship of 1911) as her First Lieutenant. While in the latter ship, he attended the Kiel Regatta just before the outbreak of World War I. The Flag Officer commanding the 2nd Battle squadron was Vice-Admiral Sir George Warrender and from both ships he recommended Dalglish for promotion. World War I commenced on 28 July 1914 and Dalglish served in this ship until relievedon promotion to Commander on 31 December 1914.

In March of 1915 he joined HMS Victory, additional for HMS Canadabut, as she had not yet been commissioned, he took temporary command of HMS Grafton (an EdgarClass cruiser of 1892) for a four day passage. In April he also had temporary command of HM Ships Magnificent and Mars.These two old pre-Dreadnoughtbattleships were disarmed at Belfast and laid up in Loch Goil and he was in command during this move. Canada had been launched in 1913 as the Chilean ship Almirante Latorre2. She was purchased by the Admiralty in September 1915 and commissioned on 15 October 1915, joining the Fourth Battle Squadron of the Grand Fleet. Dalglish was her XO, and he was to spend most of the war in her. It was in this rank and appointment that he was serving when she participated in the Battle of Jutland (31 May 1916). At this battle, the Fourth Battle Squadron was commanded by Vice-Admiral Sir Frederick Charles Doveton Sturdee and Canadawas in the Third Division consisting of HM Ships Royal Oak, Superb(Rear-Admiral Sir Alexander Ludovic Duff), and Canada. Her part in the battle is probably best described in the words of the official report rendered by her Captain, William Coldingham Masters Nicholson, to Vice-Admiral Sturdee:

H.M.S. “Canada,”

2nd June 1916.

Sir,

In compliance with your signal 1835 of 1st instant, I have the honour to report as follows:—

- On 31st May at 5.10 p.m., the Fleet steaming S.E. by S. in organization 5 disposed to Starboard, the signal was made for Light Cruisers to take up position for approach. At 6.6 p.m. the Fleet altered course to S.E., the Battle Cruisers being then before the Starboard beam engaging the enemy heavily. At 6.10 the signal was made to 3rd and 8th Flotillas: ‘Take up position for approach.’

- At 6.15 formed Line of Battle, S.E. by E., speed being then 18 knots.

At 6.22 three Armoured Cruisers, probably 2nd Cruiser Squadron, were abaft our starboard beam, steaming in a N.N.W. direction, when one of them blew up.

At 6.38 ‘Canada’ fired two salvoes at German Ship, which had apparently suffered heavily, and was much obscured by smoke and the splash of other ships’ fire. Object extremely indistinct. Neither of these salvoes were (sic) seen to fall for certain.

At 6.45 ceased firing.

About 7.15 engaged destroyers about a point before the beam. These turned away, using smoke screen.

- At 7.20 fired four salvoes at battleship or battle-cruiser on starboard beam, very indistinct, probably ‘Kaiser‘ class. Range of first salvo was 13,000 yards, which was very short. Third and fourth salvoes appeared to straddle, but conditions were such as to make it impossible to be certain. This ship then disappeared in dense smoke, probably a smoke screen.

- At 7.25 signal was made to turn 2 points away from enemy, followed 2 minutes later by a second 2 points.

At 7.25 engaged destroyers attacking abaft starboard beam with our 6-inch. Broadside was divided between left-hand or leading boat and the right-hand boat. At 7.30 fired three salvoes of 14-in. on leading attacking destroyer abaft starboard beam. Third salvo appeared to hit. This destroyer vanished in smoke and is believed to have sunk. The right-hand destroyer was also straddled by 6-in. and was lost sight of.

From 7.20 to 7.25 ‘Canada’ appeared (from direction) to be fired at by a battleship of ‘Kaiser’ class, or the ‘Derfflinger,’ on starboard quarter. Shots fell a long way short.

7.35, ceased firing.

7.40, signal was made: ‘Single Line ahead, course S.W.’

- H.M.S. ‘Canada’ was not struck during the action, and there are, therefore, no casualties to report.

I have the honour to be,

Sir,

Your obedient Servant,

- C. M. NICHOLSON, Captain.

The Vice Admiral Commanding

Fourth Battle Squadron.

During the course of the action, Canada expended forty-two rounds of 14-inch ammunition and one hundred and nine rounds of 6-inch ammunition. Shortly after the battle, on June 12 1916, Canadatransferred to the First Battle Squadron. All his reports from Canada recommended him for promotion to Captain. From 25 July to 1 September 1918 he had a temporary appointment in the Second Sea Lord’s Office at the Admiralty and on 31 December he was promoted to Captain.

His sporting abilities had not gone unnoticed and his first appointment as a Captain was as the Director of Physical and Recreational Training. In this role, he had a place on the committee tasked with organising the clumsily named Royal Naval, Military and Air Force Tournament. But he was not content with being an armchair sportsman, as in 1920 he won the officers’ épée competition at the Tournament. In the same year he was thanked by the Danish Ambassador for the help given to officers sent to study British training methods. To cap this year, he was selected to fence for the British team at the first post-war Olympic Games held in Antwerp in 1920. Dalglish put up the best performance of the British team. He reached the second round of the individual épée competition and came 6th in the individual sabre and was awarded a special prize for good sportsmanship. Those were the days of the true sportsman before specialisation, professionalism, money and drugs ruined sport.

Then it was time to go back to sea and renew his acquaintance with his old Captain, Nicholson, now Rear-Admiral Sir William Nicholson. On 1 October 1920 he joined HMS Barham in command and as Flag Captain and Chief Staff Officer to Nicholson, the Flag Office Commanding the First Battle Squadron of the Atlantic Fleet. He obviously thrived in this appointment and received a glowing report from Nicholson who noted his tact, ability and great energy and said the he should ‘…make an exceptionally good Flag Officer’. He was relieved on 18 October 1922. He seems to have made a habit of serving in ships which were later to blow up, first Indefatigable lost at Jutland and then Barham torpedoed in the Mediterranean.

His next appointment took him to command the boys’ training establishment HMS Ganges at Shotley near Ipswich and to be the Captain-in-Charge of the port of Harwich on 1 March 1923. The high state of efficiency at Shotley was attributed to Dalglish, who was noted as having exceptional powers of command and strongly recommended for more important seagoing command by Admiral Goodenough. During his time there, he was again selected for the British fencing team, this time for the VIIIth Olympiad in Paris. Yet again he did well, being the only competitor in the individual sabre event to reach the second round. He was superseded on 15 May 1925. In that year he was the RN Epée Champion.

After a short spell doing the Senior Officers’ Technical Course, he moved to Admiralty to become the Naval Assistant to the Second Sea Lord on 1 July 1926. This appointment marked him out as a definite contender for flag rank. When he was superseded on 25 June 1928, he received a glowing report from Vice-Admiral Hodges, the Second Sea Lord. This drew attention to his firmness of character and tact, to his leadership and initiative, and to his willingness to accept responsibility. He was praised for his social and sporting qualities and recommended for flag rank.

After another short spell doing technical courses, he took command of HMS Centaur as a Commodore, 2nd Class. He was the Commodore (D) in charge of all destroyers of the Atlantic Fleet. In this appointment he again did well being recommended for flag rank first by Admiral Brand and then by Admiral Chatfield. His influence and tact as a leader were specifically commented upon and he is described as having furthered the efficiency of the Atlantic Fleet Destroyer Flotillas and kept them highly efficient and keen. Admiral Chatfield noted that he had put on weight and questioned his physical stamina. This may well be the first indication of future problems leading to his early death.

Arrival Down Under

He was promoted to Rear Admiral on 2 April 1931 and on 28 April commenced the Senior Officers’ War Course, which ended on 24 July of the same year. He did not do well on this course; his report by Vice Admiral Boyle summed it up by saying: ‘I do not think this particular form of study is quite in this officer’s line’. On 12 February 1932, he was lent to the RAN as Rear Admiral Commanding HM Australian Squadron. He relieved Commodore Holbrook on 7 April 1932, hoisting his flag in the depot ship HMAS Penguin and the following day his flag was transferred to the cruiser HMAS Canberra.

All was not well in the RAN, as in common with many other countries as the impacts of the Depression were felt, pay and allowances to government employees had reduced. This impacted ratings on lower pay scales and, a year earlier in the Royal Navy, resulted in a mutiny at Invergordon. This was followed by another similar mutiny in the Chilean Navy, which was run on similar grounds to the RN. The lessons had not yet been learned by the RAN and there was unrest because of what the Lower Deck considered unfair treatment in comparison with other government employees.

On 9 November 1932 media reports were received of a sinister plot to cause disaffection while the main elements of the Australian squadron, comprising HMA Ships Australia, Canberra, Albatross and Tattoo, were in Melbourne. On the morning of the same day in Sydney ratings in HMAS Penguin refused to fall in for work. Quick thinking by duty officers in Penguin promising a sympathetic hearing oftheir grievances and that they would not be punished, quickly diffused the situation and the men returned to work.

There is a further report of 200 men walking off their ships at Melbourne’s Prince’s Pier after refusing duty where they sought to meet with local unionists. While the meeting took place it is unclear whether the men were on duty or were proceeding ashore on leave. The official response was when the ship’s were open to the public they were boarded by Communists directing a conspiracy by distributing material calling for sailors to join hands with the union movement to bring about a mutiny.

The First Naval Member of the Australian Naval Board, Vice Admiral George Hyde, was invited to make a speech at a welcoming dinner hosted by the Lord Mayor of Melbourne. He was cheered when he declared that the assembly on Prince’s Pier had never happened at all. He made a vigorous defence of the loyalty of the sailors and stated that the rumours of dissatisfaction had only come about when the men had been flooded with seditious literature from Communist headquarters.

The Australian Government and the Naval Board had taken a hard line and appeared unsympathetic to any alleged grievances; actions taken by naval authorities in Sydney were seen as weakness. Within days the Commonwealth had mounted a charge against the publisher of the Truth newspaper alleging incitement to mutiny of the crews of certain Australian warships. The case was heard on 23 November when the publisher was found Not Guilty and discharged. At the same time the Naval Board was obliged to take action which addressed most of the Lower Deck grievances. After this the situation returned to normal and a threat of further action was averted. While the overall incident is not well recorded in naval history an excellent summary is contained in the respected newspaper The Hobart Mercury dated 10 November 1932. This is also covered in Tom Frame’s and Kevin Barker’s book on mutiny.

Admiral Dalglish was awarded the CB (Civil) in the New Year Honours List for 1933. Then something else seems to have gone wrong. Allegations of obscene language and drunkenness during a speech at a luncheon at the Millions Club in Sydney were made by the press. These were replied to by Dalglish, who seemed to have wished to sue the paper if it he had been permitted. This is all the more odd given the repeated references to his tact in his personal reports. Perhaps the underlying cause was the threat of mutiny on board Penguin. Whatever the truth, it was made clear to the Admiralty that the Prime Minister of Australia and others of his Cabinet colleagues would not agree to an extension of Dalglish’s service with the RAN. Accordingly, he was superseded on 19 April 1934 after which he took passage to the UK in SS Strathaird, which left Sydney two days later and docked in Tilbury on 1 June. He proceeded to his home, ‘The Homestead’, Woolverstone, Ipswich, on Foreign Service Leave,moving to half pay on completion of the leave3(3).

He died suddenly on 17 December, just a fortnight after his 54 birthday. The causes of death were cerebral embolism and mitral stenosis. This is a sad ending to a most promising career of an officer who displayed great potential and deserved better. He had unfortunately joined the RAN at its lowest ebb and was caught up in unrest and politics not of his own making. At another time his star might have shone and his homecoming deservedly reaching Olympic heights.

Notes:

1 This dirk was included in the exhibition 36 Hours, Jutland 1916, the Battle that won the Warwhich opened on May 24 2016 at the Museum of the Royal Navy, Portsmouth. It was both incorrectly captioned and catalogued.

2 The super-dreadnought HMS Canadawas returned to the Chilean Government in 1920 under her original name of Almirante Latorre. Following a refit in Britain she returned home in 1931 and it is claimed the ship’s company were infected by Communism. After her return the flagship also instigated a mutiny over reduced pay and allowances. This mutiny spread throughout the majority of the Chilean Navy leading to revolution which was put down at great cost. Almirante Latorreremained in commission throughout WWII, being finally sold to Japan for scrap in 1959.

3 In this age of improved medical diagnostic facilities the tragic circumstances of this story might have largely been prevented. Factors such as his father’s early death from heart failure, the youngster being taken from home to a strange land, the death of his three brothers and a brother in law in the Great War would have been taken into account, and also the warning signs of reduction in physical stamina and putting on weight, difficulty in completing a senior officers’ war course and unseemly behaviour at a social gathering.

Sources:

NSW birth registration for Robert Campsie Dalglish, 9516/1881.

NSW marriage registration for James Campsie Dalglish and Mary Sophia de Lauret, 2545/1875.

National Archives: ADM/196/142/356; ADM/196/125/364; ADM/196/46/8; ADM/196/91/30; ADM/171/89/2.

‘DALGLISH, Rear-Adm. Robin Campsie’, Who Was Who, A & C Black, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing plc, 1920–2015; online edn, Oxford University Press, 2014; online edn, April 2014 [http://www.ukwhoswho.com/view/article/oupww/whowaswho/U208259, accessed 28 Nov 2015].

Supplement to the London Gazette, 2 January, 1933, p. 3.

1901 Census, RNC Greenwich.

1911 Census, Osborne, Whippingham.

Binns, Lieut.-Colonel, P. L. The Story of the Royal Tournament(Aldershot: Gale & Polden Limited, 1952).

de Beaumont, C-L, Modern British Fencing(London: Hutchinsons, 1949).

McGrath, John and Barton, Mark, Fencing in the Royal Navy and Royal Marines, 1733 – 1948(Portsmouth: Royal Navy Amateur Fencing Association, 2004).

http://archive.thetablet.co.uk/article/22nd-december-1934/22/obituary, accessed 28 November 2015.

http://www.navy.gov.au/establishments/hmas-penguin, accessed 8 December 2015.

http://www.navy.gov.au/hmas-platypus-i, accessed 8 December 2015.

Frame, Tom, and, Baker, Kevin, Mutiny! Naval Insurrections in Australia and New Zealand(Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 2000) p. 126.

General Register Office, death certificate for Robin Campsie Dalglish, 11 December 2015.