By John Ingram

The following personal reflection by Commander John Ingram OAM RAN RTD describes his experience and observations of the fateful collision between HMA Ships Melbourne and Voyager on the night of 10 February 1964. On this day John was both the Duty Fleet Staff Officer (DFSO) and Officer of the Day (OOD). At this time HMAS Sydney was the Flag Ship. This paper is extracted form Chapter 14 of his biography, ‘The Tumbling Dice of Circumstance’.

I stepped onboard the former aircraft carrier HMAS SYDNEY, newly designated “Fast Military Transport” (A214), alongside the Cruiser Wharf before Colours at 0800 on New Year’s Day 1964 complete with my sea chest and sword. My commanding officer was Captain W.A.G. Dovers DSC. Being a public holiday and with the ship’s company reduced to the bare minimum over the leave period, led me to believe I’d have time to settle in to my cabin, get to know the layout and routines of the ship and ease myself into a new job. The Command, however, had other ideas for I learned I was OOD that very day and would be starting in my new job as Section Officer (Material) on the staff of the Chief Staff Officer (Administration) the next day. That day I also proudly wore two stripes.

As he’d done at CRESWELL in 1958, by rapidly and effectively converting a rundown base into a fine Naval College, Captain Dovers had brought the SYDNEY out of retirement and re-commissioned her with a minimal crew. Her role was to be the Navy’s primary training ship for both sailors, Reservists and junior officers. However, the need arose in 1963 to transport elements of the Australian Army to Borneo, complete with all their equipment. SYDNEY, at short notice and without the proper equipment fitted, had taken on this operational logistics role.

A further complication arose in late 1963 when the Flag of FOCAF, the Fleet Commander, was transferred from the MELBOURNE to the SYDNEY while the former underwent maintenance. In January 1964 MELBOURNE, began “working up” off the coast with her air squadrons before sailing for a scheduled five months Far East deployment. This transfer of the Flag meant RADM Becher and staff of 20 officers and sailors were now in the SYDNEY with me, as the most junior officer on his staff.

RADM Otto Humphrey Becher CBE DSO DSC and Bar was the Flag Officer Commanding (FOCAF) with Captain W.A.G. Dovers DSC as Chief of Staff. Months earlier while on a training cruise in Great Barrier Reef waters five junior officers under training were lost, presumed drowned, when a 27-foot whaler capsized at night while on an expedition. This tragic loss resulted in courts martial, including the trial and conviction of Captain Dovers (later quashed). This incident had cast a sombre spell over the ship.

Although my posting read “SYDNEY additional for Fleet Staff” I’d imagined I’d be borne on the ship’s books but have no “ship duties”. How wrong this was to be! As a result of the chronic shortage of officers in the ship’s complement, I found myself watch-keeping in both harbour and at sea. In reality this meant in harbour combining both the Duty Fleet Staff Officer (DFSO) role with that of the ship’s DXO/OOD, while at sea, watch-keeping in Damage Control Head Quarters (DCHQ) deep in the bowels of the ship where the noise was extreme and the heat emanating from the ship’s boilers and machinery spaces sapped one’s strength to near exhaustion. These would be a four hour shift most nights at sea, all on top of one’s normal workday as a staff officer.

It seems preposterous in the 21st century, but in 1964 naval correspondence was almost all by typed letter. Signal traffic was essentially teletype but slow and time consuming. Phone lines were few, insecure and costly. Only senior officers were authorised to make “trunk line” STD calls. Naval forms were used for matters of a repetitive nature, such as performance reports on officers and sailors. On Fleet staff only the three departmental heads could sign for the admiral as Fleet Commander. Letters to Navy Office were invariably addressed to the Secretary, Australian Commonwealth Naval Board and fell into one of two categories, official and formal. The introductory paragraph would read “Be pleased to lay before the Naval Board the results of………..” or a variation thereof. The finale would be “I have the honour to be, Sir, your obedient servant”. This submissive style ensured we knew our place in the naval bureaucratic hierarchy. Naval letter writing had not really changed since the days of Samuel Pepys!

I had one particularly onerous secondary task, that being in charge of FOCAF’s “Charge or Classified Books” (CB) account. This sounds straightforward but both my predecessor and successor were subjected to boards of inquiry relating to alleged “mismanagement” of this seemingly innocuous account. “Charge Books” comprised a library of classified publications ranging from Confidential to Top Secret including AUSTEO (Australian Eyes Only). My role was to keep all publications current by ongoing manual amendment action. This involved painstaking “cut, paste and edit” of intelligence reports and tactical publications called for by staff officers in the execution of their duties: a thankless task of infinite detail while locked away in a tiny compartment with fetid air.

Oftentimes in harbour I’d surrender precious recreational time, including week-ends, to ensure the account was correct in all respects. Accountability was mine alone for the year I was responsible. At the time the national and military situation between Australia and Indonesia was deteriorating fast as President Sukarno had embarked upon “Konfrontasi” with Malaya/Malaysia and Singapore, resulting in the invoking of the five-nation security agreement to protect Allied interests in the region. A significant amount of intelligence material was being received onboard in a steady stream and it all had to be actioned on receipt. But this was a “collateral duty” to be undertaken in my “spare time”!

FOCAF’s staff was split into three sectors namely Operational, Technical and Administrative. While my role as Section Officer (Material) in 1964 was “under” the Chief Staff Officer (CSO) (Administration), my work was actually “technical”, so I acted as the administrator/co-ordinator for the CSO (Technical).

1964 was “annus horribilus” for the RAN for reasons I’m about to mention. “Logistics” was not a word in use in either industry or the Navy. Working for CST (Technical) gave me an “Edison lightbulb moment” in that linking Supply and Engineering could lead to a mutually beneficial “marriage” and cultivate what would ultimately be known as “operational maritime logistics”. But here I’m getting well ahead of myself.

The third sector of FOCAF’s staff was the Seaman/Executive branch who managed the fleet operational matters. Directly beneath the Admiral was his Chief of Staff (COS) who doubled as the ship’s commanding officer. The next tier down was the Fleet Operations Officer (FOO) who had at his disposal an experienced and highly qualified officer from each of the Executive Branch specialisations: Navigation, Gunnery/Weapons, Aviation, Communications and Anti-submarine warfare. I had daily interaction with these officers in normal course of duty, in my capacity as “Charge Books” officer and finally as a watch-keeping officer in harbour and at sea. It was an intimate “team approach” and, as the most junior officer on the staff, was full of challenges for me. One learnt quickly or faced the consequences!

Operationally, 1964 did not begin well for the Fleet Commander. The first incident involved a yacht which disappeared off Sydney in January. It was later to be claimed the then duty destroyer, the YARRA, had been too slow to sail to locate the stricken vessel. This incident had received a great deal of media attention as a relative of a politician was one of those lost.

The second incident involved SUPPLY, the fleet oiler then in dockyard hands at Garden Island and hence “non-operational” pending completion of her refit and work-up. Late on that January day SUPPLY was undocked and moved by tugs to the carrier berth. Dockyard personnel had failed to close a critical valve and during the night, while embarking potable fresh water, she sank to the harbour bed leaving her upper deck and superstructure visible. It took many of Sydney’s fire brigades’ hours to pump SUPPLY dry. With her at such a visible berth the media had a field day. This incident was a bad omen for much worse was soon to follow. SUPPLY, as the RAN’s sole underway replenishment ship, had to be repaired very quickly as she was critical to the Navy’s operational commitments in SE Asian waters, commencing with the MELBOURNE’s deployment, along with her escorts, in just a few weeks.

In 1964 naval dockyards were at their nadir with the Navy held captive by militant unions, especially the Painters and Dockers whose antics, aided and abetted by some state and federal politicians, were a public disgrace. The eventual outcome was for the federal government to sell off the naval dockyards as the all-powerful unions constantly held the Navy to ransom; a sad, sorry state of affairs indeed.

10 February 1964 is a day I’ll never forget. I’d spent the previous week-end at Kiama with my fiancée’s parents discussing wedding plans. On that Sunday morning we’d observed VOYAGER, under the command of Captain D.H. Stevens, in company with KIMBLA, the latter towing a Williams Battle Practice target. I’d explained to my hosts VOYAGER was “working up” prior to deploying to the Far East and had been engaged in a “throw off” shoot in the naval exercise area. That evening I returned to Sydney and repaired on board the SYDNEY.

At 1600 on 10 February I, as the Duty Fleet Staff Officer (DFSO) and SYDNEY’s OOD (Officer of the Day), reported to the Operations Room for briefing by the FOO/FOA, this being only my third time in this responsible position. I was keen to note the disposition of all ships. I also need to explain this key point: in 1964 “command of the fleet” was different from that which pertained later. In 1964 “minor war vessels” came under the command of either FOICEAA (Flag Officer in Charge East Australia Area) or regional/State based commanders such as NOIC-JB (Naval Officer in Charge Jervis Bay).

It was a complicated arrangement which worked in an administrative sense but operationally was to prove a mess. NOIC-JB, CO HMAS ALBATROSS/NAS Nowra (the RAN’s operational aviation base and home of the Fleet Air Arm) and the aforementioned KIMBLA (a “minor” war vessel), were examples of commands which didn’t come under the Fleet Commander. All three are relevant to the account about to unfold. If the Fleet Commander wished to involve one of the Area Commanders’ assets, such as helicopter, airfield or personnel, he had to seek prior approval.

The Navy was a collection of tightly managed “fiefdoms”. Outside normal working hours the problems magnified as communications in 1964 were largely insecure and landline based. Ships alongside would rarely have four telephones. Those at Sydney Harbour moorings commonly limited to a single phone line.

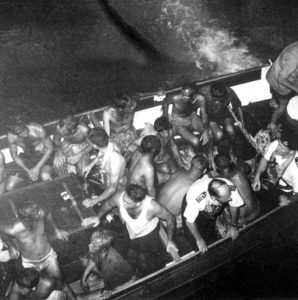

A rather prophetic photo: but if you wish for peace one must prepare for war (“Si vis pacem, para bellum”) was the Roman adage

On completion of the operational briefing my head was full of ship dispositions, weather reports, defect reports etc. FOO’s last words to me as he descended the brow of the Sydney at 1700 were “I want a quiet night; we’ve had a pretty tough time of late; I don’t want any more incidents. I’ll be at home: only contact me in the event of something serious.”

I then reported to the CO/Chief of Staff in his day cabin, the newly joined Captain Stevenson. “HD” as he was known, was a very safe pair of hands in navy parlance. If something needed fixing or playing safe, “HD” was the “go to” man. For example, when the RNZN cruiser and flagship ROYALIST, had a gunnery incident off Jervis Bay causing consternation ashore when wayward shells landed near Huskisson, and another serious incident involving a boiler “melt-down”, “HD” had been seconded to take command and restore confidence in the RNZN.

“HD” knew nothing of me and my knowledge of him was by reputation alone. I knew he’d been the chief cadet captain at the RAN College, had been awarded “blues” for everything imaginable, was the son of a former Bishop of Grafton, smoked a lot and swore like the proverbial trooper. I had a confused assessment of my CO at this very early stage but was, nevertheless, in awe of his achievements.

“HD” explained he’d be dining ashore that evening farewelling a friend returning to England via a P and O liner then at Circular Quay, adding the name and phone number of the restaurant was in his harbour cabin safe. Only in extreme circumstances was he to be disturbed and that via the “Maître D”. He then handed me his safe combination in a sealed envelope. I escorted him to the gangway where he was piped over the side. By then it was 1900; I did formal evening rounds of the SYDNEY inspecting all mess decks, galleys etc and exercising the fire and emergency party.

With SYDNEY in her home port and preparing to sail in a few days there were very few officers onboard that evening. Due to my OOD duties I was late in dining and around 2050 I went into the Wardroom ante-room to enjoy a coffee and read the signal traffic. My direct boss, Captain Fred Irvine, enquired as to whether I’d join him in a drink. I explained I “had the deck” (meaning I would not drink alcohol) and he fully understood. We were having a quiet chat together standing at the bar when a young able seaman TO (Tactical Operator) burst breathless into the Wardroom ante-room thrusting a hand-written note on a signal pad into my hands. I recall Captain Irvine admonishing the young signalman “Young man, you don’t come uninvited into the Wardroom; take your hat off!” But my attention was elsewhere: I was reading the most chilling of messages, a signal one never wants to receive and one never to be forgotten.

The hand scrawled message was timed at approximately 2105 and simply read:

From MELBOURNE To FOCAF

Have come into collision with VOYAGER. Am rescuing survivors. Sea calm. Ends

My immediate reaction was to get confirmation the hand scrawled signal was correct, that it was not preceded by a qualifying “For exercise only” and was not some prank. “No sir” was the young sailor’s response. “It is as received and has been repeated to confirm”. With that I excused the signalman to enable him to return to the ship’s COMCEN. Captain Irvine enquired of me “What is MELBOURNE doing tonight?” to which I replied in great haste “She is night flying off JB with VOYAGER acting as RESDES”. To which CSO (A) replied “you must get COS onboard now”.

On bended knee in the captain’s harbour cabin, I unscrambled the safe combination as quickly as I could despite my shaking hands and obtained the phone number of the restaurant. The phone rang repeatedly, eventually answered by reception at “Prunier’s”, then one of Sydney’s finest restaurants. The conversation went along these lines. “Please get me the Maître D.” “You are speaking to the Maître D.” “Then may I speak urgently with one of your guests?” A gruff, husky voice HD enquired “What is the problem Ingram?” “Sir, I’m terribly sorry but I need you back onboard immediately”.

HD was naturally upset as his meal had just been served.

It is important to note all I knew at this stage was the ships had collided; no knowledge of the fact VOYAGER had been cut in two and, by now, the forward section was plummeting to a watery grave entombing scores of men.

While awaiting COS’s arrival at the after gangway I spoke by phone with my counterpart, a lieutenant commander in the FOICEAA command. Yes, he was aware of the collision as his COMCEN at KUTTABUL had received messages from the MELBOURNE requesting NOIC- JB and HMAS ALBATROSS assistance with helicopters and small craft. As the MELBOURNE had an ASW Gannet aircraft airborne at the time of the collision with Lieutenant “Toz” Dadswell at the controls, he would need to divert to the Naval Air Station at Nowra. The Area Command’s staff officer also advised his Chief of Staff, Captain Hinchcliffe, was at FOICEAA’s headquarters already and had taken charge of the recovery operation. I sensed something was amiss and noted the terse tone of the brief conversation.

“HD” alighted from a taxi and ran up the gangway; we adjourned a discreet distance out of earshot of duty sailors. I showed him the message to which he replied “Organise five land lines in my (harbour) cabin along with a flask of coffee. Recall FOO but disguise what you tell him. I want no-one to know what has happened. Do I make myself clear?! When you’ve done that phone Admiral Becher, but only after I tell you what to say”.

In 1964 there were no “secure” phone lines at Garden Island (GI) and that calls to/from ships alongside or moored were all made via the GI manual telephone exchange. Only authorised personnel could make trunk/STD calls and these had to be booked via duty civilian personnel manning the exchange. It was a laborious, time-consuming affair. Once connected the ladies at the exchange could eavesdrop on any call should they so wish. I’m not suggesting they did but one had to be very conscious of the fact no conversation, whether official or private on any subject matter, was secure. It was common and accepted practice that they remained in contact until both caller and receiver connected.

When I phoned FOO at his St Ives home, I was very conscious of the strict security quarantine imposed by COS. All I was able to say to Commander Doyle was that he was “required onboard by COS to assist an urgent situation”. Clearly FOO got the message; later confessing he’d broken the speed limit coming down the Pacific Highway and crossing the Harbour Bridge, adding that for once, he wanted to attract the police and for them to provide safe escort to Garden Island.

Once I’d organised the five phones for COS (a difficult task in a carrier where distances are great and phone points few) he directed me to contact the Fleet Commander, then in Canberra for a meeting with the Chief of Naval Staff. Locating RADM Becher that evening was not a simple task as I knew not his accommodation arrangements. I tried the usual hotels (of which there were few in Canberra in 1964) without success. The lady at the GI telephone exchange was also trying hard to locate the Fleet Commander.

I suggested we try the Duty Officer in Navy Office but his number rang out. Eventually a Steward answered the phone and had the Duty Officer phone me back. Yes, he knew where Rear Admiral Becher was; dining with Vice Admiral and Mrs Harrington at home and I should contact him there. Moments later Vice Admiral Harrington picked up the phone. “My name is Ingram, sir. I need to speak with Admiral Becher urgently”. “I’ll get him for you”. With that the Fleet Commander responded, but not until I heard a separate conversation. “Adelaide Advertiser here, who am I talking to? Hullo. Hullo, can you hear me?”

“Sir, please understand I’m directed to say very little; there’s been a collision involving your Flagship and your presence is required”. With that Admiral Becher responded “I understand. I’ll get my driver to take me to ALBATROSS. Have a helo readied to fly me to the MELBOURNE. I will travel via Moss Vale and call at the police station. If you’ve any further information I’ll phone from there”. I was impressed he was able to interpret my cryptic message. He knew his Flagship was night flying and the inherent risks involved in operating at close quarters with a rescue destroyer.

It would be a long and troubled drive fearing the consequences for all involved. I also knew that in 1964 the Navy didn’t have the technology to safely operate helos at night. But in an emergency, anything is possible, especially if the Fleet Commander is involved.

(As a postscript the Adelaide Advertiser was the first of the print media to obtain a hint of the story and throughout the first night made repeated calls to the SYDNEY to solicit further particulars.)

My role had changed from the moment COS repaired onboard when he rightfully assumed control. Having been relieved of my duty officer responsibilities I took on that of administration, essentially that pertaining to personnel. Later that evening my fellow staff officer, Graham Lynch (with whom I shared a cabin), returned onboard and we began the task of compiling names of victims, the injured and survivors. We also developed a plan to assist in managing media enquiries which we knew would increase as the long night began to dawn. In 1964 the RAN had no “media savvy” personnel, not even a PR department. We did know how to present the facts openly and accurately. If we didn’t know the answer we said so; “spin” was not in our lexicon.

It was a terrible shock when we learnt the forward half of VOYAGER had sunk; we knew most officers and many men would’ve been trapped therein. Our attention turned to the after section and a glimmer of hope it could be towed into Jervis Bay and lives saved. Some brave soul had been able to start, or restart, an alternator which provided power for pumps and lighting but, sadly, these efforts came to nought.

The signal to FOCAF from MELBOURNE simply read “After section of VOYAGER sank in position …….at…..”. We knew then the recovery operation was limited to searching for any survivors adrift on the black surface of the sea or possible bodies. By midnight we had the assurance from the MELBOURNE all possible had been done, several minor war vessels would remain in the area searching for men, bodies or wreckage. MELBOURNE was then directed to sail for Sydney at best possible speed.

I recall “HD” coming into our small compartment, the Admiral’s Office, several times during that night to view the Survivor, Casualty and Missing lists Graham and I were compiling as details were received by signal from the MELBOURNE. In return we briefed him and other senior staff officers on matters such as media enquiries which, as the night progressed, became more frequent. He insisted Mrs Stevens was to be the first next of kin to be informed and that he’d be leaving the ship at 0500 to call on her. He knew it would be only a matter of time before the media would attend her residence and he wished her to be fully informed of the terrible circumstances. While we couldn’t be absolutely certain Captain Stevens had been lost, “HD” didn’t wish to offer false hope. Again, it was a measure of the man that he made that visit.

While Graham Lynch was Section Officer (Personnel) he couldn’t be in two places concurrently. At dawn he drove to the RAN Hospital at Balmoral to await the arrival of injured survivors arriving by helicopter from the MELBOURNE and NAS Nowra. Here Graham was to get written “survivor statements”. I volunteered to meet MELBOURNE on her arrival at dawn on 12 February and get similar statements from non-injured survivors before they were sent on 10 days “Survivors’ Leave”.

I didn’t know what to expect when I stepped off the SYDNEY at the Cruiser wharf to await the flagship’s arrival. When that grey hull emerged from the morning mist with her attending tugs, I gasped in awe at the damage which became increasingly ugly as MELBOURNE was nudged alongside. Strange as it may seem nowadays but very few were present wharf side apart from those attending shore lines.

I didn’t know what to expect when I stepped off the SYDNEY at the Cruiser wharf to await the flagship’s arrival. When that grey hull emerged from the morning mist with her attending tugs, I gasped in awe at the damage which became increasingly ugly as MELBOURNE was nudged alongside. Strange as it may seem nowadays but very few were present wharf side apart from those attending shore lines.

Naval ambulances transported the walking wounded and those on stretchers to the RAN Hospital HMAS PENGUIN where Graham Lynch interviewed those in a more serious state. I went to “C” hangar in the MELBOURNE where VOYAGER survivors were mustered. Several things stand out in my mind to this day. Despite the horrors of the loss of their ship these men were chatting and behaving in a near normal manner. Their primary concern to me was “please hurry up so we can go on leave”.

Each man was issued with a sheet of paper and invited to write his account of where he was at the time of the collision, what he was doing, how did he escape, who was with him on board and in the water, how was he recovered and suchlike. To me it was like asking schoolchildren to write a simple essay and I was the teacher trying, in an amateurish way, to identify points which might help in piecing together an account for future reference. I had absolutely no idea these pieces of paper would be pored over by an army of lawyers and so forth in two Royal Commissions. Nor had I ever been subjected to the techniques needed to interview personnel who’ve been subjected to such trauma. A typical “statement” read along these lines:

“My name is Leading Seaman (Cook) Tony SMITH R12345. At the time of the collision, I was the duty Leading Hand in the main galley. After securing the galley I went aft to the waist to observe night flying operations before turning in. VOYAGER had been manoeuvring and it had taken longer than usual to serve the evening meal and clean-up for rounds. All of a sudden, I saw MELBOURNE appear out of the dark. She was much larger and closer and I thought we’ll collide. I ran towards the stern but didn’t make it before we were hit. As VOYAGER rolled over, I was flung into the sea where I observed sparks and flashes and heard the grinding of steel. MELBOURNE took ages to pass by. I kicked off my boots and swam to where I could hear voices of men calling out. I was in the water for 15-20 minutes before a cutter from MELBOURNE recovered me. There were other men with me in the water.”

Some survivors at first believed the ship had suffered a boiler explosion, others that one of MELBOURNE’s aircraft had flown into VOYAGER and blown up. There was general disbelief a collision had occurred. Before leaving the MELBOURNE, some insisted on inspecting the mangled bow while others simply couldn’t bring themselves to be inquisitive.

In colonial times States operated their navies for coastal and port protection on a regional basis, complemented by ships of the Royal Navy assuming overall protection of the fledgling nation’s sea lanes. Following the formation of the RAN as a unified force 1911-14, these regional divisions were maintained; hence NOICs (Naval Officer in Charge) for a state such as NOIC QLD, VIC, WA etc. The overall umbrella for operational ships was the responsibility of the Fleet Commander (known as FOCAF or Flag Officer Commanding HM Australian Fleet) while most shore establishments and minor war vessels reported to Navy Office via FOICEAA (Flag Officer in Charge, East Australia Area). Like any good rule there were exceptions including the CST (Commodore Superintendent of Training), HMAS CERBERUS.

While this arrangement had operated for 50 years, including two World Wars, it failed the Navy at a critical time in February 1964 when the VOYAGER was lost in the most tragic of circumstances. And here I highlight some of the serious defects based on my personal experiences. It’s possible these system faults were the reason I wasn’t called at either Royal Commission. Had I appeared, my evidence, especially under close examination by defence counsel, could’ve reflected poorly on Navy hierarchal structure and management. I cite some examples which confronted me that fateful night.

- As I described earlier, MELBOURNE and VOYAGER were “working up” in the Exercise Area east of Jervis Bay. Both “came under” FOCAF meaning they reported directly to the Fleet Commander. The area in which they were operating was the responsibility of NOIC JB (Jervis Bay) who reported to FOICEAA. Likewise, the SAR (Search and Rescue) craft based at the Marine Section, CRESWELL came under NOIC JB. The aircraft squadrons involved had yet to embark in the MELBOURNE hence were operating from the Naval Air Station at Nowra which reported to FOICEAA. And finally, the Boom defence vessel KIMBLA was in the exercise area towing a battle practice target back to Sydney following live firing gunnery exercises with VOYAGER. Now this is where the situation became confused and delayed.

- Immediately following the collision, MELBOURNE had signalled FOCAF “Have come intocollision with VOYAGER: Am rescuing survivors: sea calm”. The “Copy to” addressee was FOICEAA. As FOCAF’s Duty Staff Officer I had the responsibility of initiating recovery action until such time relieved by the Fleet Commander, his Chief of Staff or the Fleet Operations Officer. I’d made urgent contact with all three. Yet within minutes I’d been over-ruled by FOICEAA’s Chief of Staff who’d advised by phone from his HQ at Potts Point that “FOICEAA had assumed responsibility for the recovery operation”. I reported this matter to Captain Stevenson immediately upon his recall to the SYDNEY. There was, allegedly, a heated phone exchange between the two Chiefs of Staff resulting in FOCAF resuming charge of recovery, thereby vindicating my position. I was not privy to this phone conversation.

- In the meantime, confusion had arisen and valuable time lost. For example, KIMBLA had been directed by FOICEAA to slip the tow and cast the Battle Practice Target (BPT) adrift. She was instructed to head south at best possible speed to assist in the search for survivors. Then she was advised by FOCAF she was not required. KIMBLA then had to relocate the BPT and resume the tow to Sydney.

- While the two CRESWELL based Search and Rescue craft had sailed for the collision location within minutes of the signal being intercepted, I had no authority to direct them to do so as their commanding officers reported to NOIC Jervis Bay who, in turn, came under FOICEAA.

- Likewise, NAS Nowra had intercepted the signal advising FOCAF of the collision but that command and her helicopters came under the control of FOICEA, ALBATROSS being a land base. In 1964 none of the helos was equipped with an approved system for personnel recovery at night over water.

- The assistance from area commanders responsible for fleet support and associated assets had to be “requested” by FOCAF, all of which involved precious time.

Subsequent changes emanating from this tragic event would make the Navy response to a major emergency faster and simpler.