By CDRE Richard T. Menhinick, AM, CSC, RAN (Retd)

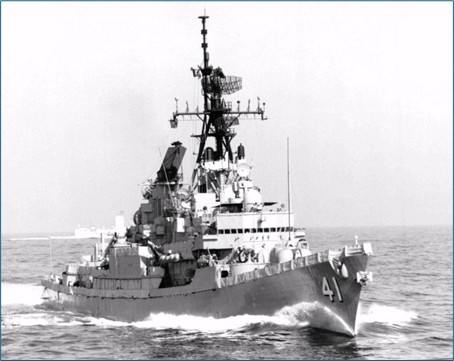

The Naval Historical Society is grateful to Commodore Menhinick for allowing publication of this, his 2025 Anzac Day address to the Pioneers Club of Australia. During the First Gulf War, as a lieutenant commander, he served as a warfare officer in the guided missile destroyer HMAS Brisbane. Given its highly capable air defence systems Brisbane was assigned to forward patrol locations in the northern Persian Gulf.

It is now some 34 years since we fought the First Gulf War. I joined the Navy in 1976 at the old age of 16, and that was just over 30 years after the end of the Second World War. So, the reality is that the Gulf War is longer ago now than WW II was when I joined.

A pertinent question is whether the lessons and reflections on the Gulf War, especially the maritime side of it, are still relevant to us today? I think so, and hopefully I can address this as I think it is a conflict which is quite often overlookedbut one which in fact had many lessons which are still prescient for us.

I was the Direction Officer, which is the air warfare and combat systems officer, in the guided missile destroyer HMAS Brisbane under the command of Chris Ritchie, so it is Brisbane centric somewhat.

Iraq invaded Kuwait on 1st August 1990. After condemning the Iraqi invasion and demanding Iraq’s withdrawal the UN Security Council decided to impose economic sanctions against Iraq and occupied Kuwait. The Security Council also authorized states with maritime forces in the area to “use such measures as may be necessary” to ensure strict implementation of the sanctions, as related to shipping and trade, especially potential armaments into Iraq and Iraqi fuel exports, on which their economy depended.

On 10th August 1990, the Hawke Government announced cabinet’s decision to commit Australia. Australia would deploy naval ships in support of the blockade and later a small number of intelligence and medical personnel in support of UN Security Council Resolution (UNSCR) 660 on Operation Damask 1. That date marks the beginning of virtually 31 years of connected warlike operations for the ADF in the Middle East Area of Operations. To assist in this, HMA Ships Success, Adelaideand Darwin were deployed basically over a weekend, and they sailed from Sydney on 13th August 1990.

The commanders, officers and sailors in the ships deployed in Damask One and Two were a veritable who’s who of majorcharacters and distinguished leaders in our Navy of the last 30 years including two future Chiefs of Navy and a raft of future star ranked officers and officers and sailors whose experiences in this conflict would shape the navy for years to come.

It is true to say that Operation Damask and the Gulf War was key for our Navy for years afterwards. It would also be remiss ofme not to mention the late, great Ted Walsh. Ted was the chief damage control trainer at Fleet. Using his experiences from the Royal Navy and the Falklands War just 8 years earlier he really made sure we were well prepared should the worse have happened, and on this Anzac Day event, we thank him and remember him especially for this.

As a hot war became more likely, Brisbane in company with HMAS Sydney commenced deployment to Operation Damask on 12 November 1990 after an extensive enhancement package. Fitted were; Rigid Hull Inflatable Boats, two xPhalanx Close in Weapons Systems and magazines and some 700 Radar Absorbent Material (RAM) panels with great assistance from the then Defence Science and Technology Organisation. Electro-Optical infra- red surveillance deviceswere also fitted in about 6 weeks and then we did a workup off the coast of Sydney which continued during the passagearound the bottom of Australia and past Diego Garcia enroute to the Persian Gulf.

The ships entered the area of operations in the Gulf of Oman on 3 December 1990 in company with Success who had remained from the first deployment of Darwin and Adelaide. In fact, there is a famous photo of all five Australian ships in the Gulf of Oman as we handed over.

We entered the Persian Gulf itself on 16th December, passing through the Strait of Hormuz. The extra weapons, sensors and RAM panels made us very aware of the infra – red missile threat, so we also had fire hoses laid and punctured so thatsea water cooled the hull in the vicinity of the fire rooms where our 1250psi boilers were. This worked a treat and completely changed the heat signature of Brisbane so that any infra-red missile that got though wouldn’t impact the hull and fire rooms, but the stacks – which we thought was a lesser danger, perhaps a lesser of two weevils! (to paraphrase Russell Crowe in Master and Commander).

We were the first Australian ships to actually enter the Persian Gulf in this operation. We conducted operations from then on as part of Battle Force Zulu or Persian Gulf Battle Force. The Americans call it the Arabian Gulf, so everything was the Northern Arabian Gulf Battle Force. A bit like they now call the Gulf of Mexico the Gulf of America, I think theythought the Persian Gulf was a little too Iranian sounding after 1979 for their liking. So, there is some history andprecedent for them just changing names as they wish.

Within the Persian Gulf, well before the war itself, our battle force was tasked to conduct sea superiority, counter-air, maritime interception and offensive strike operations. Supporting naval operations provided protection of sea lines of communications, amphibious operations, maritime support operations – including mining, explosive ordnance destructionand logistics. I will concentrate on Air Warfare, as that became our primary focus in the period we were in the Persian Gulf.

Air Warfare Objectives were many but included:

- Providing a layered defence to protect the Carrier Task Force,

- maintaining a continuous 24-hour combat air patrol or fighter coverage, in the Northern Persian Gulf,

- providing air warfare protection for amphibious ready groups and

- providing defence in depth against threats originating in, or transiting through Iran, yes Iran – some things never change.

The potential threat from Iran was treated very seriously and was exacerbated by the mountains which created extensiveradar shadow zones on the eastern shore of the Gulf. These could effectively shield Iraqi and Iranian aircraftapproaching the force from shipborne radars until ‘feet wet’. The Zagros Mountains on the west coast of Iran in particular were a concern and a dedicated air warfare escort was stationed specifically to guard against this threat.

Often this was Brisbane, due to the superiority of our 3-dimensional SPS 52C air search radar. Further to this, extensive use was made of airborne early warning aircraft, predominantly carrier borne and land based E2C Hawkeye aircraft.These were tasked to patrol the eastern edge of the Gulf constantly. USAF and Saudi Air Force E3 AWACs also conducted24-hour operations over Saudi Arabia monitoring the northern and western threat sector.

Joint combined operations with multi-national naval forces required a high degree of air deconfliction and co-ordination.That this was achieved can be ascertained from the fact that throughout the operation over 14,000 sorties were flown by carrier borne aircraft without a single blue-on-blue engagement. That is a pretty remarkable statistic.

To address the issues of bringing NATO and Pacific based forces together, which in those days operated to different tactical data link standards, the division of responsibility was stipulated geographically. The US Air Force and MarineCorps had responsibility for what was known as the Western Sector. This was basically Saudi Arabia and the Gulf Statesout to 12nm from shore. The rest of the airspace above the Persian Gulf eastwards was known as the Eastern sector and was the responsibility of the maritime forces.

The Threat

The Iraqi forces had the capability to inflict a large pre-emptive strike against coalition naval forces.

The Iraqi air force comprised 1315 aircraft at the time of the invasion of Kuwait. Of these some 817 were fighters/fighterbombers and 14 dedicated bombers. Many of these were obsolete, however modern technologically capable aircraft included 83 Mirage F1 EQ5/EQ6 variants with Exocet missiles, 41 MIG 29 Fulcrums, 33 MIG 25 Foxbats, 23 SU24Fencers and Puma helicopters with Exocets as well. This order of battle, when coupled to the uncertainty of Iranian reaction to Allied actions and the proximity of friendly forces to potentially hostile land masses, formed the basis of the air warfare organisation.

Indeed, some of the more nervous moments were before hostilities in December 1990 and early January 1991, when together with the US Cruiser, Bunker Hill, we were up as close as60nm south of Iraq and they were flying Mirage F1s down and going feet wet directly towards us on Exocet firing profiles, luckily without launching as that was when the forces at seawere not that strong.

Then there was the Iraqi floating and bottom-laid mine threat.

ALLIED Forces

As January unfolded and the UN deadline for Iraq to withdraw from Kuwait approached, we really started to beef up the maritime air presence and from then on Allied forces had a technological and numerical advantage over Iraq. Prior to 11 January 1991 the first carrier to arrive, USS Midway had conducted operations predominantly in the Gulf of Oman. In late 1990 she operated twice in the SouthernPersian Gulf for periods of about one week. Then other Carriers arrived and moved into the Gulf permanently.

First, it was USS Midway Battle Group on the 11 January, just 6 days before hostilities. Then 5 days later, it was the USSRanger Battle Group and two carrier operations commenced.

On 17 January 1991, the US pre-emptive strike signaled the commencement of Operation Desert Storm. 400 plus tomahawk missiles were launched from US ships surrounding Brisbane – quite a site from our upper decks I was told. That is when I learnt what outgoing friendly missile symbology was for and what the code word “Happy Trails” and “Free Riders Away” meant! I was on watch in the Operations Room, and we went to action stations in the very early hours and awaited an Iraqi response – none came that day.

Just three days after this the USS Theodore Roosevelt Battlegroup arrived in the Gulf and three carrier operations commenced. Finally, on 15 February, the USS America Battlegroup moved from the Red Sea to the Gulf and four carrier operations commenced leaving the carriers USS Saratoga and USS John F Kennedy in the Red Sea.

Multi-national forces operating in support of UN resolutions had varied taskings stipulated by national directives. These precluded the employment by the US Navy of some units for integrated air warfare due to varied national Rules of Engagement, which were key determinants in who was where and who could do what, as was English language issues. Naval forces included units from France, Netherlands, Spain, Belgium, Denmark, Norway, Italy and Argentina.

Naval units from Australia, Britain, US and Canada, (the four eyes) were predominantly in the northern Persian Gulf. Naval forces from Western Europe predominantly patrolled the southern Persian Gulf and had little input into the air warfare posture. This yet again highlights the need for constant interoperability, combined training, exchange postings and compatible systems between close allies and partners.

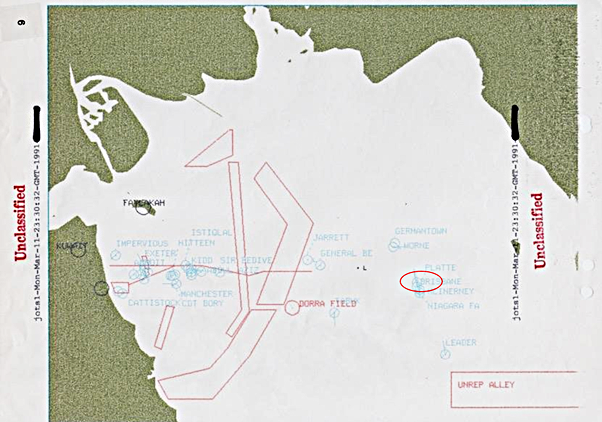

The carriers operated within areas that were approximately 60nm long and 20nm wide and were based on an axis of 3200 which was the prevailing wind direction. This area moved progressively up towards Iraq as hostilities progressed.

Operations

Three permanent Combat Air Patrol stations, where defensive fighters constantly patrolled, were established in December 1990 and this was expanded over time to eleven. These were supported by four tanker stations. Thesesustained extensive strike patterns which were being flown from the carriers. At the height of the offensive, five tankerswere airborne continuously to support major strike periods. The way the Americans did this was just really, really impressive. This has stood with me for the last 34 years. Wow, they know carrier operations and just how effective and versatile carrier-based air power is.

One big issue was the identification of civilian aircraft. If there was any doubt a challenge was issued and/or a visual IDconducted by our fighters. Warning procedures were initiated and a unit would conduct ‘tornado’ procedures. Again, we had no instance where civilian aircraft were engaged, obviously most stayed well clear in any case.

As can be expected in a hectic strike environment there were many occasions where aircraft identification was fraught. It had been repeatedly stressed that failure to abide by correct procedures would see the aircraft classified as a ‘Smoker’that is to quote the USN “a pilot who wishes to share his cockpit with an SM-2 block 2 missile”. Many friendly aircraft were locked up by fire control systems, many visual identifications and challenges carried out, but the aggressive attitudeof all units to ID and deconfliction proved effective and safe. Indeed, at one stage I was on watch in Brisbane and had an unidentified helicopter locked up for some minutes with a missile ready to be fired, coming from the rough direction of Iran before its ID as the British commander moving between his ships without filing a flight plan was established.

RAN Participation in Air Warfare

As for Brisbane and Sydney specifically, we were employed for the majority of the period as escorts for the carriers and were assigned in grid sectors. Due to the very real threat of drifting mines Brisbane would cruise up threat which wasessentially up current during daylight hours and then basically slowly move or drift down with the current at night. The Electro Optical system and a mine lookout would sweep for mines. Having 4 high pressure boilers focused our mind onthis. Replenishments at Sea of fuel and provisions occurred about every 4 days and those sometimes included importantly mail drops. Yes, it is 34 years ago so we all wrote letters and hungrily awaited them. We also became veryused to American Babe Ruth chocolate bars and Hershey bars in general.

Based on commonality of equipment and ease of RAN/USN integration, both RAN units maintained responsibility for the more crucial north/northwesterly screening sectors of the carrier operating area in the weeks leading up to, and throughout, the six weeks of hostilities. Assignment also included the sector known as the ‘Zagros Mountains Gate Guard’which saw ships specifically tasked to guard the radar shadow zone down to the Iranian coast. Both ships patrolled to within15nm of Iran while carrying out this duty which ensured a high degree of alertness, especially given the uncertaintyengendered by the migration of so many Iraqi aircraft into Iran in late January and early February. Other duties were carriershotgun, combat search and rescue duty in the Northern Persian Gulf for Sydney and northern Persian Gulf escort ofreplenishment vessels for Brisbane. As I mentioned earlier, the SPS 52C air search radar, the 3D air search radar in Brisbane with its many modes proved equivalent to the first generation SPY-1B radar in many cases and actually superiorin the littoral environment, which was another reason for Zagros Mountain employment.

IRAQI Attacks

Iraq made several attempts to attack the maritime force. There were some significant ships in the Gulf.

After 17 January 1991, Iraq made two attacks with Mirage F1 aircraft, but these were shot down by Allied fighters short ofExocet release range. Both attacks employed no deception attempts and only 4-5 aircraft – far too few to break through.One mass raid of 40 plus aircraft etc. could have had very different results. Other threats which we were on alert against was a chemical attack using SCUD missiles. SPS 52C radars actually tracked a number of SCUD missiles heading into Saudi Arabia. The Silkworm missile was also an issue. About 20 were fired, with one shot down by HMS Gloucester.Most missiles appeared to be defective. The Iraqi navy consisted of brown water units, supplemented by captured Kuwaiti patrol boats. In the early days of the war, they made only tentative forays and were subjected to air and surfaceattacks. They played no meaningful part in the conflict and were attacked, harassed and destroyed by allied forces withrelative impunity. Some 138 vessels of all types were sunk or rendered non – mission capable.

As mentioned earlier, mines were a significant threat. Iraq laid extensive minefields around Kuwait with some 2,000 mines laid. Many were also loose,being deliberately laid as free floating. These floated down the western side of the Gulf and up the east coast in an anticlockwise direction. Two US ships, Tripoli and Princeton were seriously damaged in February by mines. Brisbanehad three mines detected within about ½ nm from the ship.

Our ships spent about 55 days at sea non-stop in Defence Watches. Westralia replaced Success as theAussie ship in the Allied replenishment group midway through our deployment. For Brisbane this was 6-hour watches as the Stokers could onlyspend 4 hours in the fire rooms and then did the next 2 in damage control stations. I am pretty sure that 7s and 5 were used in Sydney but this could not work for Brisbane with our steam boilers and the heat in the fire rooms and engine spaces. This was draining especially given the fact that due to underwayreplenishment operations the time at sea was virtually unending within a high-risk environment.

We gave a situation report at every change of watch from the Operations Room and then we stayed quiet, so the off watch had a chance to sleep. Thus, those in damage control stations and machinery spaces had few if any updates for the six hours and I wonder now if that led to increased mental stress as this was unrelenting for eight weeks straight at one stage. We in the Operations Room had the full picture, the vast majority of the ship’s company, many below the waterline did not. Food for thought I reckon and something I have only really considered deeply as the years unfold. We were also injected with vaccinations for a range of things including anthraxand the plague and we took the nerve agent pre-treatment tablets and had atropine etc with us at all times. We did attempt to shut down Brisbane against any chemical attack, but we gave up as it just got so hot so quickly it was just not achievable! The visibility was sometimes awful as was air quality, due to sand and the toxic smoke from the oil fields that the Iraqis were burning.

Naval forces facilitated an immediate diplomatic and political response to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait by economic blockade, transported the vast majority of land forces and their equipment to the area of operations and then provided significant naval gunfire support and offensive strike via carrier borne aircraft and cruise missile attack against Iraqi military installations and positions.

At the height of the conflict six aircraft carriers, two battleships, 15 cruisers, 67 destroyers and frigates and over 100logistics, amphibious and smaller craft were involved. These forces were drawn from 15 nations and deployed more than 800 rotary and fixed wing aircraft.

Despite the threat of floating mines, Allied control of the sea was absolute, with the economic blockade being completely successful. In addition to the success of the strategic strike from the sea, the threat of amphibious attack caused consternation to the Iraqi command and resulted in significant Iraqi forces being retained in Kuwait itself, rather than being moved to face the Allied land offensive when it began.

After Operation Desert Storm was completed and Kuwait was liberated and hostilities ceased on 28th February 1991, we remained off Kuwait, in the smoke from the oil fires for another 6 weeks or so, as mines were cleared and humanitarianrelief efforts commenced, and the ceasefire was enforced.

The Gulf War was an excellent example of the contribution that maritime units and maritime power can make. The roles and tasks of maritime surveillance, maritime patrol and response, protection of offshore territories and resources,intelligence collection and evaluation, protection of shipping, strategic strike and operations in support of land forces were all executed by the Allied navies in the Persian Gulf.

To conclude, this was a multi-faceted hot war with air, sea and a mining threat. It demonstrated the importance of having meaningful three-dimensional air warfare capability, something we gave away almost immediately afterwards as the 90-s progressed and the DDGs were not replaced, leading to a 20-year gap. It also demonstrated the role of organic sea-based air projecting over land.

After the Gulf War the RAN had a virtually continuous presence in and around the Gulf for 30 years and just about everyone who has served has done multiple deployments there. Our ships company was superb, and it was an honourto serve with them in Brisbane.

In a world which is increasingly unstable and uncertain the complexity and nature of what we did some 34 years ago andhow important maritime power projection is, should be remembered.