- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - WW1, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Westralia I, HMAS Melbourne II, HMAS Diamantina I

- Publication

- March 2013 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Walter Burroughs

In the December 2012 edition of this magazine there appeared an article on the Cocos and Christmas Islands. This theme is continued with a discussion on Nauru which has many historical similarities to Christmas Island and both feature in the Australian Government’s ‘Pacific Solution’ to illegal immigration.

The Pleasant Isle

Nauru is a small oval shaped island of just 8.1 sq miles or 21.1 km2, measuring 6 km by 4 km with a circumference of 19 km, lying in the western Pacific just south of the equator. It has a small fertile fringe and a central plateau rising to 65 metres above sea level. Its nearest neighbour 305 km to the east is Baanaba (Ocean) Island in Kiribati, formerly the Gilbert and Ellice Islands. The current population is 9,378 (2011 estimate) which had been larger, but from 2004 to 2006 some 1,500 immigrant workers were repatriated. It is also one of the world’s smallest independent nations. Nauru is remote, being 2,174 nautical miles or 4,029 km and about 5 hours flying time from Sydney and from Honolulu.

The island is surrounded by a coral reef which is exposed at low tide. There is no natural port but a deep water anchorage is served by a cantilever system for loading phosphate and by lighters for the loading and discharge of other cargo.

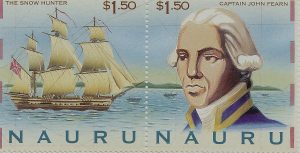

Nauru was populated by a Micronesian race at least 3,000 years ago but was unknown to Europeans until discovered in 1798 by Captain John Fearn in the whaling ship Snow Hunter on a voyage from New Zealand to China. Fearn, an ex-Royal Naval officer, named it Pleasant Island due to the attractive and lush vegetation and friendly nature of its inhabitants. Subsequently whaling ships called for supplies, especially fresh water. In return they brought disease, and traded alcohol and firearms leading to tribal warfare. The Sydney Morning Herald of 16 August 1843 published an extract from the diary of Captain Beckford Simpson of the barque Giraffe which had called at Pleasant Island in February of that year when on passage from Sydney to Manila, which relates: ‘…this island and many others in the Pacific are infested by Europeans, who are either runaway convicts, expirees, or deserters from whalers, and are for the most part men of the very worst description, who it appears prefer living a precarious life of indolence and ease with the unenlightened savage.’

Anglo-German Convention

During the late 19th century rivalry between colonial powers caused friction in the Pacific which in 1886 led to the Berlin Anglo-German Convention, whereby the oceanic area was divided into two spheres of influence. The small Pleasant Island fell within an agreed German sphere. Two years later on 01 October 1888 the German gunboat SMS Eber arrived and landed an armed party of 36 marines who hoisted the German flag and installed a new governor. The marines held the native chiefs hostage until the warring islanders had been disarmed, alcohol banned and evangelism encouraged. The new authorities were greatly assisted by William Harris, an escaped prisoner from Norfolk Island, who had settled on the island and married a local woman and with her had several children. In the same year the island, then known as Nawodo, was incorporated into the German Marshall Islands Protectorate.

Discovery of Phosphate

In 1899 an enterprising Englishman, A.F. Ellis of Sydney, discovered that a lump of rock which originated from Nauru and was being used as a door-stop in his firm’s office was phosphate rock of the highest quality. The phosphate rock is amongst the highest grade in the world with a typical percentage of 80% phosphate to lime. This led to the formation of the Pacific Phosphate Company (PPC), a British company which purchased the rights to mine the minerals on Nauru and Ocean Island. Exports of ore began from 1907 with the assistance of indentured labour imported from China and neighbouring islands. Nauru then developed as one of three great phosphate islands in the Pacific, the others being Baanaba (Ocean Island) in Kiribati and Makatea in French Polynesia.

Impacts of WW I

At the outbreak of WW I Nauru had a native population of 1,400 plus some 100 Europeans who were predominately English and German. Locally, the administration was conferred on the manager of the Jaluit Trading Company, but it practical terms it was run by the PPC.

Nauru and Yap, which are 2,000 miles apart, were the main communications stations covering the German Pacific chain. The Bitapaka station at Rabaul was still unfinished at the outbreak of war and was then hurriedly completed.

After assisting in the successful occupation of German Samoa on 9 September 1914 the cruiser HMAS Melbourne landed a surprise armed party of 4 officers and 21 men on the island and, on capture of the administrator, gained an unconditional surrender without a shot being fired. The landing party then disabled the radio station. As Nauru was short of provisions, Melbourne did not leave an occupation force behind and it was not until 6 November 1914 that an official occupation took place and the British flag was raised over the island.

League of Nations Mandate

Under a section of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles sovereignty of Nauru was vested in the British Crown. Later a Nauru Agreement was entered into by Australia, Britain and New Zealand which led to the creation of the British Phosphate Commission (BPC), which took over mining. The BPC was a board with representatives from Australia, Britain and New Zealand who managed the extraction of phosphate from Christmas Island, Nauru and Ocean Island from the 1920s until the 1960s. In 1923 Australia was granted a League of Nations mandate over the island.

Impacts of WW II

On 6 and 7 December 1940 the German auxiliary cruisers HSK Komet and Orion accompanied by their supply ship Kulmerland sank five ships waiting to load phosphate in the vicinity of Nauru, after which Komet shelled the mining areas, oil storage depots and the shipping facilities. These attacks seriously disrupted phosphate supplies which were needed in Australia and New Zealand for fertiliser but more importantly for the manufacture of explosives. In response, two detachments of about 50 men with two 18-pdr guns drawn from the 2/13 Australian Army Field Regiment were sent in February 1941 to garrison Nauru and Baanaba against a possible repeat of raider attacks. These were known as Heron Force (Baanaba) and Wren Force (Nauru). Two new detachments were raised in Sydney, known as the Ocean Island Force and the Nauru Force, and these relieved Heron and Wren Forces in August 1941. They voyaged to the islands in HMAS Westralia which on her return escorted a group of merchantmen which had taken off a total of 93 non-essential Europeans from the islands.

The day after Pearl Harbor in December 1941 Japanese planes carried out a series of bombing raids which silenced the radio station, after which the decision was taken to evacuate the remaining Europeans and the Australian garrison. In February 1942 some 500 persons including the garrison were evacuated using the Free French destroyer Triomphant which was supported the BPC ship Trienza. Seven Europeans remained at Nauru including the Administrator Lt. Colonel F.R. Chalmers, CMG, DSO, and six Europeans remained at Ocean Island. Owing to atrocities of war only one of them survived captivity.

The first failed attempt to occupy Nauru and Ocean Island was made when a Japanese naval invasion force of one cruiser, two destroyers and two minelayers with troops under command of Rear Admiral Shima Kiyohide departed from Rabaul on 11 May 1942. This force was attacked by the US submarine S‑42, leading to the loss of the large minelayer and flagship IJNS Okinoshima. Attempts were then called off when reconnaissance planes sighted US carriers.

A second Japanese invasion force led by the cruiser IJNS Ariake departed Truk on 26 August 1942 and three days later, following a bombardment by Ariake, a landing party of the 43rd Guard Force conducted an unopposed landing. They were joined by the 5th Special Base Force Company intent on building an airstrip. By October 1942 there were 11 officers and 249 Japanese soldiers on Nauru. With imported labour for construction work by June 1943 the population reached 5,187, which included 1,388 military personnel. In September 1943 the Japanese began sending islanders to work as labourers in the Truk (now Chuuk) and Caroline Islands but this was interrupted when a ship intended to take evacuees was torpedoed and sunk. The same month a Japanese freighter bringing supplies and personnel was torpedoed and sunk with the loss of over 400 lives. Of the 1,200 Islanders deported as labour many suffered severe hardship and only 737 survivors returned after the war.

The airstrip led to multiple bombing attacks by the US Army Air Force from March 1943, but the island was bypassed in the Allied drive north. The current excellent international airport enjoyed by Nauru is a legacy of this earlier wartime construction. On 8 September 1945 Australian aircraft dropped leaflets on the island signalling that the war was over and that an occupation force would soon arrive. Five days later on 13 September HMAS Diamantina escorting the Australian merchantmen Burdekin River and Glenelg River arrived when the Japanese commandant Hisayaki Soeda surrendered to Brigadier J.R. Stevenson on board Diamantina. The following day 500 troops from the 31/51 Battalion AIF landed and raised the union flag. At the time of the surrender there were 2,681 Japanese troops and 1,054 Japanese and Korean workers on the island, out of a total population of 5,329. Owing to Allied bombing and air superiority, the islands had not received any supplies for over a year. The inhabitants were in desperate need of food and there was a general breakdown in health and sanitation. Some 300 of the former enemy had died and another 130 were hospitalised. A similar surrender ceremony was held on board Diamantina off Ocean Island on 1 October 1945 where an Australian force of 140 men took over control from a Japanese garrison of over 513 men, mostly naval personnel. After the two merchant ships had discharged all their supplies they embarked the Japanese prisoners and Koreans who were repatriated firstly to Bougainville. All but one platoon was withdrawn in December 1945 and it was finally withdrawn in February 1946.

United Nations Trusteeship and Independence

In 1947 a United Nations Trusteeship was established over the island, with Australia, Britain and New Zealand becoming trustees for 20 years, when self-determination was to be enacted. Nauru became self-governing in January 1966 and became fully independent on 31 January 1968. In 1967 the people of Nauru purchased the lucrative assets of the BPC for $A21M and in June 1970 control passed to the locally owned Nauru Phosphate Corporation. Income from the mines gave Nauruans one of the highest standards of living in the Pacific with the economy peaking in the early 1980s. The small republic had at one time annual revenues in excess of $A100M providing a surplus of about $A80M, which was invested in a development fund, mainly in international real estate. At its peak this fund was valued at over one billion dollars. Inexperience, economic mismanagement and extravagant spending by Nauru led to financial ruin and a dramatic decline in living standards. Phosphate reserves are now almost entirely depleted, which has left a barren terrain. Run-off has also affected the surrounding seabed.

In 1962, well before Nauru took over the phosphate industry and achieved independence, the United Nations had offered a cautious note:

‘The problem of Nauru presents a paradox. The striking contrast is between a superficially happy state of affairs and an uncertain and indeed alarming future… But this picture of peace and well-being and security is deceptive. Indeed it is a false paradise. For these gentle people are dominated by the knowledge that the present happy state of affairs cannot continue.’

Somewhat illogically, this tiny speck in the South Pacific with finite resources and no long term future was granted full independence as a stand-alone nation with little thought for future social and structural development. A legacy of phosphate mining and subsequent abundance of money resulted in a heavy reliance on imported goods. Unfortunately, this trend has continued with a highly urbanised community hardly able to sustain itself. With the collapse of the mining industry the population has begun to decline, but historically it remains far in excess of sustainability given the existing resources. It is noteworthy that the neighbouring but smaller Ocean Island of 6 km2 (now Baanaba) also reliant on phosphate mining, had similar problems to Nauru; but after WW II the British authorities relocated most of the population to Fiji, thereby avoiding latent problems. The current population of Baanaba is about 330 persons. A plan by partner governments to resettle Nauruans on Curtis Island off the north coast of Queensland was abandoned in 1964 when the islanders decided to stay put.

Over a century of continuous mining had stripped the island of four-fifths of its topsoil creating a virtual desert. In 1989 Nauru took legal action against Australia in the International Court of Justice over Australia’s administration of the island and, in particular, its failure to remedy the environmental damage caused by mining. This led to an out-of-court settlement to rehabilitate mined-out areas. Plans to rehabilitate the islands were drawn up in 1993 with compensation paid by Australia and with Britain and New Zealand paying a small annual subsidy. In the 1990s Nauru briefly became a tax haven and money laundering centre but this has now ceased.

Under an informal agreement Australia is responsible for Nauru’s defence and the country uses Australian currency. In September 2005 a Memorandum of Understanding between Australia and Nauru provides the latter with financial aid, currently running at about $A20M pa, and technical assistance. In return Nauru provides assistance with the housing of asylum seekers while their applications to enter Australia are processed. In addition to aid another $A8M is generated annually from the camps in accommodating, feeding and transporting overseas employees and officials. Playing a diplomatic role in supporting foreign government initiatives through the United Nations, the Nauruan Government has also managed to gain aid from a number of other countries, notably Taiwan (ROC) and China (PRC) and Russia.

The Pacific Solution

Over recent times problems have arisen through the arrival in Australia of a large number of persons claiming refugee status. While most in this category arrive by air a large number have arrived by sea, usually after an intermediate stop in Indonesia. During the period 1 July 1998 to 27 July 2012 there were 33,412 arrivals by boat, most of who claim refugee status and apply for protection visas. Just as the Allied forces in 1943 bypassed Nauru and left the Japanese garrison to wither on the vine, again with the arrival of the 21st century Nauru had been largely bypassed and left to wither. Help came from a most unexpected quarter when in August 2001 a Norwegian container ship, responding to a distress call, rescued 438 Afghans from a small fishing boat sinking in international waters about 140 km north of Christmas Island. In what became known as the ‘Tampa Affair’ the ship, despite Australian protestations, anchored off Christmas Island and eventually its human cargo was transferred to HMAS Manoora. In the same timeframe 231 Iraqi and Palestinians were picked up from a boat off the Ashmore Reef and these were added to Manoora’s passengers, all of whom were taken to Nauru.

In response to the ‘Tampa Affair’ the Australian Government developed its ‘Pacific Solution’ of transporting asylum seekers to detention centres on small remote Pacific islands, rather than allowing them to land on the Australian mainland while their refugee status is determined. The Pacific Solution comprises three elements. Firstly, for this purpose many smaller islands were excised from Australia’s migration zone or Australian territory. Secondly, the Australian Defence Force commenced ‘Operation Relex’ to interdict vessels carrying asylum seekers. Finally, these asylum seekers were removed to third countries in order to determine their refugee status and moved using RAN ships to detention centres established at Christmas Island, Manus Island and Nauru.

From the time of the first arrivals at Nauru in 2001 until the centre on the island was closed in March 2008, a total of 1,321 (which includes 19 births and one death) have been processed at Nauru. While there are arguments for and against this policy it could be seen as being partially successful as it stemmed the refugee flow. The cost however appears disproportionately high with over one billion dollars spent on the overall scheme. On Christmas Island new detention facilities were built and on Manus these were formed from PNG Defence Force naval base, previously HMAS Tarangau, and at Nauru two new camps were built. Christmas Island can house about 1,500 detainees (note at one time the maximum number actually held was about 2,700), Manus 900 and Nauru 1,500. All centres are manned by civilian contractors. In 2008 the Government closed the off-shore centres at Manus and Nauru. Since then, with increasing numbers of refugees arriving by boat, these centres were refurbished and are now being reopened with the first arrivals of refugees coming from Christmas Island to Nauru by air charter in September 2012 and at Manus Island in November 2012.

Lessons from History

The assimilation of new arrivals into the Australian community has, since the infancy of a colonial past, provided a constant stream of difficulties from intransigent British and Irish convicts to indentured Pacific Island labour, Chinese gold workers and post war European migrants. Further difficulties arising from the new chapter of migrants seeking escape from war torn regions of the Middle East should come as no surprise. In Australia problems now arise from the acknowledgement of obligations under the United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees which can run counter to certain national community expectations. The Pacific Solution seeks to provide a short-term interim solution which satisfies few.

This remote Pacific atoll, first known as the Pleasant Island, has a long history which largely remained undisturbed for three millennia. But since European discovery just over two centuries ago the changes have been traumatic. Nauru has moved from a traditional tribal society to a colonial outpost, and then, surprisingly, been involved in two world wars and finally been granted a hasty and seemingly unsustainable independence. In 2003 the respected Economist called Nauru ‘…one of the world’s most dysfunctional countries…’, a statement unfortunately supported by the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade which in 2004 stated that Nauru is among the most egregious examples of corruption, profligacy and mismanagement in the South Pacific. While progress has been made it remains a troubled nation dependent upon aid. A new chapter in the islands history has just begun and Australia and in particular its Defence Forces may yet have much more involvement in making this once more a Pleasant Island.

Bibliography

Brown, M. Anne (Ed), Security and Development in the Pacific Islands, Lynne Rienner, London, 2007.

Gill, G. Hermon, Australia in the War of 1939-1945 Royal Australian Navy 1939-1942, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1957.

Gill,G.Hermon, Australia in the War of 1939-1945 Royal Australian Navy 1942-1945, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1968.

International Business Publications, Nauru Country Study Guide, Washington, 2008.

Jose, A. W., Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918, Vol. IX, The Royal Australian Navy (Eighth Edition), Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1940.

Mansted, Rachel, The Pacific Solution- Assessing Australia’s Compliance with International Law, Journal – Bond University Student Law Review Vol 3 Issue 1, Gold Coast Qld, January 2007.

McCarthy, Dudley, Australia in the War of 1939-1945 South-West Pacific Area First Year, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1959.

Metcalfe, Susan, The Pacific Solution, Australian Scholarly Publishing, Melbourne, 2010.

Numan, Peter, HMAS Diamantina – Australia’s last River Class frigate 1945-1980, Slouch Hat Publications, Rosebud, Victoria, 2005.