- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - general, Naval history

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2019 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By John McGrath

For the great enemy of the truth is very often not the lie – deliberate, contrived, and dishonest – but the myth – persistent, persuasive, and unrealistic. Too often we hold fast to the clichés of our forebears. President John F. Kennedy

It will not be long before any serious student of naval swords will be presented with some ‘facts’ with absolutely impeccable pedigrees. Tact is the main requirement while the informant’s information is corrected. Perhaps the time has come to see if dissemination in a respected publication, such as the Naval Historical Review, will reduce the frequency with which these myths are paraded.

The first of these assertions is made of many other types of swords as well as those from the Royal Navy. It is the well-rehearsed story that the grooves running along the flats of the blade are ‘blood grooves’, ‘blood channels’ or ‘blood gutters’ and that they serve either to allow the blood of a transfixed opponent to flow more readily, presumably to speed his death, or to reduce the suction that makes it difficult to withdraw the weapon for another thrust. Although such ideas are gory enough to appeal to a bloodthirsty young lad playing pirates, the truth is much more prosaic. An ideal sword blade combines lightness with stiffness and the grooves contribute to achieving both of these. Perhaps counter-intuitively, removing material from a bar of metal increases its stiffness; this is the principle behind the ‘I’ beam.

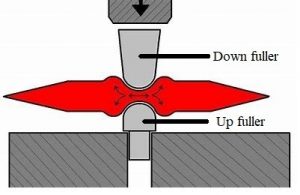

The correct term for these features is ‘fullers’. The origin of this terminology is related to blacksmithing where the process of grooving is termed ‘fullering’ and is executed with tools known as fullers. When forming a fuller on each side of a flat bar, as for a sword blade, a pair of fullers is employed; the lower termed the up fuller and the upper called the down fuller, Fig. 1.

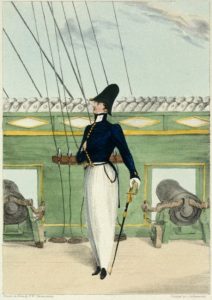

Next is the almost unshakeable belief that midshipmen always used dirks. This is regularly reinforced by historical novels, television and cinema. Until 1805, in common with other warrant officers and officers, they could wear and fight with whatever they chose. In that year, regulations governing swords were first introduced. For lieutenants, warrant officers and midshipmen, the sword had a stirrup hilt, a black fish skin grip and a plain, rounded pommel, Fig. 2.

Midshipmen were to wear such swords of suitable size. However, because most young men did not achieve the status of midshipman until their later teenage years or even after that, they were essentially fully grown and would not have needed shorter swords. However, such smaller swords are often encountered and then attributed to midshipmen. While it is possible that some were the weapons of those young men, many more were probably lightweight, dress versions of the uniform sword for wear when the fighting weapon was unnecessarily bulky. Fig. 3 shows a midshipman of 1823 wearing his 1805 Pattern sword.

New patterns were introduced in 1827 and from this date all officers and midshipmen had the same version with a pipe-backed blade, a white fish skin grip, and a pommel in the form of a lion’s head, Fig. 4.

Except for variations in the design of the sword blade, scabbard and sword knot, the situation remained unchanged until 1856. At this date the dirk became the uniform weapon for the midshipman. There is no known pattern weapon, so the details of the design can only be deduced from surviving examples. It had a straight blade about 13½ in (340 mm) long by 1¹/₈ in (29 mm) wide and simple, recurved quillons terminating in acorns. The grip was white fish skin and the pommel was in the form of a lion’s head. The dirk was carried in a black leatherscabbardwith two gilt mounts, the upper of which carried a frog stud. In 1879 the dirk blade was lengthened to 17¾ in (451 mm) and was blued and gilt. It also acquired the oval medallion incorp-orating a crowned and fouled anchor in the centre of a laurel wreath which decorates the cross piece. The locket of the scabbard no longer had a frog stud but two loose rings, so that the dirk could be suspended from two short slings attached to the waist belt. The regulations were re-issued in 1891 with a few clarifications and it is after this date that the decoration on the blades is etched rather than blued and gilt, matching the decoration on contemporary swords, Fig. 5.

So who wore the numerous dirks, straight and curved, toy-like and weapon-like, which are so frequently attributed to midshipmen? The dirk was not just a weapon but a multi-purpose tool useful in cutting cordage and canvas as well as for eating and,in extremis, as a weapon. In this guise, they may well have been owned by midshipmen but not as part of their uniform. Volunteers first and second class wore dirks in uniform but no patterns survive and some senior officers carried them as a badge of rank, more convenient to wear than a sword.

Another generic myth concerns the small brass disc inlaid into the blade close to the shoulder, Fig. 6, that is often marked PROVED or PROOF. It is definitely not, as is often claimed, proof that the sword has been bent so that the tip touched that point. Even the simplest calculation shows that at the very best the result would be a hopelessly bent sword or, much more probably, a very broken sword.

During the nineteenth century a number of scandals, when some patterns of bayonets and some cavalry troopers’ swords were of such poor quality that they bent when used, led to the development in 1844 by Henry Wilkinson of machinery to test swords and bayonets to ensure that they were fit for purpose. Weapons that passed were stamped by government viewers. Officers always purchased their own swords and these were not subjected to this government quality assurance system. Sometime after 1844 the firm of Henry Wilkinson introduced the circular brass proof mark bearing the initials ‘HW’ set into the shoulder of the blade to indicate that he or his assistant had personally tested the sword, Fig. 6. For naval swords this may have been coincident with the introduction of the flat-backed blade in 1846. In 1854 Wilkinson began numbering his blades serially as an additional quality assurance measure.

The use of the brass proof mark rapidly spread to other sword makers, many of whose products were of dubious quality. So it remained a case of caveat emptorfor an officer purchasing a sword.

The final myth is that naval officers wear their swords on slings and carry them at the trail as a mark of disgrace for ungentlemanly behaviour during a mutiny. Oddly, nobody seems to be able to name the mutiny or to describe the behaviour. Let’s start with mutinies. The great naval mutinies of Nore and Spithead took place in 1797, eight years before uniform pattern swords were introduced for officers. It would, therefore, have been impossible to order officers to wear their swords in any particular style. Next, ask the question: Why on slings? The answer is simple: so that you can ride a horse. Just look at most of the uniforms until the advent of battledress in World War II and the pullover in the 1970s; they were designed for riding and had slits up the backs of the coats to facilitate wear on horseback. Then consider the Army. Swords were carried on slings by all officers until the invention of the Sam Browne belt in the late nineteenth century made it possible to wear the sword close to the waist and to mount a horse. Fig. 7 shows a nineteenth century infantry officer’s sword with the loose rings on the scabbard for wear with sling.

Cavalry officers still wear their swords on slings, as do general officers when wearing the Mameluke-hilted dress sword and officers of those regiments, e.g. the Guards, which still retain full dress uniforms. There are suspicions that this rumour started with the gunnery staff at a well-known naval officer training establishment in the West Country, but there is no definitive proof to that effect. Wherever it started, ignore it and refute it; fight rumour with fact.

Source of quotation:President John F. Kennedy, commencement address at Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut, June 11, 1962. Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: John F. Kennedy, 1962, p. 234.