- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2020 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Nick Hordern

In 2020 we celebrate the 75th anniversary year of the opening of the Captain Cook Dock which joined Garden Island to the mainland and we gained a great strategic asset of a world class graving dock. The often overlooked social implications of this great engineering feat are discussed in this perceptive article.

By the 1970s, Kings Cross and its surrounds had become saturated with sleaze, epitomised by venues like the Venus Room, owned by vice czar Abe Saffron, and the Forbes Club, owned by gambling boss Perce Galea. Darlinghurst Road well deserved its nickname of ‘the dirty half-mile’.

But how did things come to this? The 19th century origins of the district encompassing Kings Cross, Potts Point and Elizabeth Bay were notably genteel, and as late as the 1940s it stood out as an island of respectability, prosperity and even glamour, surrounded by the impoverished morass of Woolloomooloo, Darlinghurst and Paddington. In Jon Cleary’s novel of wartime Sydney You Can’t See Round Corners, the gilded inhabitants of the Cross live ‘in perfectly sustained ignorance’ of the poverty across the valley in working class Paddington, home of the novel’s anti-hero, an Army deserter.

But during WWII the district took a distinct turn towards notoriety, partly as a result of the construction of the Captain Cook Graving Dock. At its peak in July 1943 this project employed over 4 100 men, and many of these were single or lived apart from their families in local accommodation. They did what well-paid men like to do – drink, gamble and have sex. The district around the Cross adapted itself to their needs and after the war the workforce dispersed, but the milieu remained.

In order to drink, gamble and have sex the graving dock workers had to break the law – and they weren’t the only ones doing so. Hundreds of thousands of Australian and Allied servicemen passed through wartime Sydney, and most of them wanted a drink. To do so, they usually had to get around the system of partial prohibition then current in NSW, known as ‘early closing’. Kings Cross floated on a sea of illicit alcohol – ‘sly grog’.

‘Early closing’ made it illegal to buy alcohol almost anywhere but hotels, wine bars and restaurants, and it could not be sold on Sundays or after 6.00 pm. This seemed clear enough – but then came a raft of confusing exceptions. Bona fide travellers were permitted to drink after 6.00 pm, as were diners if they had ordered their alcohol before that time. In at least some pubs, miners, dockyard workers coming off shift and, during the war, members of the armed forces were also permitted to drink outside regular hours. These loopholes meant that much of the time, in any room full of drinkers some were breaking the law and some weren’t: a recipe for corruption among the police charged with enforcing these unenforceable laws.

The Kings Cross district had a distinctly cosmopolitan edge, in part because the few European refugees fleeing Fascism who had made it to Sydney congregated there. The Claremont Café, at 99 Darlinghurst Road, was opened in 1939 by the German refugee Walter Magnus, and its patrons included actors Peter Finch and Chips Rafferty, artists Russell Drysdale, Donald Friend and William Dobell. Dame Mary Gilmore, the doyenne of Australian letters whose portrait appears on today’s $10 note, lived above the restaurant.

As an example of the anomalies of ‘early closing’, in 1941 Magnus was fined for selling a bottle of beer after 6 pm to a plainclothes policeman who had bought a meal. In his defence Magnus pointed out his regular customers included Sydney’s Great and Good, who consumed large quantities of liquor legally on a technicality, either because they pre-ordered their drinks or brought their own bottles. Media magnate Frank Packer had hosted a dinner at the Claremont for the US Consul General at which two dozen bottles of wine had been drunk. Examples like this fuelled the general feeling that early closing really meant one law for the rich and another for the poor.

Alcohol was the standout, but gambling (other than at racecourses) and prostitution were also prohibited. And as the war progressed alcohol, along with a whole range of goods – petrol, tyres, cigarettes and clothes – were rationed, and could usually only be obtained illegally. The war brought full employment and higher wages; people had money in their pockets and the demand for these hard-to-get items fueled a flourishing black market. And while many of the suppliers were criminals – Abe Saffron got his start in the wartime liquor trade, Perce Galea his in a wartime gambling club – the bulk of their customers, including servicemen, who were drinking or gambling illegally or trading on the black market were otherwise law-abiding.

The black market wasn’t the only contributor to wartime crime. There was the ‘brownout’ – regulations introduced after the outbreak of the Pacific War required households and businesses to shield their lights, in order to prevent enemy aircraft identifying targets. It didn’t work very well: when the Japanese conducted their first reconnaissance flight over Sydney in the small hours of 17 February 1942, carried out by a floatplane launched from a surfaced submarine, the pilot had no difficulty navigating. He used two sources of light which were exempt from the brownout regulations: Macquarie Lighthouse at South Head and the blaze of arc lights illuminating the round-the-clock construction work on the Captain Cook Graving Dock. But the brownout did provide cover for muggings, assaults and other forms of anti-social behavior, such as people simply hurling garbage out of apartment windows under cover of dark, rather than walking downstairs and putting it in a bin. It also threw a cloak over prostitutes who worked in public places, like the convenient spaces between the buttress roots of the fig trees in Rushcutters Bay Park.

Kings Cross and the district around it really came into its own by catering for war aphrodisia – the universal phenomenon that wartime sees a sharp rise in sexual activity outside of peacetime norms. This was a marked feature of life in many cities in WWII, and Sydney was no exception. The phenomenon was boosted after the outbreak of the Pacific War brought a flood of American personnel to Sydney.

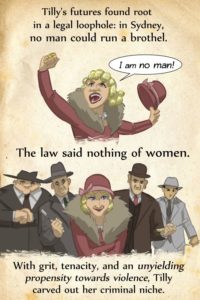

The main red light district was in Darlinghurst, to the south west of Kings Cross proper. Darlinghurst was the domain of vice queens like Tilly Devine and Nellie Cameron. Devine’s brothel at 191 Palmer Street became notorious for ‘gingering’; robbing customers while their attention was elsewhere. Because they tended to carry large amounts of cash, American servicemen were particular targets of gingering and in 1943 New South Wales introduced the Disorderly Houses Act specifically to deal with this issue. This made it an offence simply to be on specified premises; Devine’s house was the first to be ‘declared’.

In his other novel of wartime Sydney, Climate of Courage, Jon Cleary described war aphrodisia as ‘an air of electric nervousness’ that set in at dusk; restraint became ‘a wartime casualty…replaced by the roving eye and the calculating mind’. And it wasn’t just professional sex workers who seized on the opportunities offered by the war. Other women, known as ‘good time girls’, turned to amateur prostitution, seeking out clients in cafés and at private parties.

But the impact of war aphrodisia wasn’t restricted to prostitution, professional or amateur: it was contagious. The side effects of the war – lengthy separations, tedious wartime jobs, a thriving black market, a dearth of familiar partners accompanied by an influx of exotic strangers – all conspired to undermine peacetime taboos. Just as many ordinarily law-abiding people traded on the black market, lots of people had affairs they probably would not have embarked on in peacetime.

In April 1943, a Justice Edwards in the Divorce Court heard an application from 23 year old Private Victor Morris, who had just returned from an eighteen months deployment in the Middle East with the AIF’s 9th Division. Prior to the reforms of the 1970s, the grounds for divorce were restricted to adultery, cruelty and desertion, and Morris accused his wife Marion of adultery. She denied it, but her landlady at 34 Kings Cross Road testified that she had seen a string of men going in and out of the Morris flat. Granting the divorce, Justice Edwards intoned that ‘it is deplorable that young husbands cannot go to war and leaves their wives behind in safety’. There was no suggestion that Marion was engaged in outright prostitution, but Edwards took a particular swipe at her, saying that her behavior had been ‘all the more reprehensible’ because she had been receiving money from her husband as well as an allowance from the government.

The judge spoke for those moralists who were outraged by war aphrodisia. Prominent among these was the Reverend C.H. Tomlinson, President of the NSW Temperance Alliance, who thundered that ‘wives who are faithless to their husbands are moral lepers, and are more debased than if they gave themselves to the Japanese barbarians their husbands are fighting’.

Nevertheless, the women of Sydney found a voice in the novel Come in Spinner by Dymphna Cusack and Florence James, the most comprehensive single picture we have of the city during WWII. On its large canvas are depicted a whole range of discreditable and unpatriotic behaviours: adultery, prostitution, drink-spiking, rape, illicit gambling, consuming illicit alcohol, abortion, infidelity, profiteering, snobbery – a vanity fair in wartime Sydney. And much of the novel’s action takes place in and around Kings Cross.

During the war Cusack worked as the caretaker of a block of flats in Orwell Street Kings Cross and James as a welfare officer for a hospital, so both came across plenty of examples of the desperate situations women were plunged into at the time. Like unplanned pregnancy, at a time when the prohibitions on abortion were far more draconian than they became after the partial decriminalization of the 1970s. As a result abortion in the 1940s was a lethal racket, something Cusack and James were keen to expose.

One of their characters is a young woman, a member of the Australian Women’s Army Service, who falls pregnant to a fellow serviceman who tells her he will divorce his wife to marry her. When she finds out she has been lied to, she is chivvied into having an abortion by her sister, who is worried about the effect an illegitimate child will have on the family’s reputation. She has an abortion, carried out by a doctor, not in a clinic but in an ordinary Elizabeth Bay flat used for the purpose. She dies as a result of the procedure.

Another is a 16 year old girl from the suburbs. Stuck in a boring factory job in a textile mill, she comes into the city for a night out; falls in with a bunch of ‘good time girls’, is drugged by an American, raped and forced into prostitution.

Another is locked in a relationship with a man who is a loser on two counts; he lacks the willpower to leave his wife in order to marry her, and he keeps on losing money at the baccarat table. He regularly attends a baccarat game which moves from private flat to private flat in the Kings Cross area.

Written in 1945-1946, Come in Spinner was remarkable for its time, and remains so, because it upends the conventional depiction of war as a saga of male heroism and endeavor. Cusack and James argued that with the exception of men actually on the front line – only a small proportion of those in uniform – it was Sydney’s women and children who bore the brunt of the war.

No sketch of wartime Kings Cross would be complete without a reference to the Great Rat Plague. This began in the wake of the introduction of meat rationing in January 1944. Unable to feed them, people got rid of their cats and dogs, the rat population exploded, and soon the newspapers were running stories of people being bitten in their sleep and women being attacked in their kitchens by rats as big as cats.

Although ‘the dirty half-mile’ was two decades in the future, the rats were a portent of things to come.

Nick Hordern is the co-author, with Michael Duffy, of two histories of the Sydney underworld: Sydney Noir, which covers the period 1966-1972; and World War Noir, which covers 1939-1945. Both are published by NewSouth Publishing.