This account records an incident in the Japanese submarine campaign off Australia and the efforts of the RAAF and VAOC to protect coastal shipping.

As the attractive blonde 17 year old rode her push bike to work on the cold morning of 22 July, 1942, the Japanese submarine I-11 had already torpedoed the American Liberty Ship, SS William Dawes approximately 15 miles off the Australian east coast township of Merimbula. Lorna Stafford was a member of the little-known Volunteer Air Observers Corps, which was established by the Royal Australian Air ForceDirectorate of Intelligence in the last few months of 1941.

The VAOC’s work was the sighting and reporting of enemy aircraft over Australian territory as well as coastal surveillance. Observation posts were established and manned by volunteer observers under the control of a Chief observer and linked to control posts under a civilian Commandant. The control posts such as where Lorna reported to begin her daytime shift used existing Civil Defence and Volunteer Defence Force facilities wherever possible. Any relevant information was reported directly to the main control posts in each state capital city. Communications were carried by an `Airflash’ priority system through the normal telephone system backed up by B3 radios between control and main centres. Using this method which overrode the normal telephone lines, it allowed information to be transmitted to a main control post in one or two minutes. All volunteers were to be of Australian/British nationality, of good character and have passed the basic hearing and eyesight test. All went through a stringent aircraft recognition training course and where possible, members were recruited locally. Lorna Stafford lived close to the small fishing town of Tathra where the observation post in a small wooden hut had been established because of its commanding view up and down the coast. It was freezing in the winter and hot in the summer and was only equipped with the mandatory log and code books, telephone, clock and binoculars.

Lorna normally began her official day timeshift at 9 am (9 am-1 pm) but had arrived early this particular morning and was shown a report from the night shift observer that at approximately 5.30 am that morning, a loud explosion was heard out to sea down towards Merimbula. Little did the teenager realise she was about to become a part of military history generally unknown today outside the local area.

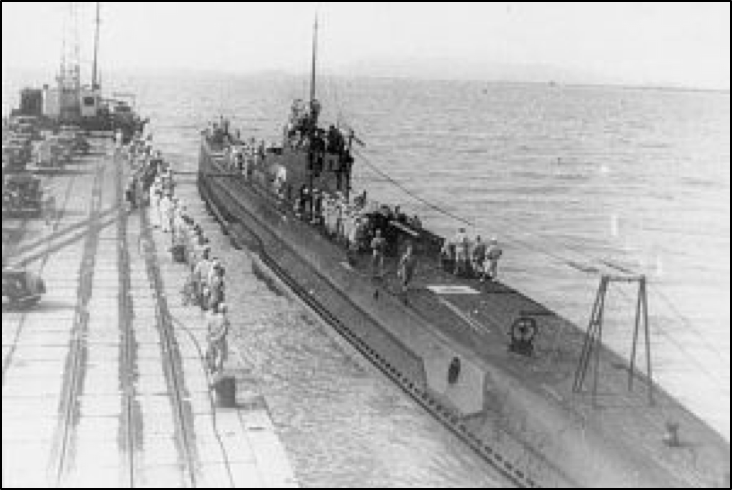

In mid July, three type A1 Japanese long-range fleet submarines arrived off the east coast of Australia from the shipyards in Kure, with orders to attack all merchant shipping. The largest boat was the 2900 ton I-11 commanded by Commander Tsuneo Shichiji. The I-11 was also the flagship of Rear Admiral Kono Chimaki’s 3rd Submarine Squadron. The Type A1 was developed from the Type J3 design with a hangar opening forward from the conning tower. This was for access to a forward mounted catapult, which allowed advantage to be taken of the forward movement of the boat to launch the `Glen’seaplane. The I-11 and the two other boats, I-9 and I-10 were all equipped with communications equipment that enabled them to operate as command ships for groups of submarines. For the time, they were massive boats with a crew of 114 officers and men. All three submarines operated along the east coast of Australia from July to the beginning of August and official Japanese records credited the three submarines with sinking ten Allied merchant ships. In fact, only three were sunk, all by the I-11.

Commander Tsuneo Shichiji began his war in the I-11 with the night sinking of the Greek ship, SS George S Livanos (4835 tons)approximately 15 miles off Jervis Bay on 20 July. Fortunately, there were no casualties. Three hours later in almost the same area, the I-11 torpedoed and sank the American vessel, SS Coast Farmer (3290 tons). After the attack; the I-11 surfaced to examine the sinking ship by searchlight and submerged a short time later. The crew were not harmed in any way but one crew member had been killed in the attack. Twenty seven hours later, in the early morning darkness of 22 July 1942, the I-11 attacked the 5576 ton American Liberty Ship, SS William Dawes ((SS William Dawes was named after the revolutionary patriot minuteman who rode with Paul Revere and Samuel Prescott during the American War of Independence. She was launched from the Oregon Shipbuilding Corporation, Portland on 7 February, 1942 as a United States Army Transport.)). The Japanese Commander’stactics were to attack ships at night, preferring surface attacks using a combination of torpedoes and the 155mm deck gun.

The William Dawes had left the South Australian city of Adelaide on 19 July bound for Brisbane, Queensland’s capital city, with a complement of 39 Merchant crew, 15 Naval Armed Guard and a cargo according to the Australian War Memorial records of 82 x quarter-ton jeeps, 33 x half-ton CPRs, 72 half-ton pickups, 2 x one and a half ton cargo trucks, 12 x two and a half ton cargo trucks, 12ambulances, 12 half track vehicles and with explosives and other sundry Army stores, the total service cargo was approximately 7,177 tons. Three soldiers, a Lieutenant and two enlisted men, were also on board as the cargo was the equipment and stores of the United States Army 32nd Infantry Division (Michigan and Wisconsin National Guard) that had arrived in Adelaide from San Francisco on 14 May. They had been training at a military camp outside the city but early in July 1942 were ordered to transfer all personnel and equipment to CampTamborine near Brisbane. Most of the personnel were sent to their new camp by train but some were dispatched on five ships. The William Dawes was not part of this convoy of ships but steaming alone, unescorted, and was approximately midway between Merimbula and Tathra when the torpedo struck.

The first torpedo the Japanese fired at the Liberty ship that fateful July morning struck the stern section, causing massive damage from the entire after end of the ship to the centre of No. 5hatch. This section separated and sank a short time later, taking with it the steering gear, the propeller, stern deck gun and the two anti-aircraft guns. The engine room flooded through the shaft alley. There were nine people in oron the after deckhouse. Two were on watch at the four inch gun that was atopthe deckhouse and seven were asleep in their compartments. The two on watch were presumably killed instantly and of the seven below, four, including Signalman Minton, escaped. The others were trapped and perished.

The Captain had ordered the lifeboats lowered and the ship abandoned but instructed the boats to pull away from the ship and standby until daybreak to see if the ship could be saved. Sometime later, a second torpedo struck the ship amidships, setting the ship on fire, which started a series of explosions. Just after the fires had started, the crew were horrified to see the giant I-11surface about 1500 yards from the burning ship and lifeboats just before sunrise, presumably to observe or record their handiwork, and had submerged without interfering with the crew in the lifeboats a short time later. William Minton saw the submarine surface and remembers being extremely worried as he had heard of submarines ramming or machine gunning lifeboats. Realising the ship was unsalvageable, the Captain ordered the four lifeboats (one motorised)to head towards the nearest land, about 12 miles away. They had gone some distance when the rescue trawler from Merimbula arrived. The survivors were collected together and the four lifeboats were towed back to Merimbula. The local police constable on board the trawler compiled a list of the dead and wounded.One Army servicemen plus four Naval Armed Guard had been killed and four wounded, one badly. The dead soldier, twenty five year old Corporal Gerald O.Cable, Service Company, 126 Infantry had the dubious distinction of being the first 32nd Infantry Division serviceman to be killed in action while serving with William Dawes gun crew. Shortly afterwards, Camp Tamborine outside Brisbane, was renamed Camp Cable in his honour by his fellow soldiers. The 32nd were the first Americans to meet the Japanese in New Guinea.

Lorna was unaware a submarine attack had taken place but from her vantage point in the Tathra observation post, and with the aid of her binoculars, she could see the ship constantly changing course. With the steering gone, the ship was at the mercy of the ocean currents. As the drama at sea was unfolding, Lorna was reporting her observations to the majorVAOC HQ at Moruya and making rough timeframe sketches of each event as it unfolded. Lorna’s efficient and speedy reports to her control station in Moruya had enabled the fishing trawler to be quickly dispatched to the scene to rescue any possible survivors. Another trawler was sent from the nearby fishing town of Eden as a stand by. A fishing boat was also sent out from Tathra and the local people, now aware of the tragedy that had taken place out at sea, gathered together to get food ready for the expected arrival of any survivors. They were bitterly disappointed when they heard the rescued crew had gone to Merimbula instead.

The Japanese submarine had long since gone when a Royal Australian Air Force aircraft arrived on the scene just after sunrise.

The RAAF Operations log book records the flight crew reported seeing 12-15 persons in each of the four lifeboats and that the vessel was on fire and a number of service trucks and jeeps on deck were also burning. The crew investigating the devastated ship also reported sighting a submarine at 10.15 am, three miles south of the stricken vessel moving southeast. The aircraft attacked the submarine with bombs. The aircraft’s target could have been Shichiji’s submarine, as his course did take him south, or a whale mistaken for a submarine, but official Japanese record sindicate no attack on the I-11 taking place. The burning wreck of the William Dawes finally sank stern first around about 4.30 pm the same day.

Most of the remaining crew were gladly accommodated in the homes of the local townspeople until the military authorities could make further arrangements as to their future.

Commander Shichiji continued his patrol further down the Australian coast where he again used his night surface attack tactics and fired one torpedo at an Australian vessel, SS Coolana (2,197 tons). The Japanese thought they had hit the ship but as the vessel showed no sign of sinking, Shichiji ordered the use of the deck gun. In the rough seas, it was difficult to aim and when the Australian vessel began to send a SOS signal, it was time to leave the scene. Fortunately, there was no damage to crew or ship.

Two days later on 29 July, the giant I-11 almost became a victim herself. One of three RAAF Beaufort aircraft patrolling off Cape Howe sighted an object 22 miles NE of Gabo island, identifying the submarine on the surface. After several attacks a large patch of oil convinced the crew that they had accounted for the submarine. It was a very close call and it was the first time the I-11‘s crew had been in a bombing attack and it shook them up rather badly. The only damage to the submarine was some cracking to the wooden decking and a few embedded bomb fragments in the deck.

The I-11began her next war patrol during the first week of August in a new theatre of operations, this time in the Pacific. Over the next 2 months, there were only two events worthy of note during this phase of her operations. On 6 September1942, the submarine managed to slip past a screen of escort ships off Espiritu Santo and fired a spread of torpedoes at the aircraft carrier, USS Hornet (CV8) but a circling aircraft spotted the torpedoes and dropped its bombs disrupting the torpedo’s direction. All missed the carrier ((The USS Hornet had, back in April, launched the famous ‘Doolittle Raid’ where l6 B25s attacked Tokyo, Nagoya and Kobe in one of the most daring raids of modern warfare. Although the I-11 failed to sink her, the carrier would fall victim to the Japanese the following month in the battle of Santa Cruz Islands, one year and six days after she was commissioned.)).

The next day, the I-11 was attacked by a PBY Catalina from the “Black Cats” squadron (VP-11) and may have suffered some damage as she returned to Kure for repairs on the 22 September.

Early January 1943, a repaired, provisioned and ready for action I-11 returned to active service in the Pacific. But the earlier successes of 1942 eluded the I-11. On 20 July 1943 off San Cristobal, New Hebrides in the Solomons, the I-11 fired two torpedoes at the Australian light cruiser, HMAS Hobart. One torpedo hit, killing 15 crewmen and wounding seven others but the Hobart managed to limp into Espiritu Santo and carry out temporary repairs. On 11 August, the I-11torpedoed and damaged the 7,176 ton American Liberty ship, SS Mathew Lyon off Noumea, New Caledonia. With nothing much to show for almost nine months of operations at sea, the I-11 returned again to the Kure shipyards for repairs on 26 September.

Three months later, the giant I-11 and her crew lay on the bottom of the ocean, listed officially as an operational loss off Ellice Island. Some historians suggest she hit a mine but the cause of her demise has yet to be historically proved.

The Japanese were never in a position to seriously disrupt the flow of war material and other essential goods between America and Australia as they lacked the resources, material, skill and proper direction. If the Imperial Japanese Navy High Command had adopted the GermanHigh Command’s priority of sinking merchant ships, the disruption of cargo between America and Australia might have had an effect on the ability of the Allies to conduct the war. Certainly it would have made it much more difficult to keep the supply lines open. Japan sent more than 24 submarines to operate in Australian waters during 1942-44, and of the 49 merchant vessels attacked, only24 were actually sunk (a total of 117,000 tons). The overall Japanese submarine warfare campaign was not all that impressive.

What was impressive was the contribution by the volunteers of the Air Observers Corps who, in the overall picture of Australia’smilitary involvement in WW2, has been all but been forgotten. The VAOC peaked in manpower at 24,000 members in 1944, manning 2,656 observation posts and 39control posts. Between January 1943 and August 1945, the organization had`definitely’ saved 78 aircraft, `substantially’ aided 710 and `assisted’ a further 1,098. Assistance given ranged from supplying tea and biscuits to downed airmen to advising their bases of their whereabouts and guarding aircraft. When one adds up the ship spotting and naval co-operation tasks, the corps has an honourable record. They were officially disbanded on 10 April 1946.

Lorna, now Mrs Waterston, lives in Kalarunear Tathra. To honour her contribution to the war effort and her part in the events of 22 July 1942, a small memorial plaque was placed in Tathra’s memorial park by the local Lions Club. A fitting tribute, not just to one single VAOC volunteer but to them all and to those brave men who lost their lives in SS William Dawes.

The Australian Government also paid a tribute to the men who lost their lives on the William Dawes, but 62 years later. An Australian diving expedition called the Sydney Project Diving Team had been planning for over six months a dive on the William Dawes. The wreck’s location was established 10 miles from where she was torpedoed and 12 miles from the coastal town of Bermagui. On 25 October 2004, two divers not only found the wreck upside down in 135 metres of water but broke the existing New South Wales diving record at the same time.

The wreck has remained untouched since its sinking and is a virtual time capsule. The Australian Government declared the site to be a ‘historical shipwreck’, which will enable divers to visit the ship but not to remove or disturb relics without a permit. An official government communique stated; `The William Dawes deserves our protection as it may be a war grave of the five lost crew.’ May they rest in peace!

Author: Wright, Ken

Publication: September 2005 edition of the Naval Historical