- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, History - WW1, History - WW2, WWI operations

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Melville, HMAS Cerberus (Shore Establishment)

- Publication

- June 2014 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

These important memoirs provided by Robert Rayner are taken from his grandfather’s handwritten notes discovered in the family’s Sydney home in 2007.

Early Life in Prison!

I was born at Wandsworth Prison. Her Majesty’s Prison Wandsworth was built in the 1850s as a model establishment, becoming Britain’s largest prison now holding nearly 2,000 inmates. Here I entered the world on 15 October 1886 in the prison officer’s quarters. My father was Chief Medical Warder, later becoming Chief Warder. Our quarters were alongside the main gates, from the front we could see over the roadway to Wandsworth Common and the back overlooked the prison courtyard. In my schooldays, with my brother, we attended the Honeywell Road Public School, which was about one and a half miles from home and we went across the Common. In wet and foggy weather, my father used to come and meet us with overcoats and in winter carried a hurricane lamp, as there was no other lighting in those days. Father’s duties were from 6:00 am to 6:00 pm but he could get time off to meet us when the occasion arose.

My mother, Kate (nee Bradfield), died from cancer when I was five years old and father married again three years later. Stepmother, who was a wardress at the prison, was a very strict disciplinarian and we had to work hard in the home. Father, like most warders, had an allotment garden near the prison. He worked hard on the ground when he had time off and produced most of our vegetables and fruit such as raspberries, gooseberries, red and white currants. He made my brother and me a little truck which we used to collect manure from the streets for the garden; our reward was usually a half penny each, spent on aniseed balls, liquorice sticks or toffee.

I left school at 14, but previously on Saturday mornings helped the local baker deliver bread on his rounds with a hand cart and was usually rewarded with a bag of stale buns and rock cakes. Later I had a job at a chemist, cleaning the shop, making pills, delivering medicines and helping him poison unwanted cats and dogs. It was two miles from home and I went to work wet or fine. Later I landed a job at the Army and Navy Stores in Victoria Street in central London, at 4 shillings a week. This involved a long journey in a horse drawn tram. But later I found the quick cuts from home and spent my tram fares on a penny packet of five Wild Woodbine cigarettes. Later I was employed in the Optical Department selling field and opera glasses, barometers, spectacles and telescopes. My duties were to sweep and dust and wrap parcels for customers.

Joined the Royal Marines

Soon after I was 17, I could see no chance of being made an assistant at A & N Stores and had a feeling I would like to join the Army. One lunch time on 10 July 1903, I walked up to Trafalgar Square where a Recruiting Sergeant soon buttonholed me, told me of all the advantages of the Service. He was a big chap with a large nicely waxed moustache in a scarlet tunic, gold stripes and a red, white and blue emblem on his cap signifying ‘A Recruiter’. I told him I would see him the next day but said nothing at home. Next day I met him with other candidates and he took us to the Recruiting Office where we were duly measured, weighed and examined in reading, writing and arithmetic. Those of us that passed were duly sworn in and received the King’s shilling. I gave my notice at work and then returned to the Recruiting Office. The Colour Sergeant took us all to Lockhart’s opposite Trafalgar Square where we had a meal of ‘Baby’s Head’ (steak and kidney pudding), potato, mug of coffee and a slice of bread. He then took us all to Charing Cross Station, booked us in a compartment and we were off to the Deal Depot for training as a Royal Marine. We duly arrived and were met by a Sergeant and marched to the Barracks, put into the recruits Receiving Room, had a meal, found our beds and pillows, which were filled with straw. Next day we were taken to the barbers shop for a prison crop, then off to stores to be fitted with our uniform and duly vaccinated by the Medical Officer. On completion, we joined a squad of recruits and commenced nine months very, very hard and strenuous training. I am sure my parents were aware of my flight but I eventually wrote home. My father, who had served in the West Yorkshire Regiment for some years, wrote back saying ‘You have made your bed and must lie on it’.

Training commenced daily at 7:30 am and lasted until 4:00 pm. The Instructors were not bad but very strict. In education, we had to sit for 3rd, 2nd and 1st Class Certificates, and I managed these quite well. Footslogging on the parade ground was constant, had to learn all the movements as per the drill book of those days. Found the hob-nailed boots a bit heavy for a time but got used to them. Gymnastics and swimming were important subjects. Musketry and field training courses were severe and included long marches with full and heavy equipment. At the end of nine months training at Deal, I was transferred to Chatham Headquarters for more advanced courses in Musketry, Field Training and Parade Work and in addition a course in Naval Gunnery.

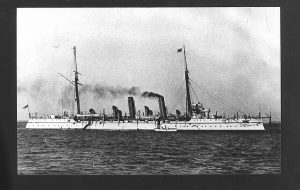

On completion of this training, I received my first draft chit to join HMS Pegasus at Sheerness. She was a third class cruiser of the Reserve Fleet, armed with 4.7 inch guns and 3 pounders plus 2 torpedo tubes. Our detachment of 21 Marines were employed painting ship, cleaning guns, cleaning mess decks and weekly Gunnery and Infantry Drill. Pay on embarkation increased from 8 to 10 pence a day. The ship lay in the River Medway, midway between Sheerness and Chatham and an old paddle wheel steamer used to take those wishing to go ashore twice a week. As Sheerness was a dead hole, all would go to Chatham. A trip to music hall was 6 pence with 3 pence for fish and chips. For those who could afford it 4 pence bought a night’s sleep in the Sailor’s Home.

HMS Pegasus on the Australian Station

After about three month’s shipkeeping, orders were received for Pegasus to proceed to join the Squadron in Australia. Things began to buzz then, loading ammunition, torpedoes, coal and naval stores. We left Sheerness after five days leave to commence the long journey. In the Bay of Biscay we ran into one of the most awful storms ever experienced when everyone was seasick, below decks were flooded, coal in bunkers shifted and we were hove to with our head into seas. The funnels were red hot and the seaboat was carried away. When I was lifebuoy sentry I used to fill my overcoat pockets with hard biscuits to chew when I went on watch. I tied myself to the mast with lashings and thought the end of world had come.

At last we entered Gibraltar and went alongside, where all the dock workers swarmed on board and helped to put things right. Later we left for Malta, coaled ship, had a run ashore and then off again to Port Said and Suez. With no refrigeration in those days we could only take limited supplies of fresh meat and vegetables; after this it was salt – salt beef and salt pork and biscuits. Anyhow, we all survived with a tot of rum every day and lime juice to prevent scurvy. At Aden we took on an upper deck cargo of coal. As the stock in the bunkers was used up, Stokers and Marines were employed refilling the bunkers from the deck cargo. It took us nine days to reach Colombo at an economical speed of 7 to 8 knots. Soon as we arrived, water barges came alongside and filled our tanks. The fresh water position on board had become very serious during the voyage with many stokers collapsing from heat exhaustion and we had to haul them up through the ash hoist to let them recover. Some of our Detachment was sent to the stokehold to fill their places.

After three days in Colombo we were off to Albany, West Australia with another upper deck cargo of coal. Here I was made an Officers Servant and had the task of looking after two Engineering Officers as a batman, waiting at table and cleaning the wardroom. Each of the Engineering Officers paid 5 shillings per month for my services. Their washing was the biggest problem since fresh water was scarce; only hip baths could be used in their cabins, their overalls were pretty black and could only be washed using their bath water. The water tanks were all locked up and only opened once a day by Tanky. We received a very warm welcome from the people in Albany and nearly everyone was invited to visit homes, which was a great relief to us sea wanderers. We were then off across a stormy Australian Bight to Melbourne. But we only had one day here before continuing our voyage to Sydney. Finally we arrived in Sydney early in 1905 after a voyage of 92 days. The detachment paraded many guards for VIPs including the Admiral. Rig of the day was white suits and helmets with puggarees. Some job pressing white suits, with no electric irons in those days, we managed with a rolling pin and a slat of wood about 3 inches wide and 3 foot long. Dockyard workers were soon on board taking stock of ship. We were then towed to Cockatoo Dock and there, the ship was thoroughly fumigated, as she was alive with cockroaches and rats mostly collected with provisions in Colombo. To clear the ship all hands were given two days shore leave. We stayed at ‘Johnny Shearston’s’ or to give it proper title Royal Naval House. Our amusement ashore was limited as we had very little money to spend. What a difference in Sydney then compared to today. Some other ships in Squadron in Farm Cove were HM Ships: Powerful (flagship), Challenger, Prometheus, Mildura, Psyche, Pioneer, Pyramus and Torch. All Royal Marines in harbour used to land once a week on the Domain or Cremorne Point for Battalion Drill.

After coaling and re-provisioning, we received orders to proceed to the New Hebrides and join the French ship La Meurthe in a visit to all islands on New Hebrides and New Caledonia. Some islands were fairly safe and officers used to go ashore and shoot wild pigs and with that we got an occasional bit of fresh pork. Other islands were very dangerous, the natives shooting on sight at strangers with bows and arrows. One visit we made was to Malekula Island where they had murdered the missionary. We were landed by cutter, had a Maxim gun in the bows and kept giving them bursts of fire and they took to the hills. We landed on the coral reef and waded ashore. I always remember this occasion as several of us stepped on the coral and it broke under our weight. I was one who went down; helmet floated off on top but managed to keep my rifle out of the water. No natives in sight so we burned their shacks, dug up the yams and killed the pigs, then returned on board. Some islands were quite friendly, they came out in their catamarans laden with limes, bananas, coconuts and would give a food supply for a shirt or a pair of pants. Next it was on to Noumea where eight natives that had been taken prisoner were landed but most had a good time trying French wines and chasing girls. Just out of town were the copper mines worked by convicts banished from France. We also visited the Society Islands, Friendly Islands, Tonga and Fiji. Much time was spent surveying the depths of water and tides, which was very monotonous.

After nine months of this wandering the Pacific we returned to Sydney. Here we received a refit and were then off to Hobart for the annual regatta, we all had a good time there visiting apple orchards and breweries. Back to Sydney again, replenished stores and then off to New Zealand. We rounded both North and South Islands and the small southern extremity of Stewart Island visiting all the important coastal towns. Everywhere people were very friendly indeed and made us really welcome. In Wellington Harbour, we lost our whaler with all hands in one of the severe storms that frequent these parts. Returned to Sydney and then went with the Squadron for Gunnery Exercises in Jervis Bay. The area was quite barren with little vegetation and no signs of houses, with only aborigines on the beaches. After about ten days we returned to Sydney where we were informed HMS Encounter (later HMAS) was on the way out to relieve us. This eventually took place and we commenced our homeward voyage duly arriving at Chatham late in 1907. After being marched to the Royal Marine Barracks for inspection we were given 28 days leave. I felt very rich having saved about £40 and gave my parents £10 pounds, lot of money in those days. I visited all my relations and friends who were all were anxious to hear about life ‘Down Under’.

On return to Barracks early 1908, we did refresher training and picked up one penny a day extra making my wages 6 shillings and 5 pence a week. Here I noticed in Divisional Orders, volunteers wanted for Probationary Clerk in the 1st Quarter Masters Stores Department that dealt with clothing, small arms and equipment. I was lucky enough to land the job and started on the following Monday. No more parade work for a time, found I had to keep ledgers of all stores in and out – both new and unserviceable. However I soon mastered the work, was confirmed in the job and promoted to Lance Corporal. On working my way up to 2nd Clerk the pay increased 6 pence a day. Then later saw in Orders, names required for Intelligence Clerk on the Commander-in-Chief’s staff in Sheerness. I managed to get this job and found it very interesting, distributing all confidential orders to Commanding Officers of ships and depots and attending the wants of the C-in-C, Admiral Sir Cecil Burney and his Chief of Staff, Commander Lake. The old Admiral was a bit crotchety, suffering from rheumatism, but I got on well with him and all those around. When the C-in-C embarked, I had to go with him in his flagship and we did many cruises around the British Isles. At this time I was promoted Corporal with another increase in pay. On the Admiral’s posting to a new command I went back to Barracks and returned to the 1st Quartermasters Department as 2nd Clerk

During my employment here I met my dear future wife. I had noticed her struggling up the steps to the top of a building with huge bundles of uniforms, serge tunics, tweed trousers and flannel shirts which she machine sewed. She was always neat and natty and very pretty but looked tired out. After passing inspection of her work, she would come down with another bundle for finishing. This happened three times a week. Gradually we passed the time of day and I found out that she was a widow with five children. Her husband who had been a Lance Sergeant had been an awful drunkard and never gave her any money. Her husband died of bowel cancer in 1909 and she now had to earn money to keep the home fires burning. As our friendship ripened I used to go out to Luton of an evening to help her sew buttons on garments and help look after her children. We would sit till about 9:30 pm and then I had to return to Barracks by 10:00 pm. Her little cottage on which the rent was 2 shillings and 6 pence per week was always clean and neat but she had to use oil lamps as no gas was laid on. I decided to propose and was accepted and we were duly married on 10 July 1910 at Ebenezer Church, Chatham. I was astonished at the crowd that turned up at the wedding. I had my best scarlet tunic on and new trousers; boots were polished like glass and Annie looked really lovely with a bouquet of roses. When we got home we found that the neighbours had laid on quite a repast, everyone so nice. That night we went to the seaside resort of Yarmouth for our honeymoon with the neighbours looking after the children for a week. My wages were now 17 shillings a week so we had to continue with the sewing and would sit up till 2 and 3 am in the morning to get bundles pressed and finished. The children were extremely good except the eldest boy who was always in scrapes, breaking windows, pinching fruit from greengrocers or fighting. We had an allotment and at weekends, we used to dig and plant vegetables to augment the larder. I still had to be in Barracks by 8:00 am each morning and took the horse tram, fare half penny, but walked home, usually carrying Annie’s bundle of work. We had a very happy life, never a cross word. I made the girls doll houses and the boys little hand trucks, bought them leaden soldiers and the girls dolls furniture to keep them quiet whilst we worked. A couple of rounds of bread and dripping when they got home from school and off they would troop until dinner was ready. Soon more children were coming along; first Reg followed by Marjorie and Cyril so we had a house full and had to move into a bigger house at 4 shillings and 6 pence per week. I can always look back on the last 52 years and say I had the dearest wife ever a man had.

I remained in the Quartermasters Department until late 1913. Then with war clouds on the horizon I was then embarked in HMS Lord Nelson, a 15-inch gun battleship with a mixed detachment of Royal Marine Artillery and Royal Marine Light Infantry. The ship was flagship of the Channel Fleet and again I was appointed Intelligence Clerk, a full time job and my own boss. Then in 1914, when war broke out and with Lord Nelson, Agamemnon, London, Albemarle, Topaze, Diamond, Formidable and Implacable we made a big show in the English Channel rounding up German sailing ships and taking them to Falmouth as prizes. Here I saw Formidable sunk by torpedoes from a German submarine rigged to look like a fishing trawler. Over 550 men drowned and only about 200 were saved. A general signal went up to proceed at full speed to Portland, except for the light cruisers Diamond and Topaze who were to stay to endeavour to pick up survivors. When we were in the vicinity of Dover, the Admiral used to have me landed over the stern walk on to the deck of a submarine, so that I could go to a hotel in Dover to take and collect mail from his wife.

With the Naval Brigade at Gallipoli and France

After a time a call was made for volunteers to join the Royal Marine Battalions then being formed. I put up my hand and was made Machine Gun Instructor (Maxim and Vickers), and was promoted Sergeant. At the training camp we were issued with khaki uniform and puttees. Very soon the Battalion was told to be ready for overseas service. We left Chatham Dockyard at midnight by train for Southampton, and my dear wife was there to see me off. As soon after we embarked in HMT Olympic we were underway for Gallipoli. Going through the Mediterranean we were advised of submarine attacks but the Captain did a marvellous job zig-zagging and we duly arrived safely at Mudros. Here the Royal Naval Division was formed consisting of six RNVR Battalions: Anson, Howe, Hood, Hawke, Drake and Nelson and two Royal Marine Battalions with Artillery, Signal, Veterinary, Supply and Medical Units to complete the Division of about 9,000 men which fought alongside the ANZAC Division. We duly landed at ‘X’ Beach, were murderously attacked and lost a vast number of men. How I avoided being hit I just don’t know, but there couldn’t have been one with my name on it. We dug ourselves in with entrenching tools and did our best against great odds. I lost most of my pals in this show. In the evacuation we got away by boats to Royal Navy ships and were conveyed to Marseilles. There we disembarked and were loaded into cattle trains all marked ‘10 Chevaux’ and did they stink. A very, very slow journey through France, with the only means of making tea was to get boiling water into our dixies from the locomotive. For tucker we had tins of bully beef and biscuits. We all slept on the wooden floors of trucks using our packs as pillows. When we arrived at the Front we were given a few days training and then found ourselves as reinforcements waiting to replace casualties in the trenches. My God, the slush and water and weather were just awful; anyhow we had to stick it for ten days until relieved by another Division; when we were sent out for five days rest and the rotation continued.

The next notable place that the Division was in action was Ypres; the weather was abominable, the worst ever. Trenches were flooded and it was bitterly cold with snow, sleet and hail. Our boots and puttees were saturated with mud and we stuck bully beef tins on the ground to tread on until duckboards arrived. In the meantime Fritz was giving us hell with his 8-inch shells and casualties were serious from flying shrapnel. From here we trudged to Metz and copped it hot. But promotion came along to those that survived and I was made Colour Sergeant, and then Quartermaster Sergeant. There was plenty of work awaiting me drawing provisions, stores, ammo, etc. from supply dumps but delivery was slowed as we only had ten horse drawn general service wagons.

From here we went to Neuville and Beaulucourt and later to Les Boeufs and did our turn in the lines until relieved. Then to Bargontin-Le-Grand, Fucourt, Albert, Mesnot, Martensort and Puchvilless. I tracked down my brother Tom at Tontencourt; he had been wounded three times in the hand by machinegun fire and was now back in the trenches serving with the 56th London Division. We had a happy reunion deep down in a dug-out, shared a bottle of plonk and off I had to go. Next on to Varennes and Lealerolas. After of plenty of action round Arras we were moved to Flanders fields in Belgium, near Poperinghe, it was Hell there. The Huns had flooded all the dykes and the place was a quagmire. Many of the younger men were drowned in the mud having decided to get off the duckboard track.

Up here I was twice mentioned in Dispatches and awards were signed by Winston Churchill. Then we were moved back to Albert, where it was a little quieter. Fritz used to come up in the middle of the night with an 8-inch gun on a train and let us have a few rounds. Here I was unfortunate with my transport. Fritz has observation Blimps up all day, with a crew supplied with powerful field glasses. They did the spotting and took information back to HQ of our movements and then we used to cop it. German planes also came over and dropped Belly Buster Bombs that exploded on hitting the ground. It was a difficult job keeping supplies up to troops in the front line but we managed. At one stage all my horses and some of my drivers were killed by aerial bombs. There was nothing we could do until sent a replacement mob of mules; the most obstinate creatures under the sun and, they did stink. After a while we managed to tame them down a bit and hitch them into the general service wagons, but they were always moody. At last we received a gift from Heaven in the form of eight AEC 4 ton motor trucks. These had to have chains on their wheels always to get through the slush but we still needed shovels when they got stuck. From here we went to the Somme again, Headoville, Martinsment, Polygon Wood and so on. Bitter fighting went on here and casualties were heavy. Not a tree left standing, all branches shot away, truly a dismal hole.

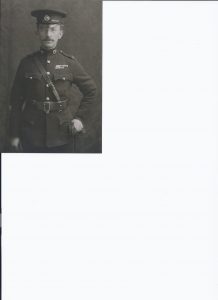

Now began the 1918 retreat. I had to load my eight trucks with all the paraphernalia of Divisional and Battalion HQ and hop it. All went well for a time, then we had to go through a sunken road dug by the Engineers. Fritz knew of it and shelled it unmercifully. We got about half way through and a shell lobbed in and No. 4 truck was set on fire. This contained all the office equipment and confidential documents of the Division. As there was no chance of saving it, we drained off some fuel and had a real blaze. Now what to do with wreckage was a problem. We got all drivers to bring tools from their trucks and hacked and bashed until we could pull what was left aside, sufficient to allow the other trucks to get through. We went helter skelter then to a rendezvous given by the Adjutant and QMG who had proceeded by car. Found him and all other Staff Officers, told them what had happened and to my surprise got complimented on the action taken. In a few days later news came out in Divisional Orders I had been awarded the Meritorious Service Medal. (Subsequently confirmed in London Gazette dated 17 January 1919 where His Majesty the King approved the Award of the Meritorious Service Medal to Sergeant G. W. Rayner in recognition of his services in France.)

The retreat got stopped and suddenly we were back in the line at the Hindenberg-Drount switch, not a Hun to be seen, they had disappeared and this was the beginning of the end. We explored the region and found hundreds of dead Germans stuck in the mud, a most grotesque sight. Wheels on their trucks and wagons were in some cases buried two feet deep. The Division was re-formed owing to the huge number of casualties we had sustained and to complete the Division the 1st Artists Rifles and the 3rd Bedfordshire Regiment was attached. Off we went in search of the wily Hun, knowing he would make a stand not far away on suitable ground. He certainly did but after bitter scrapping was routed and a large number of prisoners were taken. Thus ended four years of struggle and with the Armistice in November 1918 extra rum was served out to the troops and all began an endeavour to clean themselves up. I must mention here that I and another QM Sergeant heard some whisky was available at Doullens some 18 kilometres away, so we mounted horses, with two sugar bags each. My nag was an old London Cab Horse, steady but sure. We arrived safely, contacted the people who had the stuff, found it was 66 Francs per dozen. As my knowledge of French was pretty good we effected the purchase, put six bottles in each sugar bag behind our saddles and returned quite proud of ourselves. My word the boys did enjoy that drink – such a change from rum.

Life at home for the families was also difficult and many were to lose husbands and breadwinners and others having to contend with loved ones badly wounded. Annie recalls German Zeppelin airships cruising over the port of Chatham dropping bombs on the naval base at night. Searchlights sometimes illuminated these eerie large shadowy objects making them targets for the few anti-aircraft guns available in England but they still managed to drop their bombs. Another memory was of returning older soldiers who became known as the Old Contemptibles. When they returned many were worn out and in a pitiful state. They drew the utmost sympathy from the townspeople of Chatham as they marched to their barracks and many taken to hospitals.

Twice during the War, I was able to get a few days leave. We travelled light, tin helmet, respirator and waist belt with haversack and water bottle. On one occasion I took half a water bottle of rum with me. When I got home just hung it on a hook behind the door, didn’t care for rum myself. Next day Sonny (Arthur), the eldest boy, nosey like, took a swig of the rum, nearly killed him, he never touched it again. Found everything at home perfect and we had a lovely seven days. Mum went to Victoria Station from Chatham to see me off. Gradually the Royal Naval Division was withdrawn, only a token number of troops remained in case of further outbreaks. We entrained for Boulogne, found ships waiting to take us across the Channel to Southampton; here we were split up to go by train to our respective Divisional Headquarters of Chatham, Portsmouth, Plymouth and Deal. After replenishing our kits and getting onto blue uniforms once more, the Division was ordered to assemble at Horse Guards Parade, London, for inspection by the Prince of Wales. A weary mob of troops and only the remnants of what had been a magnificent fighting force.

After this parade I was instructed to report to Royal Marine HQ at 23 Carlton House Terrace, London for duty on the Quartermasters side for stores of all classes. After leave I duly reported and found the work most interesting, was well received by staff from Commandant General downwards. For a time main job was the collection and disposal of all war stores, a colossal job. Most were collected in dumps and sold by auction to the Jewish fraternity. At the same time work of reequipping the Corps with modern equipment. Restoration of blue uniforms and full dress (scarlet tunics with white facings), new type helmets and reduction of the number of suits of khaki per man. Had to prepare estimates of cost of this for 12,000 Officers and men and it meant some work. Most of the garments were made in the tailor shops at Chatham, Portsmouth, Plymouth and Deal. Finishing was still carried out by Marine wives. During my daily journey to London from Chatham (32 miles each way) I had to catch an early train to reach my office by 9 am. I made friends with a fellow passenger who turned out to be an official of the London County Council housing branch. He promised to get me a house on the Norbury Estate, near Croydon. This he eventually did, one brand new with four bedrooms, at 12 shillings and 6 pence per week, a lot for us, but with the one shilling per day London Allowance we managed. I used to catch the bus at Norbury Station, buying a workman’s ticket at 6 pence return which was a big saving against the rail fare from Chatham. We moved up and entered the children in the local Council School.

Whilst living here my younger brother Reginald (Reg) came to live with us. But he was restless and decided he wanted to go to Australia under a migration scheme then being offered to youngsters (the Big Brother scheme aimed at bringing youths from Britain to work on Australian outback farms began in 1924) to work as trainees on farms. So straight from school Reg was off with many others and wound up with another boy on a farm near Cowra in New South Wales.

My uniform being on General Staff was quite a smart affair, tartan tunic with gilt buttons, ornaments and numerals, large mounted gold crown for left forearm. Tartan cloth trousers with red stripes for summer wear and heavy cloth for winter. Cap with peak and scarlet band. Boots specially made in shoemakers shop and the last was retained by the Master Shoemaker. I always carried a smart cane of polished Blackwood surmounted by the Corps crest. Used to feel quite proud of myself in those days. Work at office kept us all very busy everyday. Mum provided my lunches, usually a small meat pie and a fruit tart with a walk in Hyde Park for a few minutes at lunch time. All this continued until 1925 when I was due for promotion but Parliament formed an Economy Committee on the Services headed by Sir Eric Geddes with instructions to reduce expenditure. Our staff was sadly reduced with two of us senior men having to go, so that was that. The Commandant General offered me the Dockyard Police at Grimsby or the Recruiting Staff. I wasn’t struck on either offers, but accepted the Recruiting job. I was then appointed to East London area but soon found there was a slump in Recruiting and had nothing to do.

Return Down Under

I decided to get in touch with my old mate Patrick (Patsy) Hayes who served with me in HMS Pegasus and was now living in Sydney. He had joined the AIF and we met in France, and again at Wandsworth where he was in hospital after having been gassed. He had risen to the rank of Major in the legendary 14th Battalion AIF. After the war he had joined the Public Service and worked in the Naval Stores Depot at Garden Island. He cabled me to come out to Australia and had a job waiting for me. I got busy, resigned from the Recruiting Staff, got through all the usual formalities and sailed in RMS Ormonde. Duly arrived in Sydney in late 1925, on a Thursday, and started work at Garden Island on the Monday in the Torpedo Workshop. From there I was later moved to the Gun Mounting Department and then to the Engineer Managers Department as curator of drawings with hundreds of pigeon holes containing drawings of all parts of ships. At the time HMAS Albatross was being built and I was entrusted with keeping a register of all drawings so that I knew exactly where one was if required. I took all the blue prints off the machine after the draughtsmen had completed them. I remember one time when the machine broke down and I fiddled with it and got a nasty electric shock which knocked me across the office.

Had arranged for Mum and children to come out to Australia, they came on RMS Osterley. I had arranged a cottage and furnished it, with help of Patsy Hayes, at Marrickville. We found rent too dear on my wages of £4 a week so got a place at Greenacre near Bankstown but the journey to Garden Island was much longer and more expensive. At this time I went to Cowra to see Reg where he was working as a farmhand and saw him ploughing with a team of horses. I stayed at the farm a couple of days but the conditions for the youngsters were quite primitive and they were little more than poorly paid labourers. With the help of my new employers Reg was interviewed and accepted for an engineering apprenticeship at Garden Island Dockyard.

We were doing quite well until suddenly a blow came in the 1928 Great Depression. The Secretary of the RSL found a clause in the Act for Employment of Ex-Service men, that men from UK were not entitled to any preference over Australian personnel unless living in Australia 12 months before 1914. This was a cause of great concern as 43 of us at Garden Island were affected. I helped form a deputation of ex-servicemen and we put our case to the Captain-in-Charge of Garden Island, the Admiral, and later the Governor General, Sir Isaac Isaacs but they all said the Act must be observed. With that we all had to go, all of us being time serving men of the Royal Marines and Royal Navy who had been encouraged to come to Australia. Fortunately I had a great friend in Commander Leo Quick, RAN who commanded the Naval Depot at Rushcutters Bay. He was greatly interested in the Ex-Servicemen’s Association and appreciated the amount of work I had done for all its members. He told me he would help find me employment.

Sometime later a letter arrived from Commander Quick telling me to report to Colonel Alfred Spain, the Chairman of the Taronga Park Trust. I spruced myself up and duly reported for a long and difficult interview for a vacancy at Athol Gardens as Caretaker and Ranger. I never thought I would make the grade but was eventually selected from over 100 applicants. This meant another move for our family to quarters at Athol, such as they were. Jobs were very scarce in 1929 as the worldwide depression had created vast unemployment with men having to recourse suburban soup kitchens for feeding families. While the North Shore was relatively prosperous and families with means could ride out the Depression there were others who were reduced to living in humpies and caves that surrounded the foreshore.

But life goes on and must have improved for Reg as after he finished his apprenticeship at Garden Island in July 1934 he was accepted as an Acting Engineering Artificer in the RAN. Reg was to serve with the navy throughout WW II and was a Chief ERA in HMAS Australia during the Pacific campaign.

The original manuscript finishes here and another grandson Stephen Rayner has provided information to complete this story.

Return to the Colours

In 1939 with war again looming George was now aged 53 and was well aware that there could be a need for experienced ex-Navy and ex-Marines. He volunteered for service well before the declaration of war and the mobilisation of Reserves and with a few other seasoned veterans was sent to HMAS Cerberus to prepare for an influx of new recruits. He was given the rank of Warrant Officer Class 2, RANVR and was responsible for re-training many of those who had volunteered to rejoin the colours which included about 40 ex-Royal Marines who were mostly to become parade ground instructors, helping getting into shape the large number of new recruits flooding into the navy. One of the ironies of war was at to play out at Cerberus in late 1939 when three Rayners were serving there. Newly arrived George and his younger brother Reg then qualifying as a Chief Engineering Artificer and George’s son Cyril who had been a Sea Scout and later joined the RANR was mobilised for his initial training. All three were to serve in the RAN throughout WW II

George remained in the Navy throughout the war and in 1944 was posted to HMAS Melville to manage naval ammunition supply stocks which had been dispersed in dumps in the Northern Territory. In November 1945 he was posted home to HMAS Rushcutter and their demobilised. Afterwards George and Annie retired into a home unit in Musgrave Street, Mosman where he died on 18 July 1962 with Annie dying a year later on 22 December 1963. Brother Reg resigned from the RAN in 1946 and started a small ship repair business ‘Fleet Forge’ in Melbourne. Reg passed over the bar in 1995. Young Cyril, now 94 years of age, lives in Sydney with his son Stephen.