- Author

- Lewis, Tom, AOM, Lieutenant RAN

- Subjects

- Battles and operations, Naval Aviation, WWII operations, History - WW2, Aviation

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- May 2020 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Tom Lewis

Dr. Tom Lewis OAM is a retired naval officer, and the author of 14 books. Some of this text was drawn from Carrier Attack, published in 2013 by Tom Lewis and Peter Ingman.

On 17 October 2019, within the Papahana-umokuakea Marine National Monument off the remote Midway Atoll about 1,400 miles northwest of Hawaii, the search vessel RV Petrel found the Imperial Japanese Navy’s fleet carrier Kaga. She was located 5,400 meters (17,000 feet) below the surface. Kaga sits upright and is missing much of the flight deck. In 1942, she was one of the four aircraft carriers which struck Darwin, in northern Australia, in an immense air raid. Akagi, another of the four, was found a few days later.

The Formidable Aircraft Carriers

Japan deployed four of its aircraft carriers against Darwin in 1942. This was no ‘air raid’ as such. The Imperial Japanese Navy had a new wonder weapon at its disposal and used it accordingly. The end result was an overwhelming victory for the new empire of the Pacific. The four ships of the Darwin strike were all used at Pearl Harbor, which had the added capacity of Shokaku and Zuikaku.

The Imperial Japanese Navy pioneered the use of their fleet carriers’ aircraft as a formidable strike force that operated as one. Its effect was to shape a force that could overwhelm whatever target its admirals chose to destroy.

Japan’s first carrier was Hosho, laid down in 1919. She was a small ship at 7,400 tons, but effective enough, and served into WWII, which she survived. Akagi and Kaga came next, much bigger, carrying 60 aircraft each. They underwent a substantial refit through 1934-1938, which increased the number of aircraft carried to 90.

Soryu and Hiryu were of the same class, named after the former. Although nominally the same, they were quite different in detail. Soryu was completed first, in 1937. She was the smaller of the two: her sister ship was completed two years later and was 1,500 tons bigger, at 20,250 tons compared to Soryu’s 18,880. Hiryu was nearly four feet wider (1.2 metres). There were many other carriers built – 25 altogether, not counting seaplane carriers, of which there were four. Hiryu carried two more aircraft: 73 opposed to Soryu’s 71. Generally speaking, Japanese carriers were at the forefront of the marque’s latest ideas, but they were not perfect. Naval historian David Hobbs points out: ‘A major Japanese weakness was the need to strike aircraft down into the hangar to be refueled and rearmed, a time-consuming process in which the operating speed of the lifts was a critical factor that was to prove disastrous at the battle of Midway…’ Japanese aircraft were only brought out onto the deck for take-offs and landings. American carriers routinely parked aircraft on deck, where they could be refueled or re-armed. This meant, for a given size, that Japanese carriers had a lower aircraft capacity.

The aircraft hangars below the main or weather deck were serviced by lifts, which descended to the hangar, or further down to a second hangar, to bring the aircraft up and down. The lifts were complex pieces of machinery, able to carry several tons of aircraft, equipment, and people at a time. Their efficiency was vital to the carrier’s operation of aircraft, for if they jammed or became battle damaged, aircraft would be stranded above and below until repairs were effected. Generally speaking, the hangars were aft at the stern or amidships in the middle of the vessel, with the bow area designated for aircraft takeoffs, which were most likely carried out without the later inventions of catapults and certainly without ski jumps. Aircraft could also be stored along the sides of the carrier for short periods.

Like the US Navy’s vessels, the Japanese carriers had wooden planking decks over a lattice of steel beams, as opposed to British ships, which had an all-steel deck construction. The Americans would pay dearly for this when kamikazes targeted the ‘flat-tops’ in the later stages of the war: the wooden decks were a lot more vulnerable to impact than steel plates. The Americans and British, the operators of large carrier forces in the Pacific, never developed this interesting suicide technique whereby a pilot sacrificed his life for the devastating impact an aircraft crashing into a ship could achieve. Ultimately however, it did not stop the Allied advance.

The longest carrier in the Japanese force, at 855 feet (261 metres), Akagi stretched further than a soccer field – 130 yards/119 metres – and was comparatively massive in breadth and displacement, roughly equivalent to the larger US carriers. Like many aircraft carriers in the world at that time, she was a hybrid ship, a carrier deck built on battlecruiser or battleship lines, in Akagi’s case the former.

Construction and Performance

| Akagi (Carrier Division One)

Name translation: ‘Red Castle’ Year Completed: 1927 Displacement: 41, 300 tons Dimensions: 855’3” x 102’9” x 28’7” Speed: 31 knots Armament 10 (later 8) x 8”/50 Type I 12 x 4.7”/45 28 x 25 mm/60 91 aircraft Crew 2,000 |

Kaga (Carrier Division One)

Name translation: Named after a province Year Completed: 1928 Displacement: 42, 541 tons Dimensions: 812’6” x 106’8” x 31’1” Speed: 28 knots Armament 10 x 8”/50 Type I 16 x 5”/40 22 x 25 mm/60 90 aircraft Crew 2,016 |

| Soryu (Carrier Division Two)

Name translation: ‘Dragon Blue as the Deep Ocean’ Year Completed: 1937 Displacement: 18,880 tons Dimensions: 746’5” x 69’11” x 25’0” Speed: 34 knots Armament 12 x 5”/40 28 x 25 mm/60 71 aircraft Crew 1,100 |

Hiryu (Carrier Division Two)

Name translation: ‘Flying Dragon’ Year Completed: 1939 Displacement: 20,250 tons Dimensions: 745’11” x 73’3” x 25’9” Speed: 34 knots Armament 12 x 5”/40 31 x 25 mm/60 73 aircraft Crew 1,100 |

(Source Nihon Kaigun)

Oddly, she was originally heavily armed with guns – the main armament of carriers being their aircraft – a leftover from her early planning as a conventional line of battle vessel. Even at Midway it would seem she possessed six or eight eight-inch guns.

Kaga’s main problem when in company with the other three carriers of the Darwin group was her lesser speed: 28 knots making her the slowest of the four, the others having 31 knots for the flagship Akagi, and 34 for the two smaller ships Soryu and Hiryu. In a line of advance, the entire strike force would be limited to Kaga’s speed so as to retain cohesion within the protective force of cruisers and destroyers.

Steaming into the wind was a necessary operation for carriers launching or recovering aircraft: it effectively gave 28 knots (or whatever speed the carrier could make) under the wings of the aircraft launching, therefore meaning they were already ‘flying’ at that speed, and so much closer to the speed needed for liftoff. On landing, the wind on the aircraft’s nose effectively meant there was already a brake on the aircraft’s landing.

Kaga’s lesser ability here meant her aircraft were at a disadvantage compared to the other carriers: that three knots when compared to Akagi and the six knots lesser speed for Soryu and Hiryu meant that the Kaga aircraft could not be so heavily loaded with fuel and bombs.

Having said that, Kaga was a worthy ship. She was some 40 feet shorter than the flagship but displaced 1,300 tons more. She carried one less aircraft: 90 as opposed to 91. The two smaller carriers Soryu and Hiryu operated 71 and 73 respectively.

The smaller carriers showed the results of around a further decade of thinking relating to carrier design. Completed in the late 1930s as opposed to the 1920s, they were faster; more efficient in their power delivery than their bigger sisters – so using less fuel – and in Soryu’s case more graceful; she was a purpose-designed carrier from the keel to the island superstructure.

Akagi and Hiryu both – most notably and oddly – had their islands placed to the port, or left, side of the ship. This was related to the constant experimenting which was being carried on in the carrier world at the time of construction. In fact, exactly how an aircraft carrier’s vitals should be arranged would occupy designers for decades more to come.

Sources differ as to the reasoning for the placement: one suggesting it was ‘an experiment in determining whether this characteristic would improve flight patterns when operating a mixed task force of port-sided and starboard-sided carriers.’ Another states that the rationale was as the result of 1930s design studies which showed that ‘turbulence over the flight deck aft (which affected aircraft during landing) could be reduced by moving the island away from the ship’s exhaust gases.’ Yet another suggests ‘the island was placed on the starboard side because early (propeller) aircraft turned to the left more easily (an effect of engine torque). Obviously such an aircraft can execute a wave-off to the left more easily, so the island was put to starboard to be out of the way.’ Another idea was to allow two carriers to operate extremely closely; the left and right islands of a pair allowing maximum visibility as they steamed alongside, but there is no evidence of this from Japanese archives so far.

Akagi even had a downward-pointing main funnel on the starboard side, showing the type of experiments that had been undertaken to control the flow of heated air and how it might affect aircraft performance. Whatever the rationale, these two ships, despite their different class and ten years of thinking in between their construction, spent their lives with their islands to the left. At least their pilots could not get confused and land on the sister ships Kaga and Soryu – landing on the wrong deck is indeed some-thing that has happened in the tremendously intricate world of carrier operations. Akagi and Hiryu remain the only two carriers in the history of the marque to have islands to port. But once the starboard side position was established and a few carriers were built in that configuration, it became difficult to change.

Carrier Defences

By the end of 1941 the biggest threat to the safety of a carrier was aircraft – other people’s, coming your way with hostile intent. It was becoming obvious that the enormous range of aircraft, compared to ships, meant that they could fly long distances and then attack shipping. The big guns of the carrier’s force were ill-suited to anti-aircraft fire, usually lacking elevation to fire upwards to a sufficient height; the reload speed necessary to engage a fast moving aerial target; and accuracy – the solid shell, even when deflected forward of the target accurately, being too small in its frontal area to achieve sufficient hits. Something like a shotgun spread seemed a better alternative.

Consequently, during WWII anti-aircraft defences sprouted from carrier and escort ships like quills from porcupines. They consisted of two main types: quick-firing, small, fast projectiles; and machineguns, preferably of a heavy enough calibre to make a sufficient hole in whatever they hit. While aircraft were sometimes too thin-skinned to withstand such hits, often the projectile passed straight through the aircraft from one side to the other, not making enough damage to bring it down. Many a pilot survived combat in WWI and WWII, bringing home an aircraft shredded with hits but still flying. Pilots found quickly that armouring their cockpits – with seat plates, for example – provided most useful assistance in making it home alive.

The best shipborne AA weapons were the quick firing weapon such as the Oerlikon, with its large 20 mm round most effective if it caught an aircraft in its vitals or hit the pilot. The heavy machinegun – the .50 calibre – also had a spread of shot, a big enough calibre, and sufficient muzzle velocity to do good damage to an aircraft. It was rather like using a shotgun against the flying machines, but it was a big shotgun: smaller calibres such as those of the .303 didn’t do enough damage.

Such weapons were effective, but not to one hundred per cent. Often an aircraft would get through the fusillade of shot fired at it, and successfully fire a torpedo or drop a bomb. Dive-bombers – aircraft diving from a considerable height and releasing a bomb – were a new weapon quickly taken up, given their effectiveness both on land and – hopefully – at sea; proven in the Spanish Civil War with the Stuka, and destined to be a new weapon for the sea war. And so it proved: in the carrier battles of the Pacific and against conventional ships such as the Tirpitz, the dive-bomber was to be an effective if short-lived weapon. The concept was to prove most vulnerable to anti-aircraft weapons, given the attack configuration of descending rapidly in a limited square of sky. While at Midway the dive-bomber struck hard at the Japanese carriers and indeed proved decisive, as warfare technology evolved, so did the dive-bomber’s capabilities diminish, and post-WWII it disappeared from armouries across the world.

Shipborne AA defences had an unintended and bitter but understandable side-effect. Anyone in a ship being attacked by an aircraft, especially if they had seen the consequences of a successful torpedo or bomb strike, was extremely nervous about being the victim of such an onslaught. Consequently, AA crews tended to be quick on the trigger and slow on the uptake as to what it actually was they were firing against. Some aircraft were slow biplanes, and easily enough identified. But most on both sides were fast metal monoplanes, looking similar enough to non-flying people as to be easily confused. Incidents of your side shooting down your own aircraft began in the early years of WWII, and rapidly became worse.

The ultimate AA weapon was however the defender’s own aircraft, deployed far enough away from the strike force so as to ensure insufficient ‘leakage’ of a massive aerial incoming force could not get through to attack the ships. This meant that some aircraft had to be deployed as defending fighters. Obviously they had to be given guidance apart from the aircrew’s own eyes, and radar was seen very quickly as being totally necessary to defence. Radio linked everything together in a complicated but workable solution.

The aircraft were also an attacking force. Three main single engine types were carried by the Japanese fleet. Bombers – the Allied-designated three-man Nakajima ‘Kate’ – which could carry gravity-drop bombs, or torpedoes for anti-ship strike, and Aichi ‘Val’ two-man divebombers, primarily designed for shipping attack. To protect the bombers, the single-seat Mitsubishi ‘Zero’ – the proper designation was ‘Zeke’ – flew with the bomber force and warded off enemy fighters. The range of this strike force was in the region of hundreds of miles, depending on the load carried, superseding the big guns of the battleship, which could fire many miles, depending on the size of the gun.

The Darwin Protection Force

Grouped with every carrier whenever she was in a combat zone was a surface protection force sometimes including an attached sub-sea component of submarines. The purpose of this flotilla of vessels was to protect the carriers – a prime target – and also to let offensive operations be carried out unhampered by hostile combatants.

The Darwin raid group was no exception. Three cruisers – heavy units Tone and Chikuma, and light cruiser Abukuma – were present, the primary task of their big guns was to keep offensive surface vessels at a considerable distance from the carriers. Mitsuo Fuchida, the Air Group commander, and historian Masatake Okumiya also suggest that two battleships, Hiei and Kirishima, were present, although this is not borne out in other sources. It is an odd notation, because Fuchida was writing only 13 years after the raid, and one would presume the presence of two vessels as large as these would have definitely been noticeable.

Cruisers: Heavy, Light and Distant

| Heavy cruisers

Tone and Chikuma Builder: Mitsubishi of Nagasaki Tone completed 1938, Chikuma 1939 Displacement std 15, 200 tons Dimensions: 648’0” x 61’0” x 21’0” Maximum speed: 35 knots Endurance: 8000 nm Armour: belt – 100mm machinery/magazines – 145mm turrets – 25mm Armament: 8 x 8-inch guns 8 x 5-inch guns 57 AA guns 12 x 24-inch torpedoes 5 or 6 seaplanes* Complement: 850 *launching from two catapults, usually including: Aichi Type 0; and Nakajima Type 95.

The design of Tone and Chikuma was quite different to Western cruisers. Their firepower was concentrated forward of the bridge, and the aft end of the ship was kept for flying operations. The six seaplanes they each carried were very useful for reconnaissance, especially when she was working with an aircraft carrier group. The two ships were virtually identical. |

Light cruiser

Abukuma – river name in Tohoku ‘Where the Bears Gather’ Year completed: 1925 Displacement: 5,570 tons Dimensions: 535’0” x 49’0” x 16’0” Maximum speed: 36 knots Endurance: 9, 000 nautical miles Armament: 7 x 5.5-inch guns up to 36 x 25mm AA; 6 x 13mm AA; 8 x 24″ torpedoes 1 seaplane launching from one catapult Complement: 438

Distant cover cruisers Takao-Class Cruisers Takao and Maya Year Completed: Takao and Maya 1932 Displacement: 15,781 tons Dimensions: 661’9″ x 68’0″ x 20’9″ Speed: 34 knots Armament: 10 x 8-inch guns, 8 x 5-inch guns up to 66 x 25mm AA guns 16 x 24″ torpedo tubes Complement: 773 |

(Source Nihon Kaigun)

Destroyers: Urakaze, Isokaze, Tanikaze, Hamakaze, Kasumi, Shiranuhi, Ariake

The heavy cruisers Takao and Maya (both Takao-class) were deployed from Palau from 16 February as distant cover, meaning they were most likely positioned between where it was thought any elements of the ABDA force ships would be. Although details have not been located, this would have been between the main archipelagic islands near the Sunda Strait, as being the most likely choke point through which enemy vessels would have to pass.

A ‘screen’ of seven, some suggest eight, destroyers was engaged to shield the group from submarines. A submarine force was also grouped with the attack force, ironically the three remaining boats of the Sixth Submarine Squadron which had attacked Darwin the preceding month. In an operation which remains a revelation to most even today, four submarines had laid mines and attacked a convoy in mid-month, culminating in an action where one of the vessels – I-124 – had been defeated in a close-range battle with the corvette HMAS Deloraine. The 279-foot (85 metre) boat, with her 80 crew on board, still lies outside Darwin harbour today. The other three submarines had fled, causing the Japanese High Command to think again about a methodology for closing down the northern port. Vengeance for their fallen comrades must have been on the minds of the three other submarine crews on board I-121, I-122, and I-123.

The submarines’ task was also force protection, but in a different manner from the close-range protection the surface ships provided. Roving far ahead, behind, and ‘up threat’ – in the direction from where any danger might emerge – the underwater warriors silently sought out enemy ships that might be trying to close the carrier group and attack. They took good care not to be near the force itself, else the escorting destroyers perceive them falsely as a threat, and attack them: a practice in use today with modern carrier groups.

Flying Operations

Launching and recovering aircraft involved the whole carrier force. The aircraft carriers themselves had to turn into whatever wind was available, to give wind over the wings of the aircraft and therefore help lift them off the decks. Turning large ships such as these called for a lot of searoom, and turning with them was the whole protective force.

Once the aircraft ‘armada’ had been launched – on 19 February 1942, 188 aircraft in total indeed necessitates such a word – the carriers could resume a different course, usually one that took them towards where their aircraft would be returning from, in case any were damaged and low on fuel. This had to be tempered with caution however, as it was usually the direction from where attack might eventuate. Given a strike could take some hours, the carriers and their escorts often would steam in a ‘racetrack’ pattern, a large figure eight, for example. When the aircraft returned the carriers would again have to turn into the wind, this time to lower the landing speed at which the aircraft touched down, to be caught on arresting wires and dramatically stopped. In Darwin the direction of the incoming flight was more known and the steaming pattern altered accordingly.

The intricate complexity of the carrier operations was immense. It resembled a ballet of men, flying machines, weather, and ship operations. Aircraft were brought up from below the deck on lifts somewhat larger than Western carriers, as IJN aircraft did not have as efficient folding wings – the Kates had folded wings, the Vals only folded wingtips. The pilot (and aircrew in the divebombers and vertical bombers) boarded and the engine was started. The aircraft was pushed and pulled into position for takeoff, guided by signalers armed with a complex set of hand movements to signal the aircrew as to how the aircraft should assist with engine and brakes. Once in position the engine was accelerated while the aircraft was held in position by its brakes and restraining cables.

Whether the four carriers which attacked Darwin had catapults is unlikely. One source suggests ‘Japanese carriers also began to be equipped with catapults just before war broke out, starting with Shokakus’. However, another source believes that all takeoffs were deck launches, as Japanese carriers had no catapults.

An aircraft handler would give the final permission for release, and with the engine at full power the aircraft would accelerate at maximum along the deck and into the air over the bow of the ship. Failure of machine or men at this point was usually fatal: a ‘cold shot’ meant the carrier would often run straight over the top of its aircraft, and if the impact of the crash hadn’t killed the crew the ship would often complete the destruction.

Once in the air the pilot was master of his craft to a degree, but he was usually in a formation that would be part of a massed attack. Upon return the aircraft would approach the carrier from astern of the ship, which was steaming at high speed to give a headwind that would assist the landing. Most navies employed a ‘batsman’ at this point who would assist the aircraft pilot by signals, indicating he was too high, low, fast, slow, or off course. An aircraft could be ‘waved off’ at this point, meaning a fly over of the ship, rejoining the line of aircraft waiting to ‘land on’ and having another attempt. Crashes on deck were not infrequent, and for this eventuality – or any other emergency – fire-suited men in helmets were kept at instant readiness, ready to take to a crashed and possibly burning aircraft with fire axes and retrieval of the crew. Fighter pilot Tsunoda Kazuo recalled: ‘To me the most difficult aspect of operations from a carrier was landing on the deck. The tail hook landing was always challenging. There were sometimes accidents and I saw aircraft crash and the pilots were usually killed’.

The Japanese Commanders

At the start of 1942 the Japanese carriers of the First Mobile Striking Force were the most powerful naval force on earth. Referred to more simply as Mobile Fleet, it was commanded by Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, who flew his flag from the carrier Akagi.

Some sources refer to Mobile Fleet as ‘Nagumo’s Carrier Task Force’ or ‘Nagumo Force’. However, Nagumo himself had little to do with his own air operations. While a competent officer, he was ‘largely passive and not terribly innovative’. Little if nothing of the success of the force can be attributed to Nagumo. It was rather a case of being in the right place at the right time: he was commanding a superior weapon system which was employed using an effective and successful doctrine. While the Pearl Harbor attack was a celebrated success, Nagumo failed to order a further strike. This may have crippled the base infrastructure, and according to Admiral Nimitz could have lengthened the Pacific War by another two years.

Fortunately for Nagumo, he had a number of talented officers serving under him who were deeply committed to the development of high quality, massed naval airpower. The stand-out was Nagumo’s air officer, Commander Genda Minoru, who has attracted superlatives such as ‘brilliant’ and ‘house genius’. It was Genda who first pushed for the carriers to be grouped together in a single command. It was also Genda who had designed the daring Pearl Harbor operation, so he was largely responsible for developing the air doctrine that enabled aircraft from different carriers to operate together effectively as a single force. As this was so new, there was nobody else suitably credentialed to critique his plans. Nagumo himself was certainly unable to do so. Hence the air operations of Mobile Fleet ‘were disproportionately the responsibility of a single individual’.

The core architect of the Darwin air strike was undoubtedly Genda. However, he had a cadre of very experienced and capable aviation leaders. Chief among these was Commander Fuchida Mitsuo, who had famously led the Pearl Harbor attack. Fuchida himself led the B5N Kate unit on Akagi. Also from Akagi was a veteran fighter pilot who led the Zeroes, Lieutenant Commander Itaya Shigeru. Another influential officer was Lieutenant Commander Egusa Takashige, who led the D3 Val unit onboard Soryu. He was the recognised Japanese expert on dive bombing. Further, Genda respected him as being a ‘God-like’ combat leader. Egusa had led the crucial second wave dive bombing attack against ships at Pearl Harbor. Indeed, virtually all of the flying leaders at Darwin were Pearl Harbor veterans. At least 80% of the aircrews themselves must have been similar veterans.

The Darwin raid would be the first time the carriers of Division 1 (Akagi and Kaga) and Division 2 (Hiryu and Soryu) operated together since Pearl Harbor. Indeed, the Division 1 carriers had initially returned to Japan. They then faced only insignificant opposition during raids against Rabaul and the wider New Guinea area in January. It was in reference to these raids that Fuchida made the comment ‘if a sledgehammer had been used to crack an egg, this was the time’. Certainly this was a curious use of the force at this critical time, especially given that the two carriers of Division 5 (Shokaku and Zuikaku) had also participated. Thus in the two months following Pearl Harbor, Akagi and Kaga steamed long distances but faced only negligible opposition.

It was early February when they arrived at Palau and made rendezvous with Hiryu and Soryu. These carriers had detached after Pearl Harbor to support the Wake Island occupation. So the best carriers of Mobile Force were again reunited and the first mission was to strike Darwin. Douglas Lockwood, writing the first book on the raid, and interviewing the aviator, claimed that Fuchida saw Darwin as similar to Rabaul, and thus the sledgehammer and egg metaphor was again valid.

However, it is clear that the Japanese recognised the strategic value of Darwin in regard to their operations in the Netherlands East Indies. The Japanese Navy General Staff had approved the attack as soon as possible after Pearl Harbor. Genda himself recommended that it be the first target. The commander of Carrier Division 2, Rear-Admiral Yamaguchi, wanted to attack Darwin himself using only Hiryu and Soryu. He first made this proposal on 20 January, when the Division 1 carriers were far away in the New Guinea area. However, it is also recorded that Yamaguchi’s reasoning made reference to a surprise attack by American destroyers on a Japanese convoy off Balikpapan. He wanted all bases within a radius of 600 miles of intended operations to be attacked. Darwin was certainly within such a radius in regard to Timor, for example.

The Japanese could have attacked the northern capital much earlier. Yamamoto himself made it clear that four carriers would be used, even though it meant delaying the attack. Accordingly, on the afternoon of 9 February Yamamoto sent Southern Force Telegraph Order No. 92 to the carriers. This assigned Mobile Fleet to attack Darwin one day before the invasion of Timor was planned to commence, around 19 February. The order also comprised a second part which sent Mobile Force into the Indian Ocean to destroy enemy forces south of Java.

These plans make it clear that Darwin was considered an important target. Genda said simply ‘the planning was a comparatively easy task’. He had good intelligence regarding the target, and did not expect serious opposition. Perhaps this overconfidence led to what was perhaps the only oversight during the operation. During attacks elsewhere, the Japanese were meticulous in attacking all air bases in the vicinity of the target. However, at Darwin they failed to attack Batchelor, just 50 miles south of Darwin – less than 20 minutes flying time for the bombers. Batchelor was very significant in that it was used by American heavy bombers. RAAF Wirraways had been dispersed there from Darwin. Batchelor was also the only location outside of Darwin to be allocated AA guns. So this oversight is unexplained, especially as the field would usually be easily seen from the air given the relatively thick surrounding jungle.

The Japanese Strike Weapon

The Japanese carriers had one unique advantage over any other carrier force in the world: they combined their aircraft into one formidable weapon, to be used decisively against any target. Other carrier-operating nations had not yet understood and undertaken this tactical idea. Given all of the aircraft from any Japanese carrier force – at Darwin 188 aircraft operating against a target of town and shipping – this meant the air fleet armada was virtually unstoppable. No matter how good the defender’s countermeasures were, and at Darwin they proved not to be very good, the counter-measures would be overwhelmed, and the target swamped and devastated.

The first years of WWII had at first seemed only to confirm the supremacy of the ‘big gun’ ships. The British leader Churchill fretted about the likes of the raider Bismarck and whether the Germans would employ the newly surrendered French battleships. Naval operations and sea power were still defined around the capital ships. But in November 1940 the Royal Navy launched the first entirely carrier aviation anti-ship strike of the war, when Italian battleships were sunk or disabled in the port of Taranto. This effectively put the potentially powerful Italian capital ships out of the war, and helped secure the balance of power for the British in the Mediterranean. The strike weapon that produced this stunning result was just 24 fabric-covered biplanes flying from a single carrier – perhaps a force more likely to have been thought useful for scouting than as a strike force.

Such a stunning result did not go unnoticed by the Japanese, who studied Taranto closely. It ultimately led to the formation of the First Air Fleet in April 1941: for the first time carriers were being combined together as was natural with the big gun ships. This has been called a ‘truly revolutionary development’ that transformed naval aviation from an ancillary role to ‘a decisive arm of battle’. Within months this led to the well planned and perfectly executed Pearl Harbor strike.

The Japanese were the first to combine the air fleets of multiple carriers into a single strike force. Even until Midway and beyond, the big American carriers operated independently – indeed, depending on the carrier itself, some squadrons from a single carrier were unable to execute properly coordinated attacks. The Japanese, however, were able to get multiple squadrons from multiple carriers into the air at one time, and co-ordinate them successfully to overwhelm a designated target. At Pearl Harbor, two strikes were launched from an unprecedented six big fleet carrier decks. Both strikes comprised a mix of fighters, dive-bombers and torpedo bombers (also used as conventional ‘level’ bombers). Including the fighters that flew combat air patrols over the carriers, an incredible force of over 400 modern aircraft was utilised during the operation.

Pearl Harbor is remembered as the ‘day of infamy’ which began the Pacific War and brought the United States into WWII. However, it was revolutionary in fully utilising this newly discovered combined power of carriers for the first time. Matching Japanese military doctrine perfectly, the carriers delivered overwhelming power to a particular point in a surprise attack, hoping to deliver a knock-out punch. They did deliver a hefty blow to the American battleships, but the great irony was that they missed the only force that would ultimately reckon with them on anything like equal terms: the US fleet carriers.

But after Pearl Harbor, the six great Kido Butai carriers were fated to never again operate together. Five of them combined together in the Indian Ocean in April 1942. However, due to damage and aircraft losses to the two Division 5 carriers at the Battle of the Coral Sea in May, at the crucial Battle of Midway the following month only four of the major fleet carriers could be assembled. These were the same four carriers of Division 1 and 2 that attacked Darwin in February. In this respect, the attack on Darwin counts as one of the few great carrier raids mounted by the formidable Combined Fleet before it was decimated at Midway.

The Darwin raid was unusual in comparison to the other big raids. Recently, and drawing on contemporary Japanese sources, authors Jonathon Parshall and Anthony Tully have pointed out that a critical practice in Japanese carrier operations was ‘deckload spotting’, whereby half of the potential aircraft force could be launched at one time. The lighter aircraft, namely the Zero fighters, would be spotted forward as they needed much less deck-length to take off. The heavier aircraft, the two-seat divebombers (D3A1 ‘Vals’) and three-seat attack bombers (B5N2 ‘Kates’), would be further back. But only about half of the aircraft on a single carrier could be assembled on the deck at any one time. At both Pearl Harbor and Midway, such ‘deckload’ strikes were launched. This meant that the first strike at Pearl Harbor comprised 180 aircraft, or about half the full attack strength. A second wave was launched afterwards with the remainder of the aircraft.

Darwin was unusual as a maximum strike was launched in a single wave. Thus the first half of the strike was launched, and kept waiting while the remaining aircraft were brought up from the hangar deck. This was quite a complex business, as each elevator brought up one aircraft at a time, which would then be manhandled into a precise position on deck. Parshall and Tully refer to this practice of launching the entire air group as being ‘probably impractical’ as the first wave would burn up precious fuel waiting for the second wave to join them. They suggest it would take at least half an hour to complete. In fact, this appears to be exactly what happened during the Darwin strike. Japanese records refer to a three-Zero Combat Air Patrol being launched at 0615. Commander Fuchida, the same famed leader of the attack force who led the Pearl Harbor strike, took off in his B5N attack bomber from Akagi at 0622. Most likely he followed the nine Zeroes from his carrier, and possibly some of the lighter divebombers as well. But after takeoff, his aircraft did not depart from the vicinity of the carriers until 0700, almost three-quarters of an hour later. This is consistent with waiting for the second deckload of aircraft to be brought up, spotted on deck and launched from each of the four carriers.

Given the changed circumstances, it is most likely that both deckloads were spotted differently on 19 February, and probably did not comprise evenly balanced proportions of aircraft. Other factors, such as cruising speed and overall range would have been taken into account. One source suggests the divebombers took off last, and used their faster cruising speed (as compared to the Kates) to catch the main force en route. However, the take-off times quoted vary hugely with that given in the Japanese Official History. Also, technicalities, such the fact that the Vals could only use the middle elevator due to only having folding wing-tips, rather than full folding wings (such as the Kates), meant that a selection of aircraft in each deck-launch was more likely. This is consistent with the Zeroes being stowed forward in the hangars, the Vals midships, and the Kates, which needed the greatest deck-length for take-off, were aft.

So why was Darwin different in having just a single, maximum aircraft strike? Clearly, the recent experience of Pearl Harbor loomed large in the minds of the Japanese planners. Among other things, most of the aircraft losses at Pearl Harbor were in the second wave, after the defenders had been fully roused, angry, and fighting back as hard as they could. Surprise would pay dividends and minimise losses. Besides, a second strike was planned to take place anyway, only with land-based bombers at high altitude. These would go in unescorted as the carrier strike would destroy any local fighter opposition, which the Japanese knew would not be significant. Evidence of the Japanese disregard for Allied air strength was a Combat Air Patrol of just three Zeros being maintained over the carriers during the day (from a total pool of 15 aircraft held for this purpose). This is consistent with expecting, probably at most, a prowling flying boat or reconnaissance aircraft.

Darwin was always seen as a raid against a relatively weakly defended target. As Fuchida would later famously comment: ‘It hardly seemed worthy of us. If ever a sledgehammer was used to crack an egg it was then’. So there was never a need to consider a second carrier strike. Also, a single strike allowed the Mobile Fleet to do their business and return north as quickly as possible, thus limiting their exposure near Allied territory. Lingering in the area increased the possibility, however unlikely, of enemy attack by some means. Finally, because of the perceived weakness of the target, the carriers could get reasonably close to the target, thus permitting the luxury of extra time in the air burning fuel. The Japanese plan was to launch the strike at a point 80 miles south of Babar Island, well into the Arafura Sea. This gave an approximate range to target of around 200 miles. This is similar to other raids flown at this time – Pearl Harbor was also launched from a similar range of 200 miles.

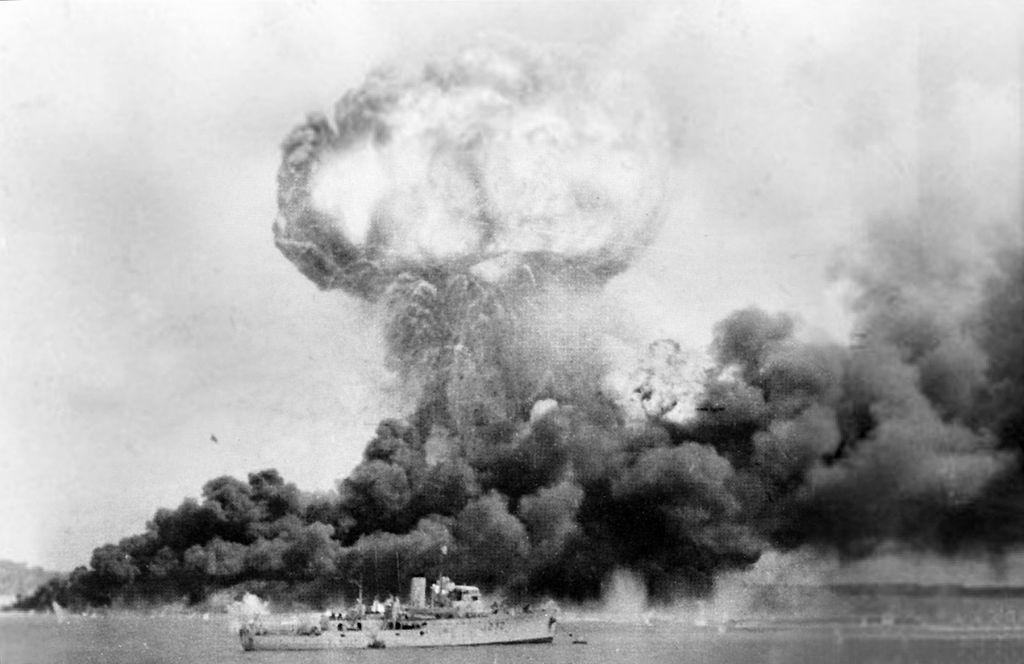

The air raid launched from the four carriers was a great success. It smashed Darwin’s infrastructure, including its only substantial wharf; sank 11 ships, destroyed 30 aircraft, and killed 235 people. Soryu, Hiryu, Akagi and Kaga sailed away, having lost only four of their aircraft. But it was to be a short-lived victory. In June 1942 all four of the ships were sunk at the Battle of Midway.

Editorial Note

For reasons of brevity the many footnotes used in the original text have been omitted from this paper. Copies of the original with footnotes are available on application to the Editor.