- Author

- Turner, Mike

- Subjects

- History - general, Biographies and personal histories, Ship design and development, Naval technology

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2014 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

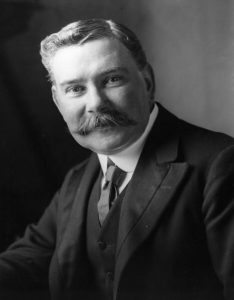

By Mike Turner

Louis Brennan was a brilliant and prolific inventor. Two of his best known inventions were a gyro-stabilised train for a monorail and a type of helicopter, but by far his most important invention was a torpedo that was the world’s first practical guided missile. Although Brennan spent most of his life in England he was educated in Melbourne where he commenced the development of his torpedo with technical assistance from the University of Melbourne as well as financial backing by Melbourne businessmen and the Victorian Government.

Louis Philip Brennan was born on 28 January 1852 at Castlebar, County Mayo, Ireland. He was the tenth child of Thomas Brennan, a hardware merchant, and his wife Honor (nee McDonnell). His elder brother Patrick John went to Australia in 1856 and became a teacher in Melbourne. In 1861 Louis, then aged 9, emigrated from Ireland with his parents to the gold rush boomtown of Melbourne. Louis had a keen interest in how all his mechanical toys worked, and experimented on extending their use and efficiency. He became an excellent student at evening classes at the Collingwood School for Design, founded by a prominent public figure Joel Eade in 1871 for ‘rising operatives’.1 In 1873 at Melbourne’s Juvenile Industries Exhibition Brennan showed some of his work, such as a window safety latch, a mincing machine and a billiard marker adopted by manufacturers Alcock & Company.

Louis was apprenticed to Alexander Kennedy Smith, a wealthy Scotsman who ran the biggest foundry in Melbourne. Smith was a renowned civil and mechanical engineer and encouraged Brennan. Smith was also a Major in the Victoria Volunteer Artillery Regiment, a sister branch to the Victoria Torpedo Corps, and this was to prove invaluable for the inventor of a torpedo.2 Smith was Melbourne’s Lord Mayor in 1875-1876 and a member of the Victorian Legislative Assembly from1877 to1881.

Brennan was associated with printer William Calvert in designs for a number of inventive devices, including an incubator and a mini lift for stairs, and in 1872 jointly registered patents for an improved weighing machine.3 He held at least 38 patents in very diverse fields.

In 1874, with advice and encouragement from William Charles Kernot, lecturer (and later Professor of Engineering) at the University of Melbourne, at age 22 Brennan commenced the development of a wire guided torpedo. Kernot performed numerous calculations, and was later paid £500 by Brennan in recognition of past assistance. Brennan and Calvert registered patents for the torpedo, and British Patent No. 3359 was granted on 4 September 1877. In the state’s legislature on 2 October 1877 A.K. Smith raised the matter of a grant to the company and £700 was received from the Victorian Government.4 Shortly afterwards the Brennan Torpedo Company was formed with Melbourne businessmen John Temperley and Charles and Edwin Millar to promote the torpedo commercially.

A public demonstration was conducted in Hobsons Bay, Melbourne in 1879, witnessed by various senior Navy and Army officers. A small target boat was hit at a range of 370 meters and the observers were impressed. A favourable report was sent to the Admiralty in 1879 by Rear Admiral J. Wilson RN, Commodore Royal Navy Australian Squadron.5 In 1881, on the invitation of the Admiralty, Brennan and Temperley went to England with the torpedo and it was examined at HMS Vernon. The Admiralty refused to bear the cost of future trials since they felt that the torpedo was unsuitable for use from ships. So Brennan and Temperley approached the War Department. The War Department showed interest and the Admiralty arranged an inspection on 23 June 1881 by Lieutenant Colonel Lyon, Royal Artillery and RN officers. Although the Admiralty was not directly interested in the torpedo it agreed to assist in trials by the Royal Engineers with a view to coastal defence. A favourable trials report prepared by a Royal Engineers committee in May 1882 recommended that further trials be conducted at the expense of the British Government.

Brennan and Temperley continued the development of the torpedo. They were assisted by the Royal Engineers and used workshops at Brompton Barracks, Chatham. In 1893 Brennan proclaimed that the torpedo was ready for testing, and Garrison Point Fort, Sheerness was selected as the trials site. On 13 March 1893 Brennan was given £3,000 to cover his expenses to date and put on an annual salary of £1,000 for three years or until two months after notification of the fitness for trial of the torpedo. Following a trial on 26 October 1886 the Admiralty declared that the torpedo was unsuitable for the Royal Navy but was very desirable for coastal defence using shore launching. The War Office recognised the value of the torpedo for coastal defence and negotiated an agreement agreed by Parliament on 10 March 1887. The payment of £110,000 was a vast sum (about 20 million in current Australian dollars), but it provided the War Office with exclusive use of the torpedo. A factory for torpedoes and associated equipment, the Government Torpedo Manufacturing Plant, was set up at Gillingham with Brennan as Superintendent and Temperley as his assistant. Brennan was to receive £1,500 per annum and Temperley £1,200 per annum. Further development of the torpedo was undertaken whilst shore stations for coastal defence were being installed, the last shore station being completed in November 1894.

In May 1892 Brennan was awarded a Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB) for his work on the torpedo. Louis married Anna Mary Quinn, also a native of Castlebar, in Dublin on 10 September 1892. They lived in Gillingham overlooking the River Medway. He had an incredibly fertile brain and frequently had ideas during the night. He avoided disturbing his wife by inventing the ‘Brennanograph’, a silent five-key typewriter similar to those used by stenographers in law courts. He was replaced by a Royal Engineer Officer as Superintendent in 1895, but was retained as a consultant until 1907.

Able to turn his mind to other matters and using money he had acquired from his torpedo, he invented a monorail train stabilised by a gyroscope and devoted twelve years to its development. He persuaded the War Department to let him use the vacant torpedo factory for development. The 20 tonne prototype carriage was propelled by a 60 kW petrol engine, and a 15 kW petrol engine drove two electric motors for two gyroscopes.6 Brennan envisaged a train of six carriages travelling at 330 kph, each carriage with its own gyro stabilisers which, inter alia, enabled a carriage to lean into a bend in the monorail. Sir Winston Churchill actively supported it and saw it as an invention which promised to revolutionise the railway systems of the world. Churchill bullied the India Office into giving Brennan a secret grant of £5,000. Using gyro stabilisation the monorail could traverse a chasm on a single steel cable, and the press dubbed the monorail the ‘Blondin railway’ after the famous tightrope walker. The Maharajah of Kashmir was convinced that the monorail would be the ideal way to traverse Himalayan foothills and he also gave Brennan a grant of £5,000. It won the highest award at the Japan-British Exhibition in 1910. But there was to be no more development after the prototype stage, apparently due to concern that the gyros might fail. Brennan had spent so much money on the monorail that he was forced to sell his home and return to work.

After being employed with the Ministry of Munitions from 1910 to 1918 he moved to the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough where he worked from 1919 to 1926 on a type of helicopter. It had an empty weight of 1,360 kg and had a single 18 m rotor.7 Propellers at the rotor tips produced torqueless rotation and a tail rotor was not required. Power was by a Bentley BR-2 170 kW rotary driving transmission shafts that ran down the length of the blades. It could hover successfully but proved difficult to handle in forward flight. The helicopter project was cancelled in February 1926 after the helicopter crashed, and official interest turned to the Clierva type autogyro. Brennan was devastated but continued with development as a private venture and it eventually drained his finances.

Brennan’s private life was in stark contrast to his brilliant career. At least five of his ten siblings died as small children in the 1840s during the Irish Famine. One of his two daughters died in the flu epidemic that followed the First World War.8 His wife died in 1931, and Brennan was knocked down by a motorcar on 26 December 1931 whist holidaying in Montreux, Switzerland. He died there from his injuries on 17 January 1932, and was survived by an only son and a daughter. His son, Captain Michael Brennan, RE, had a distinguished war record during World War I and died on 21 November 1933, less than two years after his father.

The Brennan Torpedo

Germany is generally credited with the first practicable guided weapon, the aircraft radio controlled Ruhrstahl SD 1400 (‘Fritz X’) guide bomb which entered service in 1943.9 It is not generally known that the first practical guided weapon was a wire guided torpedo designed in Australia by Brennan and patented in 1877.

The Brennan torpedo was similar in size to current submarine launched torpedoes such as the American Mark 48 in RAN submarines. It was much larger that the contemporary Mark 3 Whitehead torpedo which had a weight of 384 kg and a length of 3.6 m.10 Data on speed and range is conflicting. The maximum range is generally reported as 1,800 m, but appears to refer to the length of wire. Analysis of torpedo motion shows the range to be the length of wire reduced by two significant factors, one the propeller efficiency and the other depending on torpedo hydrodynamic drag and wire tension. The following speed and ranges are best estimates.

Weight: 1 tonne (approx.)

Length: 6.4 m

Cross section: Oval, 68 x 53 cm

Warhead: 100 kg guncotton

Maximum speed: 27 knots for 900 m

Maximum range: At least 1100 m

The main charge was 100 kg of wet guncotton initiated by a dry guncotton primer and a 77 grain Mark III torpedo detonator fired by an inertia pistol. The main charge had to be kept wet to prevent spontaneous detonation. The main charge chamber was regularly weighed to ensure that the guncotton had not dried out. Carbolic solution was added to restore the weight to the required value if the weight of the chamber decreased by more than two percent below the required value.

In contact with a hull the main charge was large enough to sink even the largest warships in service circa 1900. During the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-1905 the Russians laid their Model 1898 moored contact mine which had a main charge of only 56 kg of guncotton.11 Despite the small main charge the Japanese lost two battleships.12

Torpedo propulsion and guidance by two wires

The Brennan torpedo had two contra-rotating propellers powered by two shafts, one shaft surrounding the other. The forward propeller was powered by the outer shaft, and the aft propeller by the inner shaft. Each shaft was independently powered by its own wire drum containing 1,800 m of 1.8 mm diameter wire. Both wires were unwound by a shore station winch, and wire tension provided propeller shaft torque. The propellers acted like tug propellers and the total propeller thrust exceeded torpedo hydrodynamic drag by a ‘tow load’ equal to the total wire tension, generally 4 kN (400 kg). Depth was controlled by the forward planes driven by a servo mechanism in the ‘depth mechanism’. Depth input for the servo mechanism was measured by a hydrostatic valve in the nose.

The wire guidance used by Brennan is not to be confused with the wire guidance used by modern submarine torpedoes. Currently ‘wire’ refers to a thin electric cable trailed by the torpedo to the launching submarine.

As shown in Figure 1, each wire is unwound from its drum and passes around a reciprocating pulley travelling fore and aft in synchronisation with drum rotation. The two wires run around two pulleys known as ‘steering drive pulleys’, then inside the aft propeller shaft before leaving the torpedo. When a shore station made the wire speeds at the torpedo different the two steering drive pulleys rotated at different speeds. The difference in pulley speeds was the input to the steering mechanism which (by some unknown means) operated the four rudders, two at the bow and two at the stern.13 There was a 12 volt light at the top of a mast to assist the shore station steer the torpedo, and this light was only visible from astern.

Steering a torpedo

There were various versions of the ingenious system used in shore stations to guide the torpedo, and the data in this paper is for the final version. The shore station winch was driven by a steam engine of about 190 kW. The winch had a separating plate on its drum, and the two wires were wound onto their half of the drum at the same wire speed. Wire tension was automatically controlled by a hydraulic governor and recorded by a dynamometer. Torpedo speed and range could be varied by varying the wire tension.

Each wire passed around a steering pulley that could be moved along each side of a horizontal steering girder above the winch, and these two pulleys were initially side-by-side above the winch drum. Whilst the steering wheel was being turned the two steering pulleys moved at the same speed v in opposite directions along a horizontal beam, the steering pulley speed depending on the steering wheel speed of rotation. The difference in wire speeds was four times the steering pulley speed, Figure 2 refers. When the helmsman stopped turning the steering wheel the wire speeds at the torpedo reverted to the same speed and the torpedo rudders retained their angle when the steering pulleys stopped. Rudder angle returned to zero when the helmsman returned the two steering pulleys to their centralised side-by-side location.

This type of steering differs from conventional steering for a vessel where the rudder angle only depends on the steering wheel angle of rotation instead of the steering wheel speed of rotation.

Shore stations

The torpedo was accepted into service in 1887. Shore stations were installed at eight sites – River Thames (Cliffe Fort), Sheerness (Garrison Point Fort), Portsmouth (Cliff End, Isle of Wight), Plymouth (Pier Cellars), Cork Harbour (Fort Camden), Malta (Tigne and Ricasoli) and Hong Kong (Lye Mun). The Lye Mun station was for the Lei Yei Mun channel to Victoria Harbour. All sites had a Directing Station, Slipway, Wire Room, General Store, Boiler Room, Engine Room, Torpedo Room and Coal Store. Some sites had an Accumulator Room, Engine and Generator Room, and Workshop. The station was under the command of a Station Torpedo Officer responsible to the Local Officer Commanding Submarine Mining. The number of men at a station varied. At Cliffe Fort in 1904 the detachment was one Officer, one Mechanist, one Engine Driver, and seven other ranks, sometimes referred to as Brennists. There appear to have been twelve torpedoes at a home shore station and twenty four at shore stations abroad. When a torpedo was launched it ran down the slipway on a four-wheel trolley and the propellers were running before the torpedo entered the water. The torpedo was never fired in anger but there was an annual competition for the Brennan Torpedo Challenge Cup, shore stations firing twelve torpedos. Cliffe Fort won the 1906 competition and the results give an indication of the effectiveness of torpedo guidance. There were six hits and five misses by less than 30 m for twelve firings against targets at 28 to 31 knots and ranges of 450 to 1100 m.

Shore stations were operated in conjunction with minefields controlled by an electric cable from another shore station. Both types of station were manned by the Submarine Mining Branch of the Royal Engineers.14 Defence Electric Lights were used to define the areas of responsibility for controlled minefields and torpedoes.

Security was a prime concern and ‘All officers, non-commissioned officers and men employed in torpedo installations shall make and sign a declaration of secrecy, before the Commanding Royal Engineer.’15 Civilian workmen were restricted to their actual working area and also signed the form. To assist in torpedo security the depth and steering mechanisms were factory sealed, and the seals were regularly checked and recorded in a register by the Station Torpedo Officer. The Colony of Victoria provided financial assistance for the early development of the torpedo and requested the supply of torpedoes. This request was denied by The Secretary of State for War ‘until experience has shown what precautions may be necessary for the protection of the secret’.16

The Rifled Muzzle Loader Gun was replaced by the far more effective Breech Loader 9.2 inch gun. The latter was adopted for coastal defence (including Australia circa 1890) and Brennan stations were closed by 1911. The remains of some stations, such as Cliffe Fort, are still visible. Brennan torpedo No. 18 is on display at the Royal Engineers Museum, Gillingham, and a replica torpedo is on display at the Hong Kong Museum of Coastal Defence, Lye Mun.

Final Tribute to the Inventor Extraordinaire and Wizard of Oz

Louis Brennan was buried on 26 January 1932 in an unmarked grave in plot number 2454 at St Mary’s Cemetery, Kensal Green, London, an inconspicuous final resting place for such an internationally renowned and talented inventor. To redeem this situation, on 11 March 2014 Mr Enda Kenny, the Taoiseach (Irish Prime Minister), unveiled a new headstone and plaque at a Service of Thanksgiving and Remembrance dedicated to the man credited with inventing the steerable torpedo and monorail system. A wreath was laid by the Australian representative CMDR Dylan Findlater, RAN.

- Eade, Joel (1823-1911), Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 4, (MUP), 1972.

- Smith, Alexander Kennedy (1824 – 18881), Australian Dictionary of Biography,

adb.anu.edu.aui/biography/smith-alexander-kennedy-4597. (10 February 2014)

- Melbourne, The City Present & Past, Multimedia Content, Brennan Torpedo,

www.emelbourne.net.au/biogs/EM00231b.htm. (10 February 2014)

- Melbourne, The City Present & Past.

- Brennan Torpedo, en.wikipedia.org/wik/Brennan-torpedo (15 February 2014).

- Louis Brennan’s Heavyweight Balancing Act – The Gyro-Monorail, theoldmotor.com/ ?p=109924. (15 February 2014)

- Brennan helicopter –development history, photos, technical data

www.aviastar.org/helicopters_eng/brennan.php. (13 February 2014)

- The Brennan torpedo, Submerged, www.submerged.co.uk>Special Reports>Bombs And Bullets. (15 February)

- Glide bomb, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Glide_bomb. (22 January 2014)

- Whitehead Mark 3 Torpedo, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whitehead_Mark_3_torpedo. (22 January 2014)

- Russian/Soviet Mines, www.warships1.com/ WEapons?WAMRussian_Mines.htm. (18 February 2004).

- Cowie J.S., Mines, Minelayers and Minelaying, Oxford University Press, London, 1949, p35.

- Beanse reports that it has not been possible to examine the steering mechanism, and some components of the only extant torpedo are missing.

- Controlled mines were detonated when a target was seen to be in a suitable location. See Cowie, p24. All controlled minefields became an Admiralty responsibility in 1905.

- Memoranda for Station Torpedo Officer, Public Record Office (PRO) (UK) WO32/6065. (cited by Beanse).

- The Brennan Torpedo 1881-1887, PRO WO32/6065. (cited by Beanse).