- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Early warships

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2020 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By John McGrath

The refrain of Heart of Oak (yes, it is Heart not Hearts) are our ships, begins: ‘Heart of oak are our ships, jolly tars are our men’. These words have been sung with gusto by generations of RN officers both serving and retired, perhaps most memorably at the annual Trafalgar Night dinners. With words by David Garrick (1717 – 1779) and music by William Boyce (1711 – 1779), it had its first public performance at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, on New Year’s Eve 1760 in the pantomime Harlequin’s Invasion. Although replaced in the Royal Australian Navy by the march Royal Australian Navy, it remains the quick march of the Royal Navy, the Royal Canadian Navy and the Royal New Zealand Navy.

The ‘wonderful year’ of the first verse was 1759, during which Britain won many important battles including the great naval victory of Quiberon Bay (20 November). The British fleet at this battle was commanded by Admiral Hawke flying his flag in HMS Royal George. With the major construction material for ships being oak and with the heartwood being the strongest part, this image reflects the solidarity of the wooden walls on which the security of Britain rested. Was this portrayal fully justified?

The Royal George, the most powerful warship in the world when she was launched in 1756, was still an impressive ship in 1782 when she still carried 104 guns. Wearing the flag of Rear-Admiral Richard Kempenfelt, she was anchored at Spithead and in the final stages of preparation to leave as part of Admiral Richard Howe’s fleet bound for Gibraltar to deliver relief to the besieged garrison. On 29 August, the ship was careened to port to repair a defective drain from a water tank. Most of the crew of 865 were on board, the major exception being 60 Royal Marines landed that morning. Admiral Kempenfelt was in his cabin writing. In addition to the naval personnel, there were several hundred families and friends of officers and ratings come to say good-bye, one or two hundred ‘Ladies from Portsmouth Point’, many traders trying to secure last minute business and numerous dockyard workers busy with last minute jobs. Altogether there were in excess of 1,200, possibly as many as 1,500 people on board when at about 0930 she gave a sudden lurch to port and sank like a stone. The speed of her sinking can be gauged by the fact that only 255 of all those people were rescued.

Admiral Kempenfelt died in his cabin. That figure is shocking given that it happened in sight of shore in summer weather and in an anchorage crowded with ships and busy boats from the ships and the shore.

The Court Martial of the Captain and other survivors was held eleven days later and honourably acquitted them all because they were persuaded that the ship had not been over-heeled, was rotten through and through and had suffered a major structural failure brought on by the stresses from the careening. So, perhaps, not all ships were as well found as the words of the song suggest.

But what about those ‘jolly tars’? It all sounds very happy but even in the first verse, there is a clue that all might not be exactly as portrayed in those words: ‘To honour we call you, not press you like slaves’. At times of major conflict at sea, there was always a shortage of men to crew the large number of warships in commission, see Table A. These numbers, taken either side of and during the war in which the Battle of Quiberon Bay was fought, illustrate this point clearly. One solution to this was impressment (the press gang). This procedure started in 1664 and continued until after the defeat of Napoleon when a sharp reduction in the size of the Royal Navy led to a review of naval manning methods and the abolition of impressment.

| Dates | Activity | RN Manpower |

| 1753 – 55 | Peace | 17,369 |

| 1756 – 63 | The Seven Years’ War | 74,771 |

| 1773 – 75 | Peace | 18,540 |

Table A. The peacetime and wartime manpower demands of the Royal Navy1.

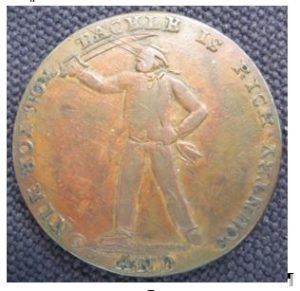

But there are other indicators of the problems faced by ratings that could cause resentment and unhappiness. Towards the end of the eighteenth century there was an acute shortage of small change in circulation. To solve this problem and keep businesses running, traders, campaigning groups and private individuals issued halfpenny tokens that were used as a substitute for official coinage. Among these is the ‘Tom Tackle’ token issued in Middlesex by an unknown person.

The name Tom Tackle is similar to Jack Tar, used to refer to a generic sailor. In the obverse view Tom is shown fit, strong, brandishing a cutlass and ready for a fight. He is clearly a happy man. Around the upper part of the circumference, the legend reads:

TOM TACKLE IS RICH; perhaps he has collected prize money as well as his pay. Around the lower part is written: FOR KING AND COUNTRY.

The story told on the reverse is completely different. Here Tom’s left leg is wooden, he supports himself on a crutch and is holding out his hat; he has become a beggar. The corresponding legends read: TOM TACKLE IS POOR and MY COUNTRY SERVED. This is a clear attack on the treatment of unwanted sailors who, unless they were lucky enough

to get a berth in the Royal Naval Hospital, Greenwich, were discharged onshore with no provision for their future well-being.

The composer and author Charles Dibdin (1745 – 1814) is probably best known today for the sea-song Tom Bowling, so often played at the Last Night of the Proms, but that was only one of many that he wrote and the themes of this token are taken from another of these songs, The Ballad of Tom Tackle:

Tom Tackle was noble, was true to his word;

If merit bought titles, Tom might be my lord;

How gaily his bark through Life’s ocean would sail

Truth furnished the riggings and Honour the gale;

Yet Tom had a failing if ever man had,

That, good as he was, made him all that was bad;

He was paltry and pitiful, scurvy and mean,

And the snivellingest scoundrel that ever was seen:

So said the girls and the landlords longshore,

Would you know what his fault was? – Tom Tackle was poor.

‘Twas once on a time when we took a galloon,

And the crew touch’d the agent for cash to some tune,

Tom a trip took to jail, an old messmate to free,

And four thankful prattlers soon sat on his knee.

Then Tom was an angel, downright from heaven sent!

While they’d thanks be his goodness should never repent:

Return’d from next voyage he bemoan’d his sad case,

To find his dear friend shut the door in his face!

Why d’ye wonder? Cried one, you’re served right, to be sure;

Once Tom Tackle was rich — now Tom Tackle is poor!

I bain’t, you see, versed in high maxims and sich;

But don’t this same honour concern poor and rich?

If it don’t come from good hearts, I can’t see where from,

And dam’me, if e’er tar had a good heart ’twas Tom.

Yet somehow or ‘nother, Tom never did right:

None knew better the time when to spare or to fight:

He, by finding a leak, once preserved crew and ship.

Saved the commodore’s life — then he made such rare flip

And yet for all this, no one Tom could endure;

I fancies as how ’twas — because he was poor.

At last an old shipmate, that Tom might hail land.

Who saw that his heart sail’d too fast for his hand.

In the riding of comfort a mooring to find.

Reef ‘d the sails of Tom’s fortune, that shook in the wind:

He gave him enough through Life’s ocean to steer.

Be the breeze what it might, steady, thus, or no near;

His pittance is daily, and yet Tom imparts

What he can to his friends – and may all honest hearts,

Like Tom Tackle, have what keeps the wolf from the door,

Just enough to be generous — too much to be poor.

This clearly suggests that all was not as rosy as portrayed in the words of Heart of Oak and further, undeniable evidence came in 1797 with the naval mutinies at the fleet anchorages of the Nore and Spithead. These drew public attention to the problems of pay and conditions as they affected the men on the lower deck and resulted in the first tentative moves towards very necessary improvements.

Next time that you hear or sing this famous sea-song, please dwell for a moment on the real state of those ships and the lives of those tars.

Notes:

1 Slight, Henry, True Stories of H.M. Ship Royal George from 1746 to 1841 (Ryde: E. Hartnall, 1841)

2 Fischer, Lewis R. & Nordvik, Helge W. Shipping and Trade, 1750-1950: Essays in International Maritime Economic History 1990, p. 2