This paper was written by Society volunteer, Commander Martin Linsley RAN Rtd. Its genesis was a list of the RAN participants in the Suez Crisis compiled by Mike Fogarty a former RAN officer and diplomat. Contributions were also received from participants; Commodore Kelvin Gulliver AM RAN Rtd and Captain Nick Bailey RAN Rtd who were served as junior officers in HMS Newfoundland at the time.

One chronicler called it ‘the shortest and silliest war in history’[i], but Operation Musketeer, better known as the 1956 Suez Crisis, signified the end of an era and the beginning of a new world order. The conflict focused on the Egyptian owned Suez Canal, and involving a conspiracy orchestrated by France, the UK and Israel. At least 13 members of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) were involved.[ii]

Following the end of WWII, the RAN maintained close links with the UK’s Royal Navy (RN), its parent service. It was common for RAN members, particularly officers, to be posted to the RN for ‘service, training and promotion courses’. The posting was welcomed by many. It began and ended with a 4/5 week’s sea passage travelling first class on a passenger liner. The overseas allowances were good and RAN personnel were the envy of their RN contemporaries. More than one young officer found his future wife during his time in the UK.

Four other RAN members serving with the RN in 1956 had been commissioned from the ranks. Two of them, Graham (Spider) Currie and Leonard Peterson had been conscripted for service in WWII, after which they were accepted into permanent service and undertook officer and specialist training. By September 1965 SBLT Special Duties (the SD designation first being used that year) Currie was serving as a Communications Officer in HMS Woodbridge Haven, the command/depot ship of a Coastal Minesweeping Group. SBLT SD Peterson was a Boatswain Officer in the aircraft carrier HMS Albion. Fellow SD officers Charles Goodwin and Norman (Bruce) MacRae also undertook their officer training in the UK. SBLT Goodwin’s first sea-posting as an Ordinance Engineer officer was to HMS Tyne, a depot/headquarters ship; and for Communications Officer SBLT MacRae it was to the destroyer HMS Cavendish.

In August 1956 another six Australian officers were on their second or third postings with the RN. LCDR Ian Burnside, a navigation specialist, undertook long-course training during his first posting, and was sent to a destroyer HMS Duchess for his second. Rory Burnett was the Torpedo and Anti-Submarine officer in HMS Jamaica, a light cruiser. Onboard another light cruiser, HMS Ceylon, LEUT Ian Macgregor was the Assistant Gunnery Officer. Aged just 27, he had already served six years in UK. Subsequently, he lost his life in the Melbourne/Voyager collision. LEUT Edmund Melzer was a communications specialist in HMS Woodbbridge Haven assisted by Graham Currie. Donald (Weary) Weil joined the RAN in January 1949 and just eight months later was sent to UK for 3½ years of RN training and service. In March 1956 he was back in UK, and by October he was onboard HMS Bulwark, an aircraft carrier. LEUT Ian Nicholson undertook the RN Long Communications Course in 1954. On completion he was posted to sea and in October 1956 he was serving in the destroyer HMS Daring.

RN service was the first overseas posting for three young Supply Cadet midshipmen; Brian Bigelow, Keith Denton, and Kelvin Gulliver who were 15-year-old classmates when they joined the Naval College in 1953. After initial training they were sent to the UK in 1955 to join their RN contemporaries in the training carrier HMS Triumph for further Cadet training. They were promoted to Midshipman on 1 Jan 1956 and posted to sea for 12 months to complete their sea training. This was followed by Supply specialist training ashore in UK for 16 months before returning to Australia in May 1958. In September 1956, on the outbreak of the Suez crisis, Brian was serving in HMS Eagle an aircraft carrier,Keith in another carrier, HMS Albion, and Kelvin in HMS Newfoundland, a Singapore based light cruiser. In Newfoundland also was Nick Bailey an RN Midshipman who subsequently joined the RAN and became a Captain.

All these British ships were part of the RN’s Mediterranean Fleet for Operation Musketeer. Newfoundlandaccompanied by Diana, Modeste and Crane had been transferred from the Far East Fleet to patrol at the southern end of the Canal. Australia’s then Prime Minister, Robert Menzies, was not supportive of the Australians being onboard RN ships during a conflict in which Australia was not directly involved. While he could do nothing to prevent it, his concerns were evident in the requirement for the 13 Australians to conceal their nationality. This entailed changing the only marks at the time that distinguished their uniforms from the RN by replacing the Australia inscribed brass buttons with RN ones. It is doubtful whether many carried out this direction because of the late notice and that they were in tropical rig or Action Working Dress (AWD).

The Suez Canal, stretching 193.3 km between the Mediterranean and Red Seas, was completed in 1869. It was built by the Suez Canal Company. The enterprise began with mostly French private investors and a significant Egyptian shareholding, but by 1890 it was 44% British owned. The canal slowly became very profitable, but for Britain it had strategic significance because it shortened the time taken for the country to reach India and its eastern colonies.

In response to an anti-European riot in 1882 Britain landed an army, seized the Suez Canal and developed a protectorate over Egypt. After WWII the company’s profits grew rapidly as oil shipments increased. In 1952 developing nationalism in Egypt resulted in a military coup led by Colonel Nasser that overthrew King Farouk. To invigorate Egypt’s economy Nasser undertook to dam the river Nile at Aswan. In 1956 the World Bank denied a loan for the project. To gain the funds necessary for the dam Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal Company in July 1956, promising to fairly compensate its shareholders.

Britain, wishing to retain its influence over the canal and the Middle East, considered Nasser a threat against which it was prepared to use force. So did France, which was fighting an Egyptian-supported rebellion against its rule in Algeria. Israel was also anti-Egypt. Since its formation in 1948 it had consistently and increasingly been harassed by Egypt, including denial of its use of the Suez Canal. Egypt was also sponsoring raids by fedayeen guerillas that resulted in Israeli civilian casualties. While understanding these issues, the USA and other countries opposed the use of force for their resolution.

Five Nations led by Sir Robert Menzies were chosen in September 1956 to negotiate with Nasser. Menzies proposed the “establishment of principles” for the future use of the canal. This was to ensure that it would “continue to be an international waterway operated free of politics or national discrimination and with a secure financial structure and international confidence”. He envisaged that increased confidence would expand Canal use and guarantee a secure future. The proposal also included a convention to recognise Egyptian sovereignty of the Canal, and the establishment of an international body to run it. Nasser rejected these proposals. As Menzies negotiating skills on the international scene were limited, he was unable to reach an understanding with Nasser.

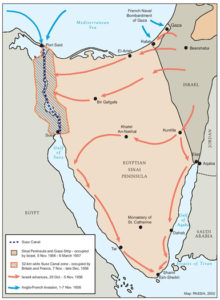

In October 1956 France convened a secret meeting with Britain and Israel. Under the Protocol of Sèvres the parties agreed that Israel would invade the Sinai. Britain and France would then intervene – supposedly to separate the warring Israeli and Egyptian forces – and set a 24-hour deadline for the forces to withdraw 16 kilometres from either side of the Suez Canal. Assuming Egypt would not accept the ultimatum, Britain and France would then argue that Egypt’s control of the Suez Canal was too fragile and that it needed Anglo-French management. A pretext for invasion was set, so too was the start date for invasion.

Originally planned and prepared as an Anglo-French operation for early September 1956, Operation Musketeer had to be delayed because of the need to coordinate with Israel. The Operation had no clear goal beyond seizing the Suez Canal zone by capturing Port Said at the northern end of the waterway, and then moving south.

Since August 1956 the Anglo-French air-sea-ground force had been concentrating in the Eastern Mediterranean, planning and training. It consisted of approximately 45,000 Britons and 34,000 Frenchmen, 200 British and 30 French warships (including seven aircraft carriers), more than 70 merchant vessels, hundreds of landing craft, and 12,000 British and 9,000 French vehicles. One New Zealand vessel, the cruiser HMNZS Royalist was also present, as a carrier group radar picket, ‘but was ordered not to take part in any operations’[iii]. Of this force, only the cruiser HMS Newfoundland and her 3 escort vessels were located south of the canal.

The conflict began on 29 October when Israeli aircraft attacked Egyptian positions throughout the Sinai. Paratroopers were dropped and ground forces headed south and west, routing Egyptian opposition within five days.

On 30 October Britain and France sent the ultimatum to Egypt and Israel. As planned, Israel accepted and, as expected, Egypt rejected it. Egypt’s response was to continue fighting, sink all 40 ships that were then in the Suez Canal and thereby deny the conspirator nations their purpose of keeping the waterway open. Operation Musketeer commenced. On 31 October a land- and carrier-based air strike neutralized much of Egypt’s air forces.

With Egypt having a small and comparatively ineffectual navy, the major roles for the British and French navies were to support and protect an amphibious landing, and to provide aircraft for ground attack. During the night of October 31-November 1 the Anglo-French invasion armada sailed from Malta and Algeria. Shortly after, a smaller force loaded at Cyprus, which was closer.

On the night 31Oct/1 Nov at the southern end of the canal, the cruiser HMS Newfoundland, (a Crown Colony Class light cruiser of 9000 tons, 3 x 6” guns, 14 bofors) encountered and ordered the Egyptian frigate Domiat to “heave to”. Domiat refused and opened fire and caused some damage and casualties with several 4” shells. (1 killed, 5 wounded). Newfoundland and the accompanying destroyer, HMS Diana returned fire and sank the Domiat. (38 killed, 69 Survivors). Domiat was a British built River Class Frigate (1590 tons, 2x QF 4 in /40 Mk.XIX single mounts CP Mk.XXIII) (similar to HMAS Barcoo) and had been sold to the Egyptian Navy in 1948. Midshipman Gulliver’s Action Station in Newfoundland was in the Emergency Crypto team deciphering and transmitting the multitude of highly classified signals. This provided him with a unique insight into the many factors involved in the conduct of the War. Before the commencement of hostilities, he had been working in the Pay Office which suffered a direct hit from the Domiat. Nick Bailey was on the GDP on the Port side of the Bridge and witnessed the whole engagement.

The Australian officers in the ships in the East Mediterranean were involved in supporting activities in their respective ships[iv]. They would have witnessed carrier aircraft and helicopters taking off and landing from their operations against Egypt. They would also have been aware that the British and French ships were being shadowed and harassed by ships of the US 6th Fleet.

World reaction to the attacks, led by the USA, was near immediate and almost uniformly negative. President Eisenhauer was distracted by the forth coming election in USA and John Foster Dulles, the US Secretary of State was completely opposed to it. Lord Mountbatten, the First Sea Lord, had opposed the invasion but reluctantly accepted his Government’s decision. A further distraction was Russia’s brutal invasion of Hungary at that time. On 2 November a United Nations resolution calling for a cease-fire was passed[v]. Only the three conspirators together with Australia and New Zealand voted against it[vi]. Egypt accepted the direction, but the fighting continued regardless.

Early on November 5 British and French paratroopers landed at strategic points surrounding Port Said. Despite spirited resistance, they soon achieved their objectives.

|

|

Musketeer’s amphibious phase began on November 6. Following limited gunfire support and mine-sweeping activities, landing craft and amphibious tracked vehicles left the ships lined-up five miles offshore. Shortly afterwards British commandos left the British carriers Theseus and Ocean for the first helicopter-borne assault landing in history. With Egyptian resistance becoming increasingly disorganized, the attackers won control of Port Said and the area surrounding the northern end of the Suez Canal.

In the afternoon of November 6, the British government succumbed to intense internal, diplomatic and economic pressure and, after advising France, ordered a cease-fire from midnight. By interpreting ‘midnight’ to mean local time. the Anglo/French advance continued for 6 ½ hours, meaning that Musketeer’s ground war came to an end after less than 43 hours. Instead of displacing Nasser and controlling the entire length of the Suez Canal, just a quarter of its length was under Anglo/French control.

Following the cease-fire, British and French forces were to withdraw and Israel was to leave the Sinai. Israel only agreed when the United Nations undertook to employ an Emergency Force to occupy the canal zone as a buffer between itself and Egypt. The evacuation of Anglo-French forces was completed on 22 December when a United Nations Peacekeeping Force, proposed by Lester Pearson (future Prime Minister of Canada), was implemented to patrol the Canal. Under the auspices of the United Nations, a fleet of salvage vessels raised approximately 40 ships sunk by the Egyptians to block navigation in the canal. It was reopened in April 1957.

Although tactically a success, both in the amphibious and airborne assaults, Musketeer proved to the world that Britain and France were no longer superpowers. It left a power vacuum in the Middle East. Only Israel achieved its objectives. It gained access to the Canal when it reopened after five months closure, and a dangerous and hostile neighbor was weakened. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization was also diminished; there was animosity and suspicion between Britain and France and both these countries were displeased with the lack of support from USA.

Egypt and the Soviet Union fared best from the conflict. Nasser emerged as a hero of the Muslim world and Egypt’s ownership of the Suez Canal was affirmed. The Soviet Union was now considered to be friendly to Arab interests and the Canal was opened to its use for the first time since WWI.

British military and RAN participants in Operation Musketeer were awarded the Naval General Service Medal (1915-1962) – clasp Near East. As Australia had not allotted any of its personnel for duty in the Suez Operational Area medal recipients were precluded from repatriation benefits.

It was one of the last occasions that Australian servicemen received combat honours for service in the military operations of another country for which they had not been allotted for duty. Current regulations preclude this practice.

[i] Suez Crisis: Operation Musketeer. Deac WP Military History, accessed April 2001

[ii] The members listed in this article were identified by Mike Fogarty, former RAN officer, diplomat, and historian, through a search of RAN files at the National Archives collection in Melbourne circa 1990. It is unofficial, and more RAN members might have been present.

[iii] Operation Musketeer. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Musketeer_(1956), accessed April 20

[iv] Royal Navy aircraft carriers in which Australian officers were embarked included Eagle, Bulwark and Albion.

[v] The first ever emergency special session of the United Nation’s General Assembly’s convened on 1 November 1956 after Security Council resolutions involving the belligerent parties failed on 30 October. The General Assembly adopted the proposal of the United States calling for: an immediate ceasefire, the withdrawal of all forces behind the armistice lines, and the reopening of the Canal. The resolution was adopted by 64 votes to 5, with 6 abstentions.

[vi] A detailed analysis can be read in Australia, Menzies and Suez. Australian Policymaking in the Middle East Before, During and After the Suez Crisis. Bowker, Dr R. Department of Foreign Affairs & Trade, 2019. It is not commercially available, but can be bought at the National Library of Australia bookshop