By David Michael

As experience continues to demonstrate, major conflict and wars not only affect those living in the immediate area of operations but regionally and often globally. These conflicts disrupt lives, economies and trade, in particular the availability of commodities and supply lines. Similarly new supply lines must be established to support forces engaged in conflict. Given the nature of war, front-lines ebb and flow sometimes rapidly and at other times agonisingly slowly. Thus, the impact on individual people, towns and cities varies from the long term to the fleeting.

When considering the impact of conflict on the people of North Queensland in major wars it is clear that in major centres such as Townsville during World War II and to a lesser extent during the War in Vietnam the effect was significant. Fortunately, it was not significant in terms of casualties despite being bombed on three occasions in July 1942.

During the War in the Pacific, Townsville played host to more than 90,000 allied service personnel. The whole city became a virtual air force and military base. It was a major offensive launching base during the battle of the Coral Sea and a logistics hub for the resupply of allied forces fighting in New Guinea.

In contrast to the long three-year impact of support operations on Townsville the impact on the Palm Island group just 65 kilometres north of Townsville was limited. For just one week in the early days of World War I it hosted the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (ANMEF). During World War II it was utilised as a minor operating base for cruiser-destroyer forces patrolling off northeastern Australia and ashore it hosted support facilities for US Navy seaplanes for a period of several months.

The Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force Visit: September 1914

Following the United Kingdom’s declaration of war upon Germany on 4 August 1914 Australia chose to go to war in support of Britain and to secure its own position in the world. Thus, Australians were committed to ensuring Germany did not dominate Europe and the trade routes of the British Empire. Within days of the Declaration Australian forces deployed to eliminate the German colony in New Guinea and remove Germany from the Pacific region. This historic first operation for the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is even more significant given that the RAN was formed just three years earlier and was operating ships which had been acquired and commissioned less than one year earlier.

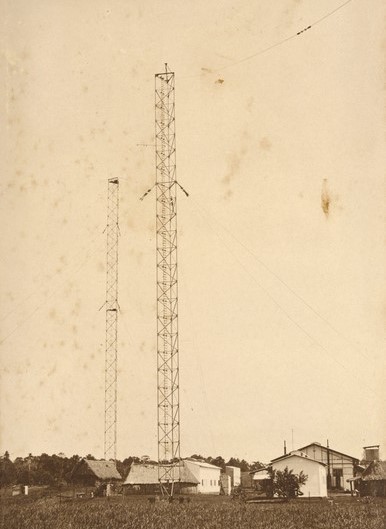

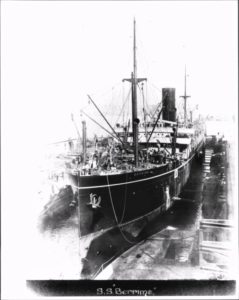

For this inaugural operation the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (ANMEF) was formed at short notice and sent to Rabaul on the island of New Britain to seize German wireless stations. Recruiting began on 10 August 1914 and less than ten days later Colonel William Holmes DSO had recruited, equipped, and embarked a 1,000-strong infantry battalion and 500 naval reservists and ex-seamen. The naval reservists were drawn from Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia. Due to the urgency of organising the force, the military component was enlisted only from New South Wales. The ANMEF left Sydney on 19 August aboard HMAT Berrima escorted by HMAS Sydney and HMAS Encounter.

As the whereabouts of German naval squadron based in China was unknown, strict orders were given by the Commander of the Australian Fleet, Rear Admiral Sir George Patey that the expedition was not to proceed north of Palm Island without a strong naval escort. Accordingly, Berrima and her escorts arrived at Palm Island on 23 August to await additional support for the onward passage to Port Moresby and New Britain.

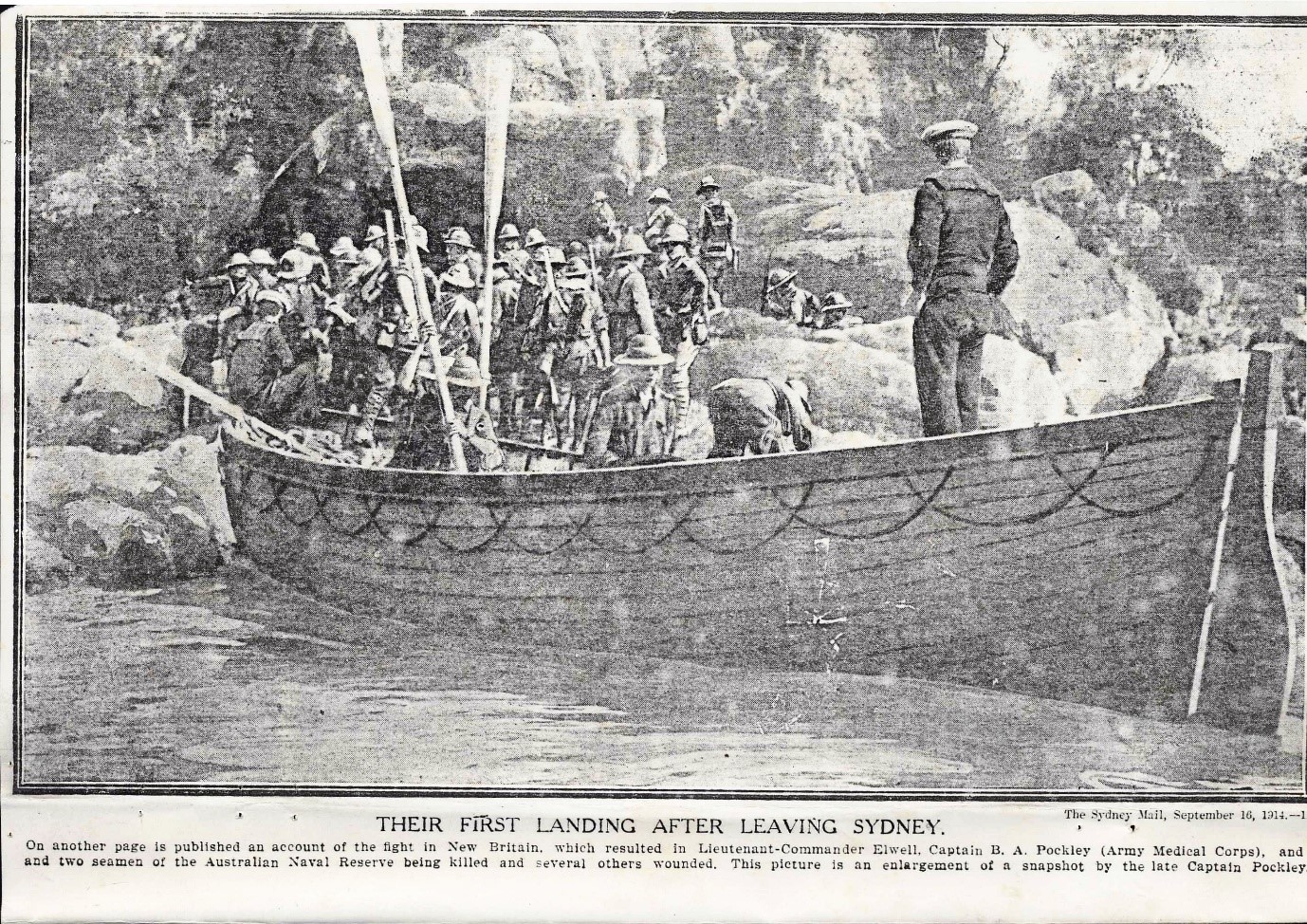

The time spent waiting off Palm Island proved to be an important opportunity for the men of the ANMEF to rehearse landing ashore by boat and to hone their musketry and field skills. The first of five landing rehearsals was conducted on 24 August. Once ashore mock attacks were conducted in thick, tropical bush country with the landing force back onboard overnight. The establishment of a firing range ashore facilitated important marksmanship training which was to be used just days later when actual landings were conducted on 11 September. Communications in thick country was another essential infantry skill honed on Palm Island and critical for success in the dense jungles of New Britain.

On 2 September the ships departed Palm Island for Port Moresby to rendezvous with other vessels involved in the operation and to make final plans for the attack. The whole force included seven vessels of the RAN’s Australian Squadron and five merchant ships of which four were colliers and the supply ship Aorangi.

The attack on Rabaul and the Battle of Bita Paka to destroy its radio station were successful but at the cost of Australia’s first World War I casualties. Six Australians were killed in the Battle of Bita Paka after encountering a force of German and Melanesian policemen. These battles were the initial phase of the invasion and subsequent occupation of German New Guinea.

World War Two

In contrast to the relatively rapid capitulation of German forces in the Pacific during WWI, ejecting Imperial Japanese forces from occupied territory in WWII was protracted and costly in terms of casualties. The Kokoda Track campaign (July to November 1942) is an example of the ferocious battles most Australians are familiar with. Kokoda was followed by the Battle of Buna-Gona (November 1942 to January 1943) to eject Japanese forces from the beachheads from which their Kokoda campaign had been launched.

Task Force 74

The resupply of Australian and US troops by both air and sea in this battle was particularly treacherous.. The supply line originated in Townsville from which large vessels formed convoys for passage to Port Moresby and Milne Bay under escort. This resupply operation was called Operation Lilliput[1]. This force, known as Task Force 74 was a mixed Allied force of Royal Navy, Royal Australian Navy, and United States Navy ships. They conducted patrols throughout the South West Pacific and escorted convoys. In late 1942 during the New Guinea campaign, Palm Island served as a minor operating base for Task Force 74 ships.

At this time Australian ships assigned to Task Force 74 included HMA Ships; Australia (the Flagship), Canberra, Arunta and Warramunga.

These ships spent time in the vicinity of Palm Island awaiting merchant ships forming convoys bound for New Guinea.

US Naval Air Station

Palm Island’s main function during late 1942 to 1943 for the US Seventh Fleet, South West Pacific was as a major patrol plane base. In early 1943 the US Navy decided to build the air station at Palm Island. It was to have facilities to allow it to operate and overhaul seaplanes and patrol boats. The Air Station overlooked Challenger Bay which featured a large stretch of sheltered water which was ideal for flying boat operations. A downside of the site was the very rugged terrain which exists right from the water’s edge.

On 6 July 1943 two officers and 122 enlisted men of Company “C” of the 55th Seabee Construction Battalion left Brisbane to start construction of the Air Station. A short time later a similar detachment left Brisbane with 1,500 tons of construction material for construction of the 1,000-man camp at Wallaby Point. Concrete flying boat ramps to the ocean were constructed along with a large tarmac parking area for up to 12 flying boats. Moorings for 18 flying boats were provided in Challenger Bay and work was commenced on 3 nose hangers. The Seabees used coral aggregate from coral reefs to manufacture concrete.

A Tank Farm with a capacity of 60,000 barrels of aviation fuel was built and steel rail lines installed to launch the Catalina flying boats back into the water. These steel rails have now almost totally disappeared, either rusted away or covered with sandbut on or near Palm Island today are the remains of several Catalinas and unexploded ordnance is also sometimes found by residents.

With the large number of operational and maintenance personnel in place the Air Station commissioned on 25 October1943. From then until 1 May 1944 Palm Island averaged the overhaul and repair of four seaplanes a day. Closure began on 1 June 1944 with the facilities dismantled for shipment to forward bases with the air station formally disestablished in July 1944.

References

Stevenson Robert, Australia’s First Campaign, The Capture of German New Guinea, 1914 published by the Army History Unit

Pfennigwerth Ian, Under New Management, The Royal Australian Navy and the Removal of Germany from the Pacific, 1914-15 published by Echo Books.

Naval Historical Society of Australia, Battle of Bita Paka 11 September 1914, Occasional Paper 14 published September 2017 available at file:///M:/Naval%20Historical%20Society/Newsletter%20Monthly%20Electronic/Occassional%20Papers/Occassional%20Paper%2015_Battle%20of%20Bita%20Paka%20_September%202017.pdf

Gill Hermon G, Royal Australian Navy 1942 to 1945

Coletta Paolo E, Editor, United States Navy and Marine Corps Bases, Overseas published by Greenwood Press

Perryman John, The Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force – First to Fight, 1914 published by the Sea Power Centre – Australia available at, https://www.navy.gov.au/history/feature-histories/australian-naval-and-military-expeditionary-force-first-fight-1914

Palm Island Naval Air Station During WW2, Ozatwar website, https://www.ozatwar.com/airfields/palmislandnavalairstation.htm

[1] Operation Lilliput was the name given to a convoy operation for the transportation of troops, weapons, and supplies in a regular transport service between Milne Bay and Oro Bay, New Guinea between 18 December 1942 and June 1943. The objective was to “to cover reinforcement, supply, and development of the Buna-Gona area upon its anticipated capture” by the Australian 7th Division and the United States Army’s 32d Division.