- Author

- Rivett, Norman C

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, Naval technology, Garden Island

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2012 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Foreword

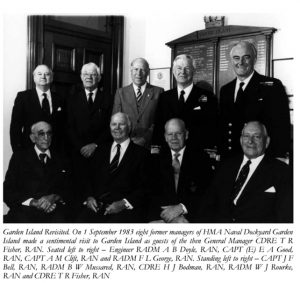

In the century past (plus two more years, until 10 May 1989) Garden Island was a Naval Dockyard managed by a succession of twenty six Naval Engineering Officers of various titles and ranks. All were capable men and it has been my good fortune not only to have known fourteen of them but to have worked for eleven of these. Most of the RAN managers had prior dockyard service as deputy or assistants to the manager, some on more than one occasion.

The nominal term of appointment was for five years but for a variety of reasons this was not always the case.

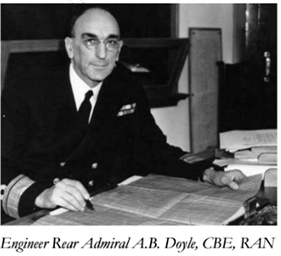

The longest serving manager was Alec B. Doyle, whose notes have been used in compiling this article. Doyle occupied the position for 8 years 9 months and 16 days; a close second was G.H. Bromwich, who served for exactly 8 years. These two men held office during the difficult period of two World Wars, with Bromwich being General Manager during WW I and Doyle General Manager during WW II.

The following account of engineering events in the RAN in general and at Garden Island in particular has been faithfully transcribed, I might almost say deciphered, from Doyle’s handwritten notes. Comments and minor corrections have been made as footnotes, particularly in relation to names, positions held and dates where memory may have failed him.

Naval Odds and Ends mainly concerning Garden Island

It has been suggested to me that many of the present generation would not know, unless interested in naval history, that the first entries of Engineer Officers in the Royal Australian Navy were of Engineer Officers of the Merchant Navy. As far as I know, Clarkson, McNeil, Braud, Hogan and others came from the Merchant Navy and I think the best among them would have held Extra Chief Engineer Certificates.

I know little or nothing about the early history of either Engineer Rear Admiral Clarkson1 or of a later Engineer Rear Admiral McNeil2, but I feel that they were much in the same mould; strong willed, able and ready to take on all comers in pursuit of their objectives, and I believe they both roused antagonism because they nearly always won.

I had personal experience of Admiral Clarkson’s handling of differences with Board Members while I was Engineer Officer of Williamstown Naval Depot in 1920. Flinders Naval Depot was commissioned during this period, and as

1 Clarkson served an apprenticeship with Hawthorn Leslie and graduated as a naval architect and marine engineer. While in this role he worked in HMCS Protector and was offered the position of Assistant Engineer in this ship. This was in May 1884 when Clarkson was 25 years old and this brought him to Australia.

2 McNeil served in ships of the Union Steamship Company and Huddart Parker, joining the RAN in 1911 as an Engineer Lieutenant.

Engineer Officer of Williamstown Naval Depot I had some responsibility for the arrangements for the Engineering Branch at Flinders. Either the Gunnery or the Torpedo Branch (I think it was Gunnery) had jumped the claims of the Engineering Branch to two or three buildings which had been built for the Engineering Branch for the training of stokers, and had occupied these buildings.

I fell in before Clarkson with a protest, and soon a visit of the whole Naval Board was arranged to go into the matter on the spot. I was detailed to accompany Admiral Clarkson in his car, and to say my piece when called upon to do so. Clarkson backed me to the hilt, and won his case at every point, which caused the Second Naval Member, I think Captain Round-Turner, RN (Gunnery), to remark sourly that I had opposed him bitterly at every point. On our return to Navy Office (then located at Lonsdale Street in Melbourne), Clarkson smiled quietly and remarked to me, ‘Well Doyle, I think we gained our points’, or some such remark.

If I remember rightly, there was a sequel to this a year or two later when I was an assistant to the Engineer Manager, Starr, at Garden Island and when Round-Turner3 was detailed to enquire into the admin-istration at Garden Island. I may be wrong about this, but I think that his report raised the question of the appointment of a Civil Secretary to Garden Island to tighten up the administration of the civil staff there. Previously the secretarial side was done officially by the Naval Secretary to the Commodore Superintendent and much of it was really done by the Engineer Manager and his staff.

While the appointment of a Civil Secretary no doubt relieved the Engineer Manager of a good deal of administrative work, it also meant the addition of another head of a section to be dealt with while still leaving to the Engineer Manager the responsibility for getting the work done. The Civil Secretary was responsible to the Commodore Superintendent, not to the Engineer Manager.

I have noted the above happenings because I think they played their part in the downgrading of Senior Engineer Officer in the Dockyard from General Manager to Engineer Manager and in reducing the authority of the Engineer Manager over the Dockyard workforce. Having recorded this bit of background information I now come more closely to Garden Island.

Engineer Captain George Bromwich, RN, General Manager Garden Island

My main contact with Captain Bromwich was about 1917 when I was examined by him to qualify for promotion to Engineer Lieutenant Commander; I was then Senior Engineer of HMAS Encounter. He passed me and asked if I would like to be appointed to the Dockyard. I thanked him and said I wanted to stay at sea while the war lasted. He quite understood and did not pursue the matter.

I was told by RN Engineer Officers that his name was originally Cockey4 but a benefactress who was a relative left him a considerable sum of money on condition that he took her name ‘Bromwich’ and that he accepted the condition and changed his name by deed-poll. As far as I know Bromwich ran the yard satisfactorily and was generally well regarded. He was perhaps a little over conscious of his own dignity. What his relations with Clarkson were I do not know but at that time King-Salter5 was in the ascendant at Cockatoo Dockyard and

I suspect that Garden Island and Bromwich would have been in second place as far as Clarkson was concerned and Bromwich’s dignity would have been considerably ruffled.

If I remember rightly, King-Salter had a house on Cockatoo Island which was either built for him or extended for him and was quite a comfortable dwelling. Bromwich considered that he too rated a good house and applied for one to be built upon the Hill at Garden Island. I believe that plans were drawn for this house by the Works Department but construction was deferred.

When I became Engineer Manager in 1933 it was suggested to me that I should apply for this house to be built but I said ‘No, ‘Tresco’ is in danger of being lost by the Navy, others are after it and the Government would be only too glad to hand it over and if a decent house were built on the Hill for the Engineer Manager we would soon have the Admiral Superintendent living in it and the Engineer Manager back in his present cottage practically in the Superintendent’s backyard’.

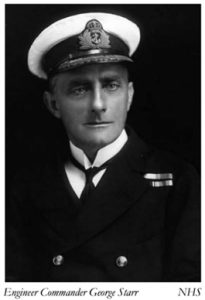

Engineer Commander George Starr, Engineer Manager Garden Island

Engineer Commander George Starr was Engineer Manager Garden Island when I became Second Assistant in 1921. I have a strong suspicion that the position was downgraded from General Manager to Engineer Manager for two reasons: the Naval Board’s experience with Clarkson as Third Naval Member and the objection of the other Board Members to having an Engineer Officer in such an influential position as a Member of the Board and the wish of the other Board Members to bring the Engineering Branch generally more into line with their counterparts in the Royal Navy, a move which was actually pursued when Clarkson was retired in October 1922.

The then First Naval Member, whose name I don’t remember (VADM Sir Allan Everett, RN was Chief of Naval Staff and First Naval Member from November 1921 to August 1923) announced, I was told, that he would take over the duties of the Third Naval Member in addition to his own and brought out from the Royal Navy an Engineer Lieutenant Commander and appointed him to his staff to do the routine work of administration of the Branch and had him appointed Director of Engineering. This Officer, Deacon6 by name, may have been a junior Engineer Commander but I don’t think so when he first arrived. He was certainly well junior to Starr.

I was told at the time that the Admiralty, a vague term which covers many people, had told the First NM to see that no more Engineer Officers were appointed to the Board. The First NM – Deacon set up carried on until with the building of HMA Ships Australia and Canberra in Britain, Engineer Captain Sydenham, RN7 was appointed Director of Engineering (Naval) and Deacon returned to the Royal Navy. Again, I was told that Sydenham was offered the position of Third NM after all but refused it because he felt that the Admiralty was against the idea on principle and he felt that acceptance might prejudice his own prospects of promotion. Naturally Starr was not very pleased with the First NM – Deacon set up while it lasted.

Reverting to the Naval Board – Clarkson relationship. It was a forerunner in many ways I think to the Naval Board – McNeil relationship when McNeil became Third Naval Member. Clarkson and McNeil were very strong personalities and had no hesitation in pushing their views regardless of persons.

Starr was an able man, good looking, with an attractive personality and a strong sense of humour. I feel sure that he would have been promoted in the RN, and gone further in the service if he could have restrained his sense of humour. I quote some examples of the latter:

When he was Gunmounting Officer at I think Portsmouth, an Admiralty Order was issued that certain guns at outlying ports were to be rendered unserviceable. Some Gunmounting Officer wrote in asking how this should be done. Starr’s official reply was ‘This is left to the discretion of the GM Officer concerned. Personally I always use the well-known Turkish Method – the removal of vital parts.’

While at Garden Island Starr frequently came up against Clarkson, then Third NM. Cockatoo Dockyard was in the ascendant and whenever Starr applied to Navy Board for approval to buy some piece of equipment for Garden Island the almost invariable reply was ‘Not Approved’, however good a case was put for buying it. Clarkson was awarded a CMG. Starr’s remark to me, then first Assistant, ‘CMG –very appropriate, Clarkson Must Go.’

The Minister for the Navy and the full Naval Board made a visitation to Garden Island and whilst walking around the Island accompanied by the Superintendent and the Engineer Manager, they came upon the spare 12-inch guns for the battle cruiser Australia deposited on the ground opposite the then boat steps near the old Barracks building. The Minister walked up to the guns and halted and the whole Naval Board including Clarkson and the Superintendent and Starr halted with him.

The Minister said, ‘Well well, I wonder what Nelson would have thought if he could have seen these guns?’ ‘I don’t know Sir’, replied Starr ‘but I can assure you that he would have been quite at home in our Machine Shop.’

At one stage, in the early twenties I think, there was an agitation to build a Main Naval Base (The Main Naval Base and Dockyard?) away from Sydney and positions proposed for it ranged from Darwin to the vicinity of Hobart. A parliamentary committee inspected the proposed locations and took evidence from interested parties.

Starr was called upon to give evidence and if I remember rightly was in favour of Port Stephens near Newcastle. The Navy had had a reserved area in Port Stephens since the receipt of the Report and Recommendations of Admiral Henderson, RN about 19038. Having heard Starr’s evidence, one of the Parliamentary Committee Members said, ‘Well Engineer Commander Starr, Engineer Rear Admiral Clarkson told us that in his opinion an area in the vicinity of Hobart Tasmania was far and away the best natural position for a main Naval Base in Australia, what have you to say to that?’ ‘I couldn’t agree more Sir,’ said Starr, ‘providing that you are expecting an attack from the South Pole’.

George Starr and Dan Craig

During WW I many Garden Island employees wished to volunteer for service with the Armed Forces but were dissuaded by the Management, being told that they were doing essential war work and must stay on in the Dockyard and that their doing so, despite their wish to volunteer for overseas service, would be recorded in their favour. So far as I know their assurances were verbal only. (Sorry Mr Whitlam, ‘oral’)

With the passing of the Returned Servicemen’s Preference Act and the ending of the war many returned men applied for work at Garden Island and got it, and displaced many employees who were not covered by the Act. One, Dan Craig, whose place was on our largest lathe in the Machine Shop, applied to Starr for some official assurance that he would not be discharged if some returned serviceman covered by the Preference Act applied for his job, and pointed out that he had wanted to enlist but was restrained from doing so by the management saying that he was doing essential war work and could not be spared, and that these facts would be noted on his records, and that his job would be safeguarded thereby.

Starr said ‘Right, we will ask Navy Office for an official assurance that as a Garden Island war worker you will not be discharged if some Returned man applies for a job’, and a letter to Navy Office was drafted accordingly. Predictably the application failed to get a satisfactory assurance.

Starr informed Craig and they decided to apply again and keep on applying till they got a satisfactory assurance and the correspondence grew into quite a file. Finally Starr, tongue-in-cheek, suggested that a special medal be struck for Garden Island war workers as permanent record that they had in fact been doing essential war work and were restrained from enlisting in the Armed Services. To Starr’s amazement the answer came back, ‘Approved, submit a suitable design’.

Starr took a silver coin, a half crown, had it ground smooth on both sides inside the milled edge which was retained, and on the obverse side silver-soldered a naval button. On the reverse side a suitable inscription was engraved saying that the medal was awarded to ——, Garden Island War Worker 1914 – 1918 to record that he had been doing essential war work during that period and restrained from enlisting. Also on the reverse side, just inside the milled edge of the coin and around the above mentioned inscription was engraved the Latin words: ‘ditera scripta manet’. The whole medal was silver plated and had quite an attractive appearance. The Commodore Superinten-dent, Edwards by name (CDRE Superintendent H.McI. Edwards, RN 1920 -1923) and very executive, approved the design generally but asked ‘What does this Latin inscription mean?’ ‘The written word remaineth’ said Starr. (More freely, If you’ve got it in writing you’re right). ‘Well I’m afraid we can’t have that’ said Edwards, ‘Make a similar medal but omit the Latin.’ In due course this was done; the medal was approved by Naval Board.

The whole Garden Island workforce was fallen in forming three sides of a hollow square outside the entrance door leading from the Dockyard to the Main Office Building and the Commodore Superintendent attended by his staff and the Heads of Dockyard Departments, made a speech and presented Dan Craig, Garden Island war worker, with his medal. A sequel to this incident came after Starr had retired to his farm in Sussex, England. He was visited by a famous numismatist who claimed to know the history of every medal struck in the British Empire or some such claim. Starr had kept the first medal with the Latin inscription and produced this and challenged the numismatist to tell him the history of that one, and the numismatist had to admit defeat.

Frank Nicoll

When I was first appointed to the Dockyard as Second Assistant we had, as far as I remember, a very small drawing office staff, in fact I remember only one Draftsman, Mr Rigby9 and no Ship Drawing Office, but during Starr’s time, Mr Frank Nicoll was appointed and became Hull Overseer and head of a Ship Drawing Office, a small temporary structure alongside the path leading up to the Hill, the first building to be passed on this path from the Dockyard flat area. This appointment created quite a trickish position. Hitherto the Engineer Manager had retained and automatically carried out much the same duties concerning the organisation and execution of the refits and dockings of naval ships as had been discharged by Bromwich as General Manager and no one had raised objections as far as I know.

Traditionally in RN Dockyards the Naval Construction Branch which dealt with the design, construction and refitting of ships’ hulls, was the Senior Branch. Would Nicoll’s appointment lead to the same organisation in Garden Island Dockyard as that in RN Yards? Starr did not raise the question, he simply assumed that the Hull Overseer and Ship Drawing Office Staff were part of the Engineer Manager’s Staff and acted accordingly and this arrangement was accepted loyally and so far as I know without protest by Frank Nicoll although the fact that Leask, the Head Naval Architect at Navy Office and his staff were under the Third Naval Member, an Engineer Officer, at Navy Office was always a sore point with Leask and some of his staff.

This reminds me that in McNeil’s time as Engineer Manager Garden Island, Herbert, then First Assistant, who had an orderly mind, suggested to McNeil that he (Herbert) should draw up a statement of ‘The Engineer Manager’s Duties and Responsibilities‘, as Herbert felt that the GM’s staff were doing a lot of things that were not really within their responsibility. McNeil replied much as follows, ‘If you do that Herbert, you will find that our responsibilities and with them our authority will become very small compared with what they are at present. We have acquired the standing that we now have by voluntarily assuming responsibilities that other branches have not bothered to discharge.’

To my mind Frank Nicoll did a tremendous job in his time at Garden Island. He built up the Ship Drawing Office from nothing to an efficient organisation and also began and led an efficient Hull Overseeing Staff. I had, and have, a great admiration and respect for him as a man.

Bob Hodson

Bob Hodson is another man who did a tremendous job. I am a little hazy now about the beginnings of the Garden Island Civil Electrical Staff and just when they took over from uniformed members of the Torpedo Branch.

As far as I remember, Bob Hodson, then a Torpedo Gunner in one of the cruisers up New Guinea way, blew his left forearm off when dynamiting fish for fresh food for the ship or for the mess during the latter part of WW I and was invalided out of the RAN, and appointed to Garden Island in charge of the Civil Electrical Staff. He was there when I joined the Dockyard in 1921.

He kept pace with electrical developments in the Navy, which were pretty primitive in 1921, until he retired from Naval Service. On several occasions Hodson asked for information from the Admiralty about rather specialised techniques and was told ‘You must send the job over here, we always send that work to the makers of the equipment’ and in due course he was able to say, ‘Thank you very much, we have done the job satisfactorily’. If I remember rightly, he introduced boats echo sounding equipment for our surveying ships’ boats before the Admiralty did for theirs.

When the Korean War was on, the automatically controlled AA guns of our Battle Class destroyers worked satisfac-torily. The RN destroyers reported that their similar guns were no use and the automatically controlled radar was unsatisfactory. This caused the RN Admiral to reply ‘Well those Australian destroyers’ similar guns work satisfactorily and yours had better or else’ or words to that effect. This result I believe was due to the fact that Hodson would not accept the assurance that the control equipment sent out with the guns, allegedly ready for installation immediately on receipt, was in fact ready and insisted on opening it up for examination and cleaning it all before installing it. No doubt our naval gunnery Staff on board were responsible for keeping the equipment efficient but I believe Hodson’s efficient installation was largely responsible for our success.

About the time I retired, or soon after, Hodson was sent over to England and had a run around Admiralty establishments, especially the electrical ones. When Admiral Charles Clark went over about the same time the head of the RN Electrical Branch, I forget his title, said to Charles Clark, ‘Wherever did you get that man Hodson from? I never met a man before who so quickly got such a comprehensive grasp of detail’, or some such remark. Bob Hodson too I feel, did a tremendous job for Garden Island and for the RAN.

Engineer Captain P.E. McNeil, Engineer Manager Garden Island

As far as I remember McNeil10 succeeded Starr as Engineer Manager Garden Island and General Overseer. I am now finding it hard to get happenings of that and later periods in the right chronological order and to separate things that happened at Garden Island when McNeil was Engineer Manager Garden Island and those that happened when he was Third NM. I have remarked earlier on McNeil’s personal characteristics. I think Frank Nicoll summed them up neatly when he said that he admired McNeil for his rugged character.

At one stage Defence generally was so depressed that Garden Island came very close to being shut down altogether as a naval refitting and repair yard and all naval refitting work being transferred to Cockatoo Dockyard. As I remember it, this fate seemed to be hovering over us several times in the 1920s and early 1930s. Anyway, either Mr Farquhar,12 then Chairman of the Shipbuilding Board which was running Cockatoo Island in the early and mid 1920s or Mr Fraser, Managing Director of the Cockatoo Docks and Engineering Company which took over Cockatoo Dockyard in the late 1920s, said to me, ‘You can thank that McNeil for saving Garden Island, I actually had the authority in my pocket for taking over the work, which would have meant closing down Garden Island as a repair and refit yard, but McNeil put up such a battle that we did not go on with it.’

You will have access to the archives and be better informed than I am, but from memory I think that at one stage, maybe when Moresby was being converted from coal to oil burning, Garden Island got down to a little over 300 workshop staff.12 As things turned out, it was indeed fortunate that McNeil saved the day for Garden Island. McNeil had a gift for producing striking phrases on occasion. About this time in naval affairs there was a strike at Cockatoo, McNeil’s comment to me, ‘Doyle, unless our people learn that work is a privilege and not a punishment, Australia will never prosper as she should.’ He certainly lived up to his expressed standards. He did a tremendous job for Australia in WW II and hastened his own death thereby.

A.B. Doyle, Engineer Manager and General Overseer

I was fortunate indeed in the team we had at Garden Island in my term as General Manager (sic) and General Overseer, Naval Assistants including from time to time such people as G.I.D. Hutcheson, Arthur Mears, Charles Clark, Ken Urquhart, John Bull, O.F. McMahon, Roger Parker, Tom Clift, and on the civil side Frank Nicoll and Bob Hodson in the Hull and Electrical Section and Douglas Apsey, the Engineer Manager’s Secretary. The Naval Assistants mentioned are too well known to need any comment from me, Frank Nicoll and Bob Hodson I have already written about.

Douglas Apsey, Engineer Manager’s Secretary

As well as being a very efficient secretary, he was extraordinarily know-ledgeable about key men and issues in the Dockyard Workforce and was well balanced and sensible in his outlook.

Willie

I must not forget Willie, quite a personality and principal messenger on the Engineer Manager’s Staff. Willie was an ex-Marine and had the characteristics of the traditional old soldier. Whilst doing his duties, as he conceived them, efficiently, he also guarded jealously his privileges as the Engineer Manager’s Messenger, also as he conceived them. In person he was lean and dark with a thin and drooping moustache and a rather saturnine expression.

One particular habit of his impressed itself on my memory, Willie bringing the Engineer Manager’s mail, both official and private, to me in the office. Any letter that looked interesting he would, quite openly and before he handed it to me, hold it up to the light to see if he could read any of the contents and if possible hazard a guess as to whom it came from and what it was about. On one occasion as he held a letter up to the light he said to me, ‘This letter is to Mrs Doyle, it is in a man’s handwriting, would you like to open it and read it before I take it up to Mrs Doyle at the house?’ Quite entertaining really even if not conscious of being so and how welcome a little comic relief was.

Workforce Numbers

If I remember rightly, in my time as Engineer Manager and General Overseer, the Garden Island workforce increased from 500 or so to about 2,700 and the composition of the workforce changed from about 90% ex-servicemen to include a considerable number of radicals and stirrers who were not ex-servicemen. Naval officers on the Dockyard and Overseeing Staff for whose work the Engineer Manager and General Overseer had some responsibility increased from three or four to around 60 or 70. Some new sections such as the Degaussing and Radar Sections worked officially under direction from Navy Office, the EM and GO shared in the responsibility on an ill-defined basis. This factual division of responsibility occurred also to some extent in sections of contract work. However, on the whole we got by satisfactorily; we all had the same end in view and worked together.

Engineer Captain G I D Hutcheson, Engineer Manager and General Overseer Garden Island

Engineer Captain Hutcheson relieved me as Engineer Manager and General Overseer in September 1942, in time to see to the completion of the Captain Cook Dock and to service the British Pacific Fleet. A most able man himself, he had the advantage of Deputy Engineer Manager, Frank McMahon, to relieve him of much routine work, especially paperwork, which previously had to be done personally by the Engineer Manager.

This was something that I had asked for, for myself, stating that this routine and paperwork took up so much of the Engineer Manager’s time that, despite long hours, he had insufficient time to think and plan ahead. My request was refused on the score that no suitable person was available. With the sinking of Canberra, one became available.

The RAN was most fortunate in having a man of Hutcheson’s ability and energy as Engineer Manager and General Overseer at the time when he was most needed and the reputation of Garden Island Dockyard became high within ships of the BPF. I understand that the Admiral Commanding BPF in Sydney (Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser) thought so highly of it that he sent a signal to the Admiralty commending to the attention of Their Lordships the organisation of Garden Island management, in which responsibility for the repair and refit and docking of ships was discharged by one Technical Head.13

A.B. Doyle, Third Naval Member and Chief of Construction

I was appointed to this position on 25 September 1948 after a bare twelve months as Director of Engineering (Naval) at Navy Office, my first appointment to Navy Office and hardly long enough to get acquainted with the inner workings of Navy Office. A period there as a junior officer would have been of great help to me both as Engineer Manager Garden Island and in my two appointments at Navy Office in senior positions.

The two main matters in my term as Third NM that concerned Garden Island arose from my mission to Britain in 1944 to arrange with the Admiralty a building programme for the RAN. First was the proposal to get (E) Officers from within our own Engineering and Construction Branch trained to be also Constructors by the Royal Corps of Naval Constructors.

We had reason to believe that the Royal Corps were urging the appointment of a Member of their Corps to head the Construction and Ship Drawing Office Staff of the RAN, and we had good reason to oppose this move:

- Traditionally the Construction Branch was the senior technical branch in the RN, and the appointment of an Admiralty Constructor on loan to the RAN would almost certainly lead to the establishment of a separate, and Senior, Construction Branch in the RAN.

- The RAN is a comparatively small organisation and offers limited career opportunities for Naval (E) Officers. We really neither needed nor could afford a separate Branch of Constructors.

- Our (E) Officers, selected ones, could, if the Royal Corps would help us, successfully combine training for both Engineering and Construction duties in the RAN and, again if the Royal Corps were willing, for any exceptional requirement we could continue to ask the help of the whole RN Corps.

We feared also that for such a small service as the RAN was at that time, a really first class RN Constructor would be unwilling to volunteer for fear of prejudicing his career prospects. Just before he retired Admiral McNeil prepared a proposal to put before the Admiralty under which suitable ‘E’ Officers from the ‘E’ training course in Britain would be selected to undergo the course for Naval Constructors thus qualifying for both Engineering and Constructor’s duties. These Officers would naturally have an excellent chance to be appointed to senior positions in the RAN Engineering and Construction Branch and would be well qualified for employment in civil occupations after retiring and we hoped that these better prospects would encourage them to remain in the RAN service as long as they were required.

I inherited the task of getting the Admiralty and the Royal Corps to agree to this plan and it was my first effort in my mission to the Admiralty to try and pilot it through. The position was rather ticklish, as shortly before he retired McNeil had rather ruffled the DNC’s feelings by telling him that we did not need his advice about whether or not we should remove the after turret from Australia and in fact we had retained it whilst, on his advice, RN ships had removed it or were doing so. In fact, I was put on the mat about this by the Deputy Controller as an opening gambit of our conference with the Controller and certain of his staff officers and later by the DNC.

However, the plan was finally accepted and two (E) Officers of the RAN completed the Constructors’ Course. Regrettably the after-war slump in RAN construction and prospects generally caused one of them to retire from the RAN fairly soon, what happened to the other one I do not know15 nor do I know whether any more (E) Officers have qualified as constructors.

The second proposal arose from my visit to USN Dockyard in United States and Hawaii, in which I found the USN organisation to be rather like our General Manager concept under which one Technical Officer, in our case the General Manager, ran the whole yard but the USN General Manager had a wider authority than ours, more like that of the Admiral Superintendent. I put my proposals on paper with reasoned arguments in favour of them and presented them to the then First Naval Member, Sir Louis Hamilton. Sir Louis had a talk to me about them but in conclusion simply said that if in fact my proposed organisation was better than that in the RN Dockyards, the Admiralty would have already adopted it. They had not and therefore it was not better and that was that as far as he was concerned.

A few months later, when Hamilton had left us, I put it to Sir John Collins soon after he became First Naval Member. When I first put it to him, Sir John said ‘No’, but a little later on he said to me that on reflection he thought I had made my point and that if the Admiral Commanding the Eastern Area, the Admiral Superintendent15 raised no objection, he, Collins, would agree to the proposed reorganisation. I asked Collins if he had any objection to my taking the plan and presenting it personally to the Admiral Superintendent, explaining my reasons to him and stating that Collins would agree to it provided that the Superintendent, George Moore at that time, had no objection. Collins agreed and I did so, but George Moore consulted his Master Attendant (LCDR R.H. Kerruish, RAN) who predictably objected. ‘Give me the Authority and I will run the Dockyard’, and George Moore refused to agree.

I think Charles Clark revived the plan when he became Third Naval Member, finally for what reason I do not know. Weymouth, then I think Director of Shipbuilding in the Shipping, or Shipbuilding, Board was appointed to investigate the Naval Dockyard organisation at Garden Island, and Weymouth16 came up with the present arrangement, a Naval Officer of the Engineering and Construction Branch as General Manager, but with a less general authority than my proposal would have given him.

That proposal brings my service in the RAN to an end. I have written these things down as I doubt if much of them is known to anyone else now alive, unless it be Mr Apsey and I felt that they might be interesting to anyone concerned with history of the early days of the RAN and of Garden Island Dockyard.

Alec B Doyle

15 April 1979

Footnotes:

1 Clarkson served an apprenticeship with Hawthorn Leslie and graduated as a naval architect and marine engineer. While in this role he worked in HMCS Protector and was offered the position of Assistant Engineer in this ship. This was in May 1884 when Clarkson was 25 years old and this brought him to Australia.

2 McNeil served in ships of the Union Steamship Company and Huddart Parker, joining the RAN in 1911 as an Engineer Lieutenant.

3 A Royal Commission was held from April to June 1921 to enquire into shipbuilding and ship repairing as well as the operations of Cockatoo Island and Garden Island Naval Dockyards. Captain Charles Wolfran Round-Turner, RN had been appointed for duty at Navy Office in July 1920. His enquiry into the administration of Garden Island may have been related to the Royal Commission but played no part in the downgrading of the position of General Manager to Engineer Manager as Cmdr Starr had been appointed as Engineer Manager on 1 May 1920, before any of these events.

4 The first reference to the appointment of this officer to HM Naval Establishment Garden Island was in the name of Cockey. He was engineer officer of HMS Centurion and landed with the Naval Brigade for the defence of Tientsin. He was awarded the DSO and was Mentioned in Despatches for his services in China. After return to the Royal Navy he was promoted to Engineer Rear Admiral.

5 John J King-Salter, a member of the Royal Corps of Naval Constructors was Assistant Constructive Manager at Chatham Dockyard when the Commonwealth took over the NSW Government Dockyard Cockatoo Island in 1913. That year he was loaned and appointed General Manager at Cockatoo. He was under the administrative control of Captain Charles F. Henderson, RN who was Chief Engineer of Garden Island Dockyard – which remained under RN control until 13 October 1913.

6 Engineer LCDR John L. Deacon, RN who served at Navy Officer and returned to RN service in October 1923.

7 In October 1923 Engineer CAPT E.D. Sydenham, RN was listed as adviser and naval assistant to the Board and Director of Engineering. There was no Third Naval Member at this time.

8 Admiral Sir Reginald Henderson’s Report is dated 1 March 1911.

9 The sole draughtsman was Mr Douglas Williamson who preceded Mr W G Rigby.

10 Engineer Captain Percival Edwin McNeil was Engineer Manager of Garden Island from 1922 to 1928. Later as Rear Admiral he became Director of Engineering RAN and Third Naval Member, he was Director of the Shipbuilding Board from 1943 to 1948.

11 Robert Farquhar was Chairman of the Commonwealth Shipping Board and Director of Commonwealth Shipbuilding controlling the Cockatoo Island Dockyard from 1921 to 1929.

12 HMAS Moresby was converted from coal to oil burning in 1935. From a wartime peak of over 3,000 the workforce numbers had fallen to 1,407 by 1920 and a mere 382 by 1931.

13 A story is told that when Engineer Captain Hutcheson was showing Admiral Fraser around the Dockyard, the Admiral asked ‘How many men work here Captain?’ to which Hutcheson is alleged to have replied ‘About 10% Sir’. This may just be another story as Hutcheson was very fond of the Dockyard and the workers of him.

14 Lieutenant (E) John F. Bell, RAN and Lieutenant (E) Ian Johns, RAN. It was the latter who retired. Captain John Bell was to become a General Manager of Garden Island Dockyard.

15 The title was in transition at this time (1948) and became Flag Officer in Charge NSW and Admiral Superintendent and Sea Transport Officer – Sydney. The occupant was Acting RADM George Moore, RAN.

16 Mr H P Weymouth was Chairman of the Australian Shipbuilding Board from 1945 to 1964. As a result of the Weymouth Plan the command structure of the Dockyard remained very much as the Royal Navy originated it in the 1890s with the General Manager being directly responsible to the Flag Officer Commanding East Australian Area.