By Angus Britts

Wednesday 8 April 1942 was a day of ignominy for the greatest naval power the modern world had thus far known. Since 30 March the Royal Navy’s Eastern Fleet under the command of Admiral Sir James Somerville had been conducting a fruitless search to the south of Ceylon for a Japanese force of largely unknown composition. On 5 April, Easter Sunday, events to the north of the British fleet provided an alarming revelation for Somerville and his superiors in London. An early morning blitz against the anchorage and naval base at Colombo by a large formation of Japanese bombers with heavy fighter escort, and the subsequent destruction of two heavy cruisers by dive-bombers to the southwest of Ceylon that afternoon, confirmed the presence of a formidable Japanese carrier group. Having arrived at the isolated base at Addu Atoll on 8 April to replenish his low endurance ships, both Somerville and the British Admiralty separately concluded that the Eastern Fleet must be withdrawn from the vicinity in order to prevent its wholesale annihilation. For the first time since Nelson’s victory at Trafalgar in October 1805, a Royal Navy battlefleet had been compelled to recoil from the prospect of a major engagement against an enemy fleet of comparable size. This April marks the eightieth anniversary of the moment in history when Britannia’s lengthy mastery of the waves was emphatically rebuffed and thereafter superseded by the supremacy of the air weapon at sea.

From the outset of hostilities between Japan and the Western Allies on 7-8 December 1941 the Imperial Japanese Navy had contemptuously brushed aside all naval efforts on the part of its opponents to stem Japan’s Far-Eastern aero-amphibious offensive that intended to conquer what Tokyo’s strategists referred to as the ‘Southern Resources Area’. Stretching along the length of the Malay Barrier and incorporating the vastness of the Indonesian archipelago, this region contained the vital natural resources – most particularly oil – that were required to sustain the Japanese war economy. In four months of fighting, Japan’s mastery of naval-air warfare had repeatedly stunned her enemies. Carrier-borne airpower reaped rich pickings at Pearl Harbor, Darwin, and Tjilatjap, land-based naval aircraft sank the British capital ships Prince of Wales and Repulse in the South China Sea, and the skilful use of floatplane reconnaissance paved the way for victory at the battle of the Java Sea. With the Southern Resources Area now firmly under new management, two tasks remained for the Imperial Navy before it turned its focus to the Pacific, and the anticipated final defeat of the U.S. Pacific Fleet. In order to secure the left flank of the Imperial Japanese Army’s invasion of Burma, all Allied naval activity needed to be paralysed in the Bay of Bengal. And with a fresh British fleet known to be assembling at Colombo, another surprise attack by Japan’s carriers presented the best opportunity to neutralise the Royal Navy’s presence in the vast expanse of the Eastern Indian Ocean.

To execute what became designated as Operation C, two fleets were assembled in late March 1942. Under the command of Vice-Admiral Ozawa Jisaburo, the Second Expeditionary Fleet was to depart the Andaman Islands on 1 April and steam into the Bay of Bengal. Equipped with the light carrier Ryujo, five heavy cruisers, one light cruiser, four destroyers, and five submarines, Ozawa’s force would seek to sink every merchant ship which had the misfortune to draw his gaze. Based at Staring Bay in the Celebes, the First Air Fleet commanded by Vice-Admiral Nagumo Chuichi departed its anchorage on 26 March on-route to a position south of Ceylon from where the airstrike targeting Colombo would depart the decks of its carriers. Five of Japan’s big carriers, Akagi, Shokaku, Zuikaku, Soryu, and Hiryu, were present, along with four fast battleships, two heavy cruisers, a light cruiser, and eleven destroyers. Between them the Japanese carriers deployed some 330 combat aircraft and sixty reserves, while Ozawa’s Ryujo accommodated forty-eight planes. Whereas Nagumo sought another Pearl Harbor-style triumph, Ozawa’s utilisation of carrier aircraft, surface warships, submarines, and long-range flying boats, represented a most potent combination of arms for commerce-raiding activities.

The British naval response to the initial Japanese onslaught progressed in rough accordance with plans which had been hotly debated by Winston Churchill and the Admiralty since August 1941. Though a general consensus was reached on assigning convoy protection in the Indian Ocean as the highest priority, Churchill also pushed for the initial despatch of a deterrent force to Singapore. It was eventually agreed that Force Z (Prince of Wales, Repulse, Indomitable) would proceed to Singapore, with a larger force of capital-ships and carriers to be assembled at Colombo by April 1942. As events transpired, the carrier Indomitable sustained damage in the Caribbean as she left for Singapore in November 1941. Misfortune elsewhere shaped the final composition of the Eastern Fleet. The loss of both the battleship Barham and the carrier Ark Royal to U-Boat attack in the Western Mediterranean that same month, and the subsequent crippling of the battleships Queen Elizabeth and Valiant by Italian naval special forces at Alexandria in December, limited the available big ship options. So it was that in late March 1942, Somerville’s nascent command contained a mixture of the good, the bad, and the decidedly ugly. To create the most efficient fighting formation possible, he formed the best ships into Force A, and the remainder into Force B. Force A consisted of the modern carriers Indomitable and Formidable, the refurbished battleship Warspite, two heavy and two light cruisers, and six destroyers. Force B under Vice-Admiral Sir Algernon Willis contained the old light carrier Hermes, four unmodernised ‘R’-class battleships (Ramillies, Royal Sovereign, Revenge, and Resolution), three light cruisers, and eight destroyers.

In this instance the British commanders possessed one key advantage which had been missing at Pearl Harbor – the knew that the Japanese were coming. The assembly of the Eastern Fleet at Colombo assumed greater urgency when London learned through intercepts by the Ultra codebreakers that enemy naval operations in the Indian Ocean were expected in early April. Just what the Japanese fleet was up to remained a mystery, yet the Admiralty’s strategists and Churchill thought they had the answer. In their deliberations it was concluded that a raiding operation by a small number of surface ships, namely battleships and cruisers, with possible support from a single aircraft carrier, would be the most likely threat. The final composition of Ozawa’s command matched this line of reasoning. But at no time, as borne out by the relevant correspondence between Churchill and the Admiralty over the issue, did either party contemplate the involvement of a large enemy carrier formation. As the naval historian Russell Grenfell later explained, Churchill in particular was convinced that a Bismarck-style sortie would be attempted:

The major error into which he [Churchill] seems to have fallen is indicated by his obvious obsession, noticeable in most of his minutes, memoranda, and telegrams during this period, with the idea of raids by individual ships and not engagements between squadrons. He thought in terms of the Japanese raiding the British communications in the Indian Ocean and of the British Far Eastern ships raiding the Japanese communications somewhere else, though he did not say where. He clearly failed to realise that the main issue at stake was an organised struggle for the command of the sea. What we should and did have to face in the south-west Pacific were not the sorties of so many Japanese Bismarcks but the embattled challenge of a superior Japanese fleet.

The sinking of the Bismarck in May 1941 and prior defeat of the Italian fleet at Cape Matapan in March of the same year were a triumph for the Royal Navy’s skilful use of combined-arms operations. In each instance the torpedo planes carried by the British carriers were deployed to slow down the faster enemy ships, and thus bring them within gunnery range of the accompanying capital ships. With the addition of radar, these tactics proved deadly efficient against the carrier-less European Axis navies. Such thinking had prevailed within the British, American, and Japanese navies throughout the 1930s, with all three committed to a belief in the supremacy of the battleship at sea. Even given the massive strides that had taken place within naval aviation in the same period, the aeroplane remained subordinate to the needs of the big guns. In April 1941 the Japanese broke ranks, largely due to the influence of Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku, the commander of the IJN’s Combined Fleet. Stemming from his days as head of the navy’s aviation technical branch in the early 1930s, Yamamoto became a firm proponent for aviation taking the leading role at sea. His support of the plan to attack Pearl Harbor with multiple carriers led to the creation of the First Air Fleet as the IJN’s operational spearhead. Within this force, the accompanying battleships and cruisers were to operate first and foremost as escorts for the carriers. Victory over the enemy was to be achieved by the combination of stealth, surprise, and overwhelming aerial firepower.

In terms of combat capabilities, the advantages enjoyed by Nagumo’s fleet in particular were ominous. All of the available Japanese carrier-borne aircraft were of modern design; the superlative Mitsubishi Type 0 (‘Zeke’) fighter having consistently terrorised its opponents in the fighting thus-far. Both the Aichi ‘Val’ dive-bomber and the Nakajima ‘Kate’ attack plane were proven performers, with all three types crewed by elite aviators. By comparison, the air assets available to the Fleet Air Arm aboard the two large British carriers were wholly inadequate. Between them the Formidable and Indomitable could fly off a total of forty-five Albacore torpedo-bombers and just over thirty fighters, none of which, save twelve Grumman Martlets (the export version of the American F-4 Wildcat), were capable of mixing it with the Zekes. Within Force B the Hermes carried a squadron of twelve Swordfish torpedo-bombers. Though both the Swordfish and Albacore biplanes were excellent strike aircraft, they could not hope to survive long in airspace dominated by enemy fighters, and the lack of British fighters made it almost impossible to provide an effective escort without denuding the Eastern Fleet’s need for a defensive combat air patrol. Likewise limiting the capabilities of Admiral Somerville’s command was the condition of his fleet’s battleships and many of its screening vessels. Both the four ‘R’-class ships and the majority of the light cruisers were not suited to long-range operations as their fuel tankage and fresh water supplies required continual topping-up. Nor did these ships, and a number of others, possess adequate anti-aircraft (AA) defences, while the ‘R’s could barely make 20 knots, thereby drastically reducing the mobility of Force B in the conduct of any joint operations with Force A.

With a considerable portion of the British capital ships so poorly suited to a modern combat environment, both Somerville and the Admiralty were of the view that the Eastern Fleet’s most effective role was that of a deterrent – a so-called ‘fleet in being’. The fleet commander subsequently described his instructions from London in the following terms. “First and foremost, the total defence of the Indian Ocean and its vital lines of communication depended upon the Eastern Fleet. The longer this fleet remains ‘a fleet in being’, the longer it will limit and check the enemy’s advances against Ceylon and further west. This major policy of retaining a fleet in being, already approved by their Lordships, was, in my opinion paramount.” The Japanese, however, were seemingly unwilling to be dissuaded by deterrents as demonstrated by the fate of the Prince of Wales and Repulse four months earlier. So it was that on 30 March the Eastern Fleet departed Colombo and steamed to the south as Somerville devised a plan to intercept the expected arrival of the enemy force in the area:

The enemy could approach Ceylon from the north-east, from the east, or from the south-east, to a position equidistant 200 miles from Colombo and Trincomalee. This would enable the enemy to fly off aircraft between 0200 and 0400 and, after carrying out bombing attacks on Colombo and Trincomalee, allow the aircraft to return and fly on after the first light (about 0530); forces could then withdraw at high speed to the eastward. I was assuming that the Japanese carrier-borne bombers could have approximately the performance of our Albacores.

My plan was therefore to concentrate the Battlefleet, carriers and all available cruisers and destroyers and to rendezvous . . . in a position from which the fast division [Force A] could intercept the enemy . . . and deliver a night air attack. The remainder [Force B] to form a separate force and to manoeuvre so as to be approximately 20 miles to the westward of Force A. If Force A intercepted a superior force, I intended to withdraw towards Force B.

On the supposition that the enemy adopted what I considered to be his most probable plan, it was certain that he would have air reconnaissance out ahead. . . . The success of my plan depended on my force not being sighted by enemy air reconnaissance.

Against a German or Italian opponent, Somerville’s plan had considerable merit. Such an interception was favoured by the possession of radar, and the prior experience of night aerial attacks which had delivered the British a resounding success against the Italian fleet at Taranto in November 1940. Yet it suffered from one potentially catastrophic flaw, namely that the composition of the enemy fleet remained unknown. If it were a raiding force in the mould anticipated by London, the prospects for victory were reasonable. Otherwise, the Eastern Fleet would find itself in dire trouble if Japanese reconnaissance aircraft flying from a substantial carrier force found the British first. Likewise, Somerville had not been appraised of the performance of the Japanese fighters and strike aircraft, particularly in terms of their combat range. Had he been so, it is highly likely that no such flanking attack would have been contemplated. Additionally, the Eastern Fleet had enjoyed only a very limited period of familiarisation in operating as a fleet unit, while the carrier air groups aboard Formidable and Indomitable were largely inexperienced; the Hermes being unable to operate with Force A due to her low speed and lack of endurance.

As events transpired the Japanese failed to trip the snare on the night of 31 March, leaving Somerville with no alternative than to retire to Addu Atoll (of which the Japanese had no knowledge) for refuelling. Land-based reconnaissance by Catalinas flying from Colombo detected no sign of an enemy fleet until late on the afternoon of 4 April. At 1630 hours that day the British commander learned that a Japanese force had been sighted 600 miles to the east/north-east of Addu Atoll, and some 360 miles to the south of Ceylon. With refuelling unable to be completed before the early hours of the following morning, Somerville decided to attempt an interception 250 miles south of Ceylon on the morning of 6 April – the earliest moment that both British formations would be in a position to do so. Instructions were also sent to Colombo for the heavy cruisers Cornwall and Dorsetshire to re-join Force A, both ships having remained in port when the fleet originally departed. Still, however, Somerville had no knowledge of what exactly he was facing, as the Catalina which spotted the enemy had been shot down before a confirmatory message could be transmitted.

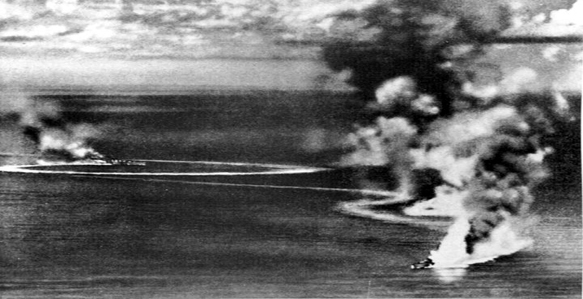

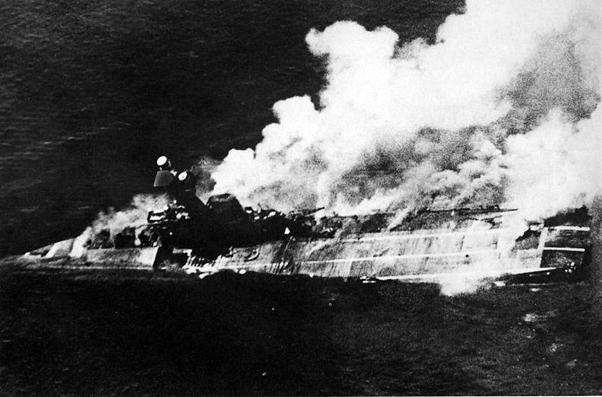

Oblivious to the activities of his opponents, Vice Admiral Nagumo positioned the First Air Fleet less than 200 miles south of Ceylon in readiness for the planned airstrike against Colombo at dawn on 5 April. At 0625 hours that morning the first of seventy-five bombers and fifty Zeke escorts arrived above the Colombo roadstead. Thanks to the raid being detected on radar, the Japanese airmen for once found themselves opposed by reasonably strong fighter opposition in the form of thirty RAF Hurricanes and six FAA Fulmars. With the roadstead virtually empty of shipping, the attacking bombers sank the destroyer Tenedos and damaged several fleet support vessels; dockyard facilities and an oil farm were also targeted. Nineteen British fighters (and six Swordfish from Hermes also intercepted by the Zekes) were downed, while Japanese losses amounted to six Vals and a single Zeke. There was better news for Nagumo’s flyers several hours later when aerial reconnaissance located the Cornwall and Dorsetshire some 250 miles to the southwest of Ceylon. Approximately eighty Vals without fighter escort were flown off to intercept. At 1344 hours the airstrike was picked up on Indomitable’s radar less than ninety miles from Force A. Sixteen minutes later the Vals found their targets. In just fifteen minutes both cruisers were sent to the bottom by a hail of bombs: post-war analysis concluding that approximately 90% accuracy was achieved by the attackers. Subsequent rescue operations by the Royal Navy resulted in over 1,120 officers and men from both ships’ crews being saved.

Thereafter the First Air Fleet proceeded first to the northwest, and then to the southeast, as the Eastern Fleet continued to mount a localised search. Further reports in the evening of 5 April placed the Japanese fleet to the east-northeast some 120 miles distant. These signals also indicated the presence of at least two carriers and several battleships. When another signal from Colombo indicated that the enemy had changed course and was heading southwest towards Addu Atoll, Somerville sought to place Force A into position to fight a supporting action with Force B (on route from Addu after refuelling) on the following morning. Unbeknown to the British, by this point Nagumo had commenced retracing his tracks. Once again denied, Somerville proceeded towards Addu, but chose to delay the Eastern Fleet’s arrival there as latest reconnaissance information still placed the Japanese fleet somewhere between Colombo and the atoll base. The sighting of two Japanese submarines in the vicinity of the latter, and the British commander’s desire to stay away from Addu and thereby avoid a potential repetition of Pearl Harbour, meant that his fleet did not arrive for refuelling until 1100 hours on the morning of 8 April, by which time the enemy had again vanished from sight.

Now presented with the opportunity to interpret all the evidence regarding the true identity of the Japanese fleet, Somerville and the Admiralty took the only logical course of action available – to retire the Eastern Fleet from the area as quickly as possible. Force B was to proceed to the Kenyan port of Kilindini, while Force A steamed for Bombay. Both formations left Addu early the following morning (9 April), however several ships assigned to Force B, namely the Hermes, two small escorts and several fleet auxiliaries, remained detached in the vicinity of Ceylon. As the Eastern Fleet was beginning its withdrawal away to the south, the First Air Fleet emerged near the naval base at Trincomalee on the north-eastern coast of the island. Detected again by radar, a Japanese airstrike inflicted minimal damage in a dawn attack against the base and the nearby RAF aerodrome at China Bay. More resistance was forthcoming in the air, with four Japanese and eleven British aircraft being shot down. By way of retaliation, nine RAF Blenheim bombers located the Japanese ships and unsuccessfully attacked the giant carrier Akagi, Nagumo’s flagship. But in a repeat of the circumstances on 5 April, the sighting of the Force B stragglers to the south of Ceylon gifted the Japanese another easy target. A strike comprised of eighty Vals found the enemy vessels at 0700 hours and took thirty minutes to sink the Hermes, the escorting destroyer HMAS Vampire, the sloop Hollyhock, and two oilers. With these final attacks completed, Nagumo’s ships steamed for Singapore, and a subsequent triumphal return to Japanese home waters.

Away to the north in the Bay of Bengal, Vice-Admiral Ozawa’s Second Expeditionary Force was wreaking havoc upon the defenceless Allied merchant shipping located there. Departing his forward base at the Andaman Islands on 1 April, Ozawa had divided his force into three surface groups (Northern, Southern, and Central) and issued orders for them to sweep the area as far west as the eastern coastline of India. Over the next six days a total of twenty-nine Allied steamers (approximately 150,000 tonnage) were sunk by the three formations.

On 6 April aircraft from the Ryujo bombed targets at Vizagapatam and Cocanada, spreading panic amongst the civilian population along the Indian coast. In the course of its mission the Second Expeditionary Fleet did not encounter any air or naval opposition, and several drastic outcomes were forthcoming. For at least the next two months all British merchant traffic lay paralysed, and the vital port of Chittagong rendered useless as a result. This absence of shipping played a not inconsiderable part in generating a subsequent famine within modern Bangladesh which claimed an estimated 100,000 lives. Ozawa’s mission provided compelling support for future combined-arms commerce-raiding operations, however this proved to be the final sortie of its kind executed by the Imperial Japanese Navy.

The eastward departure of the Japanese fleets marked the final occasion upon which the IJN would mount any large-scale operations to the west of the Philippines. Ahead lay the gruelling slog of naval conflict in the Pacific, and ultimate defeat for Japan against the American aero-amphibious machine. When the Royal Navy returned to the Indian Ocean in strength during 1944, the war at sea had already been decided. Thereafter, what became known as the British Pacific Fleet participated in the invasion of Okinawa as a component of the United States Third/Fifth Fleet. For a navy which had prevailed in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean after a long and bloody fight, this public demotion of its former standing would have been a bitter pill to swallow. Indeed, it was only through strenuous representations from Churchill to Roosevelt that enabled the RN to be present at all. If any belief still persisted within the British political and military establishments that their nation remained an equal partner with the United States, the sight of the British Pacific Fleet dwarfed by the vast assembly of American naval power revealed otherwise.

Operation C became the first and only occasion in the Second World War where a fleet-scale confrontation between the British and Japanese navies was at least partly realised. In the published post-war histories, the events of 4-9 April 1942 have never been afforded the same prominence as the destruction of Force Z and the later carrier battles in the Pacific. Yet the battle’s significance in the broader narrative of naval studies is unmistakeable in several key respects, as alluded to within Winston Churchill’s post-war commentaries:

The experiences of the last few days [in the Indian Ocean] had left no doubt in anyone’s mind that for the time being Admiral Somerville did not have the strength to fight a general action. Japanese successes in naval air warfare were formidable. In the Gulf of Siam two of our first-class capital ships had been sunk in a few minutes by torpedo aircraft [referring to the loss of the battleship Prince of Wales and the battle cruiser Repulse off Kuantan, Malaya, on 10 December 1941]. Now two important cruisers had also perished by a totally different method of air attack–the dive-bomber. Nothing like this has been seen in the Mediterranean in all our conflicts with the German and Italian Air Forces. For the Eastern Fleet to remain near Ceylon would be courting a major disaster.

Churchill’s summation reflected the reality of the Royal Navy’s weakness when faced with a carrier-equipped opponent. Though the British and Commonwealth naval forces had been exposed to a hammering in the European theatres from Germany’s infamous land-based Stuka dive-bombers, no such threat was forthcoming from the sea, and the Royal Navy’s combined-arms approach could be pursued with justified confidence of achieving success. Yet when pitted against Japan’s embrace of the massed carrier airstrike as the principal means of attack, the British tactics were extremely hazardous, if not downright suicidal, especially when the mobility of the Eastern Fleet in this instance was badly compromised by its waddling battleships. But even in the absence of slow obsolete vessels like the ‘R’s and the Hermes, no contemporary British fleet could match the aerial prowess of the First Air Fleet, especially when it came to adequate numbers of high-performance fighters, and the utilisation of specialised dive-bombers. In December 1941 the last of the few Blackburn Skua dive-bombers possessed by the Fleet Air Arm were withdrawn from shipboard service, leaving the RN’s four big Illustrious-class carriers (including the Formidable and Indomitable) dependent upon their Albacore and Swordfish torpedo-bombers attacking with bombs instead. By mid-1943 this situation was well on its way to being remedied through the acquisition of much improved aircraft (particularly those of American origin), and with these upgrades came an acceptance from the Admiralty that aircraft-carriers deployed in strength were the new centrepiece of fleet operations.

Churchill’s words also shone light on other deeper truths, namely the assortment of prior events and circumstances which dictated to both Admiral Somerville and the Admiralty that retirement from the Eastern Indian Ocean had been the only feasible option available to the Eastern Fleet. British adherence to the Washington and London naval arms-limitation accords in the 1920s and 1930s reduced the Royal Navy to a one-power ratio fleet. Heavy cuts to the Admiralty’s budgetary outlays resulting from the strained economic circumstances of the late 1920s and early 1930s seriously denuded Britain’s shipbuilding industries, which slowed eventual rearmament through the need to rehabilitate these facilities. With greatly reduced funding, the Admiralty itself erred by not prioritising sufficient resources for research and development, particularly in the field of naval aviation, while the operational evolution of the Fleet Arm was hamstrung for much of the interwar period by conservative gunnery-centric thinking within the RN’s senior command. Thus, when war with Germany commenced in September 1939, British sea power remained deficient in a number of key areas. The nature of the campaigns waged in the Atlantic and the Mediterranean permitted the Admiralty to successfully exploit the deficiencies of its opponents and mitigate many of its own drawbacks, albeit at a terrible cost in lives and ships. Against the Japanese, however, the full extent of British shortcomings in naval airpower especially could no longer be compensated for, thereby leaving the task of eventually defeating Japan at sea squarely in the hands of the United States Pacific Fleet.

Though the Eastern Fleet’s mission had been largely conceived as a trade protection measure, its presence in the Far East did provide some small level of comfort to the Australian government when the initial deployment of Force Z was conveyed to Canberra in late 1941. Throughout the post-war era, the Anglo-Australian wartime defence relationship has been a source of frequent controversy within Australian historical circles and the wider public forum, spurred on by the disastrous outcome of the so-called ‘Singapore Strategy’, Australia’s supposed pre-war guarantee of continental naval security. One of the most frequent areas of discussion revolves around the failure of Whitehall to send a powerful battlefleet to the base at Singapore as it had pledged to do so since the inception of the strategy in 1923. Yet while the disaster that befell Force Z is a regular reference point, Operation C has been just as regularly been overlooked. As such, a comprehensive analysis cannot be articulated as the presence of Force Z was inextricably linked to the wider assembly of the Eastern Fleet that would follow. When both episodes are considered as a whole, the concept of a British fleet steaming to the successful rescue of a directly-threatened Australia in the period December 1941 – May 1942 is not sustainable, given the formidable disparity between British and Japanese operational capabilities then in existence.

In the decades following the Second World War the Royal Navy has fulfilled a critical role for NATO in partnership with the USN and other European navies, while the British fleet’s nuclear submarine arm became the new cornerstone of that nation’s strategic deterrent. Recent acquisitions of large carriers and other warships highlights a renewed push on Whitehall’s part to rejuvenate British surface naval power on a global basis. Initiatives such as the recently-negotiated AUKUS agreement have likewise facilitated this policy. It is to be hoped that this rejuvenation is never tested again in war, though the strained geopolitical situation which currently exists may determine otherwise. History should record that 4 – 9 April 1942 was the moment when the RN, staring into the abyss of an ignominious defeat without prior equal, was compelled to acknowledge airpower’s mastery at sea, and thereby set in train a lengthy and at times painful process to affirm its relevance as the modern fleet we see today.

Short Bibliography: Britts A: Neglected Skies: The Demise of British Naval Power in the Far East, 1922-42 (Naval Institute Press, MY 2017); Britts A: A Ceaseless Watch: Australia’s Third-Party Naval Defense, 1919-1942 (Naval Institute Press, MY 2021).