by John Jeremy

The designation ‘Building 10’ will be meaningless to most people, yet thousands will have seen this Building 10. It stands on the upper level of Cockatoo Island in Sydney and has more commonly been known as the Drawing Office building. Whilst it is amongst a number of nondescript grey buildings it is easily identifiable because it is painted green. With a history of shipbuilding and ship repair encompassing 134 years, the 17 ha Cockatoo Island, a World Heritage site, lies at the junction of the Lane Cove and Parramatta Rivers and is now in the care of the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust for the people of Australia.

With an early history as a convict prison, ship repair began on Cockatoo Island in 1857 with the opening of the convict-built, and now World Heritage listed, Fitzroy Dock. Shipbuilding began on the island in 1870. One hundred and ten years ago, about eight months before the outbreak of World War I, the island was purchased from the NSW Government by the Commonwealth Government and it became the Commonwealth Naval Dockyard — the first naval dockyard of the new Royal Australian Navy.

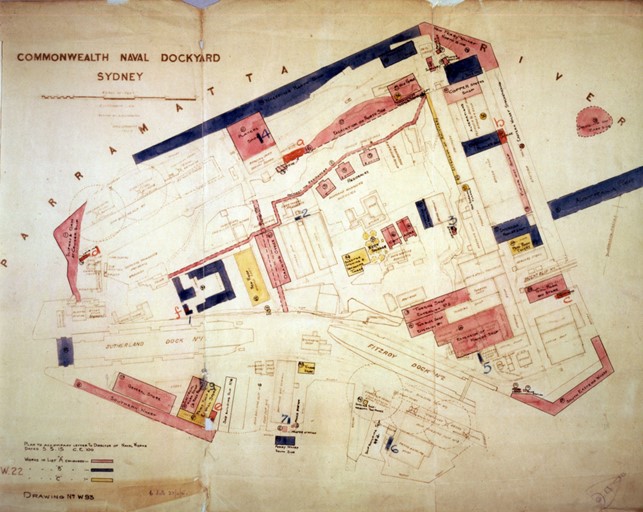

This plan of Cockatoo Island shows the ‘wish list’ of the new Commonwealth Naval Dockyard. Dated 5 May 1915 it shows the proposed drawing office building in red near the centre of the island directly above the tunnel from the head of the docks to the northern shipyard. Not all of the proposed work was completed, including the ambitious Australia Pier on the eastern shore of the island

The NSW Government had embarked on a program of development of the island’s facilities after Federation, but with the demands of the war and the construction of three destroyers and a cruiser, HMAS Brisbane, further expansion of the dockyard was urgently needed. Amongst the new facilities required was a new drawing office building.

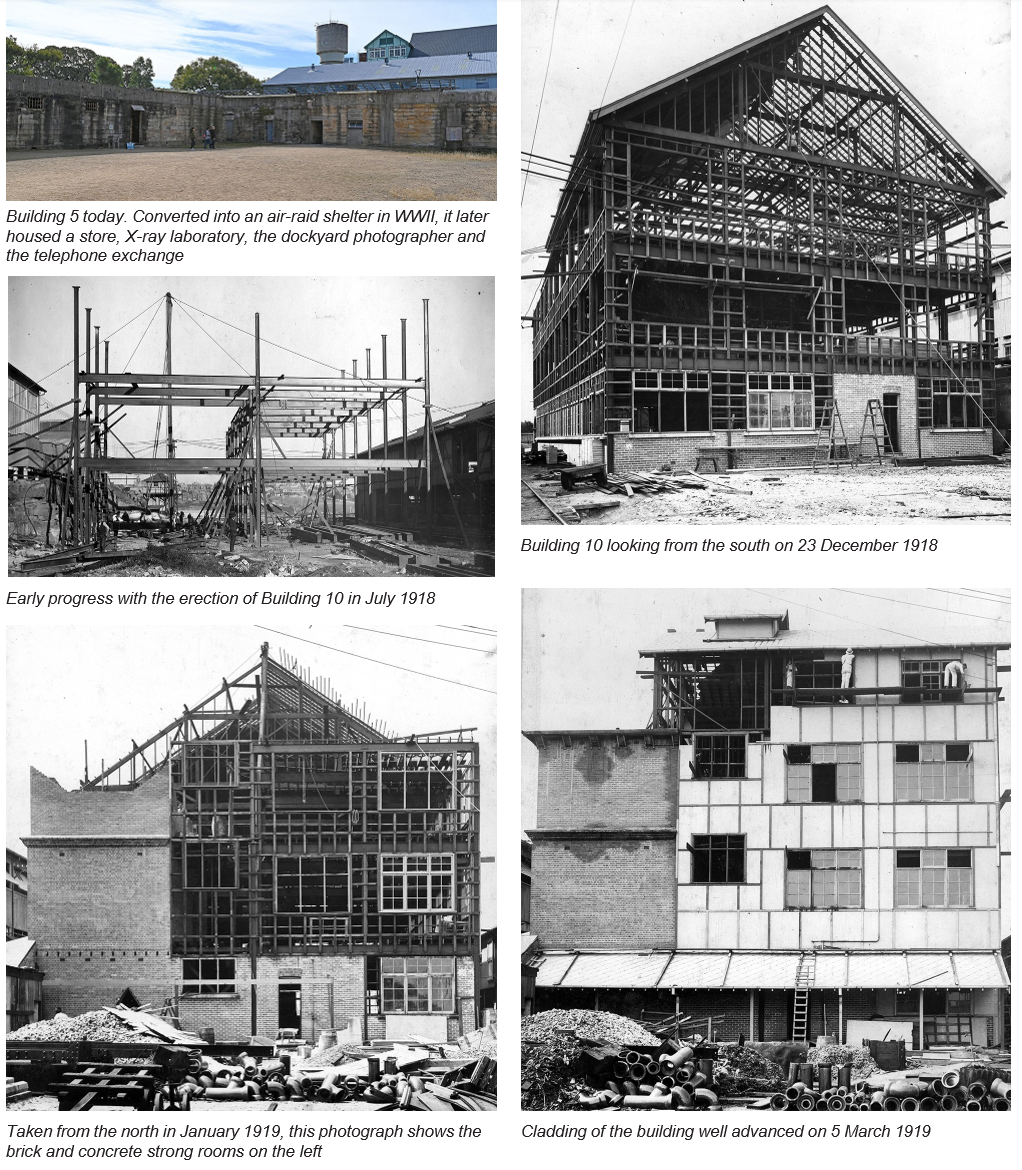

When the Commonwealth took over the island, the dockyard’s drawing offices occupied part of the convict-built prisoners’ barracks, Building 5. The buildings were too small and unsuitable for the dockyard’s growing needs. Plans for the development of the island, drawn up in 1915, included a new drawing office building on the site of the original convict quarry between the Mould Loft to the west and the Joiner’s Shop to the east. Construction of the three-level steel-framed timber building began in 1918 and it was completed around the end of 1919.

Building 10 (on the left) about 1920. The level 4 part of the building was the print room. The top of the strongrooms was a convenient location to set up frames to expose blueprints in natural light. Note that the wall of the adjacent Mould Loft (Building 6) has been painted white to reflect daylight into the drawing offices

The Ship Drawing Office on level 2 as completed. The half models on the wall in the background are of the cruiser HMAS Brisbane (on the left) and HMAS Adelaide. The drawing boards on trestles remained unchanged until the late 1960s/early 1970s when the boards were fitted with new steel-framed legs and under the board cupboards

As built, Building 10 housed the Electrical Drawing Office (EEDO) on the ground floor (level 1), the Ship Drawing Office (SDO) on level 2 and the Engine Drawing Office (EDO) on level 3. A smaller level 4 at the northern end of the building housed a Print Room. A three-level concrete and brick section at the north end of the building housed strong rooms for each of the drawing offices.

The early work carried out in the building included working drawings for the cruiser HMAS Adelaide and the design and preparation of working drawings for the 12,800 tons deadweight refrigerated cargo ships Fordsdale and Ferndale, the largest ships to be built in Australia for Prime Minister W.

- Hughes’ Commonwealth Line of Steamers which had been established in 1916. With the end of the ‘war to end all wars’, the workload of Cockatoo Dockyard declined during the 1920s, with the biggest shipbuilding task being the construction of Australia’s first aircraft carrier, the seaplane- carrier HMAS Albatross which was completed in December 1928.

The following year was to see a change for Building 10 — to play a major role in the embryonic Australian aircraft industry. In 1924 the young Royal Australian Air Force had established the RAAF Experimental Station at Randwick in Sydney. Under the command of Wing Commander L. J. Wackett, the Station designed and built a single-engine flying boat and repaired aircraft and engines. In 1929, with a need to save money an under some pressure from the British aircraft industry, the government closed the Experimental Station. Wackett resigned from the RAAF, but with the support of the Chief of Air Staff and his friend, the manager of Cockatoo Dockyard, Jack Payne, he moved with the best of the staff from Randwick to Cockatoo Island. The Aircraft Department was established in Building 10, with the displaced dockyard drawing offices relocated once more to the convict-built prison buildings.

Over the following five years, the Aircraft Department carried out repairs to civil and military aircraft, built a new wing for Sir Charles Kingsford Smith’s famous Fokker monoplane Southern Cross, and designed and built a six passenger twin-engine monoplane aircraft for Kingsford Smith. The aircraft was completed in mid-1933 and was named Codock after its birth place. It was not a success but the design was later developed into the very-successful Gannet.

A Supermarine Seagull III seaplane from HMAS Albatross after overhaul by the Aircraft Department

Building a new wing for Kingsford Smith’s Southern Cross in what had been the Electrical Drawing Office

Wackett was also interested in high-speed racing boats and he built at Cockatoo Island two stepped hydroplanes, Century Tire II and Cettein which were powered by aircraft engines and had a speed approaching 70 knots. The foray into boatbuilding resulted in a claim by the dockyard’s shipwrights for the aircraft work and the company which leased and ran the dockyard after 1933 closed the Aircraft Department in 1934. Wackett, later Sir Lawrence, went on to lead the Commonwealth Aircraft Corporation which, by 1949, had built 1380 aircraft and 1610 engines for the RAAF.

Building 10 became the drawing offices again, ready for the great expansion of the workload as World War II approached. Naval work dominated the tasks undertaken, with the construction of the Tribal-class destroyers and the detailed design and preparation of working drawings for the class of 60 Australian minesweepers of the Bathurst class. Eight were built at Cockatoo Island and the remainder by a revitalised industry throughout Australia with drawings and other assistance provided by Cockatoo Dockyard. Cockatoo Dockyard also built steam turbines, reciprocating engines and boilers for ships built at the dockyard and other Australian shipbuilders.

The twin-engine monoplane passenger aircraft Codock during trials at Mascot

Built by the Aircraft Department, the hydroplane Century Tire about to be lowered over the cliff on the way to the water

As had occurred during World War I, the Commonwealth Government began a merchant shipbuilding program under the supervision of the Australian Shipbuilding Board (ASB) which had been established in 1941. Five classes of ship were planned, the A, B, C, D and E classes. The A-class cargo steamers were based on a British design, but the design was developed at Cockatoo Island for the ASB and two ships, River Clarence and River Hunter, were built by Cockatoo. The B, C and D-classes were designed at Cockatoo Island for construction by other Australian shipbuilders.

The Engine Drawing Office and the Ship Drawing Office (on the other side of the columns) shortly after World War II. Little had changed in the 25 years since the building was completed except for improved lighting and a sprinkler system

In addition to the new-construction workload, the drawing offices had much work on ship repairs and conversions throughout the war years. After the war the workload did not diminish, with restoration of the passenger ships Manoora and Kanimbla for commercial service, the conversion of Q-class destroyers Queenborough and Quiberon into Type 15 anti-submarine frigates and the construction programs at Cockatoo and Williamstown in Victoria for the Battle-class destroyers Tobruk and Anzac, the Daring-class destroyers Voyager, Vampire, Vendetta and Waterhen (cancelled in 1954) and the Type 12 frigates. This continuous workload stretched into the 1970s and included the detailed design of the destroyer tender HMAS Stalwart, the detailed design of the planned Fast Combat Support Ship HMAS Protector (cancelled in 1973) and many other projects.

The Engine Drawing Office in the 1960s. Little had changed except for some more lights and lockers for the staff

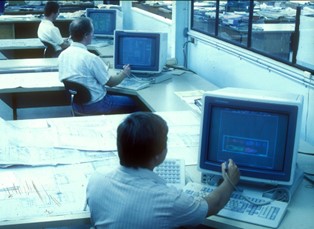

The advent of computers in the 1970s and 1980s made the big- gest change to the drawing offices in decades

Throughout this period Building 10 did not change much until the late 1960s. By then, the ground floor was occupied by the Electrical Drawing Office, the Supply Department and the offices for the Principal Naval Representative and his staff. Level 2 was occupied by the Ship Drawing Office, the SDO Design Office and the Engine Drawing Office. Level 3 housed a relocated Print Room, the Planning Office, Estimating Office and the Technical Library. There was little room to spare.

The dockyard involvement with submarines began in the 1960s with the refits of the Royal Navy T-class submarines based in Sydney as preparation for the support of the RAN’s own Oberon-class submarines from the late 1960s. At the end of the 1970s the contract for the construction of HMAS Success required an expansion of the drawing office staff and there was a need to improve the very basic amenities in Building 10, which had hardly changed in 60 years. The Supply Department was relocated to the top floor of the nearby old electrical workshop (Building 15) and a Submarine Technical Office was also set up in that building. Amenities were expanded by the addition of a prefabricated building accessible from the first floor level for use as a dining room with three prefabricated units at ground level to provide locker and change room space.

Building 10 always lacked adequate amenities for the drawing office staff. The 1965 Christmas party was held in the SDO strong- room

This 1986 photograph shows the prefabricated amenities buildings attached to the north face of Building 10

Following the government decision to close the dockyard by the end of 1992 activity in Building 10 gradually declined. During the last two years, the dockyard was largely stripped of machinery and equipment and a number of buildings were demolished for scrap. Building 10 survived. The contents of the drawing office strong rooms and other related storage were archived by the National Archives of Australia resulting in a remarkable record of the work of the dockyard. The contents of the archive provide a glimpse of the variety of the work undertaken in Building 10.

The people who worked in Building 10 made a major contribution to the work of the dockyard and the maritime industry of Australia. Others, trained in the building, went on to make their mark in other places. Well-known engineers and naval architects included John Wilson, James Morton, David Mitchell, David Carment, Noel Self, George Short, Harry Carder, Claude Barker, Cecil Boden, Laurie Harrison, Jim Campbell, Keith Lawson and Noel Riley. Those trained in Building 10 included well- known naval architects and yacht designers Alan Payne and Warwick Hood.

Apart from occasional special events, Building 10 has remained vacant for three decades. Recently the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust has had the old asbestos-cement cladding on three faces of the building removed and replaced with modern materials. Great care has been taken to reproduce the original appearance of the building and the result is spectacularly successful. The fourth, southern face of the building awaits restoration when finances permit. It was reclad with steel around 1970 when the concrete lift tower which gives access to the building from the tunnel beneath was built.

Cockatoo Island presents many challenges for its custodians. Not least is finding new uses for the island’s buildings which respect the remarkable history of the island but provide much-needed income for the Trust. The Drawing Office building awaits a new role for its second century.

Building 10 actually moves slightly in strong winds. On a quiet night it creaks eerily when buffeted by a strong southerly — or perhaps the building is trying to remind us of the contribution made by those who worked in it over seven decades to the naval, marine, aviation and general engineering development of Australia.

The beautifully restored northern and western facades of Building 10 in 2023.

The walkway between the Ship Drawing Office on level 2 and the Mould Loft was added when the tenth-scale loft was built in 1970