- Author

- Turner, Mike

- Subjects

- Naval technology, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2016 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Mike Turner

Awards for Rendering Mines Safe (RMS) operations give some indication of the hazards involved. The George Cross (GC) was awarded four times and the George Medal (GM) nine times to RAN personnel for bravery in World War II. Apart from a GM for a hazardous diving operation all were for RMS operations. The RAN lost three personnel during RMS operations, and another four were lost when HMAS Warrnambool was sunk by a mine whilst sweeping at the Great Barrier Reef. There were also many ‘close calls’ both at sea and ashore.

RMS operations in Europe

German aerial ground mines were fitted with at least one anti-recovery device, and there was always one in the bomb fuse. A mine detonated about 17 seconds after it was laid on land or in water less than 3.7 m deep. A fuse could jam and later operate if it was disturbed. An RMS officer had no chance of escape when a bomb fuse ran in unfavourable circumstances, for example in a shaft or deep mud. Lieutenant J.S. Kessack GM, RANVR was killed in such circumstances in England on 27 June 1941.

The German GG bomb-mine ‘George’ was developed by the Luftwaffe to reduce the probability of mine recovery by:

1 Decreasing the probability of laying above the low water mark by eliminating the parachute that caused drift for earlier mines.

2 Fitting a fool-proof anti-removal device that detonated the mine charge during RMS operations in daylight.

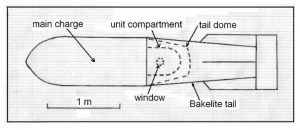

‘George’ was unique in that there was no external access to the primer and detonator, and they could only be accessed by removing the tail dome. When the tail dome was removed it exposed selenium photo-electric cells under windows in the unit compartment, and the mine could only be rendered safe at night.

All four GC winners had ‘close calls’ as follows:

On the night of 23/24 May 1941 Lieutenant Hugh Syme RANVR (subsequently GC GM*) was rendering safe a live ‘George’ near the RAF Base, Pembroke Dock. He had just removed the tail dome when lightning suddenly struck very close to him. A sixty-second electrical storm seemed like an eternity whilst he covered the two cell windows with his hands. Fortunately Syme had reacted very quickly and the cells required several seconds of light to operate.

Lieutenant Leon Goldsworthy RANVR (subsequently DSC, GC, GM) rendered safe a mine in Milford Sound in the UK. When the mine was examined it was discovered that it was a live acoustic mine that would have detonated but for an errant chip of insulating varnish on the electrical firing contacts.

Lieutenant John Mould RANVR (subsequently GC, GM) was working on a mine in England, and realised that he would need a longer keeper-ring spanner which was back in the car. After retrieving the spanner he returned along a hedge-lined lane. The mine detonated when Mould was 27 m abeam of the mine and only 5 m from the gap in the life-saving hedge.

On 9 May 1945 at Ubersee Haven, Bremen, Lieutenant Gosse RANVR was the first to render safe an armed pressure mine, a German GD mine. In German mines water pressure overcame a safety spring to move the primer down a tube to surround the detonator. With some difficulty he removed the primer, but did not want to disturb the detonator lest the ingress of water fired the mine. Gosse was just about to leave the mine when the detonator fired. This was due to water leaking past the detonator after the primer was removed, and causing an anti-recovery hydrostatic switch to function. Gosse rendered safe two more pressure mines underwater, and each time the detonator fired (as he expected) 10 to 30 minutes after he commenced rendering the mine safe. He was awarded the GC for these operations.

RMS operations in Australia

The German raider Pinguin laid GY* mines near Adelaide in November 1940. On 12 July 1941 an armed and drifting GY* mine was found by a fisherman in Rivoli Bay near Robe, SA.He attached a line toone of itshorns and towed it to a beach. An RMS Party arrived from HMAS Torrens, comprising Lieutenant Commander Arthur Greening RAN, Able Seaman William Danswan, RAN and Able Seaman Thomas Todd, RANR. On 14 July a demolition charge was placed on the mine, and a cable run to an electric exploder. After a misfire Todd and Danswan went back to check the mine. Both sailors were killed when the mine detonated, probably due to a wave rolling the mine and breaking a horn. They are thought to be the first Australian casualties on Australian soil during this war.

A sailor named Thomson in a Queensland RMS Unit set out on horseback from Combe Hill on a 25 km journey to Roundstone Beach, escorted by the local policeman and a fisherman who had located a mine-like object. The policeman was armed with a rifle for protection against a notorious dog-killing boar ‘Bloody Bill’. Thomson identified the object as a German GY* mine, noted the mine’s details and gave his notes to his two companions. They walked down the beach to a safe location.

‘Bloody Bill’ emerged from the bush before Thomson could work on the mine. The policeman’s rifle jammed as he took a second shot, and Thomson’s two companions dashed further down the beach. After Thomson had swum out to sea at ‘homeward bounders’ speed for about 50 m he was dazed by an explosion. ‘Bloody Bill’ had charged Thomson’s shirt flapping on a horn. A large crater marked the spot where the mine, boar and Thomson’s RMS tool kit disappeared. The three horses had bolted, and the party trekked back to Combe Hill. A highly amused NOIC ordered a survey note be prepared in respect of the loss of the RMS tool kit, and to show it as ‘Lost by enemy action at Roundstone Beach’.

Risk to minesweepers when sweeping moored mines

Moored mines sank at least ten Allied minesweepers whilst sweeping in the Pacific. The first minesweeper sunk in the Pacific was HMNZS Puriri, which was sunk near Auckland on 14 May 1941 whilst sweeping German GY* mines laid by the German raider Orion. The US Navy lost at least eight minesweepers to moored mines whilst sweeping.

RAN Australian Minesweepers (AMS, aka Bathurst class corvettes) used Mk 1 single Oropesa wire sweeps for clearance sweeping. If neither the serrated sweep wire nor the static end cutter severed a mooring, the mine could become fouled in the otter. The combination of a moored mine and a Mk 1 otter was negatively buoyant. A fouled mine was only sighted when the otter arrived at the stern during the final phase of sweep recovery, generally at dusk. The mine could still be armed due to marine growth not allowing the mooring spindle to retract and open the arming switch when the mooring was severed. A fouled mine was a vivid memory to many.

HMAS Burnie was working up with double Oropesa in Investigator Strait, South Australia in May 1941 prior to departing for Singapore. Her kite was recovered at dusk, and when it was only 3 m from the stern a mine was sighted draped over the kite. Lieutenant Commander Bert Dechaineux (a lieutenant at the time) recalled:

Veer! Veer! Veer! We steamed around all night with the kite ‘a long way astern’ and on recovery next morning no sign of the mine … The chilling factor was that Burnie must have steamed directly over the mine for it to be hooked on the kite instead of picking up the sweep wire on either side. Tick off one of Bert’s 9 lives!

After sweeping Backstairs Passage near Adelaide the Grimsby class sloop HMAS Warrego was recovering her sweeps at dusk with a following sea. Martin Howley (ex-Warrego) recalled:

It was discovered a bloody great black mine was entwined on the cutting cable, about 30 feet [9 m] from the stern … [and the mine] which had tangled in our gear was lifted on a ‘greenie’ and the base of it thumped our stern, guess we were lucky that day.

Later Warregowas at the invasion of Balikpapan in 1945 in a survey role, and was at anchor. A most unusual outcome of a mine fouling a sweep is recalled by Don McIntyre (ex- Warrego) as being ‘a lot more exciting’ than the following extract from Warrego’s ROP for July 1945:

At 1349 on the 6th YMS 97 [USN Yard Minesweeper] while sweeping in the vicinity fouled a mine which she dragged onto Warrego’s cable and it exploded about 20 ft. [6 m] from the ship’s bow. The ship was deluged from stem to stern but no damage was revealed except for slight denting to the port bow.

After two mines detonated in HMAS Kalgoorlie’s sweep near Thursday Island on 23 July 1944 she hove in the otter and the otter jumped out of the water when it was about 22 m astern. A mine detonated when the otter re-entered the water and the ship was completely drenched in water. The float was nowhere to be seen and the otter resembled hoop-iron. There was some damage to electrical equipment and a broken pipe in the engine room, but this damage was quickly repaired. Kalgoorlie reported at the end of sweeping a few rivets had been made loose by nearby explosions during the sweeping operations, but were not serious.

Navigation at the Great Barrier Reef was hampered by the lack of well defined navigation references. A discrepancy between the plots by the minelayer HMAS Bungaree and the AMS HMAS Pirier esulted in Pirie inadvertently transiting the COASTER minefield in August 1944. A Mk XIV mine was seen nestling alongside Pirie’s port side by a leading stoker throwing his slops over the side, and this created a certain amount of unpleasant excitement.

Despite its shallow draught even a Harbour Defence Motor Launch (HDML) could be at risk when minesweeping. In April 1946 HDML 1328 was about to commence its first lap at Rabaul when a Japanese moored mine bumped along the starboard side before it was swept and then detonated by a Boys anti-tank rifle. Able Seaman Blair Mason states: ‘I can recall, even today, the sickening feeling of hopeless fear during those few seconds.’

On 18 November 1941 the auxiliary minesweeper HMAS Uki sighted a German GY* mine drifting near Montague Island. Norm Denovan (ex-Uki) recalled ‘Correct procedure would have been to destroy it, but much to our dismay the Skipper decided to recover it, and take it with us to Melbourne to let the experts see what made it tick.’ Volunteers were called to take the whaler over and bring the mine back. There was a ready response, Norm Denovan among them.

There was a bit of a sea running…and when we got to within about 25 ft [8 m] of the mine, the First Lieutenant who was hanging over the side, looking for a ringbolt to attach the towline to, fell overboard. The whaler drifted away and he swam to the mine, then supported himself by hanging on to one of the horns. He couldn’t find a ringbolt, so he made a running bowline and placed it over one horn. Then we towed it back to Uki, and after a few anxious moments, we lifted it out of the water and over the stern on the kite davit. We lashed it to the deck over the ERA’s mess, but they didn’t seem too happy about it.

Uki put into Eden and advised DNO Melbourne of her plan to deliver their mine to him. This produced a predictable response, and the mine was destroyed off Gabo Island.

When the mooring of a GY* mine parted the mooring spindle was withdrawn by a spring and the arming switch was either opened or the mine detonated. However barnacle growth could prevent movement of the mooring spindle, and barnacles are to be seen on the mine. This mine could have been detonated by either:

a horn being broken when used as a towing point or hitting the ship’s side during recovery, or

the mooring spindle moving inwards if the base of the mine landed heavily on the deck.

Damage to AMSs in China from Allied ground mines

The Royal Navy and United States Navy used wooden-hulled minesweepers for sweeping Allied ground mines. They were fitted with a comprehensive degaussing (DG) coil system which enabled them to operate safely against magnetic mines in depths as shallow as 6 m. The AMS was steel-hulled and only had a rudimentary DG coil system. The minimum safe depth against magnetic mines in the southern magnetic hemisphere was 30 m. When AMSs were deployed to China in 1945 the nearest degaussing range was at Manus Island in the opposite magnetic hemisphere, and the steel-hulled AMSs were forced to operate in China with their degaussing switched off. Aerial ground mines were laid in depths of up to 46 m and they all posed a threat to AMSs in China. The 223 magnetic mines laid by RAAF Catalinas at China in 1945 were fitted with sterilizers to automatically disarm the mines after a preset period. It was expected that only 1 percent of the mines would still be armed, and this represented an acceptable risk. The RAN was apparently unaware of the 195 mines laid by the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) at Hong Kong prior to November 1944, and these mines would not have been fitted with sterilizers.

On 26 September 1945 HMAS Strahan was on an anti-piracy patrol at Hong Kong and was damaged by a magnetic mine. The mine exploded in 22 m under the wardroom flat (aft) and slightly to port. There were four casualties, but none were serious. With her main engines and steering gear out of action she was towed back to harbour by HMAS Wagga and the RN Fleet Tug Integrity. Strahan only suffered minor damage that could be repaired locally.

On 6 November 1945 HMAS Ballarat was leading the 21st Minesweeping Flotilla (MSF 21) back into harbour at Amoy in 16 m when a RAAF 450 kg magnetic mine detonated about 6 to 9 m astern. There were no casualties, and HMAS Bendigo towed Ballarat back into harbour. Hull damage was only superficial, and testimony to the rugged design and the quality of workmanship for the AMS. The steering engine and shaft had been displaced, and the cover plate for the port plummer block had been cracked. This damage was rectified by onboard repairs. A total of 17 rivets were replaced and only four rivets had sheared. Commander Read, Commanding Officer Ballarat and Senior Officer MSF 21(SO 21), signalled ‘apparently one of the 1 percent not yet sterile’.

HMA Ships Swan and Warrnambool, Great Barrier Reef 13 September 1947

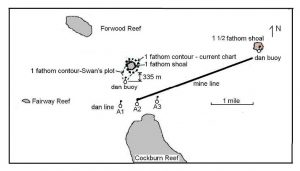

HMAS Bungaree laid 5226 Australian-made Mk XIV mines in 38 minefields along the Great Barrier Reef from Townsville up to Cockburn Reef near Cape Grenville. There were 116 mines for Minefield HOME at Cockburn reef and the mine line is shown in Figure 3. They were laid on a bearing of 250 degrees with a spacing of 48 m and the tops of the mines 2.3 m below MLWS. Many coral outcrops prevented Bungareelaying the western end of the mine line closer to Cockburn Reef.

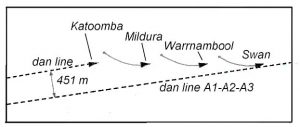

Operation KILHOME was the clearance of this minefield, and 34 mines had parted their mooring prior to the commencement of minesweeping on 13 September 1947. Clearance was by the 1st Division of the 20th Minesweeping Flotilla – HMA Ships Swan (Senior Ship, with A/Captain R.V. Wheatley RAN as CO and SO 20), Warrnambool (Leader, with A/Commander A.J. Travis RAN as CO), Mildura and Katoomba, with HDML 1329 (precursor operations and mine destruction) and HDML1326(mine destruction). Motor Stores Lighter MSL706 was stores support vessel. Swan had a draught of 3.4 m and was at risk, however a HDML had a draught of only 1.6 m and was suitable for precursor operations. It was normal procedure for sweeping to be across the mine line and commence outside the mine line, but neither was possible. Minesweeper tracks were only inclined to the mine line by 10 degrees, and pinnacles prevented the initial dan line being south of the mine line by a suitable distance. The minesweeping plan was:

HDML1329 conduct a visual reconnaissance for the mine line.

HDML1329 lay dan buoys, including the initial three dan buoys for the channel – dan buoys A1, A2 and A3.

HDML1329 ‘open up’ the mine line by sweeping a safe path for Swan next to dan line A1-A2-A3.

Clearance sweeping in G Formation port for the first lap, with Swan as guide and running along dan line A1-A2-A3 and Katoomba laying four dan buoys for the second lap.

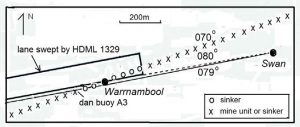

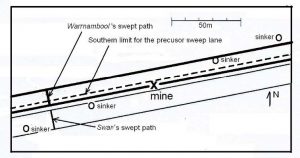

HDML1329 completed a clear run from the west with port Oropesa at 8.2 m (4½ fathoms). The sweep passed over four mine sinkers and the fatal mine was only just outside the swept path, Figures 5 and 6 refer. (Actual plots are not available, and these figures are estimated plots based on vector analysis of evidence presented at the two Boards of Inquiry into the sinking of Warrnambool. When Operation KILHOME was completed in October 1947 mines were swept by a HDML south of the fatal mine location).

The sweeps were at 9.1 m (5 fathoms) for clearance sweeping. A change in current had moved dan line A1-A2-A3 an estimated 19 m south after precursor sweeping, and the dan line was now south of the fatal mine. After all three sweeps parted due to fouling the bottom between dan buoys A1 and A2 the other three minesweepers followed in Swan’s wake.Swan ran on the A2-A3 transit after passing dan buoy A3. After Warrnambool passed dan buoy A3 the Officer of the Watch was ordered to disregard the A2-A3 transit and keep Swan on a bearing of 080 and not more than 081. At 1556 Swan was hoisting a signal to run starboard sweeps to a depth of 5.5 m (3 fathoms) for a run to the west when Warrnambool hit a mine. Captain Wheatley observed that ‘She appeared to be lifted out of the water a bit, settled down and then slewed to starboard and her mast fell down on her starboard side’. At 1745 Warrnambool rolled over and sank.

Four sailors were killed. (They are excluded from the Roll of Honour at the Australian War Memorial (AWM), Canberra since the AWM cut-off date for inclusion is 30 June 1947). Three officers (including the CO) and 26 sailors were injured, and there were 28 cases of severe shock. At 1748 Swan proceeded to Cairns with despatch with the survivors. Injured survivors were admitted to Cairns General Hospital on 15 September, and some in a less serious condition were flown to Balmoral Naval Hospital the same day. Others were transferred by RAAF Aerial Ambulance to Greenslopes Repatriation Hospital in Brisbane the next day. The original Board of Inquiry pointed out that only by good fortune did Swan escape the fate of Warrnambool. The mine spacing across Swan’s track was only 7.5 m and she had a swept width of 14 m (11 m beam plus 1m mine diameter plus a 2 m allowance for a mine moving towards the hull due to water flow around the hull). Irrespective of where Swan crossed the mine line she had to encounter at least two mine locations, and either pass safely over sinkers or hit a mine. Lady Luck smiled on Swan – she passed over two sinkers before the fatal mine passed very close to her port side.

Bibliography

Advanced HQ RAAF to Air Board, Melbourne, 2 October 1945, enclosure, RAAF Command Report on RAAF minelaying operations, National Archives of Australia (NAA): A1196, 60/501/155.

AWM to HMAS WarrnamboolAssociation, 4 March 1997.

BR 1736 (50) (5), The Blockade of Japan,published as CB 3303 (5) in 1957, Admiralty.

Cashford, N., All Theirs! ALD Design & Print, Sheffield, 2004.

Casualties, [US] Navy and Coast Guard Ships<www.history.navy.mil/faqs/faqs82-1.htm> (30 April 2005).

Form S. 309 minelaying record for Operation HOME, NAA: MP 1185/8, 1924/4/733.

Gill, G.H., Royal Australian Navy 1942 – 1945, Australian War Memorial (AWM), Canberra, 1985.

Gill, J.C.H., ‘Lost by enemy action’, As You Were, 1947, AWM, Canberra, 1947.

Gillett, R., Australian & New Zealand Warships 1914- 1945, Doubleday Australia, Sydney, 1983.

Grovenor, J., and LM Bates, Open the Ports, William Kimber, London, 1956.

HMAS BendigoROPSeptember 1945, NAA: AWM78, 62/1.

HMASBungaree to ACNB, 25 November 1943, NAA: MP1185/8, 1924/4/733.

HMASKalgoorlieROP, September 1944, NAA: AWM78, 185/1.

HMASStrahanto SO 22, 1 Oct 1945, NAA: AWM78, 325/1.

HMAS Warrnambool casualties, NAA: AWM124, 4/452.

Journal for the use of Midshipmen, S.519, prepared by Mr JD Stevens RAN (later Rear Admiral).

Letter from Blair Mason 21 May 2005.

Letter from Lieutenant Commander Bert Dechaineux RAN (ret) 21 April 2004.

Letter from Martin Howley (ex-Warrego) 11 July 2004.

Lott, A.S., Most Dangerous Sea,Bracken Books, New York, 1959.

Macklin, R., One False Move, Hachette Australia, Sydney, 2012.

Minute by DGA/DE (A) 29 September 1942, NAA: MP1049/5, 1924/4/685.

Minutes of Board of Inquiry 14 July 1941, NAA: D305, 76/20.

National Standards Laboratory (NSL), Sydney to ACNB, 11 November 1944, NAA: MP1049/5, 2026/25/193.

Nesdale, Iris, Small Ships at War: they Joined the RAN,published by the author,1993.

Odgers, G., Air War against Japan 1943 – 1945,AWM, Canberra, 1957.

Original Board of Inquiry into the loss of HMAS Warrnambool, Minutes of evidence, NAA: MP 981/1, 603/280/2110.

Pennock, R., ‘Were they the first?’,Wartime, Issue 20, AWM, Canberra.

Second Board of Inquiry into the loss of HMAS Warrnambool held on board HMAS Australia at Sydney on 30 December 1947, Minutes of evidence, NAA: MP 981/1, 603/280/2110.

SO 20 to ACNB, 14 September 1947, NAA: MP981/1, 603/280/2110

SO 20 ROP 16 October 1947, NAA: AWM 78, 377/3.

SO 21 to Captain Escort Forces, British Pacific Fleet, 17 November 1945, NAA: AWM78, 378/1.

Southall, I., Softly Tread the Brave,Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1960.

Turner, J.F., Service Most Silent, George G. Harrap and Co Ltd, London, 1955.

Waye, G., Minesweeping Operations by Australian Minesweepers from 3–9–39 to 31–8–46,Sea Power Centre-Australia file.