- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2022 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Kate Reid-Smith

By the end of 1943, Japan’s archipelagic defensive perimeter across the Dutch East Indies was fracturing. Ongoing and successful Allied counteroffensives, on islands closest to the Australian mainland including Timor, were beginning to take their toll. It was an increasing problem for Japan’s military planners, especially when the Dutch West Timor capital of Kupang remained homebase to some of the Rising Sun’s most elite intelligence units. Here, various special operations organisations including the dreaded Kempeitai (Military Police Corps), Tokkeitai (Naval Secret Police), or various Kikan (combined Military Intelligence) agencies, vied for Tokyo’s attention. In Kupang, the head of one notable Kikan was career Japanese military intelligence officer, Captain Masanobu (Masayoshi) Yamamoto.

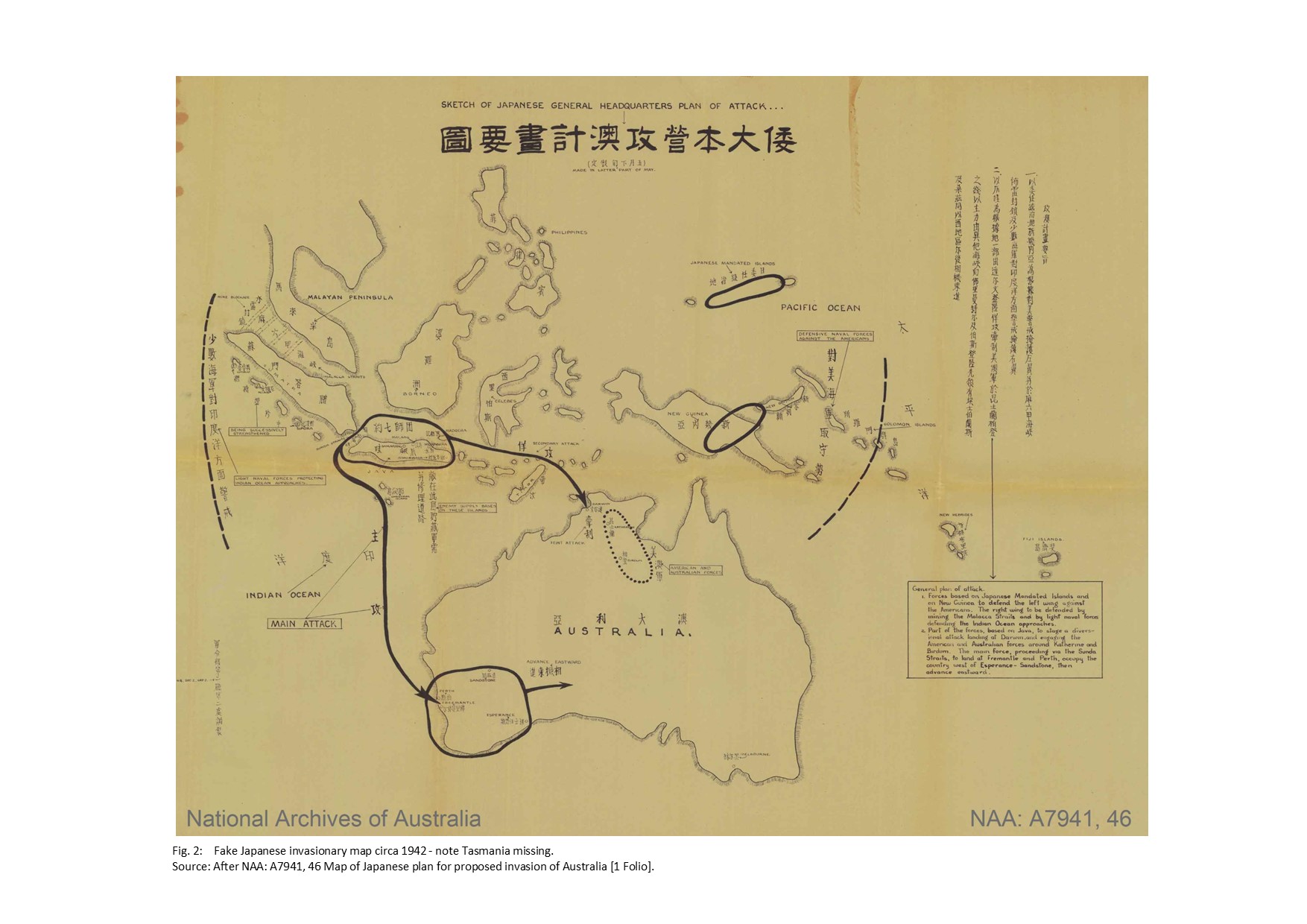

In Australia, the close proximity of the dreaded ‘Yellow Peril’ in Timor, was a cause célèbre for the general public. Singapore, the Dutch East Indies and New Guinea had already fallen, and all of Australia’s security hopes premised upon Britain’s Fortress Singapore ideology had collapsed. Japan’s threatened military encroachment closer to Australia hinted at some type of potential invasion of the northernmost frontiers. A threat perception encouraged by sensationalised media reports, and supported by government rhetoric, remained at the forefront of the collective national psyche. Even a fake map was introduced to the public, warning of Japan’s looming southwards thrust into Australia.

With Japanese forces seemingly inching ever closer to Australian shores, it seemed the country was facing a new self-defence realisation. Britain was preoccupied with its own self-defence on the other side of the world. The Americans were preoccupied with eastward island-hopping campaigns focused on recapturing the Philippines. It seemed as if Australia’s northernmost approaches had been marginalised. A sobering realisation, that perhaps the country now faced the very real prospect of going it alone.

Matsu Kikan Intelligence Operations

Almost 832 km north of Darwin, Yamamoto’s Matsu (Pine Tree) Kikan Unit went about its daily routine. They were named Matsu because pine trees symbolised longevity in Japanese culture. It was a small, well-trained joint Army-Navy group, operating as a force multiplier specialising in localised reconnaissance. Controlled administratively by the Ambon-based Japanese Second Area Army, their parent unit ran out of the Tokyo-based Second Bureau Headquarters. Considered a reserve and garrison force, the Second Area Army lay close to the bottom of Japan’s operational pecking order. On the other hand, the Second Bureau headquartered Army, Navy and Foreign Intelligence units were given priority.

Yamamoto’s four-member unit consisted of himself, along with two fellow battle-hardened veterans from the Sino-Japanese War. Like Yamamoto, Lieutenant Suzuhiko Mizuno and Sergeant Shinobu Furuhashi had cut their special operations teeth in China. All three were graduates of Japan’s benign sounding ‘Training Centre for Rear Duties Personnel’, the cover name for Japan’s Nakano School of Intelligence. This was the premier institution that transformed elite military intelligence officers into highly trained special intelligence operatives. The fourth member was wireless operator Lance Corporal Kazuo Ito, a fresh arrival from the Taiwan battlefront.

With Allied focus distracted elsewhere, by end of 1943 Kupang was a perfect place for Yamamoto’s Unit to operate. From here, he could mount covert field intelligence operations anywhere along what Japan considered was its southern-most wartime frontier. Despite ongoing Allied bombings, Kupang’s airfield and seaplane base were still staging platforms for ongoing Japanese incursions into the Dutch East Indies, New Guinea, Western Pacific and elsewhere.

Invasion: Reality or Idealised Possibility?

Timor’s proximity remained a problematic issue for Australia’s government. The entire archipelago was still considered the regional buffer zone between the mainland and Japan. It was part of the logic behind why several joint Australian-Dutch covert missions were deployed – unsuccessfully – into Timor throughout 1943. Their general mission focus was information gathering about Japanese air warfare, or any other near capabilities to Australia.

On the other hand, Tokyo was fairly confident in its detailed knowledge of strengths and locations of Australian-based air warfare. Equipped with a rudimentary working knowledge of some of the military capabilities stretching from Port Hedland to Exmouth, it was the potentially unknown ones from northern West Australia to the Northern Territory that really alarmed Japan. There was a growing uncertainty fueled by rumours of a large-scale American forward air-basing capability being planned for the area. This meant any enhanced Allied long-range bomber capability directly threatened not only archipelagic occupied areas, but perhaps even further afield into Malaya and beyond.

Western Australia’s Kimberley coastline was closest to the occupied Netherlands East Indies. Far Northern Queensland was closest to occupied New Guinea and Western Pacific, physical proximities that had not gone entirely unnoticed by Tokyo since at least early 1942. In Japan’s Indonesian Bandung Prisoner of War (POW) camp for example, Australian military personnel from northernmost Queensland and Western Australia were routinely isolated and interrogated. Queenslanders were questioned about areas in and around Cairns or Townsville. Western Australians were quizzed more in depth about what types of roads, beaches, aerodromes, power stations, hydroelectric works, military fortifications and so on, might be found anywhere from Derby to Darwin.

Australian planners already recognised that parts of northern Western Australia, including the Kimberleys, were vulnerable defence areas. So too did their Japanese counterparts. Tokyo had noted the region’s extreme isolation from major population centres, complete absence of infrastructure, and total lack of readily exploitable resources including fresh water. This meant while it was practically incapable of mounting any substantial anti-Japanese counter-offensive, it was also completely useless in supporting any potential Japanese occupation. By end of 1943, leading Japanese strategists had already dismissed outright, any potential north Western Australian invasion as futile.

Already knowledgeable about the remote Drysdale Airfield landing strip, refuelling and ammunition limitations, and without any immediate long-range threat, any planned invasion was off the table. On the other hand, increased long-range bomber capability directly threatened Japan’s entire southern defence perimeter. With an absence of any hard in-country intelligence on the matter, some sort of Japanese scouting mission was needed. In January 1944, that tasking fell to Yamamoto’s Kupang-based Matsu Kikan Unit.

Yamamoto’s Reconnoitrers Assembled

The route was plotted using captured Allied charts and Japanese pearling maps. The sailing route was south across the Timor Sea, towards the rocky coral outcrop of East Island (Ashmore Reef), and then on to Browse Island for initial observations. Landfall in Australia was to be made a day or so later, directly south as the crow flies from Kupang. The team were to visually record everything they saw using eight-millimetre film and newsreel cameras. But this was an area larger than the whole of Japan, and wherever the Allies might be building a new base within this vast 425,000km2expanse was like looking for a needle in a haystack.

Their mission was fraught with potential dangers. Not only were they to openly follow the routine Darwin-based bomber flypaths, but they were also to sail within sea lanes known for active anti-Japanese hunting patrols. Some air cover was to be provided as far as Browse Island, after that they were on their own. From here on they risked running into Japanese sea mines, or misidentification by Japanese submarines. They also risked sightings by Coastwatchers or Royal Australian Navy (RAN) intercepts. Yamamoto hoped to address both by carrying an Australian flag, and using a vessel camouflaged and crewed as a Timorese fishing boat. A sound reasoning, given that a plethora of non-Australian fishing vessels, were still operating in and around Australian waters at the time.

The vessel tasked may have been the Hiyoshi Maru Go 2, smallest of Japan’s three Hiyoshi Maru namesakes. A former civilian coastal carrier requisitioned in December 1941 and converted into an auxiliary gunboat, it had been retrofitted with machine and anti-submarine guns. Since early 1942, it had been under command of Lieutenant Tazaki Sueo, a highly experienced small boat officer. He and this vessel had already been involved in a variety of Japanese special operations, mostly in and around the easternmost fringes of the Dutch East Indies.

Around 17 January 1944, Yamamoto assembled his team onboard the Hiyoshi Maru moored in Kupang Harbour. Aside from his fellow Nakano graduates and the wireless operator, a further six enlisted and highly experienced Okinawan sailors formed the crew. Ten locally recruited teenaged Timorese males made up the boat’s complement. Crew confidence in surviving let alone reaching Australia undetected was not high, and a sense of foreboding was compounded by an adverse start. Within hours of sailing on the morning tides, the Hiyoshi Maru was rebuffed by monsoonal weather and forced back to port.

Two days later they sailed again, this time successfully reaching their first destination at East Island by late afternoon. Mooring close inshore, the group swam through the reef, filming themselves and the environs as they went. With nothing else to see other than blue sky, seabirds and guano, they sailed on to nearby uninhabited Browse Island. Here they found derelict remnants of an old structure, which the group decided was either an abandoned Australian outpost, or an old fishing camp. All agreed it was not military. With nothing of interest found, they set sail for their final destination, roughly 180 km southwards to Australia.

On 20 January the Hiyoshi Maru arrived near the entrance to Moran River, an area today closer to the Prince Regent River entrance into the Kimberleys. It was here they hid the boat in mangroves, before both scouting teams set out. What immediately greeted them, aside from sandflies and mosquitos, was the desolation of the place. Over the next two days they recorded vegetation, hill heights and mountain distances, beach depths, coastline compositions and so on. Aside from the natural landscape, there was no evidence of military, let alone any other development, anywhere. Mission accomplished, within forty-eight hours, Yamamoto’s team were back on board returning to Kupang.

Yamamoto’s Mission: Failure or Success?

This vast nothingness was a void Yamamoto emphasised in his post-deployment reporting. Despite all of them being out in the open, none of them had been interfered with or disturbed in any way. They had neither seen nor heard any planes, vehicles, vessels, animals, birds or any other human beings for that matter. There was nothing in this rough, stony, desert terrain of any practical use to Japan’s war effort, nor anything posing any type of potential threat. Yamamoto’s report however, may have been very different if they had landed some 160 or so km further northwards closer to the Anjo Peninsula.

Japan’s Kimberley focus may have tied in with pre-existing Japanese intelligence of Drysdale, which was not capable of sustained large-scale long-range bomber actions. If Japan had learned a long-range airfield was being built somewhere in the region, then strategic logic may have dictated the intelligence was probably sound. The reasoning was that by January 1944, Japan’s hierarchy were acutely aware that the tide of war was turning. With Australian-based shortfalls in long-range counteroffensive capabilities, it was a practical assumption that some type of long-range capacity might be developed. That Yamamoto found no evidence was a strategic reassurance to Japan, but it was flawed.

Six months earlier, Australia had identified the need for a long-range bomber capacity. Three months earlier, Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) survey teams were conducting feasibility studies into building such a capability in the Kimberleys. Drysdale had neither appropriate terrain nor geography to expand, but neighbouring Anjo Peninsula did. It was physically closest to Java, Japan’s central administrative hub for the Dutch East Indies, and had the expanse necessary for a purpose-built base. Designed to accommodate and support heavy bombers and their requisite ground staff, by mid-1944 Anjo Airfield would begin to prove its worth. Within months the staging platform increasingly helped route, destroy, and disrupt Japanese forces out of the region.

Although it is easy to dismiss Yamamoto’s mission as a Japanese intelligence failure, it was a successful test case for Japanese reconnoitre capabilities. He had proven that a small boat could reach Australia undetected, small crews could land unnoticed, activities could be conducted uninterrupted, and then safely depart again. It was the type of small-scale landing that could have been used for diversionary operations. For example, Java-based small fishing boat flotillas could sail across the Timor Sea, severing vital subsurface telegraph cables along the way, not only disrupting vital lines of communication isolating Australia from Allied support, but also disabling the future use of northernmost Australia in future anti-Japanese counteroffensive operations. A subsurface warfare prospect not that dissimilar to contemporary potential South China Sea actions disrupting the global internet.

As one of the few confirmed, successful wartime Japanese special operations missions into Australia, there can be little doubt that northern Western Australia’s tyranny of distance, was paradoxically also one of the country’s main defences. Either way, Yamamoto’s Matsu Kikan special operations intelligence mission had done its job.

Select Bibliography

CinCPac-CinCPOA Bullettin 142-45, Japanese Naval Shipbuilding “Know Your Enemy!, 4 June 1945, University Reprints 2013 (January 1, 2013).

Dunlop, E.E. The War Diaries of Weary Dunlop Java and the Burma-Thailand Railway 1942-1945 (Castle Hill: Thomas Nelson Australia, 1986).

Felton, Mark. Japan’s Gestapo: Murder, Mayhem and Torture in Wartime Asia (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military, 2012).

Felton, Mark. The Fujita Plan (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2006).

Fujiwara, Iwaichi Lt General. F. Kikan: Japanese Army Intelligence Operations in Southeast Asia During World War II. Trans: Akashi Yoji (Hong Kong: Heinemann, 1983).

JACAR C13072095600, Lt (Res.) TAZAKI, Sueo (Kaigun Jireo Koho [Navy List] 1944(1) – Part 19), jacar.archives.jp.go. Trans. K. Reid-Smith 11 August 2021.

Keegan, John. Intelligence in War (New York: Vintage Books, 2002).

Llewelyn, James. The Imperial Japanese Army’s Tokumu Kikan – Special Service Organisations: connections between wartime and peacetime intelligence activities. Journal of Intelligence History, https://doi.org/10.1080/16161262.2021.1889277, published online 11 February, 2021 (accessed 15 August 2021).

Lockwood, Douglas. Australia’s Pearl Harbour Darwin 1942 (Sydney: Rigby Limited, 1977).

McArthur, Ian. The soldier who invaded Australia, in Australasian Post, March, 14, 1985.

Mellon, Gus. Email to Kate Reid-Smith. 4 August 2021.

NAA: A3269, O8/A The Official History of the Operations and Administration of Special Operations Australia (SOA), also known as the InterAllied Services Department (ISD) and Services Reconnaissance Department (SRD) Volume 2 – Operations {606 pages].

NAA: A5954, 249/22 RAAF Landing ground at Anjo Peninsula, North-Western Australia. War Cabinet Agendum No. 26/1944.

NAA: A9716, 1374 RAAF Directorate of Works and Buildings – Engineer Intelligence Section at Truscott (Anjo Peninsular) WA.

NAA: A12259, 1/19/AIR PART 1 Anjo Peninsula – Report on Beach Landings and Preliminary Work.

Nish, Ian. The Japanese in War and Peace, 1942-1948: Selected Documents from a Translator’s Intray (Folkestone, Kent: Global Oriental, 2011).

Nish, Ian and Mark Allen (eds). War, Conflict and Security in Japan and Asia-Pacific, 1941-52 The Writings of Louis Allen (Folkestone, Kent: Global Oriental, 2011).

Offenburg, Kurt. Japan at our Gates (Sydney: The Gale Publishing Company, 1942).

United States Strategic Bombing Survey (Pacific). Interrogations of Japanese Officials OPNAV-P-03-100. Interrogation Nav No 7 USSBS Nos 33, 45. Commander TH Moorer USN interrogation VADM Shiraichi Kzutaka IJN (Chief of Staff Second Fleet December 1941-March 1943) https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/AAF/USSBS/IJO/IJO-7.html (accessed 4 August 2021).