- Author

- Chaloner

- Subjects

- History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- August 1999 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Sluys, in the naval history of England, is relegated to a position of far less importance than the admittedly more exciting battles of Trafalgar, Jutland or Cape St Vincent (Horatio Hornblower and Jack Aubrey were not at Sluys). Yet, apart from its role as England’s first naval victory, the preparations leading up to Sluys were instrumental in bringing about changes which affected much of the structure of English society.

Where is Sluys?

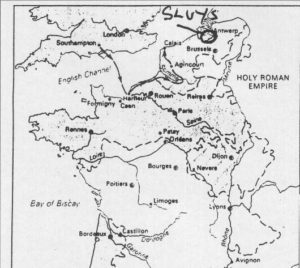

Sluys was the foreport of Bruges in the Low Countries just north of Zeebrugge. It lay in the estuary of the River Zwin which in the 14th Century was a wide stream emptying into the English Channel. Locating it in a modern atlas is difficult. The Belgians spell it Sluis and the town is inland and of little importance. The River Zwin appears to have been lost in reclaimed territory and canals. The French name of Sluys is L’Ecluse which translates to a lock; porte d’ecluse is a sluice gate. Time and tide have wreaked their inevitable toll on so many of the English and European ports which were the assembly harbours for the fleets of The Hundred Years War. Sluys, Winchelsea, Orwell and Falmouth today are little more than seaside resorts.

Background to Sluys and The Hundred Years War

The Hundred Years War may be said to have begun in 1337 when Edward III of England frustrated by the confiscation of Guenne and Gascony by the French King Philip VI promulgated his own claim to the French Crown… for which, in terms of heredity he probably had the better right.

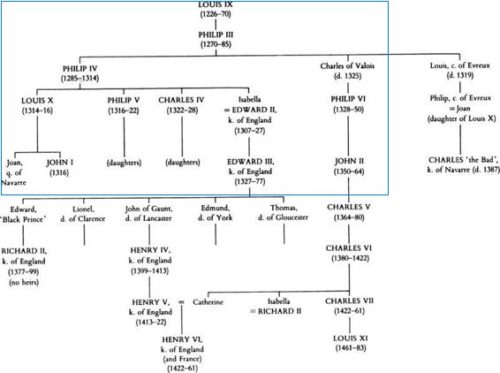

Both men descended from Philip III of France whose eldest son Philip IV ascended the throne in 1285. The latter spawned three sons and a daughter. All three sons followed as Kings of France and they died, one after another, double quick time, bequeathing but daughters to the succession. On the other hand, the girl Isabella, married to Edward II of England, delivered a boy, Edward, who followed his father on to the throne of England.

Philip III’s second son, Charles of Valois, sired 14 children, the eldest of which was yet another Philip who threw his hat or helmet, into the ring challenging Edward of England for the throne of France.

For two reasons the French nobility had voted for Philip VI. Firstly, ever since William of Normandy had conquered England, his successors had looted and ravished France and in fact during the reign of Henry II they controlled the best part of the country. Even though Edward III, born in 1312, at Windsor, 246 years after 1066 and the ninth king since William I, spoke little English, mostly French, he was not welcome. Secondly, in 1328 AD when the ballot was declared the Feminist Movement had not gained sufficient momentum to protest on behalf of Isabella being mother to the King of France and the French have never observed Salique law.

Thus Philip of Valois became Philip VI and immediately moved to occupy those lands in France still attached to England.

Edward III ascended the English throne in 1327 at the age of 13. The Anglo/French question skirmished along for the 10 years of the stewardship of his mother and her paramour Mortimer until the boy sacked them and headed up on the course which eventually devastated the French, Portuguese, Castilian and adjacent countrysides for over 100 years.

Battles at Sea Before Sluys

Excursions across the Channel by privateers had to be ended before any invasion of France could be mounted. Fleets of French ships reinforced by galleys from Castile and Genoa raided Portsmouth and Southampton in 1338; Dover and Folkstone were burned in 1339. British merchantmen trading wool to Flanders and wine from Gascony were regularly pirated.1 England had to win control of the Channel; no simple matter in as much as the exchequer was empty and the fitting out of a fleet was a costly business.

Edward III tried to raise the ante by way of alliances forged in Flanders and with William the Count of Hainaut and brother of his bride Philipa. According to Stubbs, Edward was vain, ostentatious and extravagant. He spent all he collected on futile incursions into France from Antwerp. Stony broke, he was forced to leave his wife and family as security in Ghent whilst he went home to tax his way out of trouble.