By Bob Hetherington

Originally Published in the Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM) Volunteers’ Quarterly newsletter ‘All Hands’, Issue 114 in March 2021.

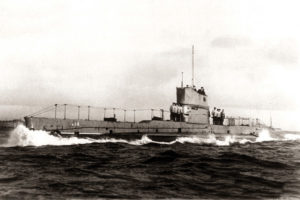

Many readers will know something of the AE2 story, how Lieutenant Commander Henry Gordon Stoker took his Australian submarine through the Dardanelles at the beginning of the Gallipoli campaign. Recently, out of the blue through the museum network, I was sent a link to an early voice recording of Stoker recounting his exploits. (Hear it for yourself via the link at the end of this story.) As I listened, my curiosity was fired and I set out to find more about this very colourful character

The trigger was in the first few seconds of this short recording, which was made some 40 years after the events described. As Stoker was born and grew up in Dublin, I was expecting an Irish brogue: how wrong could I be? Then there was the delivery: here was a man who had spent many years as an officer in the Royal Navy, who was renowned for his self-discipline and coolness in combat, yet his delivery was verging on theatrical. Another memory stirred: Stoker had a lifelong interest in acting and after the war became a stage and film actor.

Until now, my interest had been mainly in the military and naval side of the AE2 story … the record-breaking transit of AE1 and AE2 from the builders in Britain to Australia, and their departure from Sydney in 1914 to join the war in the northern hemisphere. I had

read accounts of the loss of AE1, the scuttling of AE2 in the Dardanelles and the capture of her crew.

Now my attention was drawn to the story of her remarkable captain and I began some research, starting with the excellent book Stoker’s Submarine, which gives insight into his character: “…fun-loving, irreverent and a bit of a dandy”. In his memoirs, Straws in the Wind, published after WWI, Stoker wrote: “With indulgent smile and jest on lip, I like to wave an airy hand and murmur: ‘Look at it all. What funny little folk we are – how seriously we take ourselves!’”

But there was another side to the man. When on Navy duty he was hard-working, with attention to detail, commanding lasting loyalty from his men. Today we might call him “a good communicator”, perhaps this gives a clue to his move later in life to a career as actor, playwright and stage director.

He was a keen sportsman … cricket, football and his favourite, polo. However, polo was a rich man’s sport, almost out of reach for a junior naval officer. In a “straws in the wind” moment, polo provided the link to his command of AE2: in 1913 the fledgling RAN was looking for crew for its new submarines, drawing heavily on the RN. Stoker was already serving on RN submarines and was aware of the situation. He later claimed that he had heard of a wealthy polo enthusiast in Sydney who was willing to pay people to play with him, so he immediately applied for command of one of the Australian boats. He was given command of AE2 and found his way to Sydney, but the outbreak of WWI put paid to his antipodean polo plans.

In April 1915 Stoker was assigned to take AE2 through the Dardanelles and disrupt Turkish shipping supplying Turkish troops at Gallipoli. This is the event covered in Stoker’s recording: with the skill of an actor he recreates the scene inside AE2 in the mind’s eye of the listener … the sounds of the mine tether cables scraping along the submerged hull, the terror of the uncontrolled dives, the relief when they surface.

After the scuttling of the boat and capture of the crew there were years of suffering and privation in Turkish POW camps, including the deaths of a number of his crew. During this period Stoker’s optimistic character and positive outlook were evident. Some “straws in the wind” moments led to (unsuccessful) escape attempts. He tried his hand (successfully) at amateur theatricals when he wrote, sang and played for the “shows” that lightened the tedium of captivity for his fellow prisoners. One of them later wrote of “a cheerful and lovable Irishman and an optimist always”.

When war ended Stoker returned to England to serious problems in his personal life and Navy career. He divorced his wife and lost contact with his two daughters. He transferred back to the RN but felt that years in captivity had cost him promotion relative to his peers. Barely two months after his return he was given command of a new K Class submarine and within a year was made commander. He found that attitudes had changed, and relations with his officers and men were not as effective as before. The K Class developed a reputation for unreliability and Stoker’s boat was involved in a collision with another Navy vessel. Although largely exonerated, he applied for transfer out of submarine service.

While waiting for a posting, another “straw in the wind” led to a chance meeting with the stage manager of a leading London theatre and the offer of some acting work. Stoker declared his situation to the Navy, where the idea of a serving officer moonlighting on the stage raised eyebrows but there was acceptance and an undertaking to give him plenty of warning of any impending posting. He delightedly took on his first professional acting role in a successful West End play and for a period was receiving two pay packets: one from the Admiralty to Cdr Stoker and one from the Ambassadors Theatre to Hew Gordon, his new stage name. Unexpectedly and at short notice came a posting as captain of an RN cruiser, posing a huge dilemma: the sea or the stage? He applied for six months’ leave on half pay, remained in the play and pondered his future.

Stoker’s contacts in the theatre were guarded about his prospects of making a new career, so he was facing a calculated risk: frustration but security in the peacetime Navy or an appealing but uncertain life on the stage. In late 1920, at the age of 35, he requested to be put on the Navy retired list. The die was cast; the stage had won over the sea. The transition was a wrench. His formative years and his whole adult life had been in the Navy in peace, war and captivity. He later wrote: “I doubt if human wives and sweethearts ever realise the strength of the rival they have to fight in winning and keeping a sailor lover.”

The stage provided some early minor successes, with character roles in West End plays attracting favourable comment from the critics. The roles grew and later he found himself playing alongside a beautiful young actress called Dorothie Pidcock. Romance blossomed and in 1925 they married in a stylish ceremony with Stoker in full naval uniform.

By this time his career was expanding in both literary and theatrical directions and he published Straws in the Wind, an account of his naval career, which ran to several editions. Because of the Gallipoli story it sold well in Australia, where not surprisingly AE2 was known as an Australian submarine (also not surprisingly, in Britain it was known as a

British submarine).

Stoker toured with a Galsworthy play to New York where the local press hailed him as “the man who drove the first Allied submarine under the minefields of the Dardanelles” and described him as “a typical Englishman”. We don’t know if Irish-born Stoker was offended by this; perhaps he would have

Stoker toured with a Galsworthy play to New York where the local press hailed him as “the man who drove the first Allied submarine under the minefields of the Dardanelles” and described him as “a typical Englishman”. We don’t know if Irish-born Stoker was offended by this; perhaps he would have

shrugged it off with a characteristic raising of an eyebrow. Back in London he took on his most famous stage role in Journey’s End, set in the closing years of WWI, playing against a youthful Laurence Olivier.

Soon he turned his hand to playwriting, collaborating with another former submariner in Beneath the Surface, which featured a mock submarine interior as a set. The new medium of radio beckoned and Stoker made broadcasts with the BBC describing the Dardanelles mission and his escape from a Turkish POW camp. Two film appearances followed, evoking his Navy experiences; in on e of them a young John Mills also appeared.

The scenario he had found unimaginable when he decided to leave the Navy now shattered his civilian life: a second world war and a recall to active service. Now in his 50s, Stoker spent the war years in Britain in a variety of roles, eventually finding himself close to the highest level planning for D Day. After the war he returned to acting, but after five years of real life drama the theatre had lost its appeal. Television was opening new horizons and, always up for something new, he wrote for a hit drama series, Deep Waters.

In later life Stoker mused to friends that his lifelong aim “to be a good allrounder” had given him two rewarding careers but had not led to the top of any profession and the corresponding financial rewards. He and his wife maintained an active social life with a wide range of friends and acquaintances across the British social spectrum. In 1948 he enjoyed what he described as “one of the most pleasant days I ever spent in my life” as a guest of George VI. While playing cricket he was in at bat and facing the King’s bowling. He said, “Sir, please remember that I was a shipmate with your grandfather”, raising a laugh all round.

Henry Hugh Gordon Stoker died in London in 1966 at the age of 81. Before we end the story perhaps we should listen again to his voice. This time we may not be surprised at the cultured accent, professional delivery and hint of theatricality: Link

Sources:

Brenchley, Fred and Elizabeth, Stoker’s Submarine, ATOM publisher, 2001

Stoker, H.G., Straws in the Wind, Herbert Jenkins, London, 1925

Nga Taonga Sound & Vision (New Zealand)

National Film and Sound Archive (Australia)

www.aveleyman.com (for photographs of Stoker’s film roles)