- Author

- Swinden, Greg

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2022 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Greg Swinden

If not for a newly released book and the recent death of a medal collector the name of Victoria Cross (VC) winner James Gorman would have remained consigned to the footnotes of Australian history. The book, A Wicked Noah’s Ark – The Nautical School Ships Vernon & Sobraon, by Sarah Luke was published in 2020, and the medal collector was Warwick George Cary who died in Sydney on 16 April 2020. Following Warwick Cary’s death his substantial medal collection was sold. James Gorman’s VC and his campaign medals were sold at auction in England in October 2020 for £297,600. The medals were purchased by a UK private buyer ‘with a strong interest in the Crimean War’. It is believed that this is Lord Ashcroft who has purchased over 180 Victoria Crosses, which are now on display at the Imperial War Museum in London1. A Wicked Noah’s Ark describes the trials and tribulations of the New South Wales nautical school ship scheme created in 1867 and in which James Gorman played a significant role, making the scheme a success before his death in 1882. So who was James Gorman?

James Gorman was born at Islington, London, on 21 August 1834, the son of Patrick Gorman, a nurseryman, and his wife Ann Gorman (née Furlong)2. James joined the Royal Navy, as a Boy 2nd Class on 2 March 1848, serving initially in the training ship HMS Victory (Admiral Nelson’s former flagship). In September 1848 he, together with several other boys, joined the 10-gun sloop HMS Rolla for a training cruise in the English Channel, prior to being allocated to other ships. Gorman impressed his instructors to such a degree that he was retained on-board Rolla to act as an assistant instructor for the next intake of boys.

He then served briefly in the frigate HMS Dragon before joining the 120-gun first rate ship HMS Howe and remaining on-board her until 12 July 1850. After a short stint in floating barracks (old ship hulks used for temporary accommodation) Gorman joined the 90-gun second rate ship HMS Albion as a Boy 1st Class on 13 July 1850. His service record described him as standing 5 feet 2 inches, with blue eyes, light brown hair and a ruddy complexion. Gorman was promoted Ordinary Seaman 2nd Class on 13 May 1852 and just two months later he was promoted Able Seaman and remained serving in Albion. In late 1853 fighting between Russian and Ottoman Turkish forces saw the commencement of what became more well known as the Crimean War. Britain and France offered support to the Turks and in mid-September 1854 British and French forces landed on the Crimean Peninsula, at Kalamita Bay, to the north of Sebastopol. Within days the Battle of Alma was fought (20 September 1854) with the Russians suffering heavy losses followed by fighting at Balaklava in October and the Allies laying siege to the port of Sebastopol. The Royal Navy played a major role in this war, not only escorting the transport and troop ships to the Black Sea and bombarding coastal ports but also by providing a substantial ‘Naval Brigade’ for service ashore.

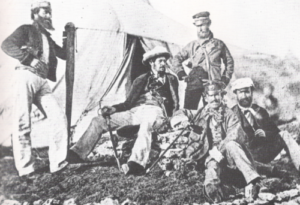

Two thousand sailors and two thousand Royal Marines were put ashore as naval infantry, manning 160 cannons of various calibre, taken from Royal Navy warships to become siege guns ashore. Several of Albion’s 8-inch guns were unloaded at Balaklava harbour, and amongst the 2,000 sailors landed was Able Seaman James Gorman. Under the command of Captain Stephen Lushington (Commanding Officer of Albion) the Naval Brigade was initially camped on Victoria Ridge about two miles to the south of Sebastopol harbour. Teams of ‘bluejackets’ manhandled the guns and ammunition from the harbour at Balaklava to the front line (about 7 miles away) where gun emplacements were constructed overlooking Sebastopol. Smaller guns such as 32‑pounder and 68-pounder weapons were also used. Each gun was supplied with 180 rounds of various ammunition plus gunpowder, all of which was taken ashore and moved to the frontline by sailors from the various ships.

The British siege positions before Sebastopol were divided into ‘Right Attack’ and ‘Left Attack’, on either side of the Victoria Ridge. The French siege positions lay between the coast near Sebastopol and met and secured the British left flank (Left Attack). Helping to reinforce the British right flank, the Naval Brigade manned 17 guns in Chapman’s Battery and 7 guns in Gordon’s Battery. Six of the new 68-pounder Lancaster guns (a rifled muzzle loading gun) were set up in two other batteries on Victoria Ridge and named Right and Left Lancaster Battery. The British right flank, however, was poorly-defined and vulnerable. This presented a weak point that the Russians chose to exploit. The morning of 5 November 1854 was misty with drizzling rain when the Russians, under the command of General Alexander Menshikov, launched a sudden and sustained attack on the British right flank and seized the heights of Inkerman. This action was later described as one of the of the bloodiest and most desperate battles in British military history. The Times war correspondent William Russell described the fighting as …a series of dreadful deeds of sanguinary hand-to-hand assaults – in glens and valleys, in brushwood glades and remote dells. In many cases the commanding officers of units could see little of the action and individual groups of soldiers were required to fight off the frenzied Russian attacks with little direction from their senior officers.

Able Seaman Gorman was located with the Right Lancaster Battery on Victoria Ridge. The Naval Brigade had already seen heavy fighting on 26 October when Russian forces had tried to seize the position. On 5 November the battery was attacked again and there was fierce hand to hand fighting as the Russians continued to surge forward time and time again in an attempt to overrun the British position. Gorman, and four other sailors from Albion (Thomas Geohegan, Thomas Reeves, Mark Scholefield and John Woods), mounted the gun battery parapet and kept up a rapid fire on the advancing Russians. Wounded British soldiers, lying in a trench below, greatly aided this defence by continuously reloading rifles and passing them up to the five sailors, thus allowing a continuous and unrelenting fusillade on the advancing enemy. Eventually reinforce-ments arrived and the Russians retreated but two of the sailors, Thomas Geohegan and John Woods, had been killed.

Gorman was later reported to have also saved the life of Captain Lushington when he was attacked by Russian soldiers and that Gorman was wounded in this exploit. In early December 1854 he was sent back to Albion to recover while Reeves and Scholefield continued to serve ashore until September 1855. In a report by Lushington to Queen Victoria dated 7 June 1856, Gorman, Reeves and Scholefield were each subsequently recommended for the award of a Victoria Cross for their bravery at the Battle of Inkerman.

This recommendation was accepted and the awards announced in the London Gazette (24 February 1857). The citation provided in Lushington’s letter stated: Thomas Reeves, Seaman, James Gorman, Seaman and Mark Scholefield, Seaman. At the Battle of Inkerman, 5 November 1854, when the Right Lancaster Battery was attacked, these three seamen mounted the Banquette, and under a heavy fire made use of the disabled soldiers’ muskets, which were loaded for them by others under the parapet. They are the survivors of five who performed the above action. Regrettably, at this time the Victoria Cross could not be awarded posthumously, thus Geohegan and Woods received no recognition despite displaying the same level of bravery and devotion to duty as the other three surviving seamen.3

By the time of the announcement of these awards Able Seaman Gorman was no longer serving in Albion. He had left the ship in January 1856 and served briefly in the 677-ton wooden vessel HMS Coquette, based at Woolwich, before being hospitalised at Haslar Royal Naval Hospital for rheumatism in March of that year. He rejoined Coquette in May 1856 but shortly after was discharged from the Royal Navy. Gorman re-enlisted in the Royal Navy as a Chatham Volunteer in mid-June 1856 and joined the 16-gun brig HMS Elk.

Elk was dispatched to the East Indies Station and in 1857-58 took part in the Second China War (1856-1860). The brig was present at the destruction of the Cantonese fleet at Fatshan Creek during 25 May – 1 June 1857, and later Gorman, now a leading seaman, served ashore in the Naval Brigade at the Battle of Canton (28 December 1857 – 5 January 1858). It was during his service in China that his Victoria Cross was presented to him on-board Elk but the exact date is not known.

Gorman was promoted to Petty Officer on 21 February 1858. In late 1858 Elk was attached to the Australia Station, arriving in Sydney on 31 December 1858. In early 1859 Elk, in company with HMVS Victoria, searched Bass Strait for the missing brig HMS Sappho which was believed to have sunk in the strait in late 1858, but no sign of the vessel was found. In March 1860 Elk left Sydney and returned to England.

After returning to England Gorman was discharged at Sheerness on 21 August 1860, thus ending his service in the Royal Navy4. He soon tired of life in England and in late 1862 embarked in the 755-ton trading vessel Fairlie at Plymouth and migrated to New South Wales, arriving in Sydney in mid-1863. Gorman took up residence in Kent Street, overlooking Darling Harbour, and worked as a sailmaker. He later moved to a dockside house in Sussex Street and on 10 November 1864 married Mary Ann Jackson with Anglican rites at St. Phillip’s Church, Sydney. A daughter Anne Elizabeth was born on 25 September 1865 but the marriage was short-lived as Mary Ann died of a fever in July 1866. She was only 23 and was buried in the Devonshire Street Cemetery.

On 17 April 1867, Gorman became the Drill Master and Gunnery Instructor on the Nautical School Ship Vernon. Theship was moored in Sydney Harbour (often near Cockatoo Island) and had been established as a means for educating under privileged boys, who would be schooled and also learn a trade. Many of the boys were orphans or had parents who were criminals and they were at risk of following a life of crime as well. In 1869 Gorman was appointed as the Master at Arms in charge of the lower deck, responsible for the discipline and welfare of the 135 boys on board Vernon. In 1872 he was advanced to Sail Maker and Officer-in-Charge of the lower deck, and in 1873 received a special mention in Superintendent James Seton Veitch Mein’s annual report, for the skilled nursing of the boys during a scarlet fever epidemic.

He left Vernon on 7 June 1878 with the rank of Second Mate and became Foreman of the Magazines on Spectacle Island (in the Parramatta River not far from Cockatoo Island). These gunpowder magazines were the first official naval stores buildings established in Australia with the powder magazine, built in 1865, still in use up until the 1980s. Gorman was initiated into the Masonic Leinster Marine Lodge of Australia in Sydney on 12 August 1878 and married Deborah King on 20 July 1881. He set up home with his daughter and new wife in a stone cottage on Spectacle Island.

On 15 October 1882, James Gorman suffered a severe stroke and died three days later. He was buried with military honours in the Church of England section of the Balmain Cemetery (now Pioneers Memorial Park, Leichhardt) on 20 October 1882. A large number of officers of the Masonic Grand Lodge of New South Wales also attended the funeral.

The Sydney Morning Herald dated 21 October 1882 wrote of Gorman’s exploits, stating: During the campaign he performed many deeds of bravery, foremost among which may be specially noted – saving the life of the late Admiral (then Captain) Lushington, R.N., when that officer was unhorsed and surrounded by the enemy; and the splendid deed of heroism for which Her Majesty decorated him with the Victoria Cross, protecting at the imminent risk of his life the wounded soldiers and sailors at the Lancaster Battery on the great day of Inkerman.

Three times were the English forced by overwhelming numbers to evacuate this work, and the dead and wounded lay in heaps; at length, notwithstanding the order to retire, Mr Gorman, with four other brave fellows, stood their ground until reinforcements arrived, and this important post was saved.’

James Gorman’s medals included the Victoria Cross with the reverse of the suspension bar inscribed ‘Seaman James Gorman’ and the reverse center of the cross dated ‘5 Nov. 1854’. His campaign medals consist of the Crimean War Medal 1854-56 with clasps Inkerman and Sebastopol, the Second China War Medal 1857-1860 with clasp Canton 1857 and the Turkish Crimean Medal 1854-56.

Notes:

After the Crimean War another sailor, James Devereaux of Southwark, London, claimed that he had joined the Royal Navy as James Gorman and had been awarded a Victoria Cross for his gallantry with the Naval Brigade in the Crimea. When he died in Southwark, London in 1889, his obituary appeared in the South London Press citing his Victoria Cross winning deeds. While never wearing or displaying his medals, Devereaux’s claim became accepted by successive historians and appeared in numerous reference works.

In 1947, when a British newspaper called for information on VC winners, a Mr. J. O. Devereaux, of Colchester, wrote to say that he was the son of James Devereaux, who had changed his name to Gorman, joined the Navy, and won the VC in the Crimean War. Mr Devereaux stated he had the VC and the other medals but there is no record of them ever being sighted.

The deception was finally uncovered in the 1980s by Mr Harry Willey (husband of James Gorman’s great-grand-daughter) along with Mr Anthony Staunton (co-editor of the second edition of They Dared Mightily, the Story of all the Australian VC Winners), Mr John Winton, author of the standard work on naval VCs and Mr Dennis Pillinger, curator of the Lummis VC and GC records of the Military Historical Society. The situation was put beyond doubt when the Australian descendants of James Gorman came forward with not only a portrait of him wearing his medals but also all his medals including the Victoria Cross. The Register of the Victoria Cross now contains the correct details and has removed any reference to James Devereaux.

VC winners were also granted an annual pension. British records show that Gorman’s VC winner pension was paid annually to him via the Military Commandant, Sydney, from at least 1871 until 1883, the year after his death, when …no payment was made. Another seaman named James Gorman, serving in the gunboat HMS Woodcock on the China Station in the late 1850s was also reported to have been wrongly paid the VC pension for at least two years. When this error was discovered this James Gorman was required to repay the money. He was then imprisoned in Hong Kong before being ‘discharged with disgrace’ from the Royal Navy.

There is also a possible third occasion when Gorman’s name was used. On 26 October 1916 James William Manning Begnell (born in late 1889 in Burwood, NSW) enlisted in the 3rd Battalion, 1st AIF, as Private (6997) James William Gorman. Perhaps a coincidence, but in 1905 Begnell was sent to the Nautical School Ship Sobraon, that had replaced Vernon in 1892, and served there until aged 18. By the time Begnell arrived onboard Sobraon James Gorman was long dead; but perhaps the story of the VC winner was told to the boys by older crewmen who had served in Vernon. Maybe Begnell deliberately chose Gorman’s surname to enlist under. No one will ever know as on 23 August 1918, near Chuignes during the Allied advance, Private James Gorman was cut down and killed by German machine gun fire. His body was never recovered and his name is now inscribed on the Villers Bretonneux Memorial in France.

Footnotes:

1 As James Gorman was a member of the Royal Navy his Victoria Cross was not deemed an ‘Australian VC’ even though he had resided in New South Wales for nearly 20 years. Therefore, it was not subject to the Australian Protection of Moveable Cultural Heritage Act 1986 preventing the overseas movement/sale of Victoria Crosses awarded to Australian personnel.

2 On his 1864 marriage certificate Gorman stated he was 29 years of age (instead of 30) and that his father’s Christian name was James.

3 The Victoria Crosses awarded to Reeves and Scholefield are both held in the Lord Ashcroft Collection at the Imperial War Museum in London. Thomas Reeves was born at Portsmouth in 1828 and he joined the Royal Navy in 1846. He was discharged medically unfit in 1860 and died on 4 August 1862 in Portsea, England. Mark Scholefield was born in London on 16 April 1828 but the date when he joined the Royal Navy is uncertain. He died at sea on 15 February 1858 while serving in the brig HMS Acorn (East Indies and China Station) and was buried at sea.

4 If James Gorman had continued to serve on the Australia Station it is possible he would have seen active service in the New Zealand War in mid-1860, when seamen from various Royal Navy ships were landed as part of a Naval Brigade to supplement British troops.