By Colin Randall

Colin is a Committee member, volunteer researcher and tour guide of the Naval Historical Society of Australia with a particular interest in the history of Garden Island. He has researched the northern hill, its gardens and tunnels and the Captain Cook Dock. Colin’s previous paper on The Naval Garden on Garden Island, Sydney (Occasional Paper 69) has been published by the Australian Garden History Society.

Introduction

The first records of a ship’s garden were in the first half of the 14th century by Ibn Batutta, the Muslim Berber Moroccan scholar, who when travelling to China observed “the sailors have their children living on board ship and they cultivate green stuffs, vegetables and ginger in wooden tanks.”

The most reasonable candidates for growing on board were bean sprouts- they grow very fast and are highly nutritious.

It was nearly three centuries before ships coming from the West recognised the ability to grow bean shoots on board ships.

In the 17th Century, it was Dutch ship’s captains who understood the value of fresh greens for the health of their crews on the long voyages to and from the Far East. For example in 1632 on the ship Grel a garden was laid out that provided horse radish, cresses and scurvy grass.

They literally had gardens, established on the ships, in tubs to grow the required vegetables and in some cases citrus trees. The practice was so pervasive that the Dutch ship owners in 1677 forbid the practice as they became concerned that the root systems of some plant/trees were causing damage to the ships.

As an alternative, the Dutch East Indies company better known by its initials, VOC, established gardens ashore at strategic places along the sea route at St Helena in the South Atlantic, The Cape of Good Hope and on Mauritius. By 1661 over 1000 citrus trees had been planted in the VOC farms and gardens at the Cape.

The vegetables and citrus fruit helped fight the dreaded scurvy that caused the death of so many sailors well into the 19th century.

The Royal Navy for its part, over a period of nearly 200 years debated the cause of scurvy, the best anti-scourbotics and how they should be administered. In 1757 the work of James Lind clarified the nature, causes and cure of scurvy.

By the end of the 18th Century the practice of supplying ship’s company with green vegetables and onions along with lime juice being the principal way of combating scurvy.

The practice of on-board ship gardens was not totally abandoned as the example in 1795 aboard the East Indiaman, the “Cirencester” where the captain unable to procure any lime-juice “converted a part of his own apartments into a garden which he managed himself with wonderful success.”

Suffice to say that it became regular practice that if a Royal Navy vessel was to be located at a particular place for any length of time the ship would establish a garden ashore to provide the fresh vegetables so essential to keep the crew healthy.

HMS Sirius, Port Jackson – its ship’s garden

So on 11th February 1788, aboard HMS Sirius in Port Jackson, just 16 days after the establishment of the colony of New South Wales in Sydney Cove, the ship’s log records:-

“Sent an officer and party ashore to the garden island to clear it for a garden for the ship’s company.”

Further references to the establishment of the garden are given by Lieutenant Collins – dated 18th February 1788 refers to “the island where the people of the Sirius were preparing a garden”

So it was, that on this twin hummocked island east of Sydney Cove, a garden was established for the ship’s company of HMS Sirius.

The saddle between the hummocks appeared ideal for the establishment of a garden.

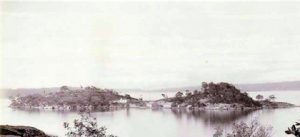

The early photograph below, taken in 1857, looking south, shows the fairly flat area used for the garden.

This garden would over the next 22 years provide fresh vegetables for a succession of Royal Navy vessels that were stationed in Sydney.

The Royal Navy ships which used the garden included; HMS Sirius, Supply (I), Supply (II), Lady Nelson, Porpoise and Buffalo.

The Captain of HMS Lady Nelson, Lieutenant Grant reasserted the use of the garden as evidenced by the Government and General Order published on 8 January 1801 which reads:-

“Garden Island being appropriated as a garden for the “Lady Nelson”, no person is to land there but with Lieutenant Grant’s permission, or the Governor’s in his absence.”

The garden went out of Royal Navy control in 1811 when the new Governor Lieutenant- Colonel Lachlan Macquarie took the island into the Governor’s Domain and used it to raise poultry for the Governor’s table.

Before the coming of the First Fleet.

The Gadigal of the Eora people, knew Garden Island as Booroowang, a fishing place.

The Gadigal had managed their land for over 40,000 years and when the sea levels stabilised around 6000 years ago they managed the land on Booroowang.

While there was no running water on Booroowang the natural sandstone outcrops provides pools and soaks for these resourceful land managers. While there is no record of how the flat area of the garden was used by the aborigines it was no doubt used frequently and for a variety of purposes.

While it is unknown whether yams were cultivated on the flat land, the possibility remains to be established through archaeological investigation using analysis of phytoliths in soil on the site of the original ship’s garden.

It was recorded that the area was relatively clear of growth.

The continued presence and interest by aboriginal people on Booroowang is apparent by the recorded history of them coming to the island.

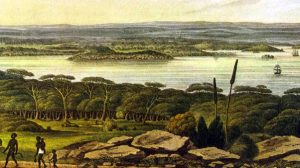

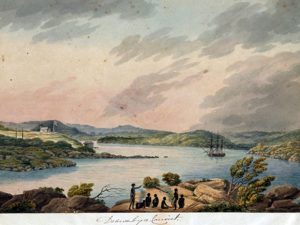

Below is a painting by Joseph Lycett ca 1817-1818 showing aboriginal people on the northern end of Booroowang.

(from ‘Album of original drawings by Captain James Wallis and Joseph Lycett, ca. 1817-1818, bound with ‘An Historical account of the Colony of New South Wales …’, published London, Rudolph Ackermann, 1821) (Mitchell Library)

Interaction between the Aborigines and the Gardeners

Just one week after the start on the garden, a group of 17 aborigines landed on the island. Sighted from on board HMS Sirius they were seen to take some of the tools. Midshipman Mr Hill ordered marines to fire at their legs with buckshot resulting in the dropping of an axe and a pick but with a spade being removed.

Sirius thereafter posted marines ashore on the island to guard the tools and the garden plot.

Some 15 years later in 1803, a group of men were confronted stealing from the ship’s garden.

An aboriginal man, with the mixed group including convicts was shot dead by a marine guard.

The verdict of the coroner was “Justifiable Homicide”.

Sirius’s Ship Garden

The first planting was of corn and onions.

The crop flourished and was picked in July 1788.

To understand the full range of what was grown we need only to refer to the multitude of records including official documents, ship’s log and diaries by those who were involved in this monumental enterprise of sending 1200 people half way around the world to establish a penal colony.

By July 1788 it was recorded the vegetables planted on Norfolk Island included ’turnips, carrots, lettuces, onions, leaks, parsley, celery, five sorts of cabbages, corn, salad, artichokes and beet´.

While in Sydney Cove in 1788 it was recorded that the Reverend Richard Johnson had growing in his kitchen garden “Indian corn, cabbages, turnips, beet, cucumbers, water melons, pumpkins and peas.”

To know what was grown on Garden Island we need to go to the coroner’s record of 1803 into the shooting death of the aboriginal man on Garden Island.

A group of men had been seen plundering the garden. A marine fired on the group of mainly white men resulting in the killing of the aboriginal man.

The 1803 coronial enquiry recorded that when the other men fled the island they left behind a canoe and small fishing boat that contained “maize, melons etcetera.”

Who were the gardeners and the guards?

We know the names of two seaman gardeners and a marine guard, all three from HMS Sirius. This followed a trial conducted on 26 May 1788.

Marine John Atwell and Seaman James Coventry were tried for assaulting and dangerously wounding another Seaman James McNeal. The assault resulted from being intoxicated and quarrelling, the three having consumed a week’s allowance of spirits in one session. Atwell and Coventry were found guilty and each sentenced to receive 500 lashes. As reported by Surgeon John White they did not receive their full sentences as they were weak, both suffering from scurvy.

When HMS Sirius left to go to Norfolk Island in 1789 the garden was not abandoned. In a letter to his mother dated 19 February 1789 Midshipman Daniel Southwell wrote “having left a man to look after a kind of kitchen garden to the service of HMS Sirius.”

HMS Sirius did not return to Sydney as it was wrecked on Norfolk Island but its crew was eventually repatriated to Sydney.

Convicts were also assigned to work alongside the seaman in the garden. The most notable being a 24 year old Jamaican servant, John Caesar who was sentenced to 7 years transportation for stealing the considerable sum of 12 pounds. In June 1789 he was put to work on Garden Island in irons as a result of his troublesome behaviour. Subsequently he was released from his irons, but he then absconded in a canoe having stolen a musket. His is a story of escape, recapture, imprisonment on Norfolk Island, return to Sydney Cove, a small land grant but eventually, a return to theft and robbery.

“Black” Caesar, as he was known, became notorious as the first bushranger. On 15th February 1796 he was shot and killed by a settler near present day Strathfield who claimed the five gallons of rum for his capture.

Water for the gardens

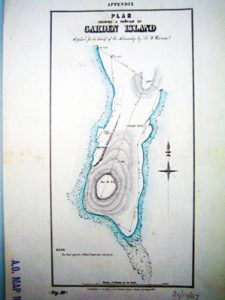

There was no permanent water on the island. The garden footprint was 145 feet (44.2m) by 160 feet (48.8m). There are no records of the digging of a well and no apparent evidence of a well.

However, with the presence of the two sandstone hills, it is possible that with some drainage works, run-off could be directed into a well, while with additional seepage into the well, sufficient water could be collected to maintain the garden.

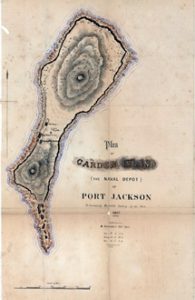

The 1851 survey plan of Garden Island however does show two water tanks on the eastern side of the flat area used for the garden.

Stand-alone ship’s garden, no longer needed

With the departure of HMS Buffalo from Sydney in 1807 the need for a stand-alone ship’s garden was greatly diminished.

Any ship requiring vegetables could easily acquire them from the many Sydney market gardens.

Exact location of the garden

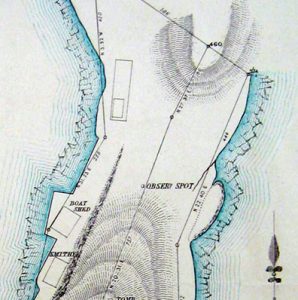

In the middle of what had been the gardens an Observation Spot as part of the Admiralty’s Longitude Studies was established by means of a stone cairn that was marked on the 1851 map.

The location was given as latitude 33 degrees 51 minutes and 45 seconds South and longitude 10 hours 10 minutes and 5 seconds East (152 degrees 31 minutes and 15 seconds East) noting a deviation of 62 degrees 41 minutes South and variation of 10 degrees 10 minutes East.

What happened to the garden?

This is quite clear. It was incorporated, in part, into a lawn tennis court circa 1871. Possibly the first lawn tennis court in Sydney.

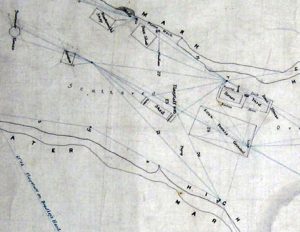

See map below showing Lawn Tennis Ground.

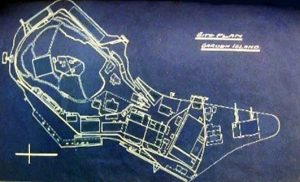

Where is the garden today?

As best as can be identified it is located in the square behind the Clock Tower Building.

Ca 1900 map

Heritage Tours of Garden Island

Garden Island became part of Australia’s naval history just 16 days after the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788, firstly as a ships’ garden. Its naval use further developed into a naval depot near the end of the 19th century and ceased to be an island in 1945.

Many of the buildings are now over 100 years old, each having its own history, but rarely seen by the public unless through a Naval Historical Society tour. Each tour visits the buildings and details of their history are provided by tour guides. Tours start with a video briefing into the Island’s history. Small groups accompanied by a knowledgeable guide then explore the Island.

To undertake a tour contact the tour co-ordinator by E-mail tours@navyhistory.au or by phone (02) 9359 2243 office hours are Tuesday & Thursday.

References:

Torck, Matthew. Maritime Travel and the Question of Provision and Scurvy in a Chinese connection. East Asian Science, Technology and Medicine No. 23 ( 2005)

Frame, TR. The Garden Island. Australian Naval Institute 1990

Rivett, Norman. Our First Gardeners. Naval Historical Review, September 2016

Burnby, J and Bierman, A. The incidence of scurvy at sea and its Treatment. Revue d”Histoire de La Pharmacie. 1996, No. 313 99 339-346