Armistice Day is remembered as the day World War One ended, but for naval historians Britain’s greatest victory came 10 days later. Operation ZZ was the code name for the surrender of Germany’s mighty navy.

For those who witnessed “Der Tag” or “The Day” it was a sight they would never forget – the greatest gathering of warships the world had ever witnessed.

It was still dark in the Firth of Forth when the mighty dreadnoughts of the Royal Navy’s Grand Fleet began to raise steam and one by one let slip their moorings.

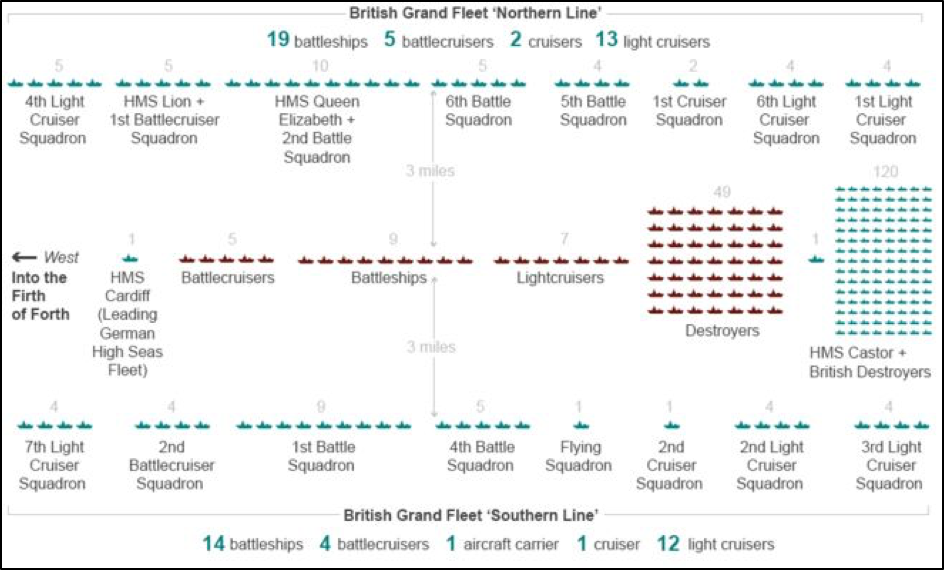

The huge shapes of more than 40 battleships and battlecruisers began to ease out, course set due east. As the procession of steel headed for the open water of the North Sea, more than 150 cruisers and destroyers joined them. The mightiest fleet ever to sail from Britain’s shores was heading for a final rendezvous with its mortal enemy – the German High Seas Fleet.

Present were HMA Ships Australia (I) (Captain TN James, RN), leading the British port line, Melbourne (I) (Captain EA Rushton, RN) and Sydney (I) (Captain JS Dumaresq, CB, MVO, RN).

Victory would be total. But there was to be no battle. After four years of naval stalemate, this was the day when Germany would deliver her warships into British hands, without a shot being fired.

The date was 21 November 1918. World War One had ended on land 10 days earlier, but this was to be the decisive day of victory at sea.

After tense negotiation, Germany had agreed to deliver its fleet, the second biggest in the world behind only the Royal Navy, into the hands of the British. The mighty assembly steaming to meet theGermans was a reception committee so overwhelming that it would brook no change of plan.

Operation ZZ saw the mightiest gathering of warships in one place on one day in naval history.

It was a sight those who saw it would never forget. The unnamed correspondent for the Times, watching from the deck of the British flagship the dreadnought HMS Queen Elizabeth, was overwhelmed:

“The annals of naval warfare hold no parallel to the memorable event which it has been my privilege to witness today. It was the passing of a whole fleet, and it marked the final and ignoble abandonment of a vainglorious challenge to the naval supremacy of Britain.”

Two days earlier nine German battleships, five battlecruisers, seven cruisers and 50 destroyers had set sail, heading west. Under the terms of the Armistice which had ended the war they were to hand themselves over in the Firth of Forth, before being brought to the lonely Orkney anchorage of Scapa Flow.

As he led his fleet out of the Firth of Forth, Sir David Beatty could count on an overwhelming superiority to forestall any final show of German defiance. As well as his ships, he was joined by five American battleships and three French warships.

Nevertheless, he was taking no chances. His orders issued the night before were clear – ships were to be ready for action:

“Turrets and guns are to be kept in the securing positions, but free. Guns are to be empty with cages up and loaded ready for ramming home. Directors and armoured towers are to be trained on. Correct range and deflection are to be kept set continuously on the sights.”

As the Grand Fleet sailed into the North Sea, it formed two massive columns, one to the north, one to the south, six miles apart. Just before 10:00 it met the Germans, being led to their surrender by the British light cruiser HMS Cardiff. The Allied columns swung round to due west, forming an overwhelming escort on either side of the Germans.

The Times correspondent described the scene:

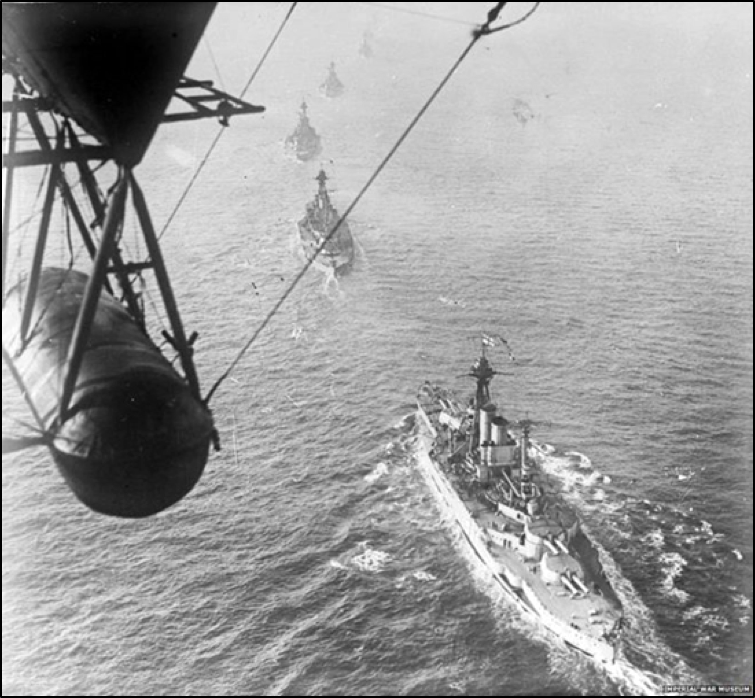

“Between the lines came the Germans, led by the Cardiff, and looking for all the world like a school of leviathans led by a minnow. Over them flew a British naval airship. First came the battlecruisers, headed by the Seydlitz.”

By late morning it was over. The German ships, missing one destroyer which had struck a mine and sunk, lay at anchor off theIsle of May in the outer reaches of the Firth of Forth, surrounded by their jailers. Beatty rammed home the message with a curt signal:

“The German flag will be hauled down at sunset today and will not be hoisted again without permission.”

Before holding a service of thanksgiving on board HMS Queen Elizabeth, Beatty thanked the sailors of the Grand Fleet.

“My congratulations on the victory which has been gained over the sea power of our enemy. The greatest of this achievement is in no way lessened by the fact that the final episode did not take the form of a fleet action.”

At the surrender each German vessel was assigned to the custody of a British ship, which sent aboard a party to inspect it for hidden explosives and instruct the captain. HMAS Melbournehad responsibility for the German light cruiser Nurnberg while HMAS Australiawas given the battlecruiser Hindenburg. HMAS Sydney was assigned to escort another Emden, the light cruiser named to honour Sydney’s opponent at the Battle of Cocos.

As darkness fell on 21 November 1918 buglers played “making sunset” and cheers rang out from the sailors of the Grand Fleet.