On Thursday 9th August 2018 the ABC 7.30 Report broadcast a story by Tracy Bowden about the first use of penicillin in Australia. Tracy has given permission to the Naval Historical Society of Australia (NHSA) to publish this interesting and historical Report in full due to its Naval connection. This paper also includes some further research undertaken by both the NHSA and Westmead Children’s Hospital Heritage Committee.

Peter Harrison, far right, with his mother and siblings, in the mid-1940s after being treated with penicillin. Image supplied by Harrison family

A secret mission to save a young boy’s life — which has only just come to light — has re-written the history of penicillin and antibiotic use in Australia.

The man behind the story is Peter Harrison, who has just celebrated his 82nd birthday. If Mr Harrison had not received the “wonder drug” 75 years ago, it is likely he and his children would not be here today. “I’m overcome with joy to be part, a small part, of the beginning of the penicillin story,” Mr Harrison told 7.30.

Peter Harrison, Australia’s first penicillin recipient, is now a healthy 82-year-old.

Image supplied by ABC News: Alex McDonald

Back in 1943, Mr Harrison suddenly became ill and was admitted to Royal Alexandra Hospital for Children at Camperdown, in Sydney. He was diagnosed with Pneumococcal meningitis.

“I was terrified,” he said. “I wondered what was going to happen. I thought, maybe I will die here.”

His father, Dr Leo Harrison, was a Navy surgeon. With no modern antibiotics, treatment options were limited. As his son got worse, Dr Harrison was convinced the only answer was penicillin, a drug which was, officially at least, not yet available in Australia.

What happened next was uncovered just a few months ago, when researcher Beth Robinson was sorting through old hospital documents now stored at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead.

The original note and envelope recording Peter Harrison as ‘The first child in Australia to have penicillin’. (Supplied: The Children’s Hospital at Westmead)

“On the front of [one] envelope was a handwritten line saying, ‘The first child to receive penicillin treatment in Australia,'” Ms Robinson said.

“There had been no evidence of this story anywhere, it just didn’t exist. It predated anything else the records had shown so far.”

‘He would not be alive today’

A team at the hospital continued to dig and the story that emerged was remarkable.

At the time, penicillin was an experimental drug. It was being produced in the United States, with precious supplies mostly reserved for the military. Australian doctors by-passed official channels, asking their counterparts in America to supply the drug to a small boy in Sydney — Peter Harrison.

“The request was granted and the turnaround time was extraordinarily quick,” Dr Alyson Kakakios, from The Children’s Hospital at Westmead, said. “It was sent on Saturday the 10th of July, and by the following Thursday it had actually arrived in Australia. “He would not be alive today if he had not received that penicillin.”

Beth Robinson with the documents she found inside a safe at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead archives. (ABC News: Alex McDonald)

At that time, the war in the Pacific was at its height. The precious cargo was sent on a Liberator bomber and the Australian doctors were urged to keep the one-off delivery secret.

“When you think of what would have been on those planes — aircraft parts, troops — they were also carrying a small box with penicillin in it on dry ice,” said Dr Glen Farrow, who was also on the hospital committee investigating the case. “Someone had to keep topping up that dry ice all the way. So there were a lot of people keeping the penicillin cold and making sure it got to Peter safely.”

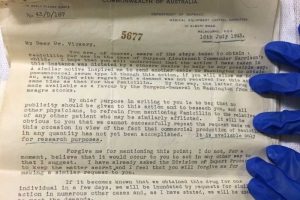

The letter telling the doctor who administered the penicillin not to tell anyone. (Supplied: The Children’s Hospital at Westmead)

‘Boggles my mind’

The researchers discovered the boy at the centre of the story had not only survived but was still alive and well.

Mr Harrison’s daughter, Susan Field, said the story was “amazing”. “My dad’s life was saved as a child. If it hadn’t been, I wouldn’t be here,” Ms Field told 7.30. “As children we had this in our family folklore, that Dad’s life was saved by the US military bringing the penicillin out, but we didn’t have a lot of facts.”

His son, Peter Harrison Jr, said: “They were just experimenting, and it worked because it was the wonder drug.”

Peter Harrison’s father, Dr Leo Harrison. (Supplied: Harrison family)

Mr Harrison does not remember much about what happened, but he recalls the US pilot coming to his hospital bed to wish him well.

Tilly Boleyn, curator at the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences, said this new information changes the official records in terms of Australians being treated with penicillin.

“The first treatment I know of was an Australian soldier in New Guinea. But that would have been in December ’43. And in fact, Australia only started thinking about and investigating how we would make penicillin in October, so [Mr Harrison was] well before that.”

Another Australian, Sir Howard Florey, played a key role in the development of penicillin, recognising its potential to kill the bacteria that cause infection.

Mr Harrison recently met those who have been helping solve the mystery. It would not have happened without the help of Americans, and the acting US consul general based in Sydney, Linda Daetwyler, was keen to meet Mr Harrison and hear more about his story.

“It boggles my mind how that happened,” Ms Daetwyler said.

“I don’t think it would happen nowadays, with all the bureaucracy we have, but clearly there were a lot of people along the line that were touched by this little boy’s story and pushed away protocols and regulations to make a miracle happen.”

Mr Harrison and the researchers still wonder what contacts or connections his father had to make the delivery possible.

“He pulled some strings and I don’t know how he did it, but he was a determined man, like I am,” Mr Harrison said.

Further Research by the NHSA and The Children’s Hospital at Westmead Heritage Committee

The NHS examined Surgeon LEUT Harrison’s Service Record and established that he spent most of his time in the service ashore, serving briefly in HMA Ships Parramatta and Manoora. Following time at HMAS Penguin, the Naval Hospital at Balmoral, in January 1943 he was posted to HMAS Kuttabul. Intriguingly, little over a month after obtaining the penicillin that saved his son’s life in the July, he was approved for discharge from the RAN by the Central Medical Co-ordinating Committee on 23rd August 1943; the Committee also recommending he be promoted to Surgeon LCDR. We wondered if the two events were connected and that his sudden discharge at a time when a Navy at war would have been desperate to retain as many medical practitioners as possible was some form of sanction.

Further research has shown this not to be the case; his engagement had expired, and it appears that Harrison retired to General Practice and raising his family.

At the same time, contact was made with The Children’s Hospital at Westmead Heritage Committee. With the assistance of a Master of Museum and Heritage student from the University of Sydney, Beth Robinson, and Director of Clinical Governance Dr Glen Farrow, who has taken a particular interest in this story, the Committee has been attempting to establish just who LCDR Harrison contacted to arrange for the supply of the medicine.

In this desperate situation it would not be unusual for Harrison to be talking to other naval doctors based in Sydney or even seeking help through the Navy chain of command. While we cannot prove what happened, the facts as we know them suggest that this is what he did. In Melbourne at the time a Dr Wilberforce (Bill) Newton was a physician at the Alfred Hospital, a consultant physician to the Navy and an expert in chest disease and TB. He would have been up to date in advances in antibiotic therapies, including the development of penicillin in the US, and would be the obvious expert to consult within the Navy.

Bill Newton was also the younger brother of Sir Alan Newton, renowned Australian surgeon and Chairman of the Commonwealth Medical Equipment Control Committee (MECC). The MECC was responsible for making sure Australia was stockpiled with drugs and equipment needed to withstand invasion, but also able to support our troops in the field.

It must have taken someone with “connections” to obtain approval for the release of penicillin by Dr Chester Keefer who was in charge of development of the drug at John Hopkins University in America. That person may well have been Dr Bill Newton, who at the request of Leo Harrison asked his brother whether he could help. Other possibilities include Professors McPherson Brown and James Bordley who had been colleagues of Keefer at John Hopkins and were now back in Australia.

Whatever the process, contact with America was established through Mr. LR Macgregor, Director-General War Supplies Procurement Mission in Washington. Later, Sir Alan Newton personally thanked Mr Macgregor on his return to Australia after 6 years in Washington for his involvement in this incident.

On a Friday night an A1 priority cable sent to Macgregor resulted in his seeking the approval of the surgeon-general of the US army for the release of 1,000,000 units, thought to be sufficient for one person and worth about £30. Packed in dry ice, the drug was carried in a bomber to Australia and first administered on the Thursday morning, less than one week later. By the following Monday Peter Harrison was able to eat a normal meal – a remarkable recovery.

Despite the immediate and significant improvement in Peter Harrison’s condition, within a week another lumbar puncture ascertained that the infection was still present and active. This led to further communications with the United States to procure Antipneumococcic Rabbit Serum, which also aided in the recovery of Peter Harrison. He remained in hospital approximately six weeks after receiving the penicillin. We know now that the penicillin dosage was not sufficient for one person and significantly less than what would be administered today. We would give 1,000,000 in one dose today.

The value of penicillin, although still in its experimental stages, had been shown, particularly in war zones. Accordingly, in October 1943 CSIRO scientists were sent to the United States and before long small quantities of the drug were being made by the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories. Australia then became the first country in the world to make penicillin available for the treatment of civilians.