July 2019

Early Career

Francis James Ranken was born in 1864 at ‘Saltram’, Eglinton, near Bathurst. He was the eldest son of James Australian Ranken and was educated at All Saints’ College, Bathurst. His grandfather, George Ranken, was one of Bathurst’s earliest settlers, and was granted 2,000 acres at Eglinton in 1822. Francis went to sea at the young age of 14 in a clipper ship, and eventually became an officer in the Orient Line. He joined the Royal Navy Reserve (RNR) as a Sub-Lieutenant in August 1891 and after training resumed service with the Orient Line. He married Menina Blanche Paige (who was born in Maryborough, Queensland in 1863) in London in 1893.

He was serving as Chief Officer in RMS Orient when she sailed from Melbourne for Sydney on 9 January 1897, encountering very rough weather after passing Wilson’s Promontory. On the next afternoon the brig Phyllis was sighted flying distress signals and Orient learnt that the crew were starving. Although a huge sea was running, a boat with Ranken and a crew of six managed to row to the brig and transfer food. The return journey was even more perilous as the wind and sea heightened and the men were finally pulled from the boat onboard the Orient. The boat could not be recovered as the sea was too rough. Whilst in Sydney, Orient’s Captain and boats crew’s efforts were recognised by the National Shipwreck Society and Ranken received a gold medal and a pair of binoculars.

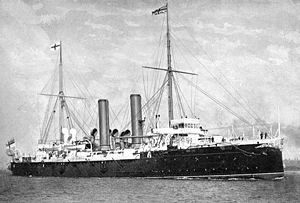

He was promoted to Lieutenant RNR in September 1897 and by 1899 had completed one year’s full-time service in the RN and also completed one of the short courses in Gunnery and Torpedoes available to reserve officers. In November 1899 he was appointed to the first-class cruiser HMS Galatea for his second period of 12 months training, completing this full-time service in the first-class cruiser HMS Royal Arthur, which he joined in February 1900. Royal Arthur was the flagship for the Imperial Squadron in Australia. In April 1900 Royal Arthur escorted the Royal Yacht Ophir carrying the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York (the future King George V) to Australia to open the new Federal Parliament in 1901.

In July 1905 he was appointed to the third class protected cruiser HMS Mildura in the Australian Auxiliary Squadron, for a third period of FTS. In May 1906 he was appointed to HMS Torch, an Alert class sloop and tender to the cruiser HMS Pyramus to complete his 12 months training.

At his own request he was placed on the retired list in December 1907 and returned to Australia to undertake poultry farming at Castle Hill, NSW. He had completed three years full-time service in the RN and had completed both short courses available for Reserve officers in Gunnery and Torpedoes.

Ranken’s Contribution to the Introduction of a Minesweeping Capability

The Admiralty wrote to the Naval Board in late 1914 outlining the impact of mining in home waters and suggesting appropriate measures should be taken as it was likely the Germans could mine in bases abroad used by British and allied navies. Despite broad policy directives from Navy Office on establishing a minesweeping capability, little action resulted and discussions dragged on. What was needed was a champion to understand the issues and break the seemingly continuous dialogue between Navy Office and the local naval authorities. That was to come with the recruitment of a 52 year old Master Mariner, Francis Ranken. On 8 February 1916 Ranken joined the RANR (Seagoing) as a Lieutenant Commander (Temporary Service) and was posted to HMAS Penguin before assuming command of HMAS Gayundah in May. Given that he joined for temporary service around the time the Board decided they wanted a reserve minesweeping service, it is suggested he was recruited to oversee and manage the introduction of a minesweeping capability.

Ranken produced a report on minesweeping arrangements for Sydney and the report formed the basis for establishing a minesweeping service in the RAN. By early 1917, matters started to speed up as on 16 February advice had been received that a vessel had sunk off Colombo, believed to be due to mining. It was decided that because of the potential threat to Australian ports, a minesweeping organisation was to be introduced as soon as possible at Sydney, Melbourne and Fremantle. Whilst the Director of Naval Auxiliary Services (DNAS) in Navy Office began staffing the administrative details for the minesweeping organisation, the RN advised the Naval Board by telegram a week later, on 27 February, that a mine had been found and exploded in a sweep off Colombo. At a Board meeting on 28 February 1917, it was formally agreed that minesweeping sections would be set up at Sydney, Melbourne and Fremantle. Suitable vessels would be leased and converted for minesweeping.

On 1 March 1917, Navy Office advised the Prime Minister, Billy Hughes, that a Minesweeping Service was to be established immediately. That day, Ranken was posted to the staff of DNAS to manage the introduction of a minesweeping capability into the RAN. The next day, Cabinet approved the measures proposed. The Section would be a component of the Royal Australian Naval Brigade (RANB), which was administered by DNAS. The RANB was the RAN’s primarily non-seagoing reserve organisation during the First World War. The Brigade provided men for overseas service including the naval component of the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force that occupied Germany’s Pacific territories, and the Naval Bridging Train that operated at Gallipoli and Egypt. The Brigade was also heavily employed at home guarding naval installations, operating harbour patrols, inspection services and boarding parties, and manning lookout and wireless stations.

The organisation for the RANB (Minesweeping Section) would enlist personnel from the trawler industry and other seagoing vessels into the Brigade for temporary service for training and then returned to their normal employment. Whilst DNAS remained responsible for personnel matters, the implementation of the organisation to undertake minesweeping activities in each State was under the supervision of the local Naval Commanders. However, the overall co-ordination of the introduction of this new capability across all States was managed by Ranken working from DNAS. He wasted no time and the recruiting of suitable personnel for the recently announced Minesweeping Section of the RANB commenced in late March 1917.

Minelaying by the German Raider Wolf

The German raider Wolf (formerlly the Hansa freighter Wachtfels) was 5,809 GRT, 135m long, had a speed of some 11kts and a range of over 32,000 nm. She carried seven 150 mm guns, many smaller weapons, four torpedo tubes and at least 497 mines, together with a two seater seaplane. Under the command of Korvettenkapitän (Lieutenant Commander) Karl August Nerger she sailed from Kiel on 30 November 1916, finally returning home on 24 February 1918 with 467 prisoners and substantial valuable seized cargo. She ‘lived off the land’ for a cruise of 64,000 miles, surviving on supplies and coal plundered from captured vessels. In 15 months at sea, Wolf captured 14 ships (sinking twelve) and also laid minefields that sank another 13 ships. Minefields were laid at Cape Town, Cape Agulahas (South Africa), Bombay, Colombo, Australia, New Zealand and the Anambas Islands (near Singapore).

Wolf’s voyage was the most successful undertaken by any German raider and no doubt reinforced the value of the merchant raider concept of operations, particularly the use of an embarked aircraft (this concept was again used by the Germans to great effect in World War II). The Wolf, without support of any kind, had made the longest voyage of a warship during World War I and had steamed almost 2.5 times around the globe. Her actions over a wide area between Cape Town and New Zealand caused confusion and the allocation of a large number of forces to try and locate her.

Wolf crossed the Tasman after mining off New Zealand to mine near Gabo Island (off Cape Howe) on the night of 3-4 July 1917. She laid 30 mines, and would have lain more but for the appearance of a vessel that she took to be an Australian cruiser.

Sinking of SS Cumberland

On 6 July 1917, just two days after Wolf had laid her minefields, the SS Cumberland was heading down the east coast for a voyage to the United Kingdom after picking up cargo in Townsville, Bowen and Sydney. The 9,660-ton steam ship reported at 0835 that she had struck a mine ten miles south of Gabo Island. The Department of Navy had given written route directions that would keep Cumberland outside mineable water (outside the 100 fathom line). The Master, Captain McGibbon, later admitted that he disobeyed these instructions, and the ship was several miles inside his prescribed course.

Cumberland reported that she was sinking and required assistance. The ship had a hole some 21 by 14 feet in No. 1 hold and was taking water but struggled towards Gabo Island and grounded for urgent repairs around1400. By evening the ship had about 38 feet of water in No. 1 hold and 17 feet in No. 2 hold. The crew decided to temporarily abandon Cumberland and landed on Gabo.

Vessels were dispatched from Sydney and Melbourne with dedicated salvage equipment, including pumps and mooring gear. By the time they arrived, Cumberland’s holds, boiler room and engine room were flooded. Salvage operations commenced under the supervision of Captain Christopher Spinks of Vine Hall and Spinks Marine Salvage Agents, from Sydney The ship’s agent, acting on behalf of the owners the Federal Steam Navigation Company, was responsible for implementing the salvage arrangements.

Naval and Harbour Trust divers were deployed patching the hole by removing jagged plating and attaching sturdy timber bracing and patches made from layers of canvas. In addition, the bulkhead was repaired and the ship pumped out. However the cargo of some 2,000 tons of metal ingots was not removed. Several vessels were involved in the salvage including the Illawarra & South Coast Steam Navigation Company’s steamers Merimbula and Bermagui, and the tugs Champion and James Paterson from Melbourne.

After five weeks of strenuous repair work by divers and a dedicated salvage team, on the morning of 11 August the ship was refloated and the tugs James Patterson and Champion commenced a tow to Twofold Bay for further repairs. A salvage crew under Captain Spinks was onboard and the boilers were lit to maintain pumping of the holds. However, by evening, the weather had worsened and as the swell developed it became impossible for the tugs to make headway and Cumberland started to take on water faster than the pumps could manage. By 2200 the stricken ship had settled down by the bow and waves were now crashing over the deck hatches. By now it was clear the vessel’s situation was hopeless and Spinks ordered the ship abandoned. The tugs slipped the tow and Merimbula and Bermagui stood by to offer help, the former rescuing Cumberland’s crew. Shortly after the last of the crew reached Merimbula, the Cumberland sank bow first. She had been towed twenty-three miles before being lost and sank 18 miles from Eden in an estimated depth of 50-60 fathoms.

Sweeping the Gabo Island Minefield

At this stage there was no intelligence on Wolf’s activities, or the movement of any other suspicious ship off the Australian coast, however, given the depth of water where Cumberland was hit, it was agreed that mining was feasible. On learning Cumberland had suffered damage an inquiry was immediately ordered under Major George Steward CMG, Official Secretary to the Governor General (Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson). His report to the Prime Minister, completed 18 September, found convincing proof that Cumberland had struck a mine. Whilst the Naval Board suspected an internal explosion, it recommended minesweeping to the Minister of Navy in order to resolve the question of the cause of the explosion. The area to be swept was based on the datum provided by Cumberland hitting a mine in the Gabo Island minefield.

On 26 September 1917, two trawlers (Gunundaal and Koraaga) were leased to undertake minesweeping off Gabo Island. (The third trawler, Brolga, was leased on 8 November). The crews for the trawlers were engaged for temporary service in the RAN Brigade. Lieutenant Commander Ranken was posted from DNAS to Penguin on 19 September to command Gunundaal and as Senior Officer Mine Sweeping Unit. He reported to the Captain in Charge HMA Naval Establishments, Sydney, Captain John Glossop CB, RN (of Emden fame), who was in overall command of their subsequent operations. The minesweeping unit sailed from Garden Island, Sydney eight days later on 3 October 1917.

It was intended that sweeping near the Cumberland datum commence on 5 October, however a gale delayed danlaying and sweeping was delayed by three days. The first mine ever swept by the RAN was swept on 9 October 1917. At 1325 Gunundaal and Koraaga were sweeping in 100 m depth of water near the location reported by Cumberland, when the sweep wire veered off Gunundaal’s winch. At 1405 Ranken asked the Mate to feel the sweep wire, and it was decided that there was nothing hung up on the sweep wire. At 1415 an explosion occurred shaking both ships fore and aft, and the location of the detonation of the mine was buoyed. Fortunately the mine was deep when it detonated. After engaging the mine mooring the sweep wire probably dragged the mine down as it ran up the mooring, and then rode up the mine and bent a horn which exploded the mine. The mine detonation was 4.8 miles from Gabo Island Lighthouse, and Ranken reported that the stone buildings were shaken. There was no plume; however the water boiled up over an area of about 80 square metres.

The sweeping of this first mine was reported the same day by telegram (via the Gabo Island Lighthouse) to the Captain-in-Charge, Sydney. At 0930 on 10 October Ranken received orders from the Captain Glossop (presumably from a telegram collected that morning at the lighthouse) to provide a full written report of the discovery of this mine. At 1100 Gunundaal and Koraaga weighed anchor and proceeded to Eden to post the report. The letter on 10 October appears to have been written in haste by Ranken, keen to resume actual sweeping. Ranken’s writing was normally copperplate. The Minister for the Navy, Sir Joseph Cook, promptly released statements on this initial sweeping operation, and these were reported by the newspapers. The psychological warhead of mining would have generated public shock and concern commensurate with a weapon that was new to Australian waters.

There were five more sweeping deployments in October, November, December and January 1918. A further eight mines swept making a total of eleven mines were swept under Ranken (until 21 December) and one in January 1918. His final Report of Proceedings indicates the adverse weather conditions the minesweepers encountered on these deployments.

Ranken gave an interview which was published in the Sydney Morning Herald on 3 November on the minesweeping operations and the minefield. The article gave more detail on the mines than the earlier press release made by the Minister the Navy. The fact that Ranken had spoken to the press incurred the wrath of the Naval Board with the Second Naval Member (Captain Henry Cochrane RN) finding Ranken’s reasons, which indicated the information was cleared by the Censor, unsatisfactory, particularly as the Board has issued explicit instructions forbidding giving statements to the press.

The Naval Board proposed not to re-employ Ranken in the minesweeping service. Ranken requested on 1 December 1917 that the Naval Board reconsider this decision, but the decision to not re-employ him in minesweeping was confirmed on 15 December. Given Ranken’s extensive background in setting up and managing the minesweeping capability, the general paucity of RAN minesweeping expertise and the ‘good news’ style of article, it is surprising that the Naval Board acted so quickly and took such a hard line on what must be considered a minor indiscretion.

Ranken returned to Sydney on 22 December and did not participate in further minesweeping operations. However, he remained posted to Penguin and his minesweeping expertise continued to be used for minesweeping analysis in Brisbane and Townsville. He resigned in September 1918 and the Navy lost one of its most experienced minesweeping experts. He returned to poultry farming at Castle Hill.

In March 1919, the Admiralty wrote to the RAN calling for recommendations for awards in respect of minesweeping service. This was an unusual request as it was the only time the Admiralty had communicated with the RAN on the subject of honours and awards. Rankin’s old boss, Captain Tickell, the Director of Naval Auxiliary Services, drafted the response to the Admiralty, recommending four personnel, including Ranken. Captain Glossop had also recommended Ranken’s name be included. The wording was precise, stating Ranken: ‘Was Officer Commanding Minesweeping operations and successfully swept the enemy mine-field off Gabo Island, SE Australia when 10 enemy mines were destroyed. This Officer showed marked ability and devotion to duty during the minesweeping operations off this coast.’

In October 1919, Ranken received an OBE in recognition ‘for valuable services in minesweeping operations’ during the War. In July that year the RN had promoted him to Commander RNR (retd) ‘in recognition of services rendered during the War’ and in September 1920 he was awarded the Royal Navy Reserve Officers’ Decoration.

Conclusion

Frances Ranken died at Parramatta on 1 September 1929 and was cremated the next day at Rookwood Crematorium. They had no children and his wife, Menina Blanche Paige-Ranken, who was an accomplished pianist and well known in Sydney music circles, died in 1947.

Ranken had a remarkable life and made a significant contribution to the RAN’s minesweeping capability in World War I. His actions when as Chief Officer of RMS Orient taking charge of the boat delivering supplies to the brig Phyllis in ferocious sea conditions, indicates his courage and ability to succeed in arduous conditions. The rapid and successful implementation of the Minesweeping Service from a virtual vacuum no doubt reflected his considerable organising abilities and management skill. His command of the successful minesweeping campaign in adverse conditions was an impressive record. It is fitting that he was recognised for his service and achievements. It is interesting that the RN conferred a promotion to Commander RNR and a Reserve decoration on him which suggests that he had left a positive impression from his time in the RN and that his old service recognised what he had accomplished in sweeping the Gabo Island minefield.

Publication March 2014 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Hector Donohue