- Author

- Date, John C., RANVR (Rtd)

- Subjects

- History - WW1

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 1993 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Whilst the tumult and the shouting was continuing over the debacle, or otherwise, of the great Battle of Jutland (31st May, 1916), the British Secretary of War, Field Marshall Horatio Herbert, Earl Kitchener of Khartoum was to be lost in the sinking of the armoured British cruiser H.M.S. HAMPSHIRE off the Orkney Islands north of Scotland on 5th June, 1916 shocking the British people and indeed the world.

Devonshire Class Cruisers: Devonshire, Hampshire, Argyll, Roxburgh, Antrim, Carnarvon.

| Displacement: | 10,850 tons |

| Length: | 475 feet |

| Power: | 21,000hp – 2 shafts |

| Propulsion: | 2×4 cylinder, Triple Expansion Steam Engines |

| Speed: | 23.47K |

| Crew: | 655-700 |

| Armament: | 4×7.5 inch 6×6 inch 2×12 pounder 22×3 pounder 2×18 in Torpedo Tubes |

With the loss of 656 of HAMPSHIRE’s ship’s company, only 12 crew surviving, together with the General and his cortege, made it a major naval tragedy. However, it was also to become one of the world’s most intriguing mysteries induced by several unusual factors, namely,

(1) that Lord Kitchener had even contemplated leaving the British Isles;

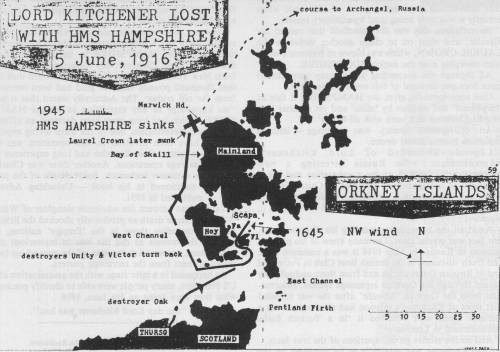

(2) that the cruiser HAMPSHIRE was at the time navigating the uncommon channel west of the Orkney Islands, when heading for the Russian northern port of Archangel;

(3) that the explosion that sank the ship may have been by a mine, a torpedo or by sabotage; and

(4) that the lack of an immediate official press release, understandably necessary for wartime security reasons, raised doubts as to the correct saga of events.

HAMPSHIRE’S loss was not convincingly explained after it went to the bottom to join many less famous wrecks in that area, including three longships laden with gold and treasure sent by Macbeth, High King of Scotland, made famous by Shakespeare’s play, to his cousin. He was Thorfinn Skullcrusher, Jarl of the Orkneys, and the gesture was in gratitude for help against Macbeth’s enemy, Duncan. Unfortunately, before the treasure ships reached the islands, a storm arose and all ships were lost.

The tragic affair with the HAMPSHIRE evolved early in 1916 with Lord Kitchener’s decision to personally visit Russia to discuss the supply of munitions and other details with the Russian Government, a move approved by the British Cabinet.

On the fateful day of 5th June, 1916, Lord Kitchener, with his close friend Colonel Fitzgerald, interpreter Second Lieutenant R.D. MacPherson of the Cameron Highlanders, and staff arrived at Thurso on the northern tip of Scotland during the morning and there embarked in the destroyer OAK to be taken across the Pentland Firth to Scapa, and here he went on board the battleship IRON DUKE to lunch with Admiral of the Fleet, Sir John Jellicoe.

The weather at this time was very bad, and gradually became worse; blowing a heavy gale from the north-east, later shifting to the north-west and Admiral Jellicoe suggested postponing the trip until the weather had moderated. However, Lord Kitchener was insistent to sail at once, to maintain his schedule, since he had allotted only three weeks for the whole time of his mission.

After much discussion, Admiral Jellicoe gave Captain Herbert Savill of HAMPSHIRE his sailing orders which was to keep 1 to 1½ miles off the western shore of Hoy Island.

The reasons therefore for finally selecting this particular route were:

(a) With a NE wind there would be less sea and therefore more chance of the accompanying destroyers being able to keep up with the HAMPSHIRE.

(b) It was practically impossible for the route to have been mined by a surface mine-layer, owing to the long hours of day-light and the supervision kept over the Channel.

(c) Up to this date no minelaying by submarines had taken place farther north than the Tyne, presumably owing to their small radius of action.

At 1600 hours, Lord Kitchener and his staff proceeded on board the HAMPSHIRE, which slipped her buoy at 1645. Soon the HAMPSHIRE, in meeting heavy weather had to reduce her speed to 15 knots. At 1820, the two destroyers UNITY and VICTOR could not make more than 10 knots headway, so Captain Savill signalled them to return to their base, a perfectly sound procedure, since the destroyers were intended merely as a guard against submarine attack, and no submarine could have attacked in the gale that was raging.