By Geoff Barnes

This story first appeared in ‘All Hands’, the quarterly volunteers’ journal at the Australian National Maritime Museum. Our thanks to the ANMM Volunteers for allowing us to republish it.

Desirable, Affordable and Appropriate

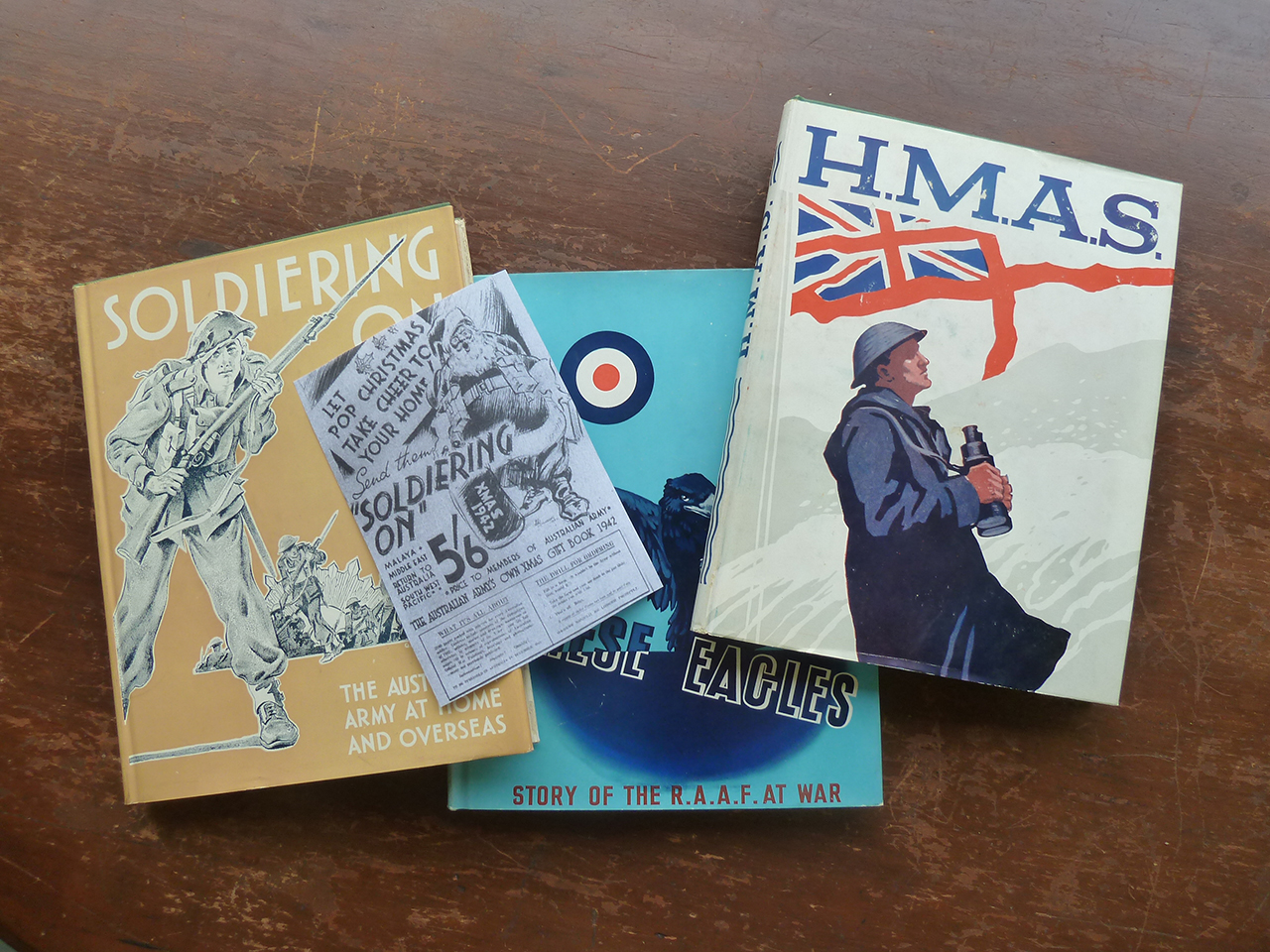

It’s December 1942, and Australia’s armed services are scattered all over the world; in the Middle East and the South West Pacific, flying over Europe, sailing the Mediterranean. And what do you do about presents for the families and friends back home? ‘Let Pop Christmas Take Cheer to Your Home’ said the pamphlet sent to servicemen and women. ‘Send them Soldiering On, the Australian Army’s Own Xmas Gift Book for 1942, price to members of the Australian Army 5/6d.’

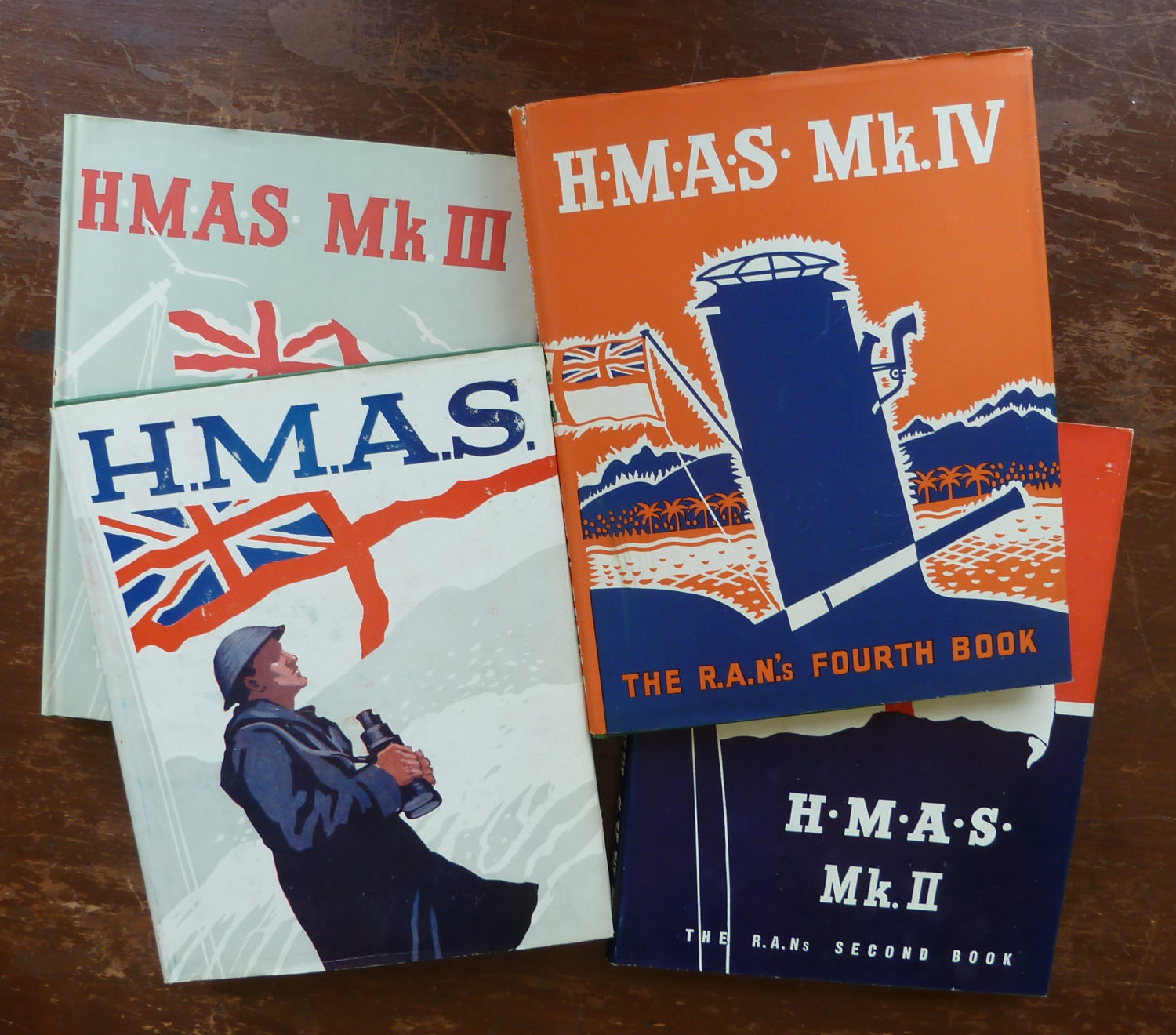

Or These Eagles. Or HMAS. The three services each had a book. The pamphlet stated that ‘The drill for ordering is simple. Take your paybook to the pay bloke. Fill in a form. (It’s wouldn’t be the army/air force/navy without that, would it?) That’s all. Relax.’ Job done, and you have sent your loved ones a serving person’s souvenir. It has information. It has humour. It has quality. And it will give them something to think about, because it was written by men and women who know what it’s like out here.

When I proposed this story to the All Hands editorial group, I was surprised that some had never heard of these books. They were produced by the Australian War Memorial, fourteen during hostilities and five after the war. All in all, including a number of reprints, almost two million were published and sold to a country whose population was barely seven and a half million. The Christmas books were a phenomenal success. The right product for a captive market, but they happened only because of a unique driving force – John Treloar.

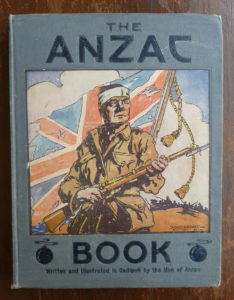

In 1941, John Treloar, the tireless and entrepreneurial Director of the Australian War Memorial suggested publicising illustrated books about the Australian armed forces during the Second World War. They would be modelled on a highly successful book published in the Great War. Charles Bean, the war correspondent and historian, and the man who conceived the idea of a national war memorial, published a book about Gallipoli. It was written and drawn by men in the ANZAC Cove trenches, created by soldiers coping with a determined enemy, extreme hardship, terminal tedium and an excess of apricot jam. The illustrations, stories, jokes, cartoons, and poems were intended as a Christmas and New Year diversion for soldiers about to face a harsh winter in the Peninsular trenches. Paper was scarce, and contributions were scribbled on ration labels and cigarette packets.

When cartoonist David Barker ran out of water-colour paints, he used mercurochrome and iodine from a first-aid kit. Proceeds would be for ‘the benefit of patriotic funds connected with the A. & N.Z.A.C.

But professional publication took time and the ANZACs had retreated from the ‘damned Dardanelles’ by the time it became available. However, The ANZAC Book was arguably the finest ‘trench publication’ produced during the Great War. It was an instant bestseller when first released in 1916; a treasured gift to their families back home.

Treloar proposed to the Museum Board that the World War II Christmas books would follow that pattern, written in popular style, lavishly illustrated and containing a strong personal element. Money raised by the books would go towards the completion of the Memorial building in Canberra which, unlike the cashed-up memorial today, was struggling for funding. They would be published each Christmas in a time when (a) money was a lot tighter and households weren’t buried in unsolicited gifts of dubious value and (b) almost every home had been touched by the war and (c) there was a ready market. As a consequence, the Christmas books would be seen as desirable, affordable and appropriate gifts from those who were serving. And patriotic, too, in days when patriotism wasn’t just political jargon.

A Phenomenal Success

The Memorial published the first Christmas book, Active Service in 1941, with an initial print run of 94,531 copies. This was the largest print order in Australian history at the time. Of the twenty books published, Jungle Warfare was the highest selling title, with sales of 230,407 for its first print run. The army had the greatest numbers so that boosted the sales, but the other services did well, too. The four volumes about the RAN, published each year from 1942 to 1945, were highly popular.

The Driving Force

Why was this enterprise undertaken by the Australian War Memorial?

As Australia entered the Second World War the Memorial in Canberra was still not complete. It was dedicated to the First World War, or ‘the Great War’. No one who had experienced the appalling carnage and loss could imagine that the world would be insane enough to do it all over again two decades later. When World War II broke out there was considerable high-level Board and Government opposition to including this lesser ‘postscript’ in the Memorial concept, but as it became apparent that the new war was going to be of a comparable scale, it became inevitable that the Memorial’s scope should be extended and encompass a whole new set of conflicts.

Two men, above all others, had shaped the Memorial: the war correspondent and dedicated ANZAC historian Charles Bean who had the dream of a memorial to the men and women who had served in the Great War, and John Treloar, who contributed more than any other person to the realisation of Bean’s vision. Treloar had landed on Gallipoli on 25 April 1915. In 1917, as a captain, he was appointed to head the newly created Australian War Records Section (AWRS) in London, responsible for collecting records and relics for the future museum and to help Bean, the official historian, in his work. Treloar’s energy and capacity for hard work made him a fitting choice to become the Director of the Memorial – the AWM- between 1920 and 1952.

After the First World War it took a long time before the AWM was actually built. Initially there were delays in drumming up public and government enthusiasm. Then the financial crash and the subsequent Great Depression intervened. In the meantime, large and long-running temporary exhibitions were held in Melbourne and Sydney. But as far back as 1918 Bean had imagined a permanent home in the new national capital of Canberra. It would be gallery, museum, archive, a publishing house, and above all else, a memorial. And it would also be expensive.

The Memorial’s design was a compromise between the desire for an impressive monument to the fallen and a budget of only £250,000. The design that was finally accepted forms the basis of the building we see today, which was completed and opened to the public on Remembrance Day, 11 November, in 1941, barely a month before the Imperial Japanese Navy attached Pearl Harbour.

Meanwhile in 1941 John Treloar was pleased to be back in uniform, forty-seven years of age, appointed lieutenant-colonel and despatched to the Middle East to ‘collect material for inclusion in the memorial’. But this was a very different war, far less static than the Great War. The Australian soldier was soon involved in a war of movement as the Italians, Germans and Allies chased each other back and forth across the desert. Little time to collect souvenirs. Treloar decided on an imaginative approach that would have more immediate impact for the AWM.

Easier Said Than Done

He decided to create a second world war equivalent of The Anzac Book, with the help of the members of his Military History Section and the other newspaper correspondents, photographers and artists covering the war, plus contributions from the troops themselves. It would follow Bean’s idea of a 1942 Christmas book for the troops to give to their families. Time was against him, and the product was not as polished, but the appeal would be such that it set the pattern for the Christmas books to come, which would be more rigorously edited and complied. They would all carry the proud banner line ‘Written and produced by Serving members of the Armed Services’.

Treloar asked the War Memorial Fund to provide the £2250 needed to publish back in Australia, at a time when the Memorial was right in the middle of preparations for its official opening. He was still overseas, trying to coordinate with Halstead Press, a division of Angus and Robertson. Halstead had just received the order for On Active Service. It was the company’s biggest ever printing job with a crushing schedule and a wartime shortage of paper and trained staff. It was 4th November and there seemed no hope of producing 16,000 books before Christmas. To add to the considerable headache, they were also trying to finish the guidebook for the AWM opening a week later. Treloar, on the practical side, had two bookbinders released from training camp, and on the emotional side, played the ‘damage to troops morale’ card, given that they had already stumped up their five and sixpences.

All the troops’ orders for Active Service were not filled until March 1942, but when it did eventually appear the reviewers found much to admire, and given that it contained sensitive war art and stories in a time when censorship was heavy, it was a remarkable achievement that it appeared at all. A few of the contributions were acknowledged but most were published semi-anonymously, using only the contributor’s serial number to identify the author or artist. Some were actually recognisable names in the arts and literature. Others faded from memory after their brief glow in print.

The literary and artistic entries were submitted by service personnel to the Service Christmas Annuals competition sponsored by the Australian War Memorial. The competition was vetted by the Military History Section, with John Treloar at its head. Now back in Australia, Treloar played a vital overseeing role in compiling and producing each Christmas book and, of course, providing a healthy revenue stream for the Memorial. Whether these annuals absorbed too much of Treloar’s energies was a matter never really considered by the Memorial’s Board of Management nor the Army. The fact that he carried on this publishing enterprise in addition to a full-time job as head of the government’s Military History Section almost defies belief. However, he did write to a close colleague ‘I am beginning to regret that I ever suggested we should commence to publish an Army Christmas Book’.

Table of Contents

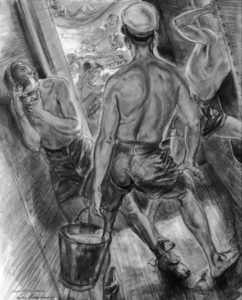

Some of the contributors, particularly in the artwork, were always going to be professionals who had been appointed as official war artists. Most, however, were creative people thrust into extraordinary circumstances and being inspired to celebrate, satirise and commiserate about life in the armed services.

The Editor of all four HMAS books was Lieutenant Commander G. Herman Gill, R.A.N.V.R. who selected the artwork and photographs, and wrote most of the operational narratives. Each volume had a small team of Navy personnel who worked for the Military History Section.

Take HMAS Mk. II, for example.

In the Foreword Admiral Guy Royle, as Chief of the Naval Staff, ‘endeavours to give something of a picture of this world-wide fabric of sea power, and the threads therein woven by the Royal Australian Navy’. The operational overview of Australia’s involvement in the world-wide conflict stresses the nation’s benefits and perils from being an island adrift in hostile waters. That’s the serious part.

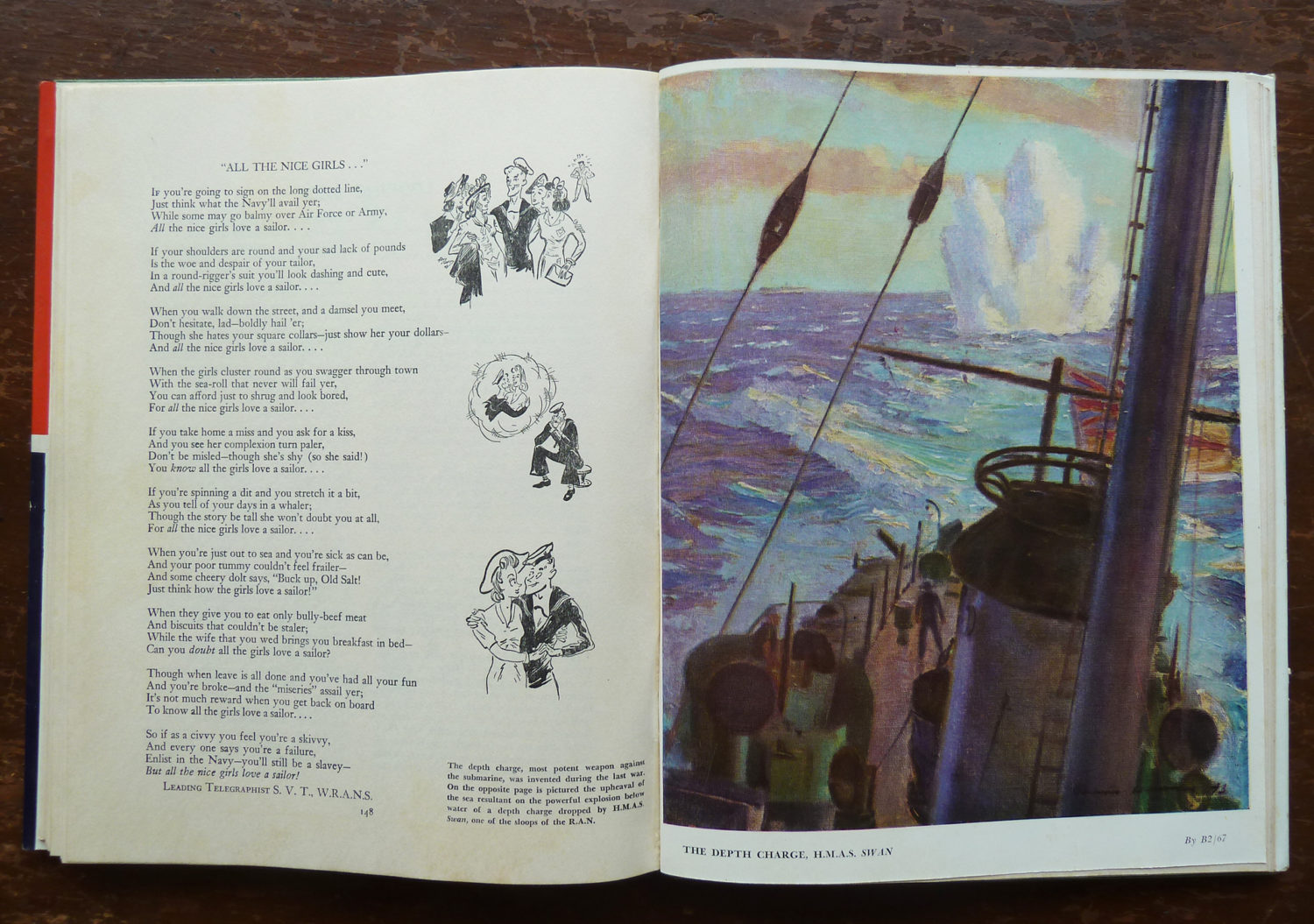

Then follow more personal contributions. Some are brief, and none except the operational essays exceed a couple of pages. There are over thirty entries in this volume; stories, paintings, poems, sketches, but supplemented with photographs from Treloar’s Military History Section, and much of the art work is from the Memorial’s official war artists.

Turning the Pages of HMAS Mk. II

Some examples.

‘Wavy Navy’ R.A.N.V.R. Lieutenant-Commander J.S.B. tells a stressful, perilous and sometimes hilarious tale of a fund-raising road trip as he escorts the wreckage of the Japanese midget submarine around rural Australia. Signal Boatswain C.H.N. writes an ode to a stolen pencil. Paymaster F.L.S. tells a less-than-flattering tale about a US naval man at a pawnbroker’s shop. Lieutenant F.B.W. explains how the ship’s cat always got fresh milk while the human personnel made do with tinned. There’s a cartoon of a sailor on a raft viewing the jaws of the surrounding sharks and noting that his toothpaste went down with his ship. Another tells the story of surviving a torpedo-ing in a laconic fashion. No false heroics here.

This sample from Signalman G.W.W. gives a fair representative of the style.

‘This is a little story about Cyril F…, a shipmate of mine and a downright pain in the neck. He was a cross between a Chicago yegg and a George Street gigolo, standing 6 feet 3 inches in his Comforts Fund sox with strength to match. Before the war he earned a humble living tossing wool bales around a waterfront warehouse, and exercised nightly at a gym. His relaxation and only vice was Boris Karloff, Hopalong Cassidy and Superman, all viewed and worshipped at the local cinema. A simple soul was Cyril. He walked ashore one evening with the firm intention of seeing the latest thriller, but somehow got the theatres mixed, and he wound up at a show called “The Commandos Strike at Dusk”. When he returned, Cyril was a changed man. The light of ambition burned brightly in his eyes. Briefly he dropped the verbal bombshell in the mess – “I’m gonna leave the navy and be a commando” …’ The tale that follows is a delight.

In contrast, Cadet Rating P.G.M. in a sentimental but slightly awkward poem tells of two fellow Cadets lost at sea. There’s a page showing candid photographs of HMAS Kanimbla’s ‘crossing the Line’ ceremony. Another showing cas-evac at sea. Lieutenant W.N.S. tells about shipyard workers in the complex business modernizing his ship, HMAS Riverina. There’s a hoary old tale about searching for striped paint and applying to the Chief Buffer for an ‘optional shirt for tropic rig’, and a painting of a dive-bomber attack. A Leading Writer tells a tale of brief action stations aboard the little ship like the corvettes, but mostly the interminable routines of a routine patrol.

Who Were They?

Only in HMAS Mk. IV, the RAN’s fourth book published in 1945, were the contributors finally identified. There are 400 of them, from admirals to ordinary seamen and women. The Editorial in Mk. IV begins with these words.

‘With this present volume we close the series of books chronicling the achievements of the ships and personnel of the Royal Australian Navy in the late war. I putting a conclusion to this task, a feeling of regret is inescapable…We apologize for the delay in production on this occasion. Various factors contributed – and for those of you who have become impatient we would say, “Don’t you know there’s a peace on?” The conclusion of hostilities set us back, since we wanted to get everything clewed up with surrenders and so forth. Then demobilization delayed us, and what with one thing and another we got badly astern. But here we are at last and none the worse, we hope, for overstaying our leave.’

Sources:

AWM publications HMAS Mk. I (1942), Mk. II (1943), Mk.III (1944) and Mk. IV (1945).

Michael McKernan, ‘Here is Their Spirit -a history of the Australian War Memorial 1917 -1990’, University of Queensland Press in association with the Australia War Memorial, 1991.

Craig Collie, ‘On Our Doorstep’, Allen & Unwin,2020.

National Archives of Australia.

Australian War Memorial Research Centre.

Australian Dictionary of Biography.

Wikipedia.