- Author

- Gould, R.T., Lieutenant Cdr , RN

- Subjects

- History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 1995 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

As evidence of his abilities, Harrison brought with him specimens of two original inventions which he had successfully applied to his clocks – a form of pendulum (known, from its appearance, as the “gridiron”) composed of brass and steel rods so arranged that its period of vibration was virtually unaffected by changes of temperature; and a complicated but highly efficient escapement (known as the “grasshopper”) which never needed oiling and gave an almost continuous impulse with a minimum of friction. He had already built two clocks embodying these inventions, and they had proved themselves capable of going with unprecedented accuracy, their errors never amounting over long periods to as much as one second a month.

Before calling on the Board, Harrison visited Halley, then Astronomer Royal, and George Graham (another north-country man), the leading London clockmaker. They warned Harrison that there was no hope of the Board advancing a penny on the strength of his drawings alone – but Graham solved the problem of funds by advancing him, then and there, £200 out of his own pocket without asking either interest or security. Harrison returned to Barrow and spent the next six years in building his No. 1 marine timekeeper.

The modern chronometer is really a large and perfect watch, but in designing No. 1, the first accurate marine timekeeper ever made, Harrison did not attempt to conform with the pocket watches of his day. He was perfectly capable of making them and, as after events showed, of improving them; but he knew that the best of them could not be trusted even to within five minutes a day. To win the £20,000 reward the extreme permissible error was three seconds a day – a degree of accuracy which had scarcely been reached, except for Harrison’s pair, by any clock designed for use on shore, with all the extra advantages conferred by a fixed, motionless support and by the use of a pendulum.

Harrison redesigned his improved grandfather clocks for use at sea. In doing so he grappled with and overcame difficulties which had baffled all his predecessors.

The main mechanical difficulty was twofold. A pendulum cannot be used advantageously at sea, so a marine timekeeper must be governed by a vibrating “balance,” controlled by a spring. For accurate timekeeping that balance must have a perfectly constant period of vibration. In anything but the calmest weather the incessant varying motion of the ship would tend to alter the extent and the period of every vibration. Again, the slightest alterations of temperature would have a most marked effect upon the controlling spring – relaxing it in heat, stiffening it in cold, and causing the timekeeper to go either slow or fast. The error induced was approximately one minute a day for an alteration in temperature of only 10°.

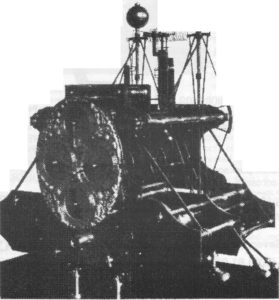

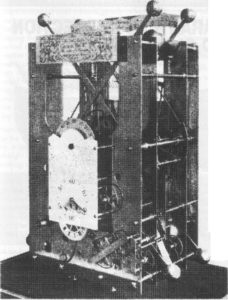

Harrison most ingeniously eliminated the errors caused by the ships’ motion. He replaced his pendulum, not by a single balance, but by two – a pair of huge straight-bar balances weighing 6½ lb each and vibrating seconds. They were arranged side by side and connected by fine cross-wires so that their motions were always exactly opposed – as if they were geared together, but with far less friction than gearing would entail. Any motion of the ship thus tended to accelerate the period of one balance exactly as much as it retarded the other – and the total effect upon the coupled motion of the pair was nil. The balances were controlled by four helical springs in tension, and Harrison applied to these a reversed form of his brass-and-steel “gridiron,” so arranged that it automatically altered the tension of the springs exactly enough to counterbalance their own weakening in heat or strengthening in cold.

The balances, and most of the wheels, are mounted on anti-friction wheels, and move with remarkable freedom. There are two escapements, of Harrison’s ‘grasshopper’ pattern, having lignum vitae pallets controlled by small springs. The escape wheel is of hard brass, but all the remainder (ranging up to some 14 in. in diameter) are of oak, with mortised oak teeth. The machine is driven by two mainsprings, driving a single central fusee, and is provided with an auxiliary spring to keep it going while the mainsprings are rewound (every twenty-four hours). An attractive feature is the decorated oval dial-plate, carrying four small dials indicating seconds, minutes, hours and days.