- Author

- Gould, R.T., Lieutenant Cdr , RN

- Subjects

- History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 1995 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Having tested No. l successfully on board a barge in the River Humber, Harrison brought it to London in the spring of 1736. Graham, Halley and others of the Royal Society saw and praised it, and on their recommendations the Admiralty allowed it to be embarked, with its maker, on board H.M.S. Centurion (afterwards Anson’s famous ship) for a voyage to Lisbon. The chronometer was transferred to H.M.S. Oxford for the return voyage, and her log (May 30, 1736) contains the first reference to Harrison in any Admiralty document.

An official certificate of No. 1’s trustworthiness was given to Harrison by the Master of the Oxford.

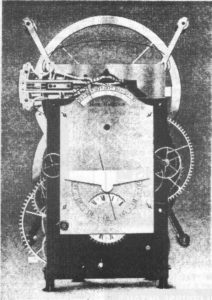

This certificate shows clearly that No. 1’s accidental errors of timekeeping – after having allowed, as is done with all chronometers, for its ascertained rate of going – must have been trifling – a few seconds at most. Its performance was an eye-opener to all who had the slightest inkling of the difficulties which Harrison had faced and conquered. No. 1 chronometer, however, was far from perfect. In 1737-39 Harrison built a second machine embodying the lessons taught by No. 1’s voyage. No. 2 is much more strongly built, its mechanism being almost completely housed between stiff plates of brass. The wheels are now entirely of brass (although their pinions still have wooden rollers), and the mainsprings are no longer used to drive the balances direct, but only to wind up, sixteen times an hour, two small springs which impel the balances with almost constant force. To this plan, which is known as a “remontoire,” Harrison adhered, with variations, in all his later timekeepers.

753 Separate Parts

No. 2 was never tried at sea. Soon after having completed it, Harrison set to work on a third timekeeper of different design, which he expected to be his masterpiece, and on which he spent no fewer than seventeen years (1740-57). No. 3 chronometer is smaller than either No. 1 (70 lb) or No. 2 (103 lb), as it weighs only 66 lb. It is also much more complicated than either, containing 753 separate parts. The same system of twin coupled balances is retained, but now the balances are of circular form, not straight, weighted bars. There is a single spiral balance-spring to control both of them, and this is compensated for temperature by a compound strip of brass and steel riveted together. Brass expanding and contracting more than steel, this strip bends one way in heat and the other way in cold. By so doing it alters the effective length of the balance spring. This plan is the forerunner of all the bimetallic “compensations” used today in chronometers and high-class watches.

No. 3 has a half-minute remontoire. It is really composed of two clocks – a small clock which does the timekeeping and one which will go only for about forty seconds, and another clock whose sole function is to rewind the little clock every half minute. Its mechanism exhibits enormous elaboration in detail.

In 1757-59 Harrison and his son William made a fourth and much smaller timekeeper, which was originally intended to be used as auxiliary to No. 3 – to carry the time from the big machine to an observatory, or vice-versa. But when No. 4 was finished its maker found that it was quite as good a timekeeper as No. 3, while much more portable and less liable to accidental damage.

No. 4 chronometer

No. 4 is simply a large watch in a silver case some 5 in. across. It embodies, in much reduced form, most of the principal improvements fitted in No. 3, but the anti-friction wheels are replaced by jewelled bearings and the bulky “grasshopper” escapement by an improved form of the ordinary “verge” watch escapement, with diamond pallets. The driving spring is rewound by the mainspring every 7½ seconds. The brass plates housing the mechanism are most elaborately decorated, as is also the enamel dial.

In March 1761 Harrison applied to the Board of Longitude for a trial of No. 4 in competition for the £20,000 reward. In November of that year H.M.S. Deptford, with William Harrison and No. 4 chronometer on board, sailed for Jamaica. Captain Digges of the Deptford shaped course to touch at Madeira, and after nine days at sea the ship’s longitude, by dead reckoning, was 13° 50′ W. (from Greenwich), while by No. 4 it was 15° 19′ W. William Harrison, justifiably confident of No. 4’s powers, maintained forcibly that the timekeeper was correct, and that if Madeira were correctly shown on the charts they ought to sight it the following morning.