- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Sydney II

- Publication

- March 2022 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Andreas Biermann

Battles involving HMA Ships Sydney I and Sydney II illuminate the history of the RAN. Sydney I provided our first major victory of WWI in her epic engagement against SMS Emden and Sydney II is remembered for her early victory in WWII against RM Bartolomeo Colleoni and subsequently her demise against HSK Kormoran. In researching these actions it is important that both sides of the conflict are understood. In Part I of this series (NHR September 2021) Andreas Biermann provided a background to the status of the Italian Navy and in this article he covers the actual battle between the two ships as seen from an Italian perspective.

Operations to June 1940

Having failed to sell Bartolomeo Colleoni to the Imperial Japanese Navy, just prior to the outbreak of war in Europe the Regia Marina recalled her to Italy. After a northbound transit through the Suez Canal in late August 1939 she moved to her new base of Augusta on the eastern coast of Sicily, where she joined her sister Giovanni delle Bande Nere to form the 2nd Cruiser Division (IIa Divisione). In the first week of February 1940, Capitano di Vascello Umberto Novaro was appointed to command Colleoni and in May 1940, the experienced Vice-Admiral Ferdinando Casardi took over command of IIa Divisione, flying his flag in Bande Nere.

The period up to the entry of Italy into the war on 10 June 1940 saw the cruisers carry out standard operations and training, including convoy escorts to North Africa, where Italian forces were being built up. As entry into the war came closer the ageing light cruisers were again considered suitable for inclusion in the battle fleet by the Navy Command. Nevertheless, Colleoni was neither docked nor had time for adequate training of new crew members prior to Italy entering the war, restricting her speed and combat power.

The first Month of War

With the Italian entry into the war, the base for IIa Divisione was moved from Augusta to Palermo on the northern coast of Sicily. The new base was a better location for raids into the Sicilian straits or into the western Mediterranean.

The IIa Divisione commenced war actions immediately, when at 2000 hours on 10 June 1940 the two cruisers sortied from Palermo to cover the laying of the mine-barrage GP in the Sicilian straits between Cape Granitola and the island of Pantelleria, working together with IIIa and IVa Divisione of cruisers and a number of destroyers. On 16 June the AA guns of the two cruisers were in action against a pamphlet-dropping raid by the RAF, which operated against Sicily from its bases in Malta. On 22 June the division sortied again as part of a large operation, including two heavy cruiser squadrons and destroyers, to interdict French maritime movements between Southern France and Algeria, but no French vessels were encountered. On 28 June IIa Divisione moved back to Augusta, in preparation for missions aimed at Malta and/or escorting convoys to North Africa. On 2/3 July a sortie occurred to intercept a Royal Navy destroyer, advised to be making a run from Gibraltar to Malta, but again without result. On 4 July IIa Divisione sortied as part of a convoy escort of an early convoy to Tripoli and returned to Augusta the same day. This was to be the last return to Augusta for Colleoni.

Operation ‘TCM’ and the Battle of Punto Stilo off Calabria 8/9 July 1940

On 7 July 1940 at 1255 hours IIa Divisione under the command of Admiral Casardi in Bande Nere left Augusta to participate in Operation TCM, acting as close escort of a five-ship convoy together with the 10th Destroyer and 4th Torpedo Boat flotillas. TCM was a major convoy operation delivering large volumes of reinforcements and supplies to Benghazi, to strengthen the Italian armed forces in North Africa in advance of an invasion of Egypt. The whole of the Italian fleet was at sea to support this effort, including the modernised super dreadnoughts and all divisions of heavy and light cruisers. Four merchant ships of the convoy left Naples at 1800 hours on 6 July and one from Catania at 1100 hours on 7 July, and IIa Divisione joined them off Sicily that same day.

On 8 July Admiral Campioni, in charge of the operation and commander of the Italian fleet, was notified of the presence at sea of the Royal Navy’s Mediterranean Fleet, and gave orders for the convoy to change course towards Tripoli, to draw off the Mediterranean fleet and prevent an interception. Following an aerial reconnaissance that did not disclose the presence of enemy vessels, the convoy and close escort were ordered to return on a course for Benghazi, meaning that IIa Divisione missed the battle. The Italian main fleet then commenced manoeuvers to bring the Mediterranean Fleet to battle closer to the Italian coast, where the fleet could be supported by the Italian air force, the Regia Aeronautica.

The two fleets met on 9 July, leading to the battle of Punto Stilo. The convoy, which continued to be escorted by Admiral Casardi’s division, reached Benghazi at 1800 hours of the same day without any incident, whence the next day IIa Divisione with the destroyers of 10th Flotilla were ordered to Tripoli, to protect them from exposure to British air attacks on Benghazi expected after the convoy’s arrival.

In hindsight the Battle of Punto Stilo was one of the few pitched battles of the Mediterranean campaign which involved, from the RN – one aircraft carrier, three battleships, five light cruisers and 16 destroyers, and from the RM – two battleships, six heavy cruisers, eight light cruisers and 16 destroyers. The result was indecisive with an equal number of damaged ships and few casualties. Despite the Italian air superiority, they did not make best use of this resource by concentrating on ineffective high-level bombing.

Planning of the Aegean Mission

Following the transfer to Tripoli, some back-and-forth took place in the Italian naval command about the next action to be undertaken by IIa Divisione. On 13 July a shore bombardment at the coastal town of Sollum on the Libyan/Egyptian border was ordered, to be followed by a bombardment of Mersa Matruh further to the east on the Egyptian coast, and then a move, via Tobruk for refueling, to Portolago on the Italian island of Leros, today’s Lakki in Greece. The next day Bulletin 1489 S/RP was sent by air to Egeomil, the Italian military command in the Aegean Islands on Rhodes, alerting it to the transfer of the two cruisers. It is not clear if the message ever reached Egeomil, as the plane carrying it did not arrive on Rhodes until 24 July, after the battle at Cape Spada. The message was however transmitted by radio from both Italy on 18 July at 0935 hours, and earlier from Libya.

Admiral Casardi was informed accordingly on 14 July with a clear and very detailed order, but with a variation cancelling the Matruh element of the bombardment. He was also requested to maintain radio silence while at sea and to transit via the Kythera Channel to the west of Crete at a speed of 25 knots. He was to rely on aerial reconnaissance for safety from encountering enemy vessels during the transfer, although it is not clear whether this refers to the bombardment operations or the transfer to Leros. Critically, Admiral Casardi was ordered to maintain absolute radio silence during the mission. The order also foresaw the possibility to move directly to the Aegean from Tripoli. The cruisers were to be ready to leave Tripoli at short notice on a day to be confirmed, for a mission in the Aegean Sea followed by an indeterminate basing at Portolago on Leros.

The intent of the placement of IIa Divisione at Leros was, in line with the classic raiding role of these fast light cruisers, for the two units to sortie rapidly to disrupt British sea traffic in the Aegean, constituting a permanent threat, with land-based air units from the Egeomil flying reconnaissance for them. Conceptually, this was the classic light cruiser task for which these vessels were designed. That the Royal Navy took this threat seriously is shown by the very substantial close and distant escorts afforded to convoys AN2 and AS2 just a week later.

On 15 July the Italian naval attaché in Istanbul notified Supermarina, the Regia Marina’s high command in Rome, of the passage of three British riverine tankers from the Danube through the Bosporus at 1830 hours of that day, and the presence of some British merchantmen at Cannakkale in the Dardanelles. It was expected that these vessels would attempt to reach Egypt and the Italian naval command decided to activate IIa Divisione as strike force to ambush the expected British convoy. Also on 15 July, Marilibia, the Italian navy command in Libya, had informed Supermarina that the coastal bombardment missions were no longer thought necessary, possibly also because of the time pressure and the impossibility to restock ammunition at Tobruk prior to entering the Aegean.

The Aegean Sea, from 1941 map showing Italian Dodecanese islands noting central position of Leros. National Library of Australia

Supermarina now requested Marilibia to release the two cruisers for operations in the Aegean, signaling that, if agreeable to the command, the Colleoni and Bande Nere could be sent to Leros directly from Tripoli, passing Cerigo (Antikythera) at dawn on the 19th and requesting aerial reconnaissance of the route to Leros. There are unconfirmed claims that one of the messages was intercepted, and that the Royal Navy forces were in a planned ambush position when they encountered IIa Divisione.

At 0930 hours on 17 July IIa Divisione was ordered to leave port, and informed that aerial reconnaissance had been laid on by Egeomil. The order directed Admiral Casardi to leave port at 2100 on the same day, proceeding via a point 30 miles north of Derna and passing the Kythera Strait between the island of Antikythera, or Cerigotto, and Cape Spada on Crete. On arrival at Leros he was to come under the command of Egeomil. The IIa Divisione thus set sail from Tripoli in the evening of 18 July, with a course set to take them north of Crete into the Aegean Sea.

IIa Divisione’s Operation Order

Next to be placed at Portolago, for a short time, were the cruisers Bande Nere and Colleoni, under the command of Rear Admiral Ferdinando Casardi. The operational scope of the placement was to execute raids in Aegean waters to cause maximum damage to enemy traffic in these waters if it should be the case that the English concentrate steamers from Greek or Turkish ports towards Crete.

The division will reach Portolago (Leros) during the early afternoon hours of a day to be communicated only with short notice, leaving from Sollum, where it will execute an improvised bombardment action. It will follow a route passing via the channel between Rhodes and Scarpanto, or via Candia (Crete) and Cerigo.

The Chief of Staff of the Navy, Fleet Admiral Cavagnari

At the same time, the Royal Navy conducted a range of operations in Aegean waters, in preparation for the large convoy AN2 from Egypt to Greece and to protect the merchantmen moving south towards Egypt from Istanbul, the eventual convoy AS2. As it was known that the Kythera Strait was a natural choke point in which submarines were likely to attempt to ambush convoys, the 2nd Destroyer Squadron composed of HM Ships Hyperion (Cdr. (D) H. St. L. Nicholson), Ilex, Hasty, and Hero, conducted anti-shipping and submarine sweep operations north of Crete. They were to be joined at a later stage by Sydney (II) (Capt. John Collins RAN) and her escorting destroyer HMS Havock, who had the task of reconnoitering the sea lanes to the north in advance of AN2. Furthermore, a force of eight Royal Navy destroyers had been assembled to escort the convoy advised by the Italian naval attaché from Turkish and Greek waters. The 152 mm and 120 mm guns of the cruiser and the destroyers all presented a threat to the lightly armoured Italian cruisers, provided that the destroyers could close the distance to their targets.

The Battle of Cape Spada – 19 July 1940

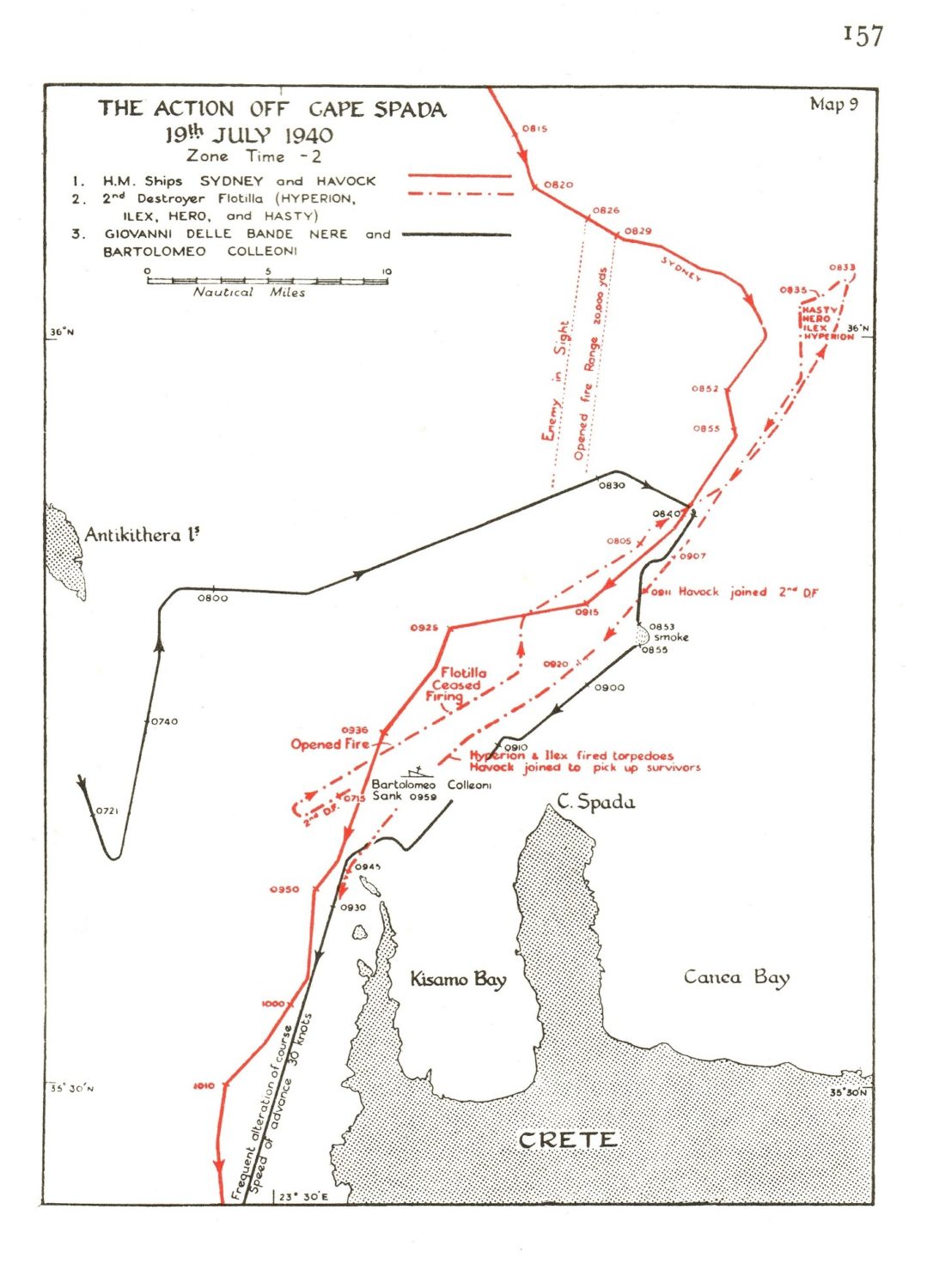

The combination of moves by opposing forces and the absence of radar on any of the vessels turned the action into a classic encounter battle with no tactical pre-battle phase. At 0600 hours on 19 July, after a quiet night passage zigzagging at 25 knots, IIa Divisione was 12 miles southwest of the Kythera Strait steaming on a course of 073 degrees. At the same time, the 2nd Flotilla was six miles to the east of the straits, moving southwest. Sydney and Havock were 60 miles to the north-north-east, moving north towards the Gulf of Athens.

The weather was unfavourable, with heavy seas and a strong southerly wind. This prevented Admiral Casardi from launching floatplanes for aerial reconnaissance without exposing the launching cruiser to a possible submarine attack, as it would have to turn into the wind and slow down while the plane was moved from the hangar to the catapult and eventually launched.

It would also not have been possible to recover the plane. It is likely that he did not consider this necessary anyway, as he had been assured of aerial reconnaissance from Egeomil. However, this was not forthcoming.

At 0617 hours, an hour after sunrise, the cruisers spotted four vessels to the north-east, quickly identifying them as destroyers on a converging course. In turn the 2nd Flotilla also recognised the Italian cruisers and immediately proceeded to inform Captain Collins in Sydney, who acted by turning on a southerly course to support the destroyers of Commander Nicholson. An order from the commander of the Mediterranean Fleet confirming this arrived shortly after. At this stage, IIa Divisione held all the cards, being able to bring heavier fire at longer ranges on the Royal Navy destroyers. But, as noted in Part I, design weaknesses combined with the sea state led to a failure to score any meaningful hit on the multiple targets that presented themselves. In particular, while increasing speed to 30 knots, Admiral Casardi opted to open up the range, rather than close it, because of concern over torpedo attacks and the ability of the 120 mm guns of the Royal Navy destroyers to threaten his cruisers at closer ranges, and a suspicion that another enemy force was lurking to the east and the retreating destroyers were drawing him onto it.

The action commenced shortly after when IIa Divisione opened fire on the 2nd Flotilla at 0627 hours, at a distance of 17,500 m. The 2nd Flotilla executed an about-turn and, picking up speed, quickly moved on a course of approx. 060 degrees to be able to quickly combine forces with Sydney, and opened fire from 0632 to 0643 hours, well directed but 800 m short, while also launching at least two torpedoes at 18,000 m. At this time, IIa Divisione also turned north, eventually on a course of almost due north, increasing the distance to 19,300 m just before 0650 hours when the cruisers ceased fire. No hits had been achieved on the small and fast-moving destroyers who now commenced making smoke while changing course to 090 degrees. The two cruisers accelerated to their realistic maximum speed of 32 knots and started moving in line abreast, Bande Nere leading slightly, and on a course of 085 degrees for a few minutes before turning into line astern and 030 degrees. They opened fire again at 0658 hours at 23,600 m, ceasing it three minutes later at 24,000 m, recognizing the futility and hampered by having the rising sun straight in their direction finders, coupled with a morning haze and remnants of smoke made by the destroyers.

At 0722 hours Admiral Casardi broke radio silence to request Egeomil to dispatch bombers to engage the enemy destroyers. He now decided to close the range and moved on almost 090 degrees until 0730 hours. Shortly thereafter, at 0730 hours, Bande Nere came under fire from a new force to the north, but was unable to see anything other than the muzzle blasts. This was Sydney, which appeared to have better visibility and had opened fire at 18,000 m. The 2nd Flotilla in turn took a course of 050 degrees until about 0733 hours to bring the enemy to fight. The IIa Divisione returned fire on Sydney, but Bande Nere was quickly struck by a 152 mm round, killing four and wounding four, but only causing minor damage otherwise. Admiral Casardi now turned to 135 degrees, making smoke, and the cruisers were firing continuously from their aft turrets even though no good range could be made until 0801 hours, while maintaining an almost parallel course with Sydney, before turning on 180 degrees to try to escape the now combined forces of the Sydney group and the 2nd Flotilla, which at 0733 hours had undertaken another about-turn to move south-west again on a course of 215 degrees.

The hunter had now become the hunted. With no clarity on the strength of the forces bearing down from the north, lack of air support, and already one hit on Bande Nere, Admiral Casardi decided to try and use the higher speed of his cruisers to escape the deteriorating situation by returning towards the Kythera Strait, turning on 215 degrees at 0746 hours following a torpedo attack by the 2nd Flotilla. At this stage, he suspected that Sydney and a Town-class cruiser were reinforcing the destroyers. Gaining director measurements at 0801 hours a running fight ensued, with Admiral Casardi trying to use the higher speed of the Italian cruisers to draw the enemy into the open waters west of Crete while aiming to bring all main guns to bear on the enemy.

RN Bartolomeo Colleoni with her bow blown off and on fire in the final stage of the Battle of Cape Spada. Photo probably taken from HMS Hyperion

At 0821 hours, Sydney was hit by a 152 mm round, causing light damage. Shortly thereafter, at 0824 hours the situation abruptly changed when a critical hit by Sydney was scored on Colleoni at a distance of around 17,000 m. Colleoni signaled machinery damage due to this hit and ended up dead in the water. Her electrical system was gone, disabling the main turrets, even though the central battery of 100 mm guns, operated by hand, continued to fire almost until the end. With the enemy destroyers closing in, she was dispatched by torpedoes within half an hour, the Italian and Royal Navy sources disagreeing about the time of her sinking by over 15 minutes.

Seeing that there was nothing left to do to support the consort, Admiral Casardi now ordered Bande Nere to escape to the south and again requested air support at 0825 hours. The running fight picked up again, with Sydney and destroyers Hero and Hasty chasing Bande Nere for over an hour until 0937 hours. Another hit was scored on Bande Nere, causing casualties and damage including to one boiler, but the design of the Italian cruiser now paid off. Even on five of her six boilers she managed to maintain a speed of 30 knots, increasing to 32 knots by 0916 hours, sufficient to increase the distance to her pursuers. Making for Tobruk, Admiral Casardi decided after an hour and when out of sight of the enemy to change course to Benghazi, which was reached at 2000 hours. The next day she sailed to Tripoli for repairs.

Factors affecting the outcome

The Royal Navy destroyers, sighted at the limit of the horizon, moving north at 31 knots, just below the top speed of the two ageing Italian light cruisers, drew the IIa Divisione along to the north-east into the firing arc of Sydney. That the Royal Navy destroyers remained at long range and just at the very limit of the 152 mm main gun, together with the heavy seas and limited visibility, meant that in these conditions the Italian cruisers fired only a few rounds at very long ranges, and with no effect against the faster enemy destroyers which Admiral Casardi perceived to be running away. Unaware of the general situation, he also believed that the 2nd Flotilla destroyers were aiming to draw his cruisers onto an enemy force located to the east which he could outrun in an encounter by rapidly drawing off north, bringing him closer to Leros as well. Instead, however, his division entered into a pincer between the 2nd Flotilla in front and Sydney and Havockcoming in from the north, forcing him to turn to avoid being overwhelmed and restricting his ability to bring the main batteries of the cruisers to bear.

A significant factor in the run-up to the battle was that Admiral Casardi decided not to launch his floatplanes. Despite the challenging conditions, this contrasted badly with the very aggressive use of the embarked planes by the two cruisers of IVa Divisione during the battle of Punto Stilo just a few days before. It is likely that air support from Egeomil was expected by Admiral Casardi based on the plan of the operation. Nevertheless, no such support arrived in time to participate in the battle, and Cape Spada was thus an early indication of the weak co-ordination between the Regia Marina and the Regia Aeronautica. As a consequence of the failure by Egeomil to intervene, and also this decision, he remained unaware of the presence of Sydney’s force to the north. It is also notable that Admiral Casardi only broke radio silence over an hour after he had been discovered. Given that Regia Aeronautica planes did appear and engage in combat while Colleoni survivors were being rescued, an earlier call for support could have led to them being able to influence the battle.

The battle had shown the weakness of the di Giussanos as gun platforms. The gunnery by Sydney, operating under the same sea and visibility conditions, was superior throughout. The Italian cruisers were able to fire less than 500 shells of which only one hit the Australian cruiser, while Sydney alone fired more than 1,300 rounds, scoring at least five hits. The weak protection of the di Giussanos also contributed to the result – it could stop splinters, but not 152 mm AP shell hits at long ranges, and the vulnerability to 120 mm rounds at shorter ranges dictated the need to keep distance from the destroyers. In the end, Bande Nere had a lucky escape, utilising her superior speed to get out of the trap set by the enemy and escape to Benghazi.

The Aftermath

In total, 121 men of Colleoni’s crew, including her captain, either went down with her or died of wounds later. Over 500 survivors were picked up by the Royal Navy task force and taken to Egypt, with some only picked up over a week later. There were many instances of heroism and self-sacrifice amongst the crew and officers, and Colleoni’s commanding officer, Captain Umberto Novaro, after succumbing to his wounds, posthumously received the Gold Medal for Military Valour for this conduct during the battle.

At his funeral officers of the Allied ships which took part in the battle were pall bearers and he was buried in Alexandria with full military honours.

A number of Italian sailors decided to not surrender, but instead swam to a nearby island, hoping to be taken off by Italian rescuers or being interned by Greek forces. Prisoners taken were interned by Greek forces. Prisoners taken were initially shipped to India, after a stay in Egypt, and at least some later ended up in England.

An important lesson drawn from the battle was that the humanitarian act of picking up survivors came at a cost. It was, rightly or wrongly, blamed for losing the chance to also engage and sink Bande Nere, while it simultaneously exposed the Royal Navy destroyers to bombardment from the Regia Aeronautica, which caused some damage to the vessels, and for the rescue attempts to cease. A report on the actions in the Mediterranean from June to September notes that this was not a desirable outcome, and that commanders would have to harden their hearts in future and act in line with military necessity.

The Fate of the six early Condotierris

Following the action at Calabria, where two of four Barbianos could not participate due to machinery defects and the loss of Colleoni, both of which exposed the weaknesses of these ageing vessels even in a situation where they should have been able to prevail against the opposing force, the surviving units of the class were used almost exclusively for second-line duties. Thus, until their loss they primarily were used as convoy escorts, for minelaying, conducting high-speed transport missions and crew training. Nevertheless, these duties were still very dangerous, and by April 1942 all four da Barbianos as well as the follow-on Armando Diaz had been sunk by Royal Navy action, with heavy loss of life.

From April 1942, of these six early light cruisers, only Luigi Cadorna remained. Unlike many other vessels of the Regia Marina, she was not handed over as reparation, and instead continued to serve as a training ship until she was struck off the Italian navy list and subsequently scrapped in 1951.

Sources

Brenton, R. Mad Aussies of the Med, 14 July 2020, Australian War Memorial

Colombo, L. Colleoni, Con la Pelle Appesa a un Chiodo

Cristini, P., Incrociatori Classe Giussano

Liuzzi, P. G., La Battaglio di Capo Spada, Creta – Grecia Academia.edu

Marina.Difesa.it Umberto Novaro

Marinai.it Pietro Turi

New, A., The Sinking of Bartolomeo Colleoni, 17 July 2018, Australian War Memorial

Stratton, D. Action off Cape Spada July 1940, September 2021, Naval Historical Society of Australia

Ufficio Storico Stato Maggiore Marina Le Azione Navale Tomo I, Rome 1976