By Angus Britts

The Japanese air attacks against Port Darwin in the forenoon of 19 February 1942 were a salient moment in Australia’s modern history. For the first time the nation’s shores had been assailed by a hostile military power, with those present in Darwin that day being subjected to the terrifying realities of virtually unopposed bombing and strafing. Hundreds of lives were lost, numerous ships sunk or damaged, and heavy damage inflicted upon the town itself, its port facilities, and the adjoining RAAF aerodrome. As an editorial in The Sydney Morning Herald the following day proclaimed, “We may as a people have needed some such grim development to awaken us finally to the realities of war. Too many in our midst have trusted despite all warnings that the storm might yet somehow pass Australia by.”

Yet within the collection of published accounts, eyewitness recollections, and forensic analysis of both the raid and the events which followed in its immediate aftermath, one important aspect has been largely obscured. The nature of the strike itself, conducted by elements of the Imperial Japanese Navy’s (IJN) First and Eleventh Air Fleets, represented a notable milestone in the overall history of naval air aviation. For the first and only time in the course of naval air operations during the Second World War, a co-ordinated strike was carried out by both carrier-borne and land-based elements of a naval air force against a single target. In this respect, the bombing of Darwin marked the ultimate concentration of Japan’s formidable aerial prowess that had been assembled in the years following the Great War, and which was negligently dismissed as second-rate by so many Western military experts prior to the events of 7 December 1941. The purpose of this article is to provide an overview of the evolution of this remarkable capability, as well as the circumstances behind its eventual defeat in the Asia-Pacific theatre of operations.

In common with the United States, Japan did not seek to assemble an independent air arm in the aftermath of the Great War. Due to the prevailing nature of Japanese inter-service politics such an eventuality was next to impossible thanks to the deep cultural divide, and frequent open animosity, between the Japanese army and navy. The Imperial Japanese Army Air Force (IJAAF) would eventually be contrived as a primarily ground-support focused air arm, heavily influenced in design philosophies by the Italian Regia Aeronautica in particular. An early benefit for Japanese naval aviation came through a range of technical support supplied from the British Air Ministry in the 1920s, which provided Japan with, amongst other specialities, vital technical knowledge in the fields of aircraft carrier construction and aero-engine design. The post-war decades were a formative period for naval aviation per se as the Great Powers (minus Germany) grappled with how best to incorporate the aeroplane into their respective fleet environments. Yet while period advocates of air power such as William ‘Billy’ Mitchell, Giulio Douhet, and Hugh Trenchard, all recognised the future dominant roles of aircraft in modern warfare, by the end of the 1920s very few naval experts yet perceived the supplanting of the battleship as the preeminent fighting force at sea.

Along with the Royal Navy, the IJN was an original pioneer in the sphere of the aircraft-carrier. In 1922 the Japanese fleet welcomed the light carrier HIJMS Hosho (‘Flying Phoenix’), the second such vessel to be constructed as a carrier from the keel up. At just 7,470 tons Hosho carried less than a

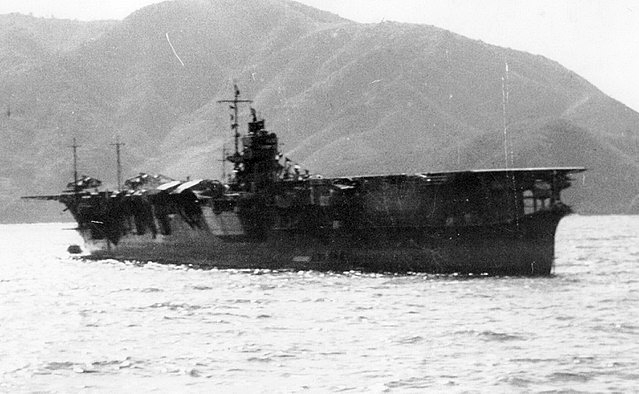

dozen aircraft as originally configured, but she was soon joined by two much larger compatriots: the 36,500-ton Akagi (‘Red Castle’) and the 38,200-ton Kaga (the name of a former Japanese province). Both Akagi and Kaga were conversions – the former from a battlecruiser, and the latter from a battleship. These ships were the equals in size to the American USS Lexington and Saratoga, and could carry up to 90 aircraft each. In 1933 the IJN’s First Air Fleet was increased with the addition of the 10,600-ton light carrierRyujo.

(‘Heavenly Dragon’), and was further expanded in the mid-1930s through the 15,900-ton Soryu (‘Deep Blue Dragon’) and the 17,300-ton Hiryu (‘Flying Dragon’).

HIJMS Soryu

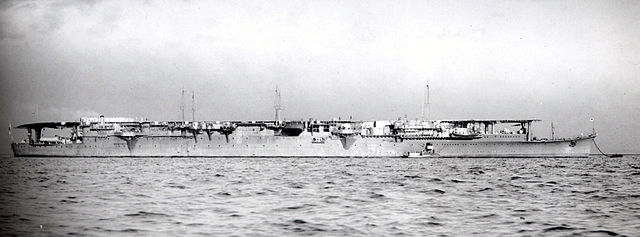

Prior to December 1941 two further carriers were commissioned: the 26,675-ton sisters Shokaku (‘Soaring Crane’) and Zuikaku (‘Happy Crane’). At 11,260 tons the two light carriers Shoho (‘Happy Phoenix’) and Zuiho (‘Lucky Phoenix’), both converted fast oilers, were available for service in early 1942. Between them these ten ships could deploy in the vicinity of 600 aircraft.

HIJMS Shokaku

HIJMS Zuiho

But the late 1930s the IJN had taken impressive steps to ensure that its growing carrier fleet was equipped with a formidable modern air striking arm. Much of the impetus for this arose from the appointment of the future CIC Combined Fleet, Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku, as head of the IJN’s aeronautical technical division in 1932. His policy of promoting advanced monoplane aircraft designs resulted in the introduction of the Type 96 fighter (Allied reporting name: ‘Claude’) and the Type 97 attack bomber (‘Kate’) in 1936.

They were joined in 1939 by the Type 99 dive-bomber (‘Val’). With an elliptical wingspan, fixed spatted undercarriage, and a top speed of 270mph, the Mitsubishi-built Claude proved to be highly successful when eventually deployed in the Sino-Japanese war. Equipped to operate either as a level/dive-bomber or torpedo bomber, the Nakajima-built Kate was superior to both its British and American contemporaries in virtually all respects, while the Aichi-built Val enjoyed better handling characteristics than its overseas competitors. Similar to the Claude, the Val sported a distinctive elliptical wingspan and fixed spatted undercarriage.

Then in 1940 the introduction of the latest creation from the brilliant Japanese designer Horikoshi Jiro provided the IJN with its most dominant aerial weapon in the form of the Type 0 (‘Zeke’) fighter. A top speed of 340mph and a phenomenal range of 1,595 miles combined with heavy armament and superb manoeuvrability enabled the Zeke to subsequently outperform the majority of foreign land-based and carrier-borne fighters then in service.

Mitsubishi Type 0 Fighter

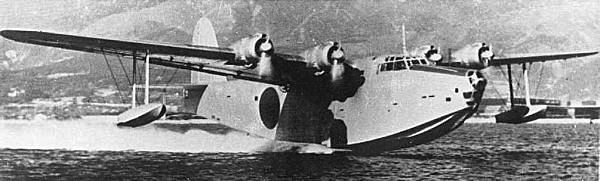

Other Japanese naval air branches were not neglected. The Combined Fleet’s cruisers, battleships, seaplane-carriers, and land-based squadrons were liberally supplied with various types of seaplanes, most notably the Type 0 (‘Jake’), which presented the IJN with a highly effective reconnaissance capability. These were augmented by two large flying-boat models, the Type 97 (‘Mavis’), and the Type 2 (‘Emily’), the latter acknowledged by many aviation experts as the best aircraft of its type in World War II. As for the land-based element of the striking force, two twin-engine designs were available in quantity by December 1941. First introduced in 1936 the slender Type 96 attack bomber (‘Nell’) proved its mettle in the Sino-Japanese conflict by carrying out long-range bombing missions against targets in China when flying from Japan’s home islands. It was joined in 1940 by the Type 1 attack bomber (‘Betty’). Both aircraft were equally proficient when operating with bombs or torpedoes, and their ranges, each of which exceeded 2,000 miles, would only be bettered by the massive American B-29 bomber. Though lightly equipped with defensive armament, the Nells and Bettys enjoyed the welcome protection afforded by Zekes assigned to the five air flotillas of the Eleventh Air Fleet.

Kawanishi Type 2 Flying Boat

Mitsubishi Type 96 Attack Bomber

In similar fashion to the experience of their contemporaries in Britain and the United States, the proponents of Japanese naval airpower spent much of the 1930s engaged in debate with those in the IJN who still favoured the cause of the battleship as the paramount naval weapon. Japanese naval doctrine was squarely based upon the doctrine of the ‘Decisive Battle’, first proposed in the early 1900 within the publication Kai Sen Yomu-Hei (“Essential Instructions on Naval Battles”). As adopted in the 1930s this strategy called for a great naval engagement between the Japanese and American fleets to the east of the Marshall Islands, whereby the US Pacific Fleet would be challenged after it had been first subjected to attrition from land-based aircraft and submarines. While aircraft-carriers were to initiate the fleet confrontation, the IJN’s battleships would strike the final blow. Within Japanese naval politics the so-called ‘battleship faction’ wielded considerable influence, and it was thanks to such politicking that the construction of the giant Yamato-class super-battleships was authorised from 1936 onwards. Yet advocates for air power such as Yamamoto, Ozawa Jisaburo, and Inoue Shigeyoshi, contended that the battleship was obsolete in the presence of the aeroplane, and continued to evolve tactics which reflected this fact. Their efforts were eventually rewarded in April 1941 with the reorganisation of the First Air Fleet into a striking force comprised of the six largest Japanese carriers. The formation became known as the Kido Butai (‘Mobile Force’), and in the opening months of the Asia-Pacific conflict it would proceed to terrorise the Allied navies across the various oceans and seas from Hawaii to Ceylon.

Yamamoto and his colleagues kept a weather eye on events in Europe well prior to Japan’s attack against Pearl Harbour. The raid executed by British carrier-borne torpedo-bombers against the Italian fleet at Taranto in 1940 confirmed their belief that a similar attack could be performed against the US Pacific Fleet at Hawaii, thus allowing for a major re-appraisal of Japanese naval strategy. If the bulk of the American battleships and aircraft-carriers could be neutralised via a massive pre-emptive airstrike at the outset of hostilities, Japan’s conquest of South-East Asia would be undertaken without significant interference. Likewise, Yamamoto believed that the Eleventh Air Fleet’s long-range bombers could perform similar neutralising attacks against American and British land-based air assets in the Philippines and Malaya respectively, and sink any of the Royal Navy’s capital ships basing at Singapore. Thus, plans were drawn up for major strikes to be launched from airfields on Formosa, and in southern Indo-China, to achieve these separate aims. Precise co-ordination and decisive results were necessary. Possessing only a limited domestic stockpile of oil for their initial offensive operations, the Japanese could not afford to be profligate in the performance of naval activities prior to the capture of the vital wellheads and refineries within the Dutch East Indies. As such a war of attrition in this period was to be avoided at all costs. Fortuitously for the Japanese, forthcoming events were to dictate otherwise.

The astonishing speed with which Japan’s aero-amphibious campaign achieved success in the first five months of war was due to a number of factors. These included the general unpreparedness of the Allied armed services, the underestimation of Japanese airpower on the part of senior Allied commanders, and the precision with which Japan’s naval air arm in particular executed its various strikes. At sea, the First Air Fleet’s carriers wreaked havoc at Pearl Harbor, Wake, Rabaul, Darwin, Tjilatjap, Colombo, and Trincomalee. With the notable exception of the air operations undertaken during the course of Operation C in the Indian Ocean in early April 1942, all of the other strikes were accomplished with the benefit of surprise. An appreciation of the lethal power wielded by Vice-Admiral Nagumo Chuichi’s command is illustrated by the sinking of the British cruisers HMS Cornwall and Dorsetshire to the southwest of Ceylon on 5 April 1942 where the attacking Vals achieved a bombing accuracy of approximately 90%, the highest such figure recorded at sea in World War II. Only the absence of the USN’s carriers from Pearl Harbour, and the failure of Nagumo’s reconnaissance aircraft to locate the bulk of the British Eastern Fleet in the vicinity of Ceylon, spared the respective Allied navies from utter calamities.

Ashore, the performance of the Eleventh Air Fleet matched the exploits of the IJN’s carrier spearhead. On the opening day of hostilities elements of the 21st and 23rd Air Flotillas decimated the ranks of the American Far East Air Force at Clark Field on Luzon, with a similar result achieved by the 24th Air Flotilla when it well-nigh wiped out a recently-deployed US Marine fighter squadron at Wake Island. Further westwards that same day, aircraft from the 22nd Air Flotilla inflicted heavy casualties upon RAF and RAAF squadrons at aerodromes in northern Malaya. The on 10 December, the 22nd shocked the Royal Navy when eighty Nells and Bettys predominately armed with torpedoes sank the British battleship Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser Repulse off the east coast of Malaya. Thereafter the 21stand 23rd Air Flotillas, flying from captured airfields in Borneo and the Celebes, supported the invasion of Java with raids against Allied shipping and land bases. In concert with the air group from the light carrier Ryujo, these land-based elements persistently harried the two hastily-assembled ABDA (American-British-Dutch-Australian) surface forces prior to the eventual disintegration of Admiral Dorman’s squadron in the battle of the Java Sea on 27 February 1942. Eight days before this blow was struck, it had been Port Darwin’s turn to experience the full fury of the Japanese aerial onslaught.

As the major point of supply and reinforcement of the Allied presence in the Dutch East Indies, Darwin presented as a necessary target to be neutralised so that the final invasion of Java could proceed unhindered. To mount the attack, four carriers (Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu) and aircraft from the 21st and 23rd Air Flotillas based in the Celebes were assigned. On the morning of 19 February eighty-one Vals, Kates and Zekes from the carriers were launched, along with fifty-four Bettys and Nells from the captured airfield at Kendari. Though warnings were received from forward observers, no alarm was sounded at the port until the carrier aircraft were directly overhead. After making short work of four P-40 fighters patrolling over the town the Japanese aircraft proceeded to blitz the target area, sinking three naval and five merchant ships, with three more merchants beached and nine vessels otherwise damaged. Shortly thereafter the bombers from Kendari arrived to devastate the RAAF aerodrome, destroying or damaging more than twenty aircraft on the ground. At least 240 people were killed and more than 150 wounded. The combined airstrike succeeded in generating considerable panic amongst the population and local military units with an exodus of service personnel and civilians to the south, and a belief amongst many that the raids were a precursor to Japanese landings in the vicinity.

These strikes against Darwin represented the noontide of Japanese air supremacy in the Pacific war as a similar co-ordinated carrier/land-based exercise was not thereafter to be repeated, nor did any subsequent attack executed by Japan’s naval air arm inflict such extensive damage. In this respect the attack was the most decisive of its kind since the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Following its successful operations in the Indian Ocean two months later which forced the withdrawal of the bulk of the British Eastern Fleet to East Africa, the First Air Fleet was redeployed to the Pacific along with much of the strength of the Eleventh Air Fleet, and from thereon in the fortunes of both arms began to decline. A pyrrhic tactical success at the Coral Sea in May preceded the disaster for Japan’s carriers at Midway, and afterwards the grim cycle of attrition in the Solomons campaign and New Guinea which wore down Japanese airpower. In an attempt to claw back the initiative, Yamamoto redeployed much of his carrier-borne air strength to land bases for a series of massive strikes against targets in both New Guinea and the Solomons in April 1943. These proved to be costly failures which resulted in heavy casualties amongst the carrier air groups involved, and ultimately resulted in Yamamoto’s death on 18 April 1943 when his command aircraft was surprised and shot down by long-range P-38 Lightning fighters over Buin. More disastrous losses were suffered in American carrier raids against Truk in February 1944, which were a precursor to the catastrophe for Japanese naval aviation at the Philippine Sea engagement in June of that year where over 400 carrier and land-based aircraft were destroyed in what became known as the ‘Great Marianas Turkey Shoot’.

The subsequent decision by the IJN to increasingly adopt kamikaze tactics so as to forestall the USN’s remorseless advance towards Japan itself reflected the almost complete disintegration of Japan’s aerial capability to repel the Americans by conventional means. Much of the responsibility for this collapse lay squarely at the feet of the Japanese themselves. In seeking to wage a quick decisive war that nation’s armed forces had placed all their faith in the doctrine of the offensive, which had serious implications for the waging of war as a whole. In the air naval operational sphere, the use of over-elaborate fleet tactics (at Midway in particular) robbed the First Air Fleet of its most potent asset, namely the ability to conduct operations as an independent striking spearhead, utilising speed and stealth to surprise and overwhelm its opponents. The successes achieved at Pearl Harbour, Darwin, and in the Indian Ocean were never to be replicated, and when the Kido Butai did sortie again in force at the Philippine Sea, its massed attacks against the American 5th Fleet were easily repulsed by decisive concentrated defensive firepower in the form of the Grumman F-6 Hellcat fighters. Conversely for the USN, imitation proved to be the sincerest form of flattery as from June 1943 onwards the large carrier spearheads employed by the 5th Fleet succeeded in laying waste to bases in the Caroline, Marshall, and Mariana Island groups that constituted the vital Pacific Island shield for the Japanese homeland.

Behind the front lines Japan’s overly obsessive concentration upon offensive naval means proved to be equally disastrous in a number of key respects. The IJN had gone to war reliant upon a relatively small cadre of highly trained pilots and aircrew. In assembling this group, no provision had been made for adequate numbers of trained reserves. Thus, when casualties began to be taken in earnest, an accompanying lowering of performance was noticeable. Training programmes for Japanese navy and army aviators were also compromised by a growing shortage of fuel, and far fewer qualified instructors than were available within the various Allied training establishments. Compounding these difficulties was the inability of Japan’s aero industry to recognise, until far too late, the lethal flaw in its policy of concentrating upon range and aircraft performance. The trade-off was the distinct lack of protective armour and basics such as self-sealing fuel tanks, with the result that the Zekes and Bettys in particular were highly vulnerable to even small-calibre fire. Another major drawback became the inability of Mitsubishi and its contractor partners to replace the Zeke with the considerably more powerful A7M ‘Sam’, which never reached operational service primarily due to delays caused by problems with its high-performance engine. Thanks to the backing of their massive industrial apparatus, the Americans were able to field exceptional second-generation wartime fighters in the form of the Hellcats and F4U Corsairs which eventually decimated the aging Zekes. Nor was the IJN able to make good its losses in large carriers, only one of which (Taiho) participated in the battle of the Philippine Sea where it was sunk by an American submarine.

In a protracted conflict against the might of American productive capacity the Japanese war machine was ultimately doomed, though fanatical resistance eventually resulted in the decision by President Truman to employ atomic weapons against Hiroshima and Nagasaki in order to circumvent the need for an amphibious invasion of Japan itself. Though the period of naval air dominance at sea prior to the atomic and guided-missile age proved to be relatively brief, the IJN had led the way with the use of the aircraft-carrier as a spearhead weapon. The combination of carrier-borne and land-based air assets provided the Japanese with a highly capable offensive instrument which demonstrated the full range of its capabilities over Darwin on a February morning in 1942. In many respects its eventual defeat can been viewed as a by-product of this and other early successes, yet regardless of the eventual outcomes, Japan’s forward strides in the evolution of naval aviation authored a most significant chapter in the history of modern naval warfare.

Select Bibliography

Britts, A. Neglected Skies: The Demise of British Naval Power in the Far East, 1922-42. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2017.

Britts, A. A Ceaseless Watch: Australia’s Third-Party Naval Defense, 1919-42. Annapolis, Naval Institute Press, 2021.

Brown, E.M. Duels in the Sky: World War II Naval Aircraft in Combat. Annapolis MY: Naval Institute Press, 1988.

Burton, J. Fortnight of Infamy: The Collapse of Allied Airpower West of Pearl Harbour. Annapolis MY: Naval Institute Press, 2016.

Gill, G. Hermon, Royal Australian Navy 1939-1942. Adelaide: The Griffin Press, 1957.

Gillison, D. Royal Australian Air Force 1939-1942. Adelaide: The Griffin Press, 1962.

Goldstein, D.M. & Dillon, K.V. (eds.). The Pacific War Papers: Japanese Documents of World War II. Dulles, VA: Potomac Books, 2004.

Okumiya, M., Horikoshi, J., & Caiden, M. Zero! The Story of Japan’s Air War in the Pacific 1941-45. New York: Ballentine Books, 1973.

Macintyre, D. The Battle for the Pacific. London: William Clowes & Sons Ltd, 1966.

Marder, A.J. Old Friends, New Enemies: The Royal Navy and the Imperial Japanese Navy Volume I: Strategic Illusions, 1936-1941. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981.

Stille, M.J. Imperial Japanese Navy Aircraft Carriers 1921-45. Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2005.

Van der Vat, D. The Pacific Campaign: The U.S.-Japanese Naval War 1941-1945. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1991.