By Richard Broinowski AO.

Address to the Pioneers Club, Trafalgar Day Lunch on 26 October 2021, published in The Pioneer December 2021.

Richard Broinowski, AO, is an author and retired Australian diplomat. His first posting was to the Australian Embassy in Japan following the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games. After subsequent postings in Rangoon, Tehran and Manila, he became Australia’s Ambassador to Vietnam, then to the Republic of Korea, and finally to Mexico, with joint accreditation to the Central American Republics and Cuba. He took time out from diplomacy to be General Manager of Radio Australia in the early 1990s. On retirement, Richard was an adjunct professor of communications at the University of Canberra, then at Sydney University. He has authored six books and graciously supplied for publication this text of his address.

At first glance, the topic seems to be a flawed question. Heihachiro Tōgō was indeed a famous Japanese naval commander, but given the wide cultural and economic differences between Great Britain and Japan, why choose him to compare with Nelson? And if such cultural disparity is permitted, why not consider other Asian seamen of equal valour and ability, such as Isoroku Yamamoto, commander in chief of the Combined Japanese Imperial Fleet during World War 2? Or Korean Admiral Yi Sun-sin, whose statue bestrides Gwanghwamun Plaza in the centre of Seoul (another statue in Pusan). With his armoured turtle ships propelled by sail and oar, Yi defeated much larger Japanese invading naval forces during attempts by Toyotomi Hideoshi from 1592 to 1598 to conquer Korea during the Joseon Dynasty.

Part of the answer is Admiral Tōgō’s connection with the Royal Navy, which the other commanders did not have. He came to prominence during Japan’s rapid modernisation following the Meiji Revolution in 1868. Driven by Japan’s perceived vulnerability to an industrialised West, Emperor Meiji reversed sakoku, the isolationist policy of the Tokugawa Shogunate, and began a massive modernisation program to adopt the best technologies of the European powers in industry, education, transport, land reform, and the centralisation of government.

Above all, the leaders under Meiji urgently wanted to modernise Japan’s army and navy. They disarmed the samurai, introduced universal conscription for young men, obtained the world’s most advanced military and naval weapons, and brought foreign experts to instruct Japan’s soldiers and sailors in their use. And as Britain had the world’s most powerful navy, Japan sent its most promising sailors to learn Britain’s naval skills. One of them was Heihachiro Tōgō.

Tōgō was a wonderfully appropriate choice. Born in 1847 to a samurai family of the Satsuma clan in Kyushu, he retained early childhood memories of the arrival of Admiral Perry’s four fire-breathing black ships in Tokyo Bay in 1853 to force the Shogunate to open Japan to trade with the United States. In 1863, at the age of 16, he participated in the defence of the fort of Kagoshima when a British squadron under Admiral Augustus Kuper bombarded the town in reprisal for the samurai killing of Charles Richardson, a British merchant.

Three things were seared into Tōgō’s brain as a result of his youthful experiences: Japan was impotent without western technology; its primary defence against outside aggression must be a very strong navy; and it must learn the principles of self-defence.

In 1871, Tōgō embarked for England. As an ‘oriental’, he was not permitted to attend the Royal Navy college at Dartmouth, but was billeted on a hulk training ship, Worcester, where he studied European history, mathematics, and mechanical drawing. He visited the Australian colonies during a cruise on HMS Hampshire, and watched with interest the building of Fusō at Yokosuka, the first British- constructed warship for the new Imperial Japanese navy. Captain Smith, Tōgō’s British tutor is reported to have said of him: ’Tōgō is not what you would call brilliant, but a great plodder, slow to learn but very sure of what he has learnt’.

So where do comparisons between Nelson and Tōgō begin? Was Tōgō sufficiently distinguished to compare to Nelson?

Let us start with their naval careers. Through the influence of his uncle Maurice Suckling, a high-ranking naval officer, Nelson joined the Royal Navy in 1771 at the age of 12. As he matured, he was noted for his calmness, his physical courage, and his intelligent grasp of tactics. In 1779, the 20-year old gained his first command as post-captain of the frigate Hinchinbroke. He suffered periods of illness and unemployment at the end of the American War of independence, but returned to service at the outbreak of the First Revolutionary War against France in 1792. He lost an eye in the capture of Corsica in 1794, and an arm during a failed assault on the Spanish Canary Islands in 1797. A string of victories followed as Nelson rose through the ranks – notably in the Battle of the Nile against the French in 1798, and the First Battle of Copenhagen against the Danes in 1801.

Nelson’s greatest (and last) victory began with the Royal Navy’s blockade in 1805 of a French-Spanish fleet in Cadiz, a port on the south-west corner of Spain. The battle took place on 21 October off Cape Trafalgar between 33 allied ships and 27 British. The stakes were high. Napoleon had already abandoned his plan for his Grande Armée to invade Britain before Trafalgar, but if his fleet had beaten Nelson, he may well have revived it during a massive build-up of his navy which followed. On board his flagship Victory, a three tier, 104-gun, first-rate ship of the line, Nelson boldly divided his vessels into two columns and sailed them directly at the combined fleet, separating them into three groups which could be attacked individually. Twenty two Spanish and French ships were sunk. The British lost none.

Shot by a French sharp shooter during the closing stages of the conflict, Nelson died. His body was returned to Britain to great lamentation at his death, but even greater rejoicing at his victory. Admiral Villeneuve, commander of the combined fleet, was captured along with his flagship Bucentaure and attended Nelson’s funeral while on parole.

Tōgō’s career was equally illustrious and almost as consequential. The Sino- Japanese War, a dispute between the Qing Dynasty and Japan over influence in Korea, began in 1894. As captain of the British-built protected cruiser Naniwa, Tōgō participated in several naval engagements including the Battle of the Yalu River, the Battle of Port Arthur, and the Battle of Weihaiwei. He was in the thick of the Pescadores campaign and in the invasion of Taiwan. Like many of his compatriots, he was scandalised when the Triple Intervention of France, Germany and Russia pressured Emperor Meiji to overturn the onerous terms of the Treaty of Shimonoseki of 17 April 1895, and hand back the Liaodong Peninsula to China.

The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5 (Nichiro-Sensō) began over competing interests in Manchuria and Korea. Japan offered to withdraw any claim to Manchuria if Russia recognised Korea as being within Japan’s sphere of interest. Russia refused, asking Japan to recognise Russian influence on the Korean Peninsula north of the 39th parallel. A stalemate followed during which Japan launched a surprise attack on Russian forces in Port Arthur on the Liaodong Peninsula on 9 February, 1904. (They perfected the art of the surprise attack at Pearl Harbour 37 years later).

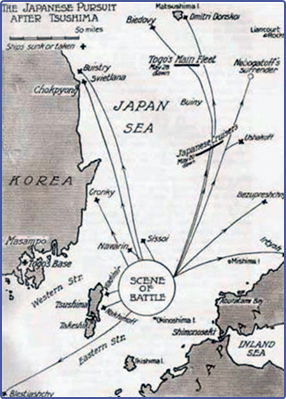

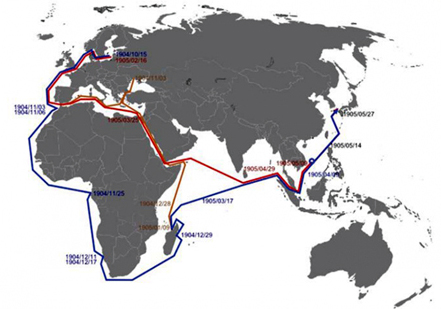

When the Tsar ordered his Baltic Fleet to embark on an extremely long voyage, some ships through the Suez Canal, others around the Horn of Africa, to attack the Japanese Imperial Fleet, his objectives were to relieve Russian ships bottled up in Port Arthur, and for the combined fleets to head for Vladivostok to re-group before deciding how to continue the war against Japan. This did not occur because the Japanese intercepted the Baltic Fleet between Korea and Japan, negating any capacity it might have had to relieve Port Arthur.

The battle of Tsushima Strait (Nihonkai-Kaisen) was the last and greatest two- dimensional confrontation between armoured steel battleships, and the first using wireless telegraphy. On paper, the fleets were approximately the same size. But the Japanese had a number of key advantages, which, with hindsight, made their victory all but inevitable.

The Japanese crews were fresh, well trained and eager for battle, whereas the Russians were not. Their ships were slowed by extensive fouling of their hulls after an eight-month sea voyage, and their crews were dispirited, unfit and lacking in training. Many of the Japanese ships, including Mikasa, Tōgō’s flagship, were highly- efficient British-made and tested pre-dreadnoughts. The Russians had a mixture of old ships verging on the obsolescent and new untested battleships of the Borodino class. Japanese guns were armed with high-explosive shells using shimose picric acid powder. The Russians were armed with less modern armour-piercing shells propelled by nitrocellulose (gun cotton). The Japanese fleet used centrally-controlled gun laying technology, the Russians allowed each of their ships to lay their guns individually. The Japanese used their own wireless telegraphy. The Russians had German telegraphy with which they were unfamiliar.

Above all, the Japanese were led by Admiral Heihachiro Tōgō, a man they admired, even worshipped; the Russians by Zinovy Rozhnestvensky a fiery- tempered Admiral and strict disciplinarian who belittled his crews. They knew that he was deeply pessimistic about his chances of success at Tsushima.

The two-day battle concluded on 28 May 1905. Of the Russian fleet of 38 ships, 19 were sunk, seven captured, and two scuttled. One escaped back to Madagascar, and only three reached Vladivostok – a cruiser and two destroyers. Of the Japanese fleet, three torpedo boats were sunk. A bitterly-negotiated peace treaty was signed the following September, thus ending the war. Its legacy lives on through unsettled Russo-Japanese claims to disputed islands in the Kuriles, and mutually-held suspicions about national motives that persist today.

The outcome of the battle caused astonishment in Europe that an oriental country could defeat a leading European naval power. It also demonstrated that ships with speed and long-range guns could defeat slower ships with shorter-range guns. This in turn led to a revolution in naval technology, when Britain’s First Sea Lord, Jackie Fisher, one year after Tsushima, urged the building of Dreadnought, a 21- knot battleship armed solely with high-calibre 12 inch guns, and driven by steam turbine engines. Its advent led to a pre-World War 1 naval arms race between Britain and Germany.

Can one usefully compare the skills of two admirals fighting naval battles with vastly different technologies? Nelson’s fleet consisted of cumbersome wind-driven wooden ships directed by signal flags, with tiered rows of fixed guns, each firing a cast-iron cannon ball weighing up to 32 pounds at a thousand feet per second – an ugly thing to receive. One hundred years later, Tōgō commanded armoured steel ships communicating with each other via telegraphy, driven by steam engines and propellers, firing high explosive shells from rotating turrets. Nelson had to make trickier decisions than Tōgō to get his ships into firing position, but the carnage, from wooden splinters raining on closely-packed gunners between decks on the one hand, and steel shards from high explosives hitting men in less concentrated positions on the other, would have been equally horrendous. Both Nelson and Tōgō had superb tactical sense and admirable calmness under fire.

Both men also had a similar capacity for the selective disregard for orders, or, put less politely, for insubordination. Nelson was an outstanding practitioner, both at the battles of Cape St Vincent in 1797 and Copenhagen in 1801. At Cape St Vincent, before any order was given for individual ship action, Nelson saw that the Spanish were about to escape, and taking his own initiative, wore his ship out of line and cut them off. At Copenhagen he deliberately disregarded Admiral Hyde Parker’s signal to break off heavy action, by putting his telescope to his blind eye so that he could truthfully say he had not seen it.

Tōgō came from a different culture, where gekokujo, disobedience to direct orders, became ‘rule from below,’ a respectable action if it could be proven to be for the good of the country. That’s why Caesar-like murder, for example, the pre- war assassination of Prime Minister Inukai and other politicians by young naval officers, was a respectable part of Japanese tradition if driven by patriotism and purity of motive. When asked about this and other political murders, the retired Admiral Tōgō gave a delphic but unhelpful response in 1932 – ‘All the officers of the imperial Navy must be prudent in speech and action.’ Hardly a condemnation.

How about their private lives? Here were profound differences. Nelson had a complex personality. He was talkative, a copious writer, vain, vivid of thought, with a strong desire to be noticed by his superiors and the public. He based the authority of his commands on love rather than authority. He inspired his crews with courage and charisma – the Nelson Touch. On the negative side, he was easily flattered by praise. He was dismayed if not given credit for his actions, and took risks to merit it. He was driven by insecurities. He suffered violent mood swings. He was vain and loved to receive decorations, of which there were many. His private life was a mess. He betrayed his wife, Frances ‘Fanny’ Nelson with a quite public, long-term relationship with Emma Hamilton, an English maid, model, dancer, actress, and the mistress of several men. She was denied attendance at Nelson’s funeral by the Establishment.

According to his many observers, including his tutors in the British Navy, Heihachiro Tōgō by contrast, was a quiet, introverted, silent man with a rather melancholy face, which lit up when the spirit moved him, by the sweetest of smiles. Tōgō took to heart all he had learned during his naval training in Britain. But one thing his tutors at the British Naval Academy would not have been aware of was Tōgō’s fierce attachment to his own country, an unstable blend of entitlement and insecurity shared by his countrymen that metastasised 60 years later in bitter Japanese resentment of Britain and its Far East colonies.

Yes, British sailors of all ranks were loyal to King (or Queen) and country, and obeyed strict discipline on their ships, even if only persuaded to do so under the bitter lash of the cat o’nine tails. But they lacked the spiritual dimension of the Japanese sailor. Also, presumably, any sense of condemnation from their mates. If the British tar failed to perform his duty, he would bear his punishment stoically. But he lacked the sense of shame and ostracism inflicted on the Japanese sailor by his comrades, a characteristic that applies to all classes across Japanese society.

Nor was the British tar imbued with the same unfailing obligation, bordering on mysticism, that Japanese sailors of all ranks owed to their Emperor. Meiji was, after all, the direct descendent of Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess, and thus carried with him the divine right to rule as a God himself. Nor did the British tar have anything like the blessings that were bestowed on his Japanese counterpart. If he died in battle, the Japanese sailor was elevated to the pantheon of war heroes interred forever in the vaults of the Yasukuni Shrine. For to die in battle was glorious. Indeed, the Japanese Navy modified the British tradition that the captain be the last to leave his ship to the exhortation that the captain must go down with his ship.

And Tōgō’s private life? Tōgō seems not to have experienced the same kind of dalliances as Nelson. He married a quiet and intelligent woman called Tetsu Kaeda, and had two sons with her. Unlike Nelson, nothing of any affair outside his marriage appears on the records I have had access to. But this is not to assume that, like many successful Japanese males, Tōgō did not participate in traditional geisha parties and enjoy the charms of their hostesses. Unlike adulterous liaisons in Europe, these did not have the smell of scandal about them, and were broadly accepted in traditional Japanese society.

One thing however, is certain. Tōgō had great admiration for Nelson, and his emulation of the First Sea Lord was deliberate. To quote from historian Stephen Howarth in his excellent history of the Japanese navy, Morning Glory:

“Tōgō’s triumphant return to Tokyo after Tsushima, took place, from his own choice, on 21 October 1905 – the hundredth anniversary of the Battle of Trafalgar. It may be, too, that in his understandable desire to echo Nelson, still the spiritual apogee of admirals, Tōgō had hoped he might actually die during his greatest battle. As it was starting, his officers had tried to persuade him to leave the bridge for the greater security of the conning tower, but he had refused, saying ‘I am getting on for sixty, and this old body of mine is no longer worth caring for.’ That he survived was pure luck; he himself was wounded slightly, and men were killed so close to him that his beard was splashed with their blood. And if he missed the chance of re-phrasing Nelson’s last words, ‘Thank God I have done my duty,’ which would have been both legitimate and appropriate, at least the Japanese nation was also able to avoid echoing Captain Blackwood’s words of a hundred years earlier – ‘On such terms, it was a victory I never wish to have witnessed.”

Perhaps the praise Tōgō most appreciated was from Jackie Fisher, who said:

“In the fleet the Admiral’s got to be like Nelson, so it was that Tōgō won the second Trafalgar.”

In the decades following Tsushima, many of the world’s naval strategists continued to be wedded to big gun battleships, even as the First World War began to expose their vulnerability to aerial attack. Japanese strategists were highly indignant that Japan was reduced at the Washington Naval Conference in 1922 to limiting the tonnage of their battleships to 35,000 tonnes each, and their ratio to three against five for Great Britain and five for the United States. In defiance, they built such behemoths as Yamato and Musashi, each of over 72,000 tonnes, carrying nine 18- inch guns, the largest and fastest battleships the world had ever seen.

If, instead, Japanese planners had learnt the lessons of history, and spent more effort building more aircraft carriers, Japan might have retained the capacity to resist for much longer America’s ineluctable advance across the Pacific in 1944-45. After all, it was Japanese carrier-based aircraft that sank Britain’s battleship Prince of Wales and battle cruiser Repulse off Malaya on 10 December, 1941. They were the first two capital ships in naval history to be sunk solely by air power on the open sea.

I like to think that if Heihachiro Tōgō had retained his authority and intellectual vitality for even five years before his death in May 1934, he may have persuaded Japanese planners to discontinue the folly of building such battleship dinosaurs, and build as many aircraft carriers as possible before the Pacific War began.