John Jeremy

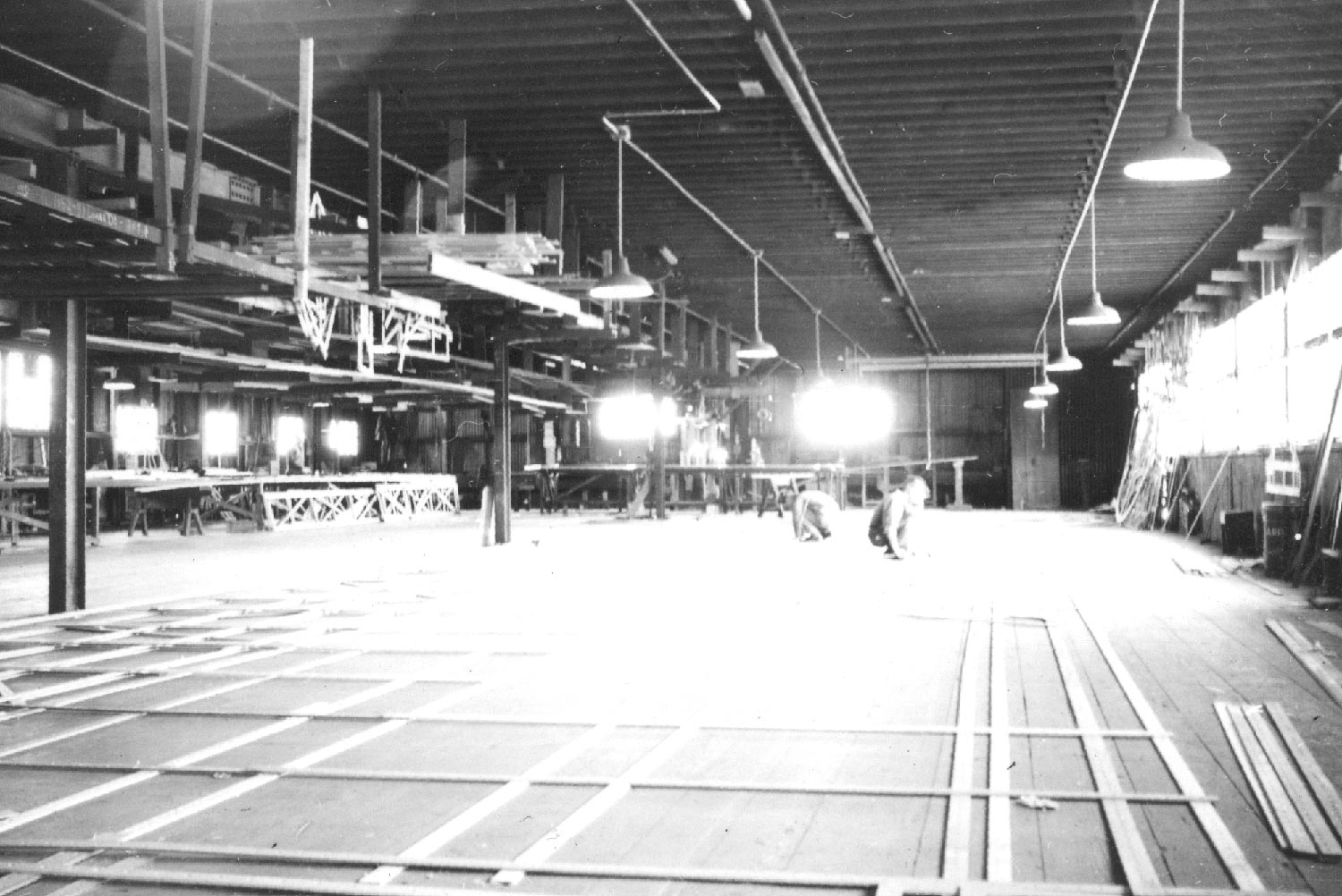

Occasional Paper 165 told the story of the three-storey green building on the top of Cockatoo Island in Sydney, Building 10 — the Drawing Office building — and outlined the building’s role in the development of the Royal Australian Navy and in the maintenance and repair of many ships, naval and commercial, in peace and war. Building 10 stands amongst several other grey-painted buildings, the purpose of which would not be obvious to the casual observer. Immediately to the west of Building 10 stands a two-storey timber and steel-framed structure clad in corrugated steel sheeting. The steel framing comprises riveted ‘Cargo Fleet’ RSJs and simple bolted Fink trusses and the building has solid timber floors lit by predominantly multi-paned casement windows — a form of construction making possible large open spaces. This is Building 6, the dockyard’s Mould Loft, and its heritage value has been assessed as ‘Exceptional’. [1]

Cockatoo Island is the largest island in Sydney Harbour. Its first use after European settlement was as convict prison. The prison role began in 1839 and continued in several forms until the completion of Long Bay Gaol in 1908 when the final prisoners were removed from Cockatoo Island.

The island’s convicts built the now World Heritage listed Fitzroy Dock which was completed in 1857, when ship repair began on the island. Shipbuilding began in 1870 when the island industrial activities became the responsibility of the Harbours and Rivers Branch of the NSW Public Works Department. In 1912 the island was purchased by the Commonwealth from the NSW government and it became the Commonwealth Naval Dockyard — the first naval dockyard of the Royal Australian Navy.

After Federation in 1901, in 1904 the NSW government began a modernisation program of the dockyard’s facilities, and further work was begun after 1908. This work included the construction of new shipbuilding facilities on reclaimed land south of the Fitzroy Dock, which comprised two shipbuilding slipways provided with cantilever cranes and steel working machinery, much of which was made on the island. This work was completed by 1910.[2]

After 1904 the Government Dockyard built a number of vessels including dredgers, hopper barges and tugs and looked to a future which would include construction of ships for the Commonwealth Naval Forces, which became the Royal Australian Navy in 1911. The island dockyard subsequently assembled the destroyer Warrego, which had been prefabricated in Scotland and shipped to Australia for completion. In August 1912 the dockyard entered into a contract with the Commonwealth to build three more destroyers and a cruiser for the RAN which became HMA Ships Huon, Torrens, Swan and Brisbane — the start of 75 years of shipbuilding for the RAN on Cockatoo Island. In preparation for this increased shipbuilding activity, the NSW government further improved the shipbuilding facilities by the construction of a new mould loft — the first dockyard building to be constructed on the upper level of the island — Building 6.

The mould loft plays an essential part in the shipbuilding process. Whilst the shape of a ship is defined by her designers in lines and body plans, these are drawn at small scale but, whilst offsets lifted from these plans may be adequate for the development of further drawings, they are likely to be insufficiently fair for use at full size. The task of fairing the ship’s lines and producing the necessary full-size information for the construction of the many parts of the ship’s structure is that of the shipwright loftsmen in the mould loft.

From the faired lines of the ship, wooden templates, or moulds, could be made to define the shape of all the various parts of the frames, shell, decks and bulkheads which could be used to mark the steel plates for cutting and shaping. For parts of the ship with complex shape (like a shaft bossing for example) the loft might make three-dimensional moulds at full size which the plate shop could use for forming the plates by pressing or heating.

For many years ship’s frames were shaped by heating to a red heat in furnaces and bending on steel slabs in the shipyard. To check the shape of the frames a scrieve board, a large wooden floor, was located next to the bending slabs where the frame lines of the ship were transferred using the ‘As Lifted’ offsets. The use of the scrieve board reduced the number of wooden moulds required. At Cockatoo Island the use of furnaces for the shaping of frames and sections continued until replaced by a cold frame bending machine in the early 1960s. The furnaces, bending machine and scrieve board on Cockatoo Island were located in Building 40, constructed in 1912 near the head of No. 1 shipbuilding slipway. Building 40 no longer exists but two small cranes and some parts of the bending slab provide a reminder of its past.

An important task for the mould loft was to make a half-block model of the hull of the ship. The model was usually made of solid wood, at a scale of around 1:48, depending on the size of the ship. The model was used by the ship drawing office to arrange the seams and butts of the shell plating to ensure fair plate lines and to provide information to assist ordering steel plate to minimise wastage. The plate lines so developed were transferred to the shell expansion plan and the plate line body plan. The plate lines were also transferred to the body plan on the loft floor. A large number of half models of ships built on Cockatoo Island survive in the custody of the Naval Heritage Collection.

The last large ship to be lofted at full size was the destroyer escort HMAS Torrens, built between 1964 and 1971. By the 1960s lofting methods were changing. The development of stable Mylar drafting films and flame cutting machines capable of being controlled by photo-cells tracing accurate drawings resulted in tenth-scale lofting being widely adopted. At Cockatoo Island, plans for the modernisation of the shipyard, developed in the 1960s, included an air-conditioned tenth-scale mould loft on the top floor of Building 6 to provide tenth-scale drawings for use on a Logatome flame cutting machine in the plate shop. Whilst the full modernisation of the shipyard was never carried out, tenth-scale lofting was adopted for the proposed fast combat support ship, to have been HMAS Protector. By the time that project was cancelled in 1973, structural drawings were complete and lofting work was well advanced. With the advent of computers, the fairing of ship’s lines by computer was being adopted and, for Protector, the computerised lofting was undertaken by the Danish Ship Research Institute. The process was far from fully developed and many inaccuracies had to be resolved traditionally in the tenth-scale loft at Cockatoo Island. For the last ship built at Cockatoo Island, HMAS Success, the loft work and preparation of computer numerical control tapes to drive the Logatome flame cutting machine (converted to CNC) was carried out overseas by Shipping Research Services AS (SRS), Oslo, Norway.

Despite the introduction of computerised lofting, full scale moulds were necessary at times for complex shapes (like the bulbous bow of Success, for example) and as templates for shaping hull plates, ensuring the survival of traditional lofting techniques.

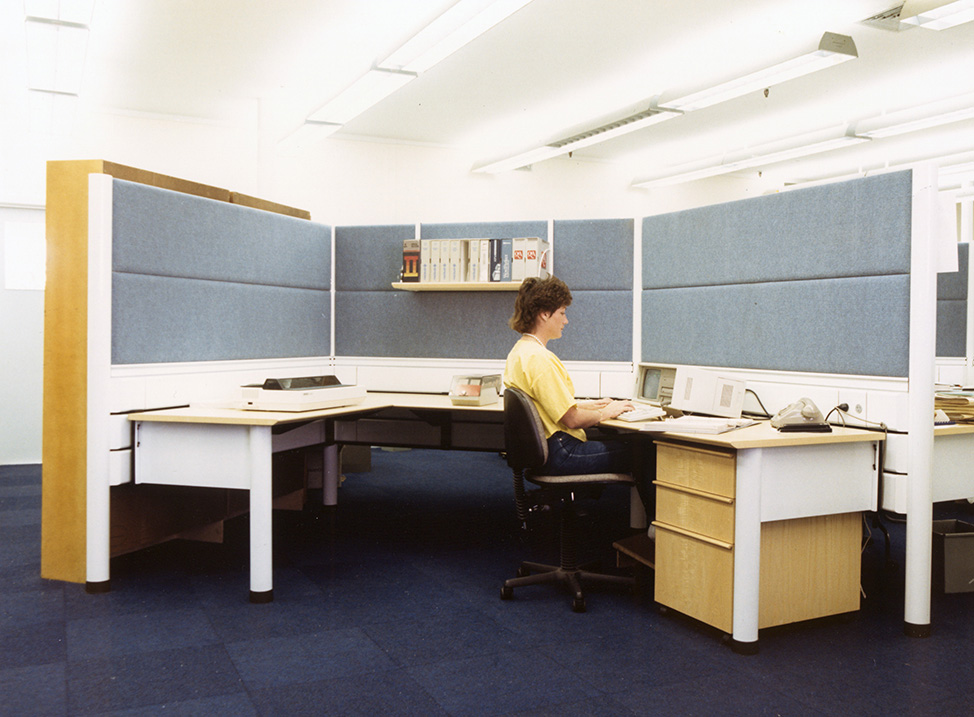

in the early 1980s

With the change in lofting practices it was, perhaps, natural that space in Building 6 would be used for other purposes. In the 1980s offices for the Quality Control Department were built at the southern end of the ground floor. Also in the 1980s tenth-scale loft was used for an Integrated Logistic Support (ILS) Department engaged in the production of handbooks and training videos for HMAS Success. With the decision by government to close Cockatoo Dockyard by the end of 1992, the last users of the tenth-scale loft space were the team from the National Archives of Australia engaged in the task of archiving the very large collection of dockyard records dating back to the mid-19th century.

Cockatoo Island, now a World Heritage Site, is in the custody of the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust. Over the years the Trust has completed maintenance and conservation work on Building 6 which is probably the only surviving full-scale mould loft in Australia. The top floor, which retains a priceless record of the shipbuilding work of the dockyard, was cleaned in 2007 and fully photographed before being covered by protective carpet tiles.

between 1911 and the mid 1960s in the lines of ships built there inscribed into the timbers of the top floor

which were completed in 1841

The building was always subject to extremes of temperature — freezing cold in winter and very hot in summer. The roof is now insulated.

Since the Trust took responsibility for Cockatoo Island, Building 6 has been used as a function space or for exhibitions, such as during the Sydney Biennale. The Draft Master Plan for Cockatoo Island, published in November 2023, proposes that Building 6 be used ‘for public programs, enhanced with visual displays on the convict system, industrial and reform schools, including peoples stories of resilience, escape and rebellion.’ Given the location of Building 6, such use is not inappropriate, but it is to be hoped that space will also be found to display and interpret the industrial history of the building which played such a large part in shipbuilding for the RAN and other customers over some 80 years.

References

1. Cockatoo Island Dockyard — Conservation Management Plan (2007), Godden Mackay Logan for the Sydney Harbour Federation Trust.

2. Jeremy, J C, Cockatoo Island: Sydney’s Historic Dockyard (1998 and 2005), UNSW Press, Sydney.

3. Newton, R N, Practical Construction of Warships (1955), Longmans, Green and Co., London.

4. Attwood, E L, and Cooper, L C G, A Text Book of Laying Off or the Geometry of Shipbuilding (1914), Longmans Green and Co., London.