August 2019

By Florence Livery

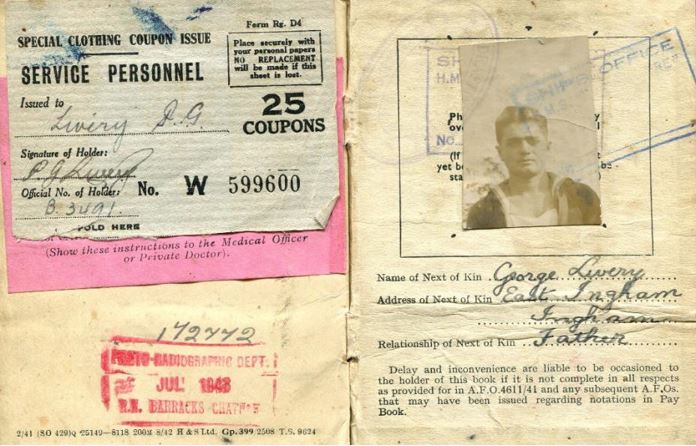

My father, Panos (known as Pino) George Livery died in 1996. Fortunately for us, he left behind a very rich source of history, his World War II diary, his collection of photographs and postcards and his unpublished memoirs. These memoirs include the war years and his life growing up in Ingham, North Queensland. It is these records that I have used as the basis of this article.

Try to picture this. It is 1923, big George and tiny Evangelia, with three-month-old Panos and two-year- old Constantine, have just sailed half way across the world from the remote Greek island of Kastellorizo and disembarked at Ingham Railway Station. Uncle Jimmy had urged them to come to the tropics, to come to North Queensland where they would find their pot of gold. ‘The rainbow ends here,’ he told them.1 Ingham, a small cane-growing town in the middle of nowhere, the small Greek community at the bottom of the pecking order.

Protestants, Catholics, Italians and last of all, the Greeks. Before George knew it and after many arguments, Jimmy had left Ingham. ‘I’m not wasting my time here. I’m heading south to seek my fortune.2 George and Evangelia were left stranded as three more children arrived in quick succession. They persevered with their minimal English, worked hard to get by in the tropics as best they could in the face of heat, humidity and floods. The boys were naughty and mischievous, with boxing lessons by their father a must. Then along came the 1930s and the Great Depression. What would save the boys from this? WWII of course!

The three older boys could not wait to enlist. In 1942 Pino enlisted in the Navy, Con was already serving in the Army and a year down the track Argus would join the Air Force. Three sons at war.

Six months after enlisting, Pino was on board HMAS Canberra in the Pacific Ocean where he faced what I would call his first nightmare. I must stress that these are my words, not his. Pino never used such confronting words in his memoirs. He just told it like a yarn. To him it was part of the journey.

On 9 August 1942, HMAS Canberra absorbed 24 torpedo hits within two minutes from enemy fire3 and this was only the beginning. Both boiler rooms were hit and consequently steam to all units immediately failed. All power for pumps, firefighting and armament had gone. Pandemonium was magnified as the shellfire hit the gun deck and the bridge where Captain Getting was mortally wounded. In the fire, rain and dark, the ship listed and the call came to abandon ship. 4 Where was Pino? Five decks below in the cordite handling room, along with seven others, trapped, the hatch sealed from above for fear of fire spreading and exploding the ammunition. No power. No air-conditioning. No lighting. Seven men taking it in turns to bang on the hatch with an iron bar, precariously perched on the upper rungs of the ladder. Fatigued bodies, no ventilation and no upper body strength. Luckily, over an hour later someone came their way looking for dead bodies, heard the noise and opened the hatch. The boys eventually got to the top, the fire had spread, the ship was going down fast and other allied vessels were under fire as they attempted to pick up survivors. To me the most telling part of this story comes next, when Pino said to his mate George Smallwood, after being on the upper deck for a couple of hours, ‘George, I am all wet, buggered and nervy. I’m getting on the next ship that pulls alongside no matter what.5

In time, along came USS Blue and George jumped first. It was only George’s outstretched hand from the other side that got Pino over. George called out from USS Blue, ‘When the ships become level, jump and grab the handrail and I will grab your hand. It was only two feet but if misjudged he could have fallen through the gap. As Pino reflected, ‘The bloke before me missed.6 Imagine what else he saw and tried to erase from his memory.

Pino’s parents received two telegrams. The first, ‘Sorry your son has died at sea. ’ The second, a few days later, ‘Correction, he survived!’ Pino was granted 14 days Survivor’s Leave – 84 dead, 109 physically injured and an untold number emotionally scarred before his very eyes.

Pino then spent the next few months based at HMAS Brisbane carrying out boom duties whilst patrolling the coastal waters. On 2 February 1943 he was drafted to HMA London. The Royal Navy (RN) had offered the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) HMS Shropshire as a replacement for HMAS Canberra. Pino became a member of the small HMS Wolfe draft, one of several contingents funneled across the world to pick up HMAS Shropshire.

Once Pino was five decks down below wondering whether he would ever see daylight again and several weeks later, on board USS Hermitage (troop transport), he was greeted by the iconic Aloha Towers Lighthouse as they pulled into Honolulu Harbour. Six hours shore leave gave Pino just enough time to visit Waikiki Beach and be photographed against the artificial backdrop of the velvet green Kalaupapa Cliffs, smooching up to a hula girl, his pal doing likewise to make up the foursome.

Seeing the world with his mates, a few days later Pino landed at San Francisco, followed by seven wild and wonderful days travelling overland to the east coast. As one of the boys said, ‘The next seven days were pure luxury for an 18-year-old Ordinary Seaman.’ 7 Imagine the excitement of these young sailors, seeing the Golden Gate Bridge on arrival, then off to places like Reno, Salt Lake City, the Rocky Mountains, Denver, Omaha, Cheyenne, Chicago, Indianapolis and Cincinnati. There were major stops and minor stops as they travelled in the stylish air-conditioned Pullman rail cars including a porter assigned to each car who attended to their every need. Meals were taken in the dining car with excellent food, (a welcome break from powdered eggs, salted meat and dehydrated vegetables) and a good night’s sleep was assured as the seats converted to comfortable bunks, (a vast improvement on hammocks).8 The train terminated at Newport News and the boys were then ferried across to the Norfolk Naval Shipyards.

On arrival at Norfolk, Pino and his mates were immediately assigned to HMS Wolfe, a submarine depot ship. Two days later they pulled out of dock and headed for New York City, sailing up the Hudson River past the Statue of Liberty berthing just a few blocks from Times Square. Five glorious days in New York awaited them and to fill in those hours on leave, between duties and awaiting orders, the party just got bigger and better! As Pino said, ‘It was just like a merry-go-round,9 as he saw the sights of New York, movies and shows, dropping in on the Canteens provided by the American Homefront and always ending up at Jack Dempsey’s Bar. Pino even got a glimpse of his movie idols Dona Drake and Jane Wyman at the Stage Door Canteen. Careless, reckless and free! Not bad for a boy from Ingham!

The party however, was about to come to an abrupt end. On 18 March 1943 HMS Wolfe pulled out of Pier 87, farewelled its neighbour at Pier 88, the 80,000 ton French liner SS Normandie which was lying on its side and steamed down the Hudson River into the Atlantic Ocean. As they sailed up the coast into Canadian waters they picked up other ships to form Convoy HX230, consisting of 46 merchants and 21 escorts.

As the winds blew a gale and they entered the icy Atlantic waters, little did Pino realize that the two preceding allied convoys, Convoy HX229 and Convoy SC122 were experiencing one of the greatest convoy battles (and German success) of the WWII Atlantic Campaign. Running in tandem but sailing independently, these two convoys were slaughtered by 38 U-boats from three wolf packs in a single sprawling action. The double battle involved 90 merchant ships and 16 escort ships. More than 300 allied seamen died and 22 allied merchant ships were sunk whilst one U-boat went down, taking with it all 49 of its crew. Wanting to follow-up promptly on these successes, Admiral Karl Donitz formed two new wolf packs and assigned them to the mid- Atlantic Air Gap. Convoy HX230 was identified in radio intelligence as the target of these two packs – the 17 strong Seeteufel (Sea Devil) and the 19 strong Seewolf (Sea Wolf).10 Nightmare number two for Pino was about to commence!

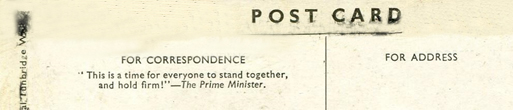

Surrounded by a false sense of security, Pino initially did not fear the U-boats, even though whilst on board Lord Haw Haw11 used his scare tactics over the airwaves, ‘You will not reach Scotland. Our U-boats packs will get you!

The following extracts from Pino’s 1990 memoirs13 interwoven with entries from his 1943 war diary however, reveal the emotional rollercoaster Pino experienced whilst crossing the Atlantic.

…We were right in the middle of the pack and the ocean was so rough that I thought they could not possibly line us up. At best, I thought, the stragglers could be knocked off but even then, it would be difficult as one minute they were on waves that took them up 60 feet and the next minute they were on waves that took them down 70 feet. At times we were going every which way – forwards, backwards, up and down, port to starboard. You could not even see the ship next to you, that’s how rough the Atlantic was and try sitting down and eating from a plate! Impossible and this went on for a week, day in, day out.

…But even in blustering and squalling conditions somehow the U-boats did get amongst us. The corvettes worked overtime but the best they could do was to rescue the survivors before the ocean swallowed them up. No other ship could stop, otherwise they would be sitting targets for a torpedo. The U-boats would stay and sort out their prey until the corvettes came along, when they would quickly dive away. All the poor corvettes could do was to drop a depth charge and hasten away. The U-boats were doing exactly as they pleased.

Diary entry 25 March 1943 – ‘Sighted iceberg, ship’s steering broke, ship nearly overturned’’

…At dusk on 25 March 1943, in very cold and troubled conditions, our captain advised us that HMS Wolfe’s steering had gone amiss and immediately placed all personnel to action stations, warning that because of the rough seas and lack of steering, to be prepared for anything, even to abandon ship.

Diary entry 26 March 1943 – ‘Everyone frightened, submarines around us and destroyers signaling, ships blowing sirens …. . Couldn’t sleep that night, ordered to sleep in clothes. ’

…The hooter blew constantly as we gradually fell behind the convoy. Soon we were all alone. At least, by now it was night. A corvette came close by, more of a gesture of help as the sea was tossing it around like a tennis ball. Scared and frightened, we thought that the end was near, especially when waves with such massive force covered the ship. At times the ship was absolutely swamped but miraculously it came up, again and again. That was the night of nights. No steering, U-boats, weather that was too rough to call stormy and on daybreak the convoy was lost from sight. By now, we had not slept for 48 hours and had eaten very little, but we did manage a little drop of rum to settle our nerves. Being an RN ship we received our daily ration of Jamaican Rum. You could feel it doing you good.

…The engineers worked on. By late morning, to our relief, our captain advised us that all had been repaired and we would hasten to join the convoy. 24 hours later we had repositioned ourselves as near to the centre as possible.

Diary entry 28 March 1943 – ‘Liberty ship hit by torpedo, drops back, can’t say if sunk …. Played poker all night, couldn’t sleep, too rough;’

…On nearing Iceland the convoy changed course to east south-east as the five Canadian corvettes were replaced by two British corvettes… but the reality of it all was said by the Pommy sailor on my watch, ‘Look chum, every trip you make across the Atlantic is in the laps of the Gods. ’ I really believed him. I was wrong to underestimate the power of the U-boats. No matter how rough the seas were the U-boats were always there, their periscopes skirting the outer edges of the convoy. They took their time and knocked off the larger ships, not bothering about the smaller ones, targeting the American Liberty cargo ships, which they knew would be worth their while.

Diary entry 29 March 1943 – ‘Sight aircraft from land bases, everyone happy;’

…However, it soon became a different story the day land-based aircraft took over patrolling the convoy. What a relief it was to see them flying over. All that day I did not see one periscope through the binoculars. To see one periscope was bad enough but to see two or three on the one day was terrifying. They just hunted in packs and now I say, 45 years later, thank God the seas were so threatening.

On 2 April 1943 HMS Wolfe split from the convoy, headed for Scotland and sailed up the Clyde River. At Gourock, the Shropshire draftees farewelled their pals and caught the train to London. With just enough time to have supper at the Westminster YMCA and squeeze in a look around the abbey they boarded the night train to Chatham Naval Dockyards, Kent where Pino first met HMS Shropshire.

Diary entry 2 April 1943 – ‘She looked like a factory, dirty, old and it was in a stinkin’ condition, looked like a scrapheap. ’

For three long months Pino was stationed at Chatham waiting for the Shropshire’s refit to be completed, confirming his initial impressions. A massive job was required.

Although Captain JA Collins RAN assumed command on 7 April 1943 and she was commissioned as HMAS Shropshire on 20 April 1943, HMS Shropshire was not formally handed over to the RAN until 25 June 1943. During this period, although they were officially part of the Shropshire crew and slept on board, all of the services were provided in the dockyard, and depending on the stage of the refit and the associated changing basins, at times the crew had to walk several hundred yards for messing and toiletries.14 Hundreds of dockyard workers swarmed the ship which made living conditions uncomfortable and disconcerting. The weather and continual air-raids were also not conducive to a happy crew.15

Pino was assigned to the port of the ship and the usual paint chipping, painting and cleaning was the order of the day as well as never ending training courses (radar, gunnery, damage control and training cruises on other ships), not to mention regular pep talks by Captain Collins as he attempted to keep the crew motivated and occupied. There were visits and addresses by dignitaries such as Stanley Bruce, the Australian High Commissioner and Doctor Evatt, the Australian Minister for External Affairs. Even Lord Haw Haw spoke to the crew, albeit indirectly, when he was heard to say on German radio on 18 May 1943 that the Shropshire would never reach Australia because they knew the departure date.

What did the crew do for these three months? Evidence from Pino’s war diary is very scant during this time but a look through his WWII pictorial collection and his 1985 travel diary17 suggest that although they were kept busy by day, the crew were allowed plenty of leave, both daily after 1600 hours and overnight to relieve their boredom and tensions.

Diary entry early June 1943 – ‘We used to go to London every weekend and go into the town of Chatham every week day; also had six days leave, went to Edinburgh, very nice, seen bridge and Lock Lomond. ’

His postcard collection indicates that Pino certainly saw all of the major sights of London including the ruins caused by the Blitz. Off to Scotland for six days in late April, Pino also witnessed the sights of Edinburgh and the surrounding countryside. Several addresses in his log book also suggest a little female company did not go astray including a Miss A Young of Edinburgh and a Miss C Cliphane of Friarton, Perth.

Pino’s real love however, was not the big cities, rather the local town centres of Chatham and Gillingham. This feeling resurfaced in 1985 when he visited the area including the naval dockyards and of course the many pubs and taverns he frequented during those hours on leave.

Diary entry 20 September 1985 – ‘I was determined to find that little tavern I drank in many years ago, the Prince of Orange and find it I did, but it was finished as a tavern as it had a For Sale sign on it. Inside was the carpenter busy at work but the signage and the building were how I remembered it, still the same, a little older, but still there. It certainly brought back memories and a little tear to my eye.18As I researched this story and immersed myself into my father’s experiences it is about this period of time, maybe late May 1943 that I could sense things were taking a different course for Pino (and possibly other crew members) as the protracted refit just kept on going. Was he homesick? Was the lack of action making him restless? Was he not satisfied or at the very best relieved, to face tedium in his daily routine rather than face the unknown in crossing the Atlantic or Pacific Oceans? Did he expect a repeat of his experiences traversing America? By now Pino’s diary entries were brief and irregular, even his memoirs in later life went no further than returning home with HMAS Shropshire, yet he spent well over two more years in active service.

Was the surreal nature of war one that he now expected?

Short and sharp experiences, taking the good with the bad? Could it have been that Pino’s previous highs could not get any higher and his previous lows not get any lower?

But little did Pino realise that he had one more high awaiting him, one of a very different kind and one that would be associated with the game of cricket!

By late May 1943 it appeared that the Shropshire’s refit was never-ending. It was progressing as best it could but there were continual delays due to problems with the supply of equipment. With no deadline in sight, around early June 1943, an Australian Rules football match was organized between the RAN and RAAF. The result is unknown but it proved a tonic for a lot of lonely Australians in the United Kingdom.19 It was possibly with this backdrop that Chief Petty Officer (Telegraphist) Eric Moran thought of Pino after the idea was raised about the Shropshire forming a cricket team to play against the English.

Eric Moran was one of the more senior members of the small HMS Wolfe draft. Maybe it was during those days as they travelled across America or maybe, as they crossed the Atlantic in order to distract their fear that Eric, Pino and another HMS Wolfe draftee Ron Liddicut shared their mutual passion and recounted their skill and exploits in cricket. Pino was a very talented cricketer, short in stature but fearless and fast with the ball. According to his post-war cricket captain Jack Kios, ‘Pino was a very fast and angry bowler who opened our attack, a better bowler than batsman but still mean and handy with the bat.20

Maybe it was all of those years in Ingham, with his three brothers and their mates, living opposite the railway station with its tracks, yards, platforms and carriages the perfect venue for a game of cricket? This array of improvised pitches and arenas, (along with a tin as a wicket and any piece of wood they could find as a bat) ensured that ‘game was on’ as soon as they got home from school.

…. Our home was situated in Lynch Street right opposite the railway station so most of our free time was spent hanging out on the tracks and carriages. Our cricket pitch was often on the platform or inside the carriages, hiding under the tarpaulins when the station hands came along. Broken windows and being warned off countless times by the police did not deter us. We still returned. As competitive as hell, you could always be assured that each game ended up in arguments and fights but still the next day we would meet our mates for a re-match, mainly because we gave as much back as we received.21

The Livery brothers also played cricket in the local competitions during the early war years before they signed up, although at times it was difficult to put a side together. In those days anyone who could hold a bat managed to make it onto the team. Prior to this the boys played for their school, Ingham State Primary, their arch rival being the local convent school. Their coach, Ivor Middleton, the Grade VI and Scholarship teacher was paradoxically good at using the cane but also clever at challenging the boys, well aware of their competitive nature. Pino recalled how one day at practice he put a two-shilling piece on top of the wicket and dared anyone to knock it off by bowling him. Mickey Pugh’s first ball sent the stumps flying!

On 23 June 1943 Eric Moran accepted an offer and scrambled together a cricket team to play the Harrods team at Lord’s Cricket Ground. The HMAS Shropshire team included both officers and ratings. Captained by Eric and supported by Stoker G Faulkner as Vice-Captain, the side included Lieutenant LS Austin, Sub-Lieutenant JD Irvine, Petty Officers G Aungle, EJ Harkness, and R McLean, Able Seamen PG Livery and AG Mountford and Writer RH Liddicut. Harrods provided the 11th man.

It was only because of Eric’s position and standing (later to be Mentioned in Dispatches) that they were allowed to participate and take leave to go to St John’s Wood. Time was extremely limited. It was the last few days before HMAS Shropshire was officially handed over to the RAN. They were about to sail home via trials at Scapa Flow. Many jobs still had to be urgently done to complete the refit and all hands were on deck in the heavy rain, doing a complete repaint, taking on final supplies and conducting final training exercises to check equipment. 22

Both umpires were provided by Harrods as HMAS Shropshire would not release another crew member.

It was meant to be a fun game and fun it was, particularly for the Shropshire lads. Eric was later told that Harrods had ‘rung in a couple of ex-internationals,23 each playing under an alias. A Mr White was later identified as champion Middlesex and English bowler JM Sims.24 The other ‘ring in’ has yet to be identified. Did they play under an alias so as to disguise their unfair advantage or was it because that even elite cricket players could not be seen to be enjoying themselves during war time? The morale of the country was a high priority and even though cricket was seen as a great morale booster it was a fine balance between sport and war. The match between England and the Dominions played at Lord’s a few weeks later on 2-3 August 1943 was evidence of how important the game of cricket was to England’s soul. 38,000 people viewed this exciting spectacle where 950 runs were scored and 35 wickets fell.25

After the game the Shropshire boys enjoyed a quick meal with their opponents and railed back to Chatham that evening. Poor Ron Liddicut could enjoy no such luxury as he was immediately ordered back to the ship and missed the post-match photo shoot. As for the result, needless to say that the Harrods team easily won. Eric recalled that ‘our chaps knocked up more than 100 runs between them.26 He alone made 29.27