- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - general, Biographies and personal histories, Garden Island

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2013 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Ian Thomson

The author provides us with a delightful vignette of life as a dockyard apprentice. We should also remember that workers at Garden Island Dockyard were employed by the then Department of the Navy. After leaving Garden Island Ian entered the commercial world working in the aluminium industry. These days in retirement he re-uses some of those old skills learnt as an apprentice in repairing and polishing antique furniture and making things for grandchildren.

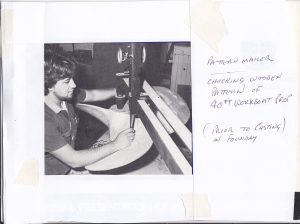

It was just a week before Christmas 1953 when I received with great excitement a formal letter from The Department of the Navy advising me that I had been accepted as an apprentice patternmaker with a three month probationary period. I was to report to the Superintendent of Apprentices at 7.30am on January 4 the following year. I had completed a year at Sydney Technical College, Ultimo doing a pre-apprenticeship course in patternmaking and had applied for a number of jobs at various companies but Garden Island was the plum. None of the other positions had the same variety of work that Garden Island offered.

From Day One my excitement at being at a naval dockyard was almost over-whelming. All around the island were these fascinating ships of war; destroyers, frigates, corvettes and sloops. Opposite Garden Island, at Athol Bay, lay a heavy cruiser named HMAS Shropshire looking rather neglected. She and a few other lesser ships were a part of what was known as the ‘mothball fleet’. I thought at the time that the name Shropshire did not sound very Australian. I was subsequently told that this proud old lady had seen many years of service, first with the Royal Navy and then handed over to the Australian Navy in 1942 as a replacement for HMAS Canberra lost in action in the Pacific. A few months later, in October 1954, Shropshire was towed out through the Heads on its way to be cut up for scrap; an ignominious end to a proud old ship of war.

Living out in the western suburbs of Sydney, I had to leave home before 6am, catch the train to St. James Station then a double-decker bus from Queens Square to the Garden Island terminus. As we filed off the bus I had to pick up a brass disc with my allocated number 398 stamped on the face. It was then placed on a numbered board in the dockyard machine shop for the timekeeper to check on latecomers or absentees. Misuse of anyone else’s disc resulted in a severe reprimand.

‘Smoko’

Work began at 7.30am and we were expected to be at our benches ready to start when the whistle blew. At 9 o’clock we stopped for morning tea or smoko time as it was called in those unenlightened years, (although smoking was strictly forbidden in the pattern shop at any time). During the

morning tea break we could stop work for ten minutes but sitting down was not permitted. This was later relaxed and we were allowed to sit on our bench. At 12 noon, a whistle blew for a forty minute lunch break and the final whistle went at 4.10pm after a leeway of ten minutes to allow for packing away tools and cleaning up. During the forty minute lunch break, we would either play cards, darts or table tennis. Alternatively, we could snooze or walk around the island if it was a nice day. On one occasion we made three-pronged spears and tried our hands at spear fishing from the boat pound. As there were usually a number of more serious handline fishermen at the same places, we were quickly shooed away by them, calling us ‘pesky little so and sos’ and ‘go away and stop disturbing the fish’. These requests were normally expressed with a little more vigour and colour.

There were only ever three apprentice patternmakers at any one time. George Robertson was in his second year and Dick Bentley was in his fourth year. I was not to meet Dick for almost three months, until he had finished his compulsory National Service training in the army. The Korean War had finished some months before so he did not experience active service. The shop foreman was Ray Bench, a stern but fair minded boss, and Laurie Young the leading hand. After my probationary period was up,Laurie took me over to the stores building (built in 1893) to select my basic set of tools. My weekly pay packet, in my first year, was four pounds, out of this two shillings was taken for tax.

The pattern shop was located on the second floor of the machine shop building on the eastern side overlooking the clock tower office building directly opposite. This building housed the administration staff as well as the drawing office. One advantage of this is that we were provided with a wonderful view of the office girls as they arrived for work from about 8:45 on. At this time of day there always seemed to be a need for some work to be carried out near the window. Concentration on the job was at a low point until 9am when all the girls were inside the office and out of sight.

Striped paint

Lots of things had to be learnt by a first year apprentice; not the least was how to avoid being taken as a sucker. The novice apprentice would be sent down to the engineering store for such things as a left handed hammer or a can of striped paint. To be sent to the store for a long weight would, to the unwary, result in one. On one occasion, I was given the task of going to the canteen for the morning tea break and one tradesman asked me to get him a ‘randy tart’. As a rather naïve 16 year old I didn’t know what this meant but felt sure there was a trap in there somewhere.

When things were quiet in the shop, permission was covertly given to make foreign orders or ‘rabbits’ as they were known on the island. This term apparently came over with dockyard workers from England. We apprentices were particularly encouraged to make tool boxes necessary to keep things tidy. Specialised tools not commercially available, or too expensive, had to be made. Wood turning tools of various shapes were made from old metal working files ground down on a surface grinder by a friend in the machine shop. It was handy to develop friendships in other trades so that favours could be reciprocated. Diversity of trades was a great blessing. Welders and blacksmiths came in handy from time to time. The foundry was used to cast tools such as special purpose planes. The electricians in the building next door were useful because they had engraving machines which could give a professional appearance to proof of ownership by having your name tastefully engraved.

During my second year a general strike occurred, dragging on for six weeks. All the men were out. The only people still attending work were office staff, foremen and apprentices. As the work in progress gradually dried up, our foreman, Ray, found it increasingly more difficult to find work for idle hands so we apprentices were actually encouraged in making ‘rabbits’ on the basis that it was the lesser of two evils. A number of tradesmen left Garden Island during this period to find other work to support their families. One of the projects I worked on to keep myself busy was a wooden lunch box. I spent many hours making this beautiful French polished box with dovetailed corners, hinged lid and brass clasp. To complete this work of art I used a contrasting timber to inlay the word ‘LUNCH’. Some years later after I had married, my wife, rather cheekily I thought, asked me why it was necessary to have ‘LUNCH’ on the lid! Would I have not known otherwise that my sandwiches were inside?

Severe penalties

The most difficult thing about the completed ‘rabbit’ was getting it off the island. The Naval Dockyard Police had the job of security. On leaving work for home in the evening the police did random checks of bags and severe penalties, including dismissal, were meted out to any who were unlucky enough to be caught taking things out without authorisation, particularly if the goods were obviously government property. One way of getting around this was to bring in something from home that could be loosely described as whatever it was you wanted to take out, obtain a pass on entry and hope that the description on the form was worded as vaguely as possible.

Trafalgar Day 1955

1955 was a big year for the Navy. The Battle of Trafalgar had been won by Lord Nelson for the British 150 years earlier, and Trafalgar Day was celebrated at Garden Island in October with an open day for the public. October 21st was the day of commemoration which this year fell on a Friday. Preparations began some time before with the cleaning of places never before cleaned. Repairs and painting were carried out all over the Island. Tradesmen and apprentices were to be in their newest or cleanest overalls. Trafalgar Day was a beautiful sunny day with crowds wandering over the island inspecting various ships moored alongside or going through the different workshops seeing how each trade functioned. In the pattern shop, the most interesting patterns were brought out from the pattern store for display. Easily recognisable items such as propellers, fire hose fittings, ship’s badges, etc. were placed on a number of work benches. A great day was had by visitors and workers alike.

When I first began my apprenticeship Jackie Hoare, one of the labourers, took me under his wing. He was a member of the Ironworkers Association or IWA for short. All labourers working in the engineering department were required to be members of this union. Jackie had some amazing stories to tell including his memory of the British navy when sailors still wore sennit or straw hats. These hats were still being worn by some British sailors up until the First World War. One of the main things Jackie taught me was how to french polish and although ever only an amateur, the skill remained as a very useful talent well into my retirement years.

The Foreman’s lunch

The pattern shop supported two IWA labourers; their jobs included sweeping the floors, running errands and generally helping the tradesmen when necessary. One of the jobs was to bring the foreman his lunch which was either kept in the refrigerator downstairs in the engineering shop or placed in a small electric oven for heating. We all considered this to be ‘sucking up’ as it was not deemed to be compulsory. Ray, the foreman, would bring in a stew from home in an aluminium bowl with a lid held in place by three clips which would undo when the central knob was turned. On one occasion, Jimmy Ross, one of the labourers, was carrying this heated up bowl to the boss holding it by the knob when it suddenly released and fell upside down with the entire contents spilling on to the floor. With quick presence of mind, Jimmy scraped the stew back into the bowl making sure that not too many wood shavings and bits of sawdust were included and continued on to Ray’s office with lunch. Ray cleaned up his bowl without noticing anything amiss but must have wondered why there were so many faces at the window of his office, all watching his every mouthful with great anticipation.

Another of the IWA’s functions was to fill up the billies with hot water for morning tea and lunch. This was achieved by carrying all the billy-cans with the wire handles in a slotted piece of timber. Each individual brought in his own tea and sugar. The hot water was available downstairs in the machine shop and the IWA would go and line up with others ten minutes before it was required. If, for some reason, the labourer was absent, it was left to the youngest apprentice to carry out this very important task. A few years later, the pattern shop acquired its own hot water urn and we were able to make our own tea when required. In the 1950s coffee was not the popular drink it is today.

Although the IWA labourers were responsible for most of the menial tasks of the pattern shop, it was the first year apprentice who had responsibilities related to the trade. These included mixing the paint for the finished pattern, making sure the glue heater was on and did not dry out, tailing off when the tradesmen were feeding timber through the circular saw or the thicknesser. They also carried out the duties of the IWA men when they were absent or ‘taking a sickie’ as it was known.

Glue and its problems

The glue pot was a very important responsibility of the first year apprentice. Aquadhere, or white PVC glue, was not introduced to the pattern shop until the late 1950s and the original glue until that time was animal glue. This came in granules which were dissolved in water and heated to a constant temperature of around 40 deg. F to stay liquid.

Glue consistency had to be a balance between too thick and too runny. The glue pot was suspended in an urn full of water which was constantly topped up as it evaporated. The urn had a safety switch that turned off if the water ran out but by then it was too late and the glue would start to overheat. When this happened everyone in the shop immediately held their noses and complained loudly and coarsely. The apprentice responsible for maintaining the water level would suffer a tirade of obscene verbal abuse from all within smelling range.

Paint preparation was another important task. The finished pattern was given a smooth finish to allow easy withdrawal from the sand mould in the foundry. Paint colours were important. Black was used when the casting was to be a ferrous metal, yellow was for brass alloys or aluminium and red signified a surface which was to be machine finished in some way. The paints were shellac based dissolved in methylated spirits, to allow for quick drying. After the pattern had been moulded and cast it was returned to the pattern shop, catalogued and placed in the pattern store. I was saddened to hear some fifty years later, that all those patterns were eventually removed and burnt. The reason given for the destruction was that they were a fire hazard. This was probably true as the pattern store was located directly above the foundry. All the same, it is a pity some of those patterns could have been retained for historical purposes.

When I reached my second year, Dick Bentley had by now become a tradesman and so a new apprentice started in January 1955. This was a significant event for me; no longer was I to be at the very bottom of the hierarchal pecking order. After twelve months on the bottom rung I was to move up to a position of greater responsibility. At last there was going to be someone lower on the food chain than me. I could teach the new bloke all those onerous tasks that I had been doing and now concentrate on improving my trade skills. Ray Bench escorted the new boy into the shop and introduced him all around. Graeme was a gangly, shy and pimply faced kid looking quite out of place in his blue bib and brace overalls with all his co-workers in white.

It was probably because I had done a pre-apprenticeship course in patternmaking at Sydney Technical College that I had a head start when I began at Garden Island. Graeme apparently had no idea what a patternmaker did. I felt very superior to this new beginner, passing over to him all those first year responsibilities teaching him the lowly tasks of mixing paint and keeping the gluepot topped with water and so on. Fortunately, my pomposity was short lived and we became good friends. In my seven years at Garden Island only two apprentices followed me into the trade of patternmaking. Roy Hawkins began the trade in my final year.

My family moved to North Sydney in February 1956 and there was now no need to leave so early. Going to work by ferry was much better and far more interesting. I would stand at the front door of our house overlooking Berrys Bay and watch for Charlie Rosman’s ferry La Radar to appear around the point of Balls Head. As soon as it was sighted I would walk to the Lavender Bay ferry wharf, leaving home an hour later than while living in Sydney’s western suburbs.

Ferries and Fog

The ferry trip to Garden Island was never boring; there was always something of interest to see on the harbour. There were times when we would be escorted between Jeffery Street wharf and Garden Island by a pair of dolphins. The most exciting trips were during heavy fog. While government ferries stopped running, Charlie Rosman did not. I don’t know whether Charlie had a compass in the cab or not but we apprentices up in the bow would watch out for whatever we could see ahead and yell like mad if something was sighted. Once or twice we overshot the Island and nearly landed at Mrs. Macquarie’s Chair. Mostly, Charlie was right on target. On one occasion in 1955, before my move to North Sydney, I was told of a Manly ferry running aground in thick fog near Bradleys Head. Charlie, with his unerring ability to navigate in fog, pulled La Radar alongside the stricken ferry and was able to transfer the passengers safely to Circular Quay.

At the end of the working day, the various wood-working machines were covered over with canvas covers meticulously made by the sail makers, thus preventing, or at least reducing, the effect of salt air rusting the surfaces. These machines included the bandsaw, thicknesser, planer – or jointer as it was called – circular saw, lathes and sanding disc. When I first started, the large lathe and sandstone grinding wheel were still being run by a large leather belt on an overhead pulley. In 1957 a vacuum dust extractor was installed which took away much of the dust and shavings from the bandsaw, thicknesser and planer. This reduced a lot of the sweeping being done by the labourers. The shavings were collected in large hessian bags and sent away somewhere for recycling.

Outside the heavy double sliding doors of the pattern shop was a balcony approximately one and a half metres deep and three metres wide. Around this platform was a removable chain fence. To the side was a swing out arm with a steel cable and pulley which could be lowered to the ground five or six metres below. This hand-operated hoist was used mainly to bring up the timber planks necessary for making patterns, or models as they were sometimes called. The whole operation of bringing up timber from the store involved the services of at least three men; one man on the ground to secure the cable around the planks, one man on the balcony to guide the timber as it came up and one man to turn the cranked handle of the crane. Sometimes it was necessary to have more. The whole operation was very dangerous and had to be undertaken with great care.

In 1956, I submitted a suggestion to management that the man on the balcony guiding the cable should be fitted with a safety harness. Of necessity, the chain rails around the platform had to be removed and the risk of toppling over the edge was quite high. I was rewarded for my suggestion with a gift of two pounds ($4.00) which at the time was equivalent to about one day’s pay for an apprentice. The harness was installed and a short time later an electric hoist replaced the old hand operated one, making things easier and further reducing the risk of injury.

‘Loveable old grouch’

One of the most senior tradesmen was Ken Ogden. Ken was a loveable old grouch and was probably the first person I had met who had gone through a divorce. Ken was always struggling to make ends meet and would grab any bit of overtime. He would volunteer for whatever came along. He could make a pencil, a razor blade or cake of soap last far longer than anyone else, even picking up someone else’s discard. ‘Any port in a storm’ was a favourite expression of his. He would make do with whatever was available. During the winter months, Ken would cut up and take home pieces of scrap wood for use in his fireplace.

One of Ken’s pet hates was to hear someone singing or whistling either Danny Boy or Come back to Sorrento. If he heard any rendition of either of these tunes his loud caustic remarks would burn the ears off the by now embarrassed culprit. Radios were not permitted in the shop so whistling or singing were acceptable forms of self entertainment. Ken’s funeral in 1967 was the last contact I had with my patternmaking workmates as a group.

Quiet contemplation

The nearest toilet to the pattern shop was located some 50 or 60 metres away opposite the Boatshed and whenever a break was required it was a pleasant walk on a sunny day. There were two or three smokers in the pattern shop and as smoking was strictly forbidden, then a walk to the toilet was a regular event. The toilet block had quite a large catchment area of clients. It was used not only by the machine shop workers but also the boat builders, various stores and other nearby workshops. There were often times when a queue would form for cubicle use. On one side was a urinal and on the opposite side were six cubicles with Vacant/Engaged locks on the doors. As this was a place for quiet contemplation for smokers, or an opportunity to read one of the latest men’s magazines or paperback, queues were quite common. This dilemma was handled in a number of ways. Firstly, if the intended user was not desperate he would do a u-turn and return later. Next, if one person was waiting then the second person to arrive would converse loudly to let the incumbents know that more than one person was in some need. As more arrived and the queue got longer, the conversation would increase in volume and sarcasm directed at the silent inmates. If there was still no sound of toilets flushing the last resort was to turn off the lights. Finally, one by one the occupants would complete their business and sheepishly make an exit.

Occasionally, some of the occupants of these cubicles would run out of reading material and let their creative minds run into artistic or literary mode. The partitions were made of terrazzo and the wooden doors painted in battleship grey, excellent mediums for writing in pencil or biro. Consequently, the walls and backs of doors were very soon covered with all sorts of graffiti; much of it very clever, some of it rather crude. All of it made interesting reading if you failed to bring your own.

Towards the end of the year in 1957, I was invited to participate in the sea trials of HMAS Quiberon, which had been built in England. She served in various parts of the world during WW II and after. From 1950 to 1957 she was converted from a destroyer to a fast anti-submarine frigate and it was during her sea trials prior to commissioning that I had the thrill of participating as an observer with no onboard duties.

It was on one of those beautiful December days with the clear blue water reflecting a cloudless sky that we steamed up and down the coast from Port Hacking to Broken Bay. The sea was calm with just a slight swell but when we came to the extremities of the run a high speed turn would cause the ship to heel so that we idle passengers who had been enjoying the coastal views had to hang on as the water almost reached the gunwales. Bread rolls and salad were served from the galley at lunch and eaten on the sunny deck while the trials continued until we finally berthed back at Garden Island in the late afternoon.

I completed my five-year apprenticeship at Garden Island on 5th January 1959 and continued as a tradesman for another two years. During my final year Ray Bench retired and Arthur Myatt became foreman. Dick Bentley had moved to being charge hand and it looked like quite a few years ahead before either position would open up to me. I left Garden Island for a career in the aluminium industry but my eight years at the Naval Dockyard left me with wonderful memories of great friends and with a raft of lifetime skills.

Editor: Our records show a list of those completing apprenticeships at Garden Island Dockyard in 1959, with 56 apprentices completng training covering 12 trades.