- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2014 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Walter Burroughs

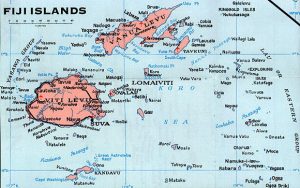

The Fijian Islands are strategically situated in the southwest Pacific straddling the trade route between the eastern seaboard of Australia and the west coast of the United States. Today they are mainly known to Australians and New Zealanders who flock to them for inexpensive holidays. The modern history of these islands is unexpectedly dominated by two naval commodores.

South Sea Island Paradise

There are about 330 islands in the Fijian archipelago, of which only a third are permanently inhabited. The islands are 2,000 nautical miles northeast of Sydney but only half that distance from Auckland. Situated in the tropics, on a latitude similar to Cairns, trade winds provide an equitable climate for most of the year. The migration of indentured Indian labour between 1879 and 1916 has produced a large culturally diverse Indo-Fijian community, now comprising forty percent of the overall population of 860,000. Fiji is a major holiday destination for Australians and New Zealanders with some 700,000 visitors per annum.

European Intervention

Many early European explorers stumbled across various Pacific islands but credit is due to Abel Tasman who in 1643, when transiting from New Zealand to Batavia, placed what is now known as Fiji and Tonga on the map. Both remained largely undisturbed until after the 1788 British settlement of New South Wales which arbitrarily claimed an eastern boundary to include ‘adjacent islands’, which some interpreted as meaning that British sovereignty extended as far east as Tahiti.

As the Fijian people were regarded as warlike and fearsome few Europeans established trade links and those that did were mainly toughened American and British whalers seeking replenishment of food and water. Some Fijians, who were excellent seamen, were taken as crew. Gradually other trades developed in sandalwood and bêche-de-mer. In the 1830s America, Britain, France and Germany began to regularise these trading arrangements through appointments of official agents or consuls whose authority was backed by visiting warships. Various church groups also sought to establish missions. Further complications arose by political ambitions of the Australian States and New Zealand who sought to extend their influence in the Pacific.

The partitioning of the Pacific islands among the colonial powers was haphazard but eventually agreement was reached on specific spheres of influence. The Fijian and Tongan islands were ruled by a large number of native chiefs. In Tonga overall power resided with a proclaimed King George but in Fiji no tribal chieftain could claim overall authority. Chief Cakobau had achieved mastery over a considerable portion of Fiji but had to contend with rival claims by Chief Ma’afu, an agent of the King of Tonga. However it suited the growing number of Europeans to side with Cakobau who converted to Christianity.

Difficulties now arose as Cakobau, who had sought American assistance in putting down a local uprising, was allegedly indebted to the Americans for the then large sum of £9,000. As it was impossible for Cakobau to raise this money he sought assistance from the British Consul, promising to transfer land to the British Crown in exchange. Cakobau relied heavily upon his white secretary John Thurston, an ex-merchant seaman and planter who had been shipwrecked in the islands. By the 1860s the agricultural and labour potential of Fiji was being recognised for the production of copra, cotton and sugar. With the advent of the American Civil War (1861-1865) the supply of raw material to the dominant British cotton industry was disrupted and Fiji was amongst those areas considered as a source of resupply. However the mainly British settlers were unhappy, being unable to ‘persuade’ the newly established King Cakobau to agree to their wishes in the provision of land and labour.

Commodore James Goodenough

James Graham Goodenough’s grandfather was a bishop and his father, a Doctor of Divinity, headmaster of Westminster School. His godfather, Sir James Graham, as First Lord of the Admiralty inspired 13 year old James to enter the Royal Navy in 1830. He gained wide experience serving on the South American Station, in the Crimean War, on the China Station and as an observer during the American Civil War. He had a number of commands and in May 1873 was appointed Captain of HMS Pearl as Commodore of the Australia Station. With education and experience he was a man destined for high office.

Before leaving England Commodore Goodenough and Consul Edgar Layard were selected and briefed on the need for an enquiry into the possibility of establishing a British protectorate over Fiji. The Commodore arrived in Fiji on 16 November and with Layard spent the next five months examining the attributes of the islands and their peoples. Both men saw weakness in the Cakobau Government and sided with the settlers, which further undermined and destabilised local rule. The Layard-Goodenough Report inter alia states:

‘We can see no prospect for these islands should government decline the offer of cession but ruin to the English planters and confusion to the native government.’1

The Imperial authorities, wary of the lengthy and costly Maori Wars, were less enthusiastic in accepting another potential troublesome enclave. Dissatisfied with the Report, its terms were sent to their trusted colonial adviser Sir Hercules Robinson, Governor of New South Wales, for a final decision. Robinson arrived at the then capital of Levuka on 23 September 1874 and on 10 October accepted from King Cakobau the annexation of the Fijian Islands as a British Crown colony. With the 1874 Deed of Cessation the short-lived Kingdom of Fiji ceased to exist, with the Union flag flying amongst the Pacific palms, replacing the dove-with-olive branch motif of the independent kingdom of Fiji. In 1901 Tonga became a British protectorate while retaining its independence as a kingdom.

Thurston, whose role in the treaty negotiations was not widely appreciated by either Layard or Goodenough, was concerned for the future of the natives in his adopted home and sought to place a number of conditions to ensure native rights. Thurston’s main concern was to avoid what had happened to the Maori with what he believed to be usurpation of power by a minority of Europeans claiming title to native land and weakening native culture.

On the Australian Station Goodenough was respected and well liked. He was a keen believer in the temperance movement and abstained from alcohol, and he was attentive to the welfare of his men. A discerning lower deck knew him as ‘Holy Joe’. The Commodore sought to maintain law and order amongst the Pacific Islanders and it was here that he met his untimely death. While trying to reconcile natives in the Santa Cruz Islands on 12 August 1875 he and members of his party were wounded by poisoned arrows. Tetanus set in and he died a few days later aboard HMS Pearl. He was buried in the cemetery of St Thomas’s Church in North Sydney and lies between two of his men. In 1876 Goodenough Royal Naval House was established in Sydney to continue his work in the welfare of naval men. An extensive journal maintained by Commodore Goodenough, providing almost autobiographical details of his extraordinary career, was edited and published by his widow a year after his death.

Sir John Bates Thurston

John Bates Thurston was born in London on 31 January 1836; venturing to sea as an apprentice; he rose to become first officer before contracting cholera. He came to Australia to help recover his health and was for some time engaged in farming. A keen amateur botanist, in 1864 he joined a botanical expedition to the South Seas; his ship was wrecked and eventually he found his way to Fiji. A clash of minds between Goodenough and Thurston was perhaps inevitable with one coming from an outsider’s privileged background and the other an egalitarian who had lived and worked with the islanders in gaining their respect. Goodenough saw Thurston’s influence as unhelpful in affecting change and ensured, at least in the short term, that Thurston’s status in any new administration was diminished.

Cakobau’s maligned Secretary Thurston however continued to serve the new colonial government, firstly as Attorney-General and later as Consul before rising to the position of Governor of Fiji and High Commissioner for the Western Pacific. Thurston, who spent much of his life in the Pacific and deeply loved his adopted homeland and its people, was perhaps one of the most influential individuals that touched the South Seas during this period. His humanity and system of government, which above all respected native rights, is to be found in the principles of government still evident in Fiji today. Unfortunately Sir John’s life too was cut short and he died at sea on 7 February 1897 aged 61 while on passage to Melbourne seeking medical treatment. His mortal remains lie buried in Melbourne’s General Cemetery but his soul is perhaps to be found nearer Suva’s Thurston Botanical Gardens.

Colonial Rule to Self-government

The first governor of the new colony, Sir Arthur Hamilton-Gordon, was previously Governor of Mauritius and would later become Governor of New Zealand. In many ways this was an excellent choice as Hamilton-Gordon was familiar with indentured Indian labour on Mauritius, used to work in the sugar plantations since the abolition of African slavery. He supported an increase of indentured Indian labour and investment by the Australian Colonial Sugar Refining Company (CSR). With plantations helping the economy the Governor turned his attention to creating an enlightened colonial administration with a form of indirect rule designed to preserve and adapt Fijian institutions and prevent the destruction of local culture. Much of this successful work was exported as a model to be used by African colonies.

With steam replacing sail in the later part of the 19th century there was a call for coaling depots and later oil fuel installations to be strategically placed around the world for the benefit of both naval and merchant ships. The seaport and now capital of Suva was to gain prominence as a suitable fuelling depot, especially for naval ships of the Australian and New Zealand Stations. Fiji was also later to become a hub for Pacific cable communications with Cable and Wireless first establishing a base here in 1902. During WW I Fiji was an important port of call for Allied warships but when the threat from the German Asiatic Squadron had passed its importance declined. During WW II Fiji came under the control of New Zealand military authority and with American assistance port facilities and airfields were extended and a flying boat base established. A local battalion was formed as the nucleus of a Fiji Regiment and served in the campaign to regain control of Pacific Islands from the Japanese.

The Indian community flourished, with many migrants becoming permanent settlers even though little land was made available to them. This led to tensions and economic grievances which remain evident to this day. Presently about forty percent of the population are Indo-Fijians. Constitutional development towards independence began in the 1960s. Difficulties arose in finding an equitable electoral system that was acceptable to both indigenous Fijians and Indian residents. In 1970 Fiji became autonomous within the Commonwealth under the able Prime Minister Sir Kamisase Mara. With independence the Royal Fiji Military Forces was formed almost exclusively of indigenous Fijians involved with internal security and policing seaward boundaries. In 1978 a battalion was engaged in United Nations Peace Keeping duties and this support of United Nations initiatives continues to form an important role for the Fijian forces.

In 1987 a coalition parliament was formed with Indian Trade Union support but this led to civil unrest, the parliament was deposed by the military and a republic declared. As a result of this Fiji was expelled from the Commonwealth and lost valuable support from both Australia and New Zealand. A new constitution was promulgated in 1990 designed to concentrate power in the hands of native Fijians. A gradual softening of constitutional changes was made when in May 1999 Mahendra Chaudhry became the nation’s first prime minister of Indian ancestry. Unfortunately this dramatic change to the local political landscape was not to last for long.

Commodore Josaia Voreqe (Frank) Bainimarama

Josaia Voreqe Bainimarama, commonly known as Frank Bainimarama, was born to a chiefly family on 27 April 1954 and educated at the Marist Brothers High School, Suva. He joined the Naval Division of the Republic of Fiji Military Forces (RFMF) on 26 July 1975 as an Ordinary Seaman but was soon selected for officer training in Australia. He returned to naval service in Fiji but was again in Australia for navigation training at HMAS Watson in 1982 and attended the Australian Joint Service Staff College in 1994. In April 1988 he was selected to command the Fijian Naval Force and was Chief of Staff of the RFMF in 1997. In May 2000 he became Commander of the RFMF with the rank of Commodore.

It was inevitable that Bainimarama as Commander of the RFMF would be caught up in the political turmoil. This may have occurred earlier than expected as in May 2000 the European-Fijian George Speight with members of the Special Forces took Fiji’s Parliament hostage for 56 days. Commodore Bainimarama opposed the coup, negotiated surrender of the rebels and handed back power to the civilian administration. However with continued political unrest in December 2006, through a bloodless coup, Bainimarama dissolved parliament and assumed the responsibility of prime minister in addition to his role as commander of the military forces. On 5 March 2014 the Commodore relinquished command of the armed forces in favour of Brigadier Mosese Tikoitoga and this now paves the way for a new general election.

Reflection

Two naval commodores separated by 140 years have stamped their marks on the history of these fascinating islands. The first, Goodenough, could see no prospect for the islands unless they were placed under colonial rule. He was a man of strong convictions who died a martyr attempting to reconcile racial tensions. Next followed a period of gradual economic prosperity mainly brought about through intensive agricultural development using indentured Indian labour. The outcome of this policy, as in many other parts of the world, causes difficulties in assimilating future generations of varying cultures. Bainimarama has, to date, had an impressive career in navigating these difficult waters. In remembering the ideals of James Goodenough and John Thurston we trust the ship of state can be guided into calmer waters and, that the tortuous route to democratic reform will be achieved peacefully.

Bibliography

Bowle, John, The Imperial Achievement – The Rise and Transformation of the British Empire, London: Book Club Associates, 1974.

Docker, Edward Wyberch, The Blackbirders, Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1970.

Encyclopaedia-Britannica,Fiji, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/206686/Fiji/53924/History#ref513704/. Accessed 20 May 2014.

Goodenough, James, Journal of Commodore Goodenough, with a memoir edited by his widow, London: Henry S. King, 1876.

Grattan, Hartley C, The Southwest Pacific to 1900, Ann Arbor MI: The University of Michigan Press, 1963.

Hegarty, David & Tryon, Darrell – Editors, Politics, Development and Security in Oceania, Canberra: ANUE Press, 2013.

Scarr, Deryck, Viceroy of the Pacific – The Majesty of Colour – A Life of Sir John Bates Thurston, Canberra: ANU, Pacific Research Monograph No.4, 1973.

Waters, S.D., The Official History of the Royal New Zealand Navy – New Zealand in the Second World War 1939-45, Wellington: Government Printer, 1956.

Republic of Fiji Military Forces website, http://www.rfmf.mil.fj/ Accessed 20 May 2014.

Note:

1 John Bowle, The Imperial Achievement, p285