- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - WW1

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2022 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Walter Burroughs

Since 1788 Norfolk Island has been occupied and governed from the Australian mainland. As the following story unfolds, however, we shall see that for six years during WWII it was occupied and controlled by armed forces from New Zealand.

Early History

Norfolk Island lies about 1400 km from the eastern seaboard of New South Wales and 1100 km from the west coast of New Zealand. It is a semi-tropical island approximately 5 x 8 km, of only 3500 ha. Captain James Cook in HMS Resolution landed here on 10 October 1774. It was then uninhabited, but archaeological investigations have since revealed an earlier Polynesian settlement. The scenery reminded Cook of New Zealand and he was pleased with the mild climate, fertile soil, plentiful fresh water, and an abundance of tall pines and native flax, which he believed could supply masts and sails. Cook’s journal notes: ‘I took possession of this isle…and named it Norfolk Isle in honour of that noble family’.

Cook’s description of the island was so encouraging that instructions given to Captain Arthur Philip with his First Fleet to colonise New South Wales had an additional clause inserted which in part reads: ‘Norfolk Island…being represented as a spot which may, hereafter, become useful, you are, as soon as circumstances will admit of it, to send a small establishment thither to secure the same for us, and prevent it being occupied by the subjects of any other European Power.’1

Soon after the 1788 arrival of the First Fleet Captain Philip despatched Lieutenant Philip Gidley King in charge of a party of 15 convicts (nine males and six females) and seven free men to establish a settlement on Norfolk Island for growing additional food. The Port Jackson settlement was running short of supplies, with food production proving difficult in the demanding soil and climatic conditions.

On 19 March 1790 the colony was left in dire circumstances when the flagship HMS Sirius misjudged the wind and was driven on to a reef off Norfolk Island. Luckily there was no loss of life and most of her stores were salvaged but the damage to her hull was irreparable.

The island remained a penal settlement until 1855, except for 11 years between 1814 and 1825 when it was abandoned because of unfavourable economic conditions. As the descendants of Bounty mutineers had outgrown their remote Pitcairn Island home, in 1856 they accepted relocation to the larger and better-established Norfolk Island. Through them a seasonal whaling industry was established using American designed open boats.

A leading member of the Pitcairn islanders was George Hann Nobbs. Born in 1799, he entered the Royal Navy as a midshipman and became a lieutenant in the Chilean Navy under the swashbuckling Lord Cochrane. In 1828 Nobbs came to Pitcairn Island where the dying John Adams, the last survivor of the Bounty mutineers, invited George Nobbs to succeed him in the roles of pastor and teacher. Nobbs, who was later ordained as an Anglican minister, became a devoted leader who cared for his people for over half a century before dying on Norfolk Island in 1884 at 84.

The role of the church was further enhanced when an important Melanesian Mission was established on Norfolk Island in 1867. Known as St Barnabas College, a magnificent church was built and served as a training centre for missionaries throughout the South Pacific, which continues to this day.

In 1914 the British Government handed over responsibility for the island administration, with it becoming an external territory of Australia. An illuminating description of the island and its people is provided by its former Chaplain Benjamin Brazier who left the island in late 1918, saying: ‘The climate is remarkably genial and before the war attracted a great number of visitors. It was fast becoming known as a health resort, and was spoken of as the Madeira of the Pacific’.2 The reverend gentleman goes on to acknowledge a lack of amenities with only one bicycle on the island, and the cable station suppling the only news of the outside world by posting up a bulletin. Brazier also expressed concern that the small population mainly brought from Pitcairn Island could lead to inbreeding.

While it is a small and remote island its people are patriotic. Nine men departed for the Boer War, and 81 (including two females) enlisted for military service in WWI, of whom 13 died on active service. These wars were far away, but not so WWII, when war came to Norfolk Island.

Organisation and Command in the Pacific Theatre

The initial responsibility for the defence of Allied interests in the Far East and the Pacific was poorly coordinated by ABDACOM (American-British-Dutch-Australian Command) which was established in December 1941. After the fall of Singapore and Japanese advances in the Dutch East Indies, it was quickly disbanded by the end of February 1942. An in-principle agreement was then reached between Prime Minister Churchill and President Roosevelt, with planning for strategic defence of the Pacific region becoming an American responsibility, and the Indian Ocean a British responsibility. This resulted in directives approved on 30 March 1942 for the establishment of two broad commands for the South-West Pacific under General MacArthur and the Pacific Ocean Area under Admiral Nimitz. The dividing line between these two commands meant that Australia and New Zealand were in two different camps and Norfolk Island was with New Zealand.

In his wartime history of Norfolk Island local historian Gil Hitch3 says: ‘Norfolk Island’s war history is not part of Australia’s war history’. There is logic to this statement as in the Official History of Australia in the war of 1939-45, Norfolk Island is no more than a footnote, deferring to the New Zealand Official War History.

In strategic terms, Norfolk Island is the only land on the air route between Australia, New Zealand and New Caledonia. It also has another importance as in 1907 a receiving station had been established at Anson Bay, forming part of the transpacific submarine cable link between Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, Canada and Britain. Concerns were held for the security of this service as it had been cut by the German cruiser SMS Nurnberg at Fanning Island in 1914.

In 1938-39 the Department of Civil Aviation conducted aerial surveys of potential sites for RAAF aerodromes which included Norfolk Island. At this time in official correspondence Australian officials advised their New Zealand counterparts that the defence of Norfolk Island was primarily a naval responsibility and that any aerodrome constructed on it would be more of a liability than an asset.

The Administrator, Major-General Sir Charles Rosenthal, recruited a local volunteer militia, and on 4 September 1939 this unit of about 50 men was formally established as the Norfolk Island Infantry Detachment (NIID). The NIID was dedicated to guarding key facilities including the strategic cable station. A further detachment of military troops from 1st Australian Infantry Battalion, City of Sydney’s Own Regiment, was despatched to Norfolk. These reinforcements under Major Farlow arrived in April and July 1942 using the Burns Philp ship SS Morinda on her regular six weekly run from Sydney to Lord Howe, Norfolk and the New Hebrides.

The Americans under Vice Admiral Robert Ghormley, then headquartered in Noumea, had further thoughts about Norfolk Island and its unique position, equidistant between Australia, New Zealand and New Caledonia. They saw advantages in its being viewed much as ‘a stationary aircraft carrier’. With a site for an airstrip readily available, it could become a base for anti-submarine patrols, and a staging post for land-based aircraft moving to the battlefronts in the Solomons and further north. This was strongly supported by Air Commodore Robert Goddard, New Zealand Chief of Air Staff (later Air Marshall Sir Robert Goddard).

American invasion of the Great South Land

American troops first came to Australia during WWII in the ‘Pensacola Convoy’ which had been destined for the Philippines but was diverted and arrived in Brisbane on 22 December 1941. A huge influx of 8398 troops boarded the Queen Mary4 in Boston and thence, via Key West, Rio de Janeiro and Cape Town, arrived in Sydney on 28 March 1942. The troops, under Brigadier-General Robert H. Van Holkenburg, were mainly from the 40th Artillery Brigade comprising artillery and anti-aircraft gunners, together with the Army Air Corps and other support groups.

Another large contingent comprising the 41st Division came in three convoys over a few months. Early arrivals were the 162nd Infantry Battalion5 of the Oregon National Guard who, after a voyage from New York via Panama, arrived in Melbourne on 9 April. Another echelon, including the Divisional Headquarters, came in a convoy which included RMS Queen Elizabeth from San Francisco, arriving on 6 April. As Melbourne could not accommodate the ‘Queens’ they disembarked in Sydney and troops proceeded to Melbourne by train or were transhipped in smaller Dutch steamers. The remaining elements of the Division arrived on 13 May.

Americans in New Zealand

Unannounced on a cold grey day on 12 June 1942, Convoy PW 2076 arrived in Auckland, an event that would dramatically change the New Zealand way of life. In the van was the heavy cruiser USS San Francisco escorting five transports with ‘Doughboys’ and equipment from the American 37th Infantry Division. The transports comprised the ships President Monroe, Uruguay, James Parker, Tasker H. Bliss and Santa Clara, and completing the escort was the destroyer USS Farragut.

Again unannounced, two days later on a quiet Sunday, the fast transport USS Wakefield, previously the luxury liner SS Manhattan, with nearly 5000 ‘Leathernecks’ from the 1st Marine Division, under the command of Major General Alexander Vandegrift, arrived in Wellington. Surprisingly, once clear of Panama Wakefield made the voyage unescorted. Later information confirms the dangers involved at this time with the Japanese submarine I-22 operating off New Zealand’s east coast.

In mid-October 1942, perceiving a lacklustre performance, Admiral Nimitz ordered a snap inspection of Vice Admiral Ghormley’s command and in a matter of days he was relieved by the dynamic Vice Admiral William (Bull) Halsey. Halsey was seen as a foil to the domineering style of General MacArthur in an inter-service turf war of influence, priorities and resources in the Pacific War.

In February 1943 the US 3rd Marine Division arrived in Auckland, followed by the Army’s 25th Division. At the same time elements of the 2nd Marine Division that had fought in the Solomons arrived. At any one time between June 1942 and the next two years between 15,000 and 45,000 Americans were stationed in New Zealand preparing for operations in the Pacific.

Secret mission to Norfolk Island

Shortly after arrival, US Army Captain Ronald Husk from the 162nd Battalion was ordered to present himself to General MacArthur, the newly minted Supreme Commander South-West Pacific. The General required a first-hand military assessment of Norfolk Island and Husk was chosen to assemble a team and lead a secret mission to the island and report back upon his return.

Captain Husk and a few ‘experts’ departed from Sydney to Norfolk in ‘a small naval vessel’.6 This was almost certainly SS Morinda which departed Sydney for Norfolk Island on 14 April 1942 with an AIF contingent. Upon arrival they were met by the Administrator and the commanding officer of the NIID. On 26 April they reboarded their ship and returned to Sydney.

Aerial surveys of the selected site for an airstrip were conducted by a RNZAF Hudson aircraft. Ronald Husk returned to Norfolk Island in April 1992 to mark the fiftieth anniversary of his earlier visit.

The Husk visit also features in the ‘Commemorative Events Program – Celebrating 75 years of Peace in the Pacific’ held at Norfolk Island in August 2020. This noted: ‘…soon after they arrived US Captain Ronald W. Husk and a small team spent four days on Norfolk Island making a military assessment. Their work was supplemented by the first aerial survey of the island by the RNZAF on 26 April 1942’.

Yankee Ingenuity and Aussie Grit

Following receipt of Husk’s report, plans were immediately put in place for construction of an airfield. An advance party of 14 technical staff under US Army Major H. Trimble arrived in MV Moamoa7 in late August 1942. They were followed on 31 August by over 200 volunteer workers from the Australian Commonwealth Main Roads and Public Works Departments, arriving in MV Yochow. This labour force was not exactly novices having previously been involved, from November 1941 to April 1942, in the construction of Tontouta Aerodrome in New Caledonia. Heavy equipment came directly from America in MV Roseville on 20 September. She carried two launches, two large steel barges, five Caterpillar D8 tractors equipped as bulldozers, five Allis Chalmers HD7 tractors, and one 10-ton crane, plus diesel vehicles and generators. Construction of the airfield required the sacrifice of a treasured mile-long avenue of 500 majestic Norfolk Island pines, planted by convicts in 1835 at Longridge, which was a heavy price for the locals to bear.

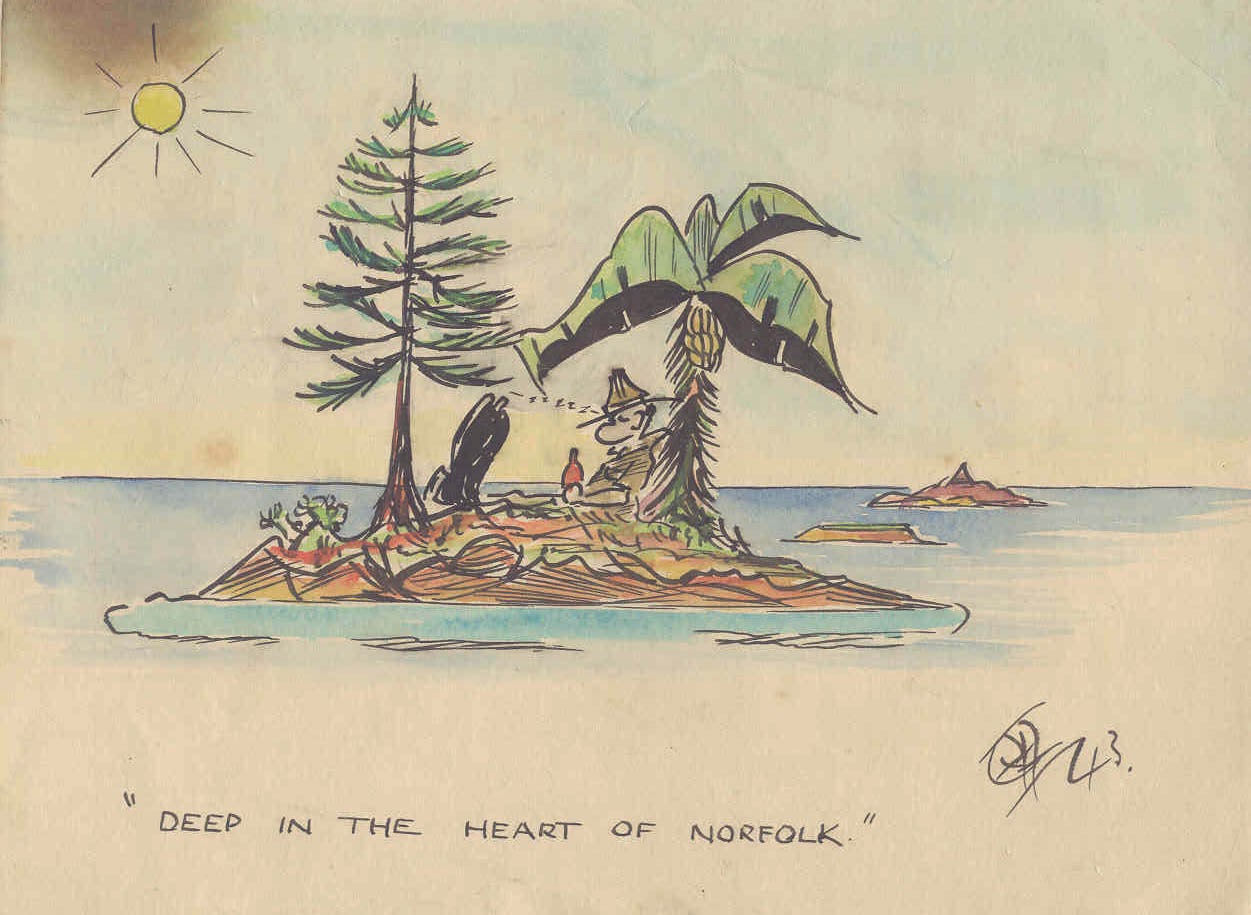

An unusual arrival in October was the yacht Golden Hind with a party of 12 Army and Air Force technicians. Their unit commander Staff Sergeant John Allan was an able cartoonist who lampooned the boredom faced by troops with endless training and sports fixtures making up for a lack of active service.

Another US Army Small Ship SS Hanyang delivered 800 tons of ‘Marsden’ wire matting for the runways in two voyages, the first arriving on 20 November and the second exactly a month later. On the first voyage she also brought another 43 men for the airfield construction team.

New Zealand Army

For defence Vice Admiral Ghormley requested that New Zealand provide a garrison force of one infantry battalion, three batteries of anti-aircraft artillery, a hospital and other services and, when the airfield was complete, one flight each of fighter and dive-bomber aircraft.

On 26 September an advance party from the 36th Battalion of the Third Infantry Division under Lieutenant Colonel John W. Barry landed on the island through rough seas. After conferring with the Administrator, camp sites were selected and the main body of the 1488-man force, later termed ‘N-Force’, arrived in two stages on 9 and 14 October using the troopship Wahine and the Armed Merchant Cruiser HMNZS Monowai, escorted by the destroyer USS Clark. Also in October, the corvette HMNZS Moa was based at Norfolk to protect freighters unloading there.

The Gunners were well represented initially by ‘A’ Troop Field Artillery with 4 x 25-pounders, and later 152nd Heavy Battery with 4 x 6-inch guns and the 218th Composite AA Battery with 4 x 3.7-inch guns and 8 x 40mm Bofors.

N-Force was about twice the size of the permanent island population which gave an impetus to local industry in supporting their visitor. They received regular but limited supplies from New Zealand by a dedicated supply ship Waipari.Some members of the locally enlisted Norfolk Island Volunteers were integrated with N Force but now that the island was well protected AIF troops, including the remaining volunteers, were withdrawn to Sydney on 1 December 1942 in SS Hanyang.

Royal New Zealand Air Force

On 2 December the main runway was completed, and with the installation of 5000 feet of wire matting, the first aircraft, a RNZAF Hudson, piloted by Flight Lieutenant Geoffrey Keller, landed on Christmas Day 1942. The airfield was operational on 28 December 1942 with the first of two Hudson bombers beginning an era of dawn and dusk patrols. The RNZAF established an important radar station on the island in May 1943, which could detect targets out to 70+ miles, and which remained in operation until the end of hostilities. The island became an important staging point between New Zealand and forward areas with about 200 planes a month staged through Norfolk during the Pacific campaign.

In January 1943 the RNZAF presence increased with 200 men under Wing Commander Graham Coull arriving by aircraft and in Monowai. Many types of aircraft called here including Lockheed Hudson bombers and their replacement Ventura, Curtiss Kittyhawk fighters, Grumman Avenger torpedo bombers, and Douglas Dakota transports. Aircraft undertook bombing patrols, transport and air/sea rescue missions mainly operating in the large number of Pacific islands where the RNZAF had bases.

The RNZAF lost 350 men killed during the Pacific campaign, more than its Army and Navy counterparts. The New Zealand Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) was also based on Norfolk with its numbers peaking at 94 young women, mainly involved in cipher, administration and medical duties. This would have been a welcome distraction to the large number of males with limited social lives.

On New Year’s Day 1943 SS Karitane arrived from New Zealand with 300 live sheep, as the island’s stock of fresh meat was sorely depleted feeding its many visitors. On 26 January, Morinda made a scheduled call, discharged her cargo, and then embarked the first of the airfield construction workers being returned to Sydney. A month later on 24 February, Hanyang back-loaded more construction workers and surplus equipment to Sydney.

After an absence of some months from January 1943 Japanese submarines were again active in the waters between New Caledonia and the east coast of Australia, when six Allied ships were sunk. On 16 January Monowai was attacked by I-20 but all torpedoes missed. During this period the island’s defence was tested. Coastwatchers reported sighting an enemy submarine, which led to an unsuccessful aircraft search on 27/28 January 1943.

The troopship Wahine made calls on 29 March and on 11 April, embarking artillery units being redeployed to New Caledonia. N-Force was replaced at a reduced level by the 2nd Battalion Wellington-West Coast Regiment under Lieutenant Colonel Alan R. Cockerell, DSO.

On 18 June 1943 the NZ supply vessel Ronaki, lying off Kingston awaiting discharge, dragged her anchor and came to rest on a reef close to where Sirius was wrecked 153 years earlier. She was stripped of supplies and winched ashore where the hulk was broken up.

By September 1943 the strategic situation was such that a garrison was no longer necessary, except to operate and maintain the airfield, and on 8 December the garrison, now reduced to 478 men, embarked for Auckland. A small rear party remained until 11 February 1944, when command passed to the officer commanding the RNZAF station and Norfolk Island became an Air Force responsibility until the end of hostilities. A message of congratulations from Mr John Curtin, Prime Minister of Australia, in which he paid generous tribute to the behaviour and co-operation of the New Zealanders, farewelled the military garrison.

On 19 January 1944 two USN Landing Ships LSTs 359 and 392, coming from the Pacific Islands to New Zealand, took shelter under the island because of an impending storm. On 4 February a further LST 395 arrived, escorted by two RNZN Fairmiles. Later, on 16 July, two RNZN corvettes Arabis and Tui, accompanied by six RNZN Fairmiles, refuelled on their way to New Zealand. Post war, the whaling industry was resurrected at Norfolk Island using two ex-RAN Fairmiles as whale catchers.

The end of hostilities in the Pacific was officially announced on 15 August 1945, and on 20 August the Matai came from New Zealand with supplies and departed with service personnel whose period of enlistment had expired. The last change of command occurred on 28 August when Squadron Leader A. G. Lester RNZAF took command of the air station.

Some unexpected visitors

On 13 November 1945 Lieutenant Commander James A. Michener USN,8 a Public Affairs Officer who had served on Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides (Vanuatu) arrived on a four-day visit in connection with an official US War History. Norfolk Island features in his iconic Pulitzer Prize-winning masterpiece Tales of the South Pacific where he mentions an airfield built on the home of Bounty mutineers: ‘A lonely and lost speck in the midst of the Tasman Sea providing a vital air link between Australia, New Zealand and the Pacific Islands’.

Michener also notes that the removal of the Norfolk Island pines did not proceed without protest when the Admiral (Ghormley) says: ‘The Australian government has placed responsibility for the protection of Norfolk squarely on us. We can do what we damned well want to. But it is always easiest to exercise your power with judgement. Either you do what the local people want to do, or you jolly them into wanting to do what you’ve got to do anyway’.

A new Administrator, Mr Alexander Wilson, a prominent farmer and a politician, arrived in 1946. This appointment was criticised in some quarters, being seen as a return for political favours. In early January HMAS Bungaree arrived with stores and provisions for the civilian populace.

On 3 April 1946 the aircraft carrier HMS Vengeance and her destroyer escort HMS Armada called when on passage from Suva to Sydney. Both ships served briefly with the British Pacific Fleet but neither saw action during WWII. From 1952 to 1955 the then HMAS Vengeance served with distinction in the RAN.

There was no shortage of Vice Regal attention. After the cessation of hostilities in Europe, the Governor General of New Zealand, Sir Cyril Newall, made an official visit on 14 June 1945. On 27 March 1946 a two-day official visit by the Governor General of Australia commenced, as their Royal Highnesses the Duke and Duchess of Gloucester and retinue arrived from Sydney in three aircraft.

The curtain closes and a new beginning

Between 8 and 13 February 1946 a five-day auction of war surplus equipment was conducted and much appreciated by the local population. However, the transition to peacetime living was gradual and at the end of June 1946 there were still 60 RNZAF personnel on the island.

The New Zealand military presence on Norfolk Island, which began three years before the war ended, eventually came to a close some three years after the war’s end. On 4 July 1948 the RNZAF Station closed, its remaining personnel departed, and control of the air station passed to the Commonwealth of Australia’s Department of Civil Aviation. The war had unexpectedly awoken Norfolk Island and brought it into the 20th century with an airfield and air services connecting it to both Australia and New Zealand.

While no shots of anger were fired at or from the island, it played an important part as a ‘static aircraft carrier’ strategically placed in the midst of the Tasman Sea, where it provided a vital staging and refuelling station to hundreds of aircraft and a number of small ships servicing Allied forces in the Pacific theatre.

Visitors to Norfolk Island cannot escape its colonial past with the impressive remains of convict era stone buildings. On the other hand, they know little of the more recent past when the war came to Norfolk Island and when it became ‘New Zealand’s Aircraft Carrier’.

This forms a small but important story of the war in the Pacific.

Notes:

1 Draft Instructions for Governor Phillip 25 April 1787, Public Records Office, London.

2 The Reverend Benjamin Frances Brazier, Chaplain of Norfolk Island from December 1915 to October 1918, son of an English dentist and destined to follow in his father’s footsteps but studied law and later took holy orders.

3 As an 18-year-old at the end of WWII Gilbert (Gil) Hitch joined the RAN as a signalman serving in corvettes. After discharge he attended Teacher Training College and then joined the Commonwealth Department of Territories, later serving as Official Secretary to the Administrator of Norfolk Island. Gil married an islander and settled there.

4 The world’s largest ships Queen Elizabeth and Queen Mary had a drawback being the only ships afloat too big to navigate the Panama Canal. Each Queen was built to carry about 2000 passengers and 900 crew. As troopships they were each capable of carrying 5000 troops but at the request of the Americans this figure was raised to 8500 and later 10,000 with some instances of 15,000 being carried on shorter trans-Atlantic voyages.

5 The 2nd Battalion of the 162nd Regiment was commanded by Archibald Roosevelt, the son of President Theodore Roosevelt. Lieutenant Colonel Roosevelt was wounded in New Guinea.

6 There is no record of any naval ship departing for Norfolk Island in April 1942 but the well-known island trader SS Morinda under command of Captain S. (Stinger) Rothery departed Sydney for Norfolk on 14 April with 89 Army personnel. This 1971-ton vessel was requisitioned by the Shipping Control Board in December 1941 and may have received a coat of grey paint and some armament but retained her merchant crew.

7 The motor vessels Moamoa and Yochow were operating on the Australian coast when taken up from trade and allocated to the rapidly expanding United States Army Small Ships Section, then based in Sydney.

8 James Michener was a Quaker who became an English/History schoolteacher and later guest lecturer at Harvard. During WWII he enlisted in the USN and was commissioned to record naval history being mainly based in the New Hebrides (Vanuatu). His meticulous observations were turned into Tales of the South Pacific, his first of over 40 books, which won the Pulitzer Prize and was later turned into a hit Broadway musical.

References:

Beaglehole, J. C., The Life of Captain James Cook, A. & C. Black, London, 1974.

Brazier, B. F. (Reverend), Norfolk Island – a paper read to the Selden Society of Queensland on 25 October 1918 and later published by the Royal Historical Society of Queensland in 1920.

Campbell, Joseph, Norfolk Island and its Inhabitants, Joseph Cook & Co Printers, Sydney, 1879.

Charles, Roland W., Troopships of World War II, The Army Transportation Association, Washington, D.C., 1947.

Gill, G. Hermon, Australia in the War of 1939-1945: Royal Australian Navy 1939-1942, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1957.

Gillespie, Oliver A., The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939-1945 – The Pacific, Historical Publications Branch, Wellington, 1952.

Grube, Terence, Commemorative Events Program – Celebrating 75 years of Peace in the Pacific, Norfolk Island, August 2020.

Hitch, Gil., The Pacific War 1941-1945 and Norfolk Island, Self-Published, Norfolk Island,2005.

Hoare, Merval, Norfolk Island: A Revised & Enlarged History 1774-1998, CQU Press, Rockhampton, 1999.

Michener, James A., Tales of the South Pacific, The Macmillan Company, New York, 1950.

O’Neil, I. G. (Major), The 36th Battalion: A Record of Service of the 36th Battalion with the Third Division in the Pacific, Reed Publishing, Wellington, 1948.

Plowman, Peter, Across the Sea to War, Rosenberg, Sydney, 2003.