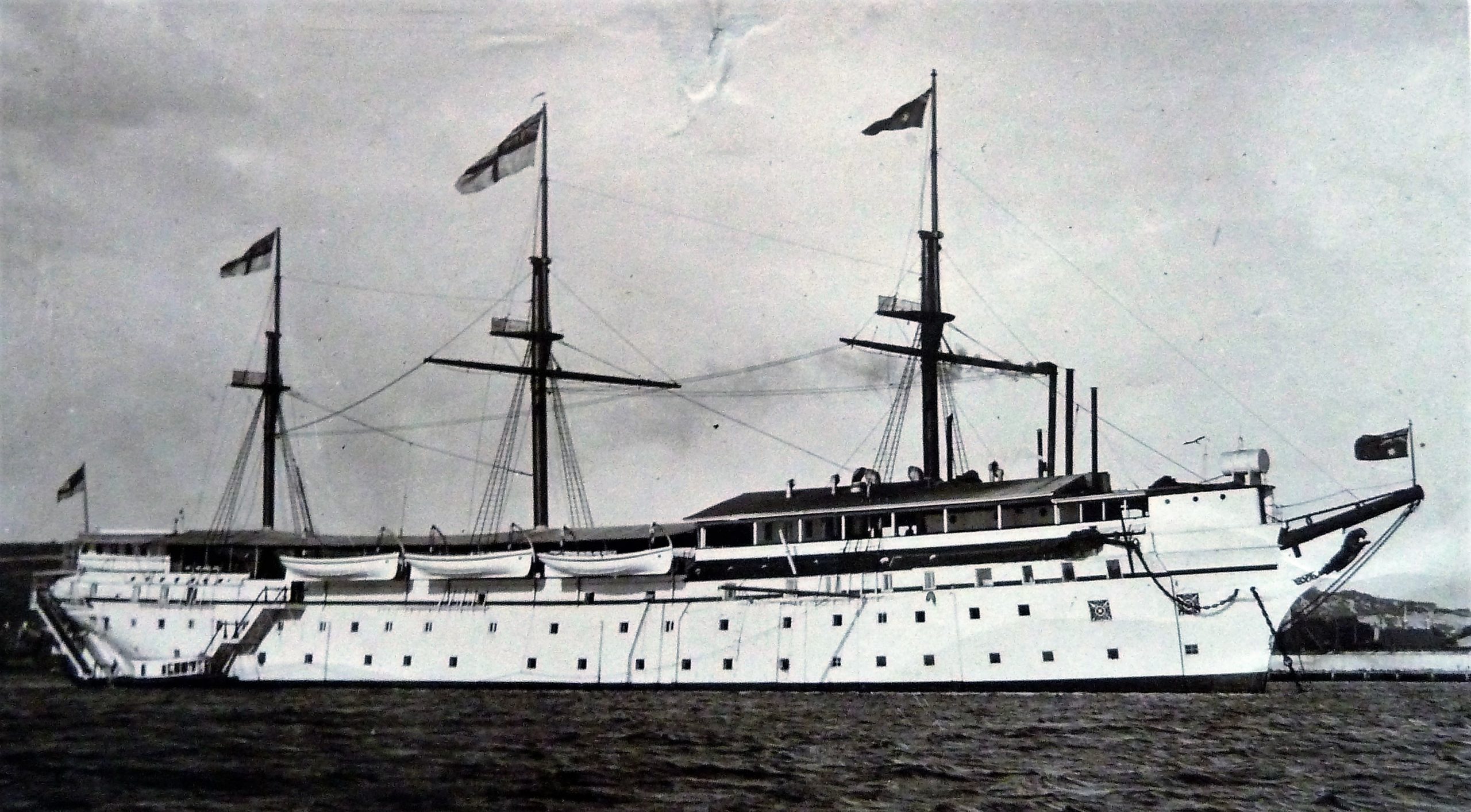

On Wednesday, 1 October 1913 the Sydney Mail newspaper featured the following detailed report on early naval recruiting and training. Just three days later, on 4 October, Sydney Harbour would provide the venue for the arrival of the first RAN Fleet unit, led by the flagship and battlecruiser HMAS Australia. To help train the personnel for this ever-growing naval force, a 46-year-old sailing ship had been purchased the previous year for conversion to a static training ship, anchored in Rose Bay. Originally named Sobraon, she was structurally altered for her new role at Morts Dock at Balmain in Sydney and commissioned as HMAS Tingira on 25 April 1912.

HMAS Tingira

If he were asked upon which of his ships the success of the Royal Australian Navy really depended more than on any other – which ship was really more important to the future defence of Australia than any other – anyone who was really acquainted with the subject would probably reply: HMAS Tingira.

For the future of our navy at this present moment depends upon this one question: Will the Australian turn into the first-class seaman, the smart, active, obedient, intelligent, well-disciplined man that is absolutely necessary if the navy is to be a success?

And the boys of whom the highest results are expected, of whom their instructors and officers and those who have seen them at their work say “Yes” when the above question is put to them, are the boys who enter the Navy through the training ship Tingira. Not all the recruits enter the ships of the navy through Tingira – only a comparatively small proportion of them. There is another door by which a young man can enter it at a later age, through the training depot at Williamstown in Melbourne. There is a training establishment there, at which 400 young stokers and seamen are receiving their first naval training and their special training as signalmen, cooks, telegraphists, and so on. Any young man between 17 and 25 may join the navy there for ‘short service’ of five or seven years, at the end of which time they may re-engage for further periods of five years. The run on those schools this year was so great that the whole of the accommodation was filled up, and when the men had overflowed into the reserve barracks the ages of entry had to be temporarily narrowed down by three or four years. That is how the greater number of young seamen and stokers have recently entered the navy.

But this method undoubtedly has one drawback. An Australian by the time he is 17 or 20 years of age has usually become accustomed to a pretty complete absence of restraint, which he cannot ‘possibly hope to find in the navy. As it has recently been put by a journalist who has seen something of the Australian seaman, he is apt ‘to look upon routine as bullying.’

Now, the pay is high in the Navy, a little higher than the pay on shore, when all things are considered. The chances of promotion in it are good – the naval service offers a career, which it certainly never did before, and is therefore attractive to young Australians. But no man should enter it unless he is prepared to submit to discipline and to routine. Those who have determined with themselves to take these things as part of the game, have made splendid seamen and will make a career in the navy. But those who have not had better choose a different career.

Boys of Quality

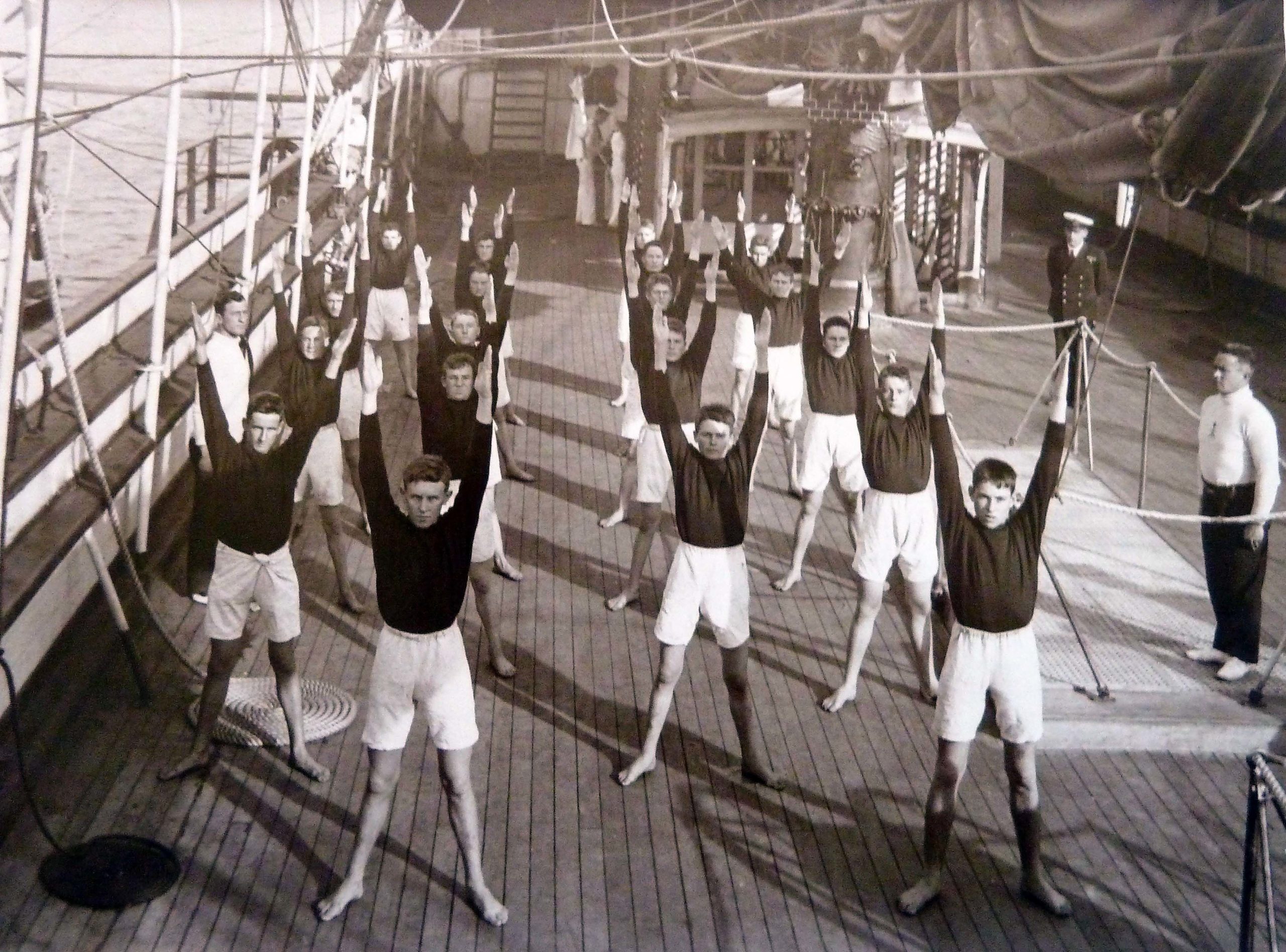

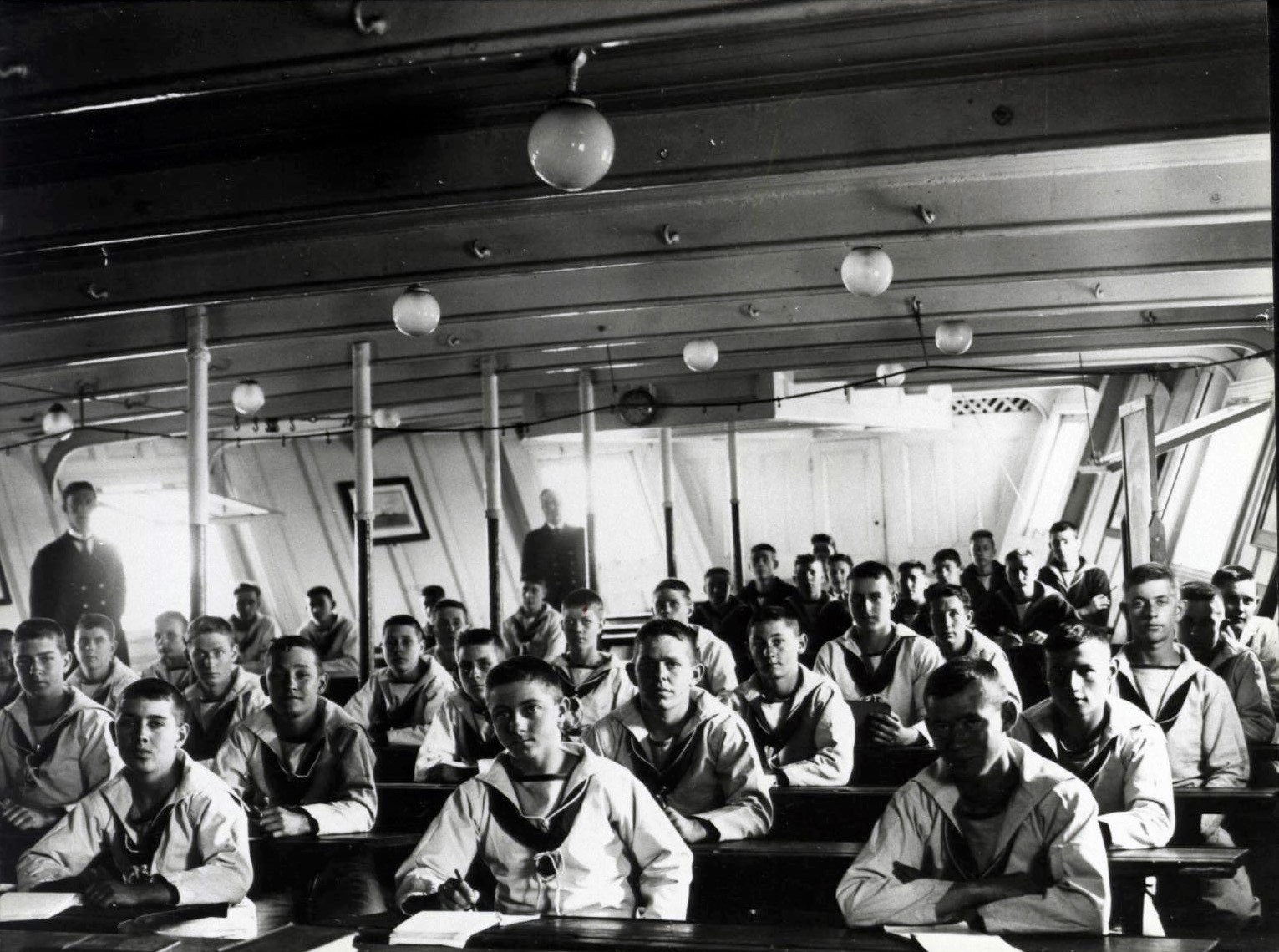

On the other hand, the boys who enter through Tingira enter at quite a different age – from 14 years six months to 16 years (engaging to serve until they are at least 25) – and their case is a very different one. The Navy Board wisely decided from the first to make that school a magnificent one; to make it a testimony to a boy’s character that he should be able to say: “I am serving in the Navy’s training ship.” It was decided that boys must be ‘of very good character’ before they could be taken as candidates for Tingira. No boys who have been in prison or in reformatories are to be admitted there.

The result of this wise decision is that Tingira has been filled with boys of splendid quality. “It is quite possible,” said a high authority recently, “for one son of (say) a clergyman’s family to be on Tingira, and another in the Royal Naval College.” It is a magnificent training that is given these boys and the country undoubtedly looks to these Tingira boys to set the tone and the standard in the fleet, when they reach it. That is the duty of Tingira, and for that reason it is impossible to over-estimate her importance in the Australian naval system.

The chief problem before the Australian authorities, the problem which Canada failed to solve, was long foreseen to be the finding of the men and of the right sort of men. The Navy Board decided to solve it by two means: firstly, by making service in the navy a modern profession and paying the men slightly more, when their upkeep, etc., is considered, than in the ordinary professions ashore; secondly, as a means of keeping the service alive, by holding open for the keenest and best men an avenue to higher posts such as would make the service a career worth considering by any ambitious Australian.

HMAS Tingira as RAN Boy’s Training Vessel 1914 – Naval Heritage Collection

HMAS Tingira Boys in class room, Naval Heritage Collection image #10651

Further Reading

H. J. Thurston, The History of HMAS Tingira, September 1979 edition of the Naval Historical Review

Greg Swinden, HMAS Tingira; Legacy Of Service (1912-1927), December 1991 edition of the Naval Historical Review

Greg Swinden, The Tingira Tram, March 2011 edition of the Naval Historical Review