- Author

- Gould, R.T., Lieutenant Cdr , RN

- Subjects

- History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 1995 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Accordingly, although Digges offered to lay five to one that No. 4 was wrong, he held on his course – and sighted Madeira next morning (December 9).

When the Deptford reached Jamaica on January 21, 1762, No. 4’s error, after allowance had been made for its declared rate, was found by observations to be five seconds, corresponding to 1¼ minutes of longitude – in the latitude of Jamaica, rather less than one geographical mile, as against the thirty allowed by the Act of Queen Anne. Accordingly, under this act Harrison, became entitled, provided that he could show his wonderful timekeeper to be a “generally practicable and useful” means of finding longitude, to the reward of £20,000. This he most thoroughly deserved, for the great and famous “problem of the longitude” which had baffled Newton, Leibniz, Halley and a hundred others, was definitely solved at last.

The Board of Longitude, however, thought otherwise. Although they had advanced Harrison £2,500 on account of the full reward, they insisted on a second official trial. This, after a good deal of wrangling, took place in 1764.

William Harrison and No. 4 chronometer were sent in H.M.S. Tartar to Barbados. Its error at Barbados was found to be 38.4 seconds in seven weeks, corresponding to 9.6 geographical miles. In the round voyage its total error, allowing for changes of rate at different temperatures, was a loss of fifteen seconds in five months, or an error of less than one-tenth of a second a day.

Still the Board’s doubts were not fully removed and much paper warfare ensued. Ultimately, on October 28, 1765, they paid Harrison another £7,500 – making £10,000 in all – on condition that he delivered to them, in trust for the public, all four of his timekeepers with a full description, in writing, of No. 4. They flatly refused to pay the other half of the Parliamentary reward unless and until Harrison made two more timekeepers and submitted them to such tests and official trials as they might see fit to impose.

Harrison was then over seventy, and his sight was failing. As he himself said, he regarded the second half of the reward as lost to him forever. He made no attempt to comply with the Board’s requirements – but in 1770 he and his son managed to complete his last timekeeper, No. 5.

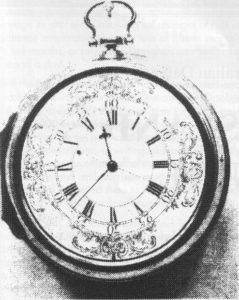

It was almost a duplicate of No. 4, but less ornamental, and with one or two slight mechanical improvements. In the same year Larcum Kendall, a London watchmaker, also completed a duplicate No. 4 commissioned by the Board of Longitude. Although virtually an exact facsimile down to the smallest screw, it was even better finished. Having been sent to sea with Captain Cook in his second (Antarctic) voyage of 1772-75, it performed magnificently. During three years of strenuous service, in which extreme cold alternated with tropical heat, an flat calm with furious gales, Cook – at first rather skeptical – wrote of it as “our trusty friend, the Watch,” and “our never-failing guide.” He made a special point of requesting its issue to him for his third voyage.

Meanwhile Harrison had won his fight with the Board of Longitude. The published accounts of No. 4’s trials had reached King George III’s ears, and in due course the two Harrisons were summoned to Windsor. The old inventor told the story of his long struggle, first with the mechanical difficulties and then with the Board, to a sympathetic listener – for King George always had a warm corner in his heart for science and invention of all kinds: He was heard to remark, “These people have been cruelly wronged” -and then, explosively, “By God, Harrison, I’ll see you righted!”

And thereafter he did his best to deal faithfully with the Board.

As a preliminary, No.5 was tested at the King’s own observatory at Kew, and went for ten weeks with a total error of only 4½ seconds. This being an unofficial test, the Board declined to take it into account – whereupon Harrison, backed by the King’s Parliamentary influence, presented a petition to the House of Commons (April 1772) setting out his claim to the second half of the £20,000 reward. The Board not expecting to find themselves on the defensive and discovering that the sense of the House was strongly against them, bowed to the storm.