By Lieutenant Commander Desmond Woods RAN

This paper was first published by the Australian Naval Institute online and in an abbreviated form the by the UK Naval Review and by US Naval Institute Proceedings. The Society is grateful to Lieutenant Commander Woods for making it available to the Naval Historical Society of Australia.

Lieutenant Commander Woods joined the Royal New Zealand Navy in 1974, subsequently serving in the Royal Navy, the British Army and the RAN as an Education Officer, teaching naval and military history to junior officers. From 2003-2010 he ran the Strategic Studies Course and Naval History induction at the RAN College before joining the staff of the Australian Command and Staff College. He was the Military Support Officer to the Defence Community Organisation in Canberra, worked on the RAN’s International Fleet Review in 2013, was the Staff Officer Centenary of Anzac (Navy) and Chief of Navy’s Research Officer. He is the Navy’s Bereavement Liaison Officer. LCDR Woods is a Councillor of the ANI and is a regular contributor of naval articles and book reviews to Australian and international naval historical journals.

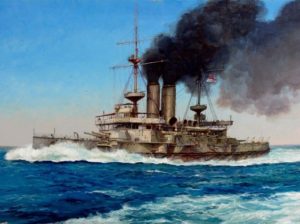

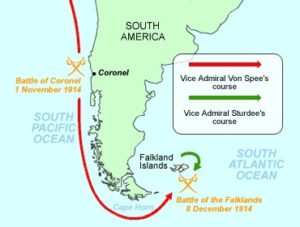

On the morning of 4th November 1914 news reached the Admiralty in Whitehall of the disaster that had overtaken Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock and his cruisers Good Hope and Monmouth at the Battle of Coronel off central Chile on the evening of 1 November. Cradock and all 1660 men of his two outclassed, under gunned and obsolete cruisers had been destroyed – without inflicting any serious damage on Vice Admiral Maximilian’s von Spee’s armoured cruisers SMS Scharnhorst and Gniesenau and his cruiser escorts. These were the ships of the German East Asia Squadron that had crossed the Pacific from their base in China, solved the problems of coaling and supply, and retained their capacity to strike at the Royal Navy’s South Atlantic Squadron with lethal force. Cradock made very clear before leaving Port Stanley to engage von Spee that he did not expect to survive such an encounter but would not attempt to evade it either. He told the Governor of the Falklands, Sir William Allardyce in his last meeting with him that he did not expect to see him again. He handed him a package with his medals and a farewell letter for an Admiral who was a former shipmate. He was well aware that his ships HMS Good Hope and Monmouth were inadequate for the battle he believed he was obliged to fight.

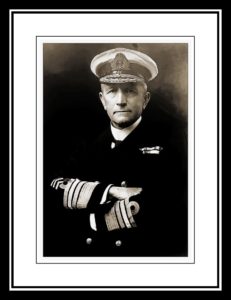

At the Admiralty 4th November was the first day of Admiral Sir John ‘Jacky’ Fisher’s return after taking over from Prince Louis of Battenberg as First Sea Lord. Fisher had built Britain’s modern battle fleet in preparation for war at sea with Germany. From retirement he had watched as his pre-war plans for using his fast, heavily armed battle cruisers to clear the trade routes of the world of commerce raiders had been ignored in favour of retaining these powerful ships in the North Sea awaiting the anticipated day of reckoning with the Kaiser’s High Seas Fleet.

As the scale of the defeat at Coronel and the loss of life became apparent Fisher demanded to know where his battle cruisers, ‘his greyhounds’, as he called them, had been when Cradock was sunk. Specifically, Fisher wanted to know why von Spee’s armoured and light cruisers had not met the fast powerful battle cruisers that he had built to, in his phrase, ‘Eat German cruisers as an armadillo eats ants.’ [i]

The First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, who had recalled the now elderly, but still mentally vigorous Fisher, to office, reacted to the news asking among many other questions how swiftly the most powerful warship in the Pacific, the RAN’s battle cruiser, HMAS Australia would take to get to the Galapagos Islands.[ii] This request for information was ironic because it was the Admiralty which for weeks past had been preventing Admiral Sir George Patey, RN, the RAN’s fleet commander at sea in his flagship, from following his strategically sound instinct to pursue von Spee to South America in Australia.

On the 12th October Patey signalled the Admiralty proposing a route to South America for Australia via the Marquesas and Galapagos Islands to ensure that von Spee was not using either place as a coaling base. On the 14th the Admiralty replied to this request:

It is decided not to send Australian Fleet to South America. Without more definite information it is not desirable to proceed as far as the Marquesas Islands.[iii]

Throughout September and October, as von Spee made his way across the Pacific, Churchill had denied Cradock the powerful reinforcements for which he had asked. Instead he sent him the slow and mechanically unreliable pre dreadnought battleship HMS Canopus. Churchill seriously overestimated her capability. Because she carried four 12 inch guns Churchill post war continued to describe this reserve manned, elderly battleship as, ‘…the citadel around which all our cruisers could find absolute security.’ [iv]

Churchill had been a cavalry officer as a young man and had no personal naval experience. In 1914, despite his years at the Admiralty with professional seamen, he appears to have been inclined to believe that the calibre of a ship’s guns could be used to assess a ship’s total fighting power, regardless of all other factors including her age, her state of manning and general battle readiness. Once Cradock was joined by Canopus he soon discovered that the slow old battleship inhibited rather than enhanced his ability to manoeuvre and fight in the South Atlantic. That was why she was not with him when he faced von Spee’s modern ships at Coronel. That absence probably saved her from destruction.

Had Fisher been deploying the RN’s worldwide fleet from the start of the war — rather than Churchill, Battenberg and the Chief of War Staff at the Admiralty, Vice Admiral Doveton Sturdee — it seems at least possible, that Cradock would have had HMAS Australia as his ‘citadel’ ship when he took on the German armoured cruisers. Had Patey’s timely request to leave his base at Suva and pursue von Spee in his battlecruiser been granted, then the battle off the South American coast, when it came, would not have been a one sided fight which Cradock could neither win nor avoid.

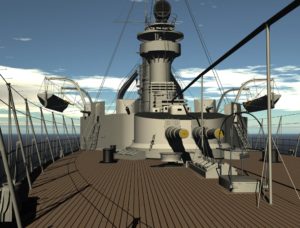

Australia had eight long range 12 inch guns with which to engage the 8.2 inch guns of the two German armoured cruisers. If von Spee had evaded Patey’s pursuit of him across the Pacific, and reached the coast of Chile, then Cradock’s two armoured cruisers, Good Hope, Monmouth and the light cruiser Glasgow could have been supplemented by the fast and powerful Australian battle cruiser. The Germans’ main armament would have been outranged, and Australia’s heavy, armour piercing, 12 inch shells would on the balance of probabilities, have disabled either or both Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. Whatever the outcome of such an engagement in the eastern Pacific, von Spee’s plan to re-supply in Valpariso, round Cape Horn and attack shipping routes in the South Atlantic as he fought his way home to Germany would have been defeated.

Counterfactuals, such as those presented above, are not history, and are necessarily speculative. But it seems reasonable to assume that had Patey and his flagship been released from the central Pacific in good time to pursue von Spee, then the gallant Cradock and his sailors might have survived their battle and the Royal Navy would have avoided its first significant defeat in a sea battle since the war against the United States of 1812.

Why that possible outcome did not happen, and tragedy and disaster ensued for the Royal Navy instead, is the subject of this paper. To provide an historical context for Coronel and the opening months of the war in the Pacific an examination of the pre-war strategic situation is necessary.

The new strategic calculus in the Far East and Pacific in 1913

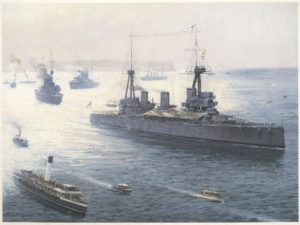

In October 1913 the strategic calculus in the Pacific shifted dramatically in favour of British maritime interests when the Australian Fleet Unit, led by the new battle cruiser Australia, steamed into Sydney harbour. With the flagship were two Chatham class light cruisers: Sydney and Melbourne, built for the RAN; a third older cruiser, Encounter, on loan from the RN; and three new destroyers. Rear Admiral Sir George Patey, RN, relieved Admiral Sir George King-Hall, RN, the last of the Royal Navy’s commanders of the Australian Station. The Australian government had bought and, with the assistance of the parent navy manned, a formidable maritime deterrent. The persistent colonial fear that in wartime Australia would have its ports blockaded or bombarded, and its trade routes raided by the German East Asia Squadron was lessened but not eliminated. Australians rejoiced as they welcomed their new Navy and politicians basked in the reflected glory of this long awaited maritime muscle. In May of 1914 the deterrent power of the guns of the new fleet was augmented by the modern E class submarines AE1 and AE2 with the capacity to attack German ships with torpedoes.

August 1914 in the Pacific

Nine months after the arrival of the Fleet, on the day war was declared, Australia steamed out of Sydney … ‘in all respects ready for battle.’ She would not return until 1919. Admiral Patey and the young RAN were ready for offensive or defensive operations in the Pacific, depending on what von Spee, and the Naval Staff in Berlin were planning for their East Asia Squadron.

In 1911 Berlin had reinforced German East Asia Squadron with two modern armoured cruisers, Scharnhorst and Gniesenau, and several fast light cruisers, and had given this prized command to the aristocrat Count Maximillian von Spee, a respected and seasoned commander and a man of undoubted personal courage and integrity.

Berlin’s Pacific war plan

The German Naval Staff’s war plan was to wage a cruiser war – against trade routes in the South China Sea, to the north of Australia, and in the Indian Ocean. German archives reveal that this was the strategic intention in the years before 1913 and the arrival of the RAN Fleet Unit in Sydney. Berlin’s planners took the view that food and raw materials from Australia and New Zealand were essential to Britain sustaining a long war and that attacking ships on sea lanes of the Empire therefore justified the inherent risks to the commerce raiders of meeting more powerful warships. It was assumed in Whitehall that the German Squadron would operate from its naval base at Tsingtao in northern China. British naval war plans called for Vice Admiral Sir Martyn Jerram, C-in-C China Fleet, based at the British concession Wei Hei Wei, to attack Tsingtao as soon as hostilities were declared.

The RN’s China Fleet War Plan thwarted

When the opportunity came Admiral Jerram was in position to execute the Admiralty’s pre-war plan with his powerful armoured cruiser HMS Minotaur, HMS Hampshire and two modern light cruisers. On the point of carrying out his orders Churchill, supported by Sturdee, signalled Jerram giving him orders to sail south to Hong Kong to join the pre-dreadnought battleship HMS Triumph, which was unmanned and in dry dock. Jerram was furious and wrote to his wife:

All being ready I raised steam and was on the point of weighing anchor to proceed to a line to the south of Tsingtao, my recognised first rendezvous in the war orders submitted by me and approved by the Admiralty. To my horror, I then received a telegram from the Admiralty, dated 30 July to concentrate at Hong Kong, of all places, just over 900 miles from where I wanted to go. I was so upset that I nearly disobeyed the order entirely. I wish now I had done so. [v

The cost of not capturing SMS Emden at Tsingtao

This reversal of plans by the Admiralty was to have profound ramifications, and the rationale for it was never satisfactorily explained after the war by Churchill or his staff. There was no threat, real or imagined, to Hong Kong to justify Jerram being despatched there. Had Jerram been permitted to attack Tsingtao on the declaration of war he would not have caught Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, which were far to the south east in the Caroline Islands, but he would have captured the fleet train and colliers in Tsingtao which instead survived to join von Spee at Pagan in the German Mariana islands in the Western Pacific. It was these ships that fuelled and supplied the German squadron’s odyssey across the Pacific to Chile and kept them battle ready.

Most significantly, Jerram would also in all likelihood have caught Emden and her collier Markomania and sunk or captured them. They were waiting outside Tsingtao for the RN cruisers to raid their port. The destruction of Emden in August would have avoided the later loss of 20 allied merchant ships and their cargos that Emden’s captain Karl von Müller captured or sank in the Indian Ocean. His three months of commerce raiding stopped British shipping from sailing to and from Indian ports. Emden’s destruction would also have prevented von Müller sinking a Russian cruiser, Zemchug, with heavy loss of life, and a French destroyer, Mousquet, at Penang, and the burning of the British oil storage depot in Madras. With Emden stopped before she began her successful cruiser war, Jerram’s China Squadrom could have been available for the main event — the pursuit and bringing to battle of von Spee. In this alternative scenario the Indian Ocean would have been free for the undelayed sailing of the ANZAC convoys through Suez and on to France and the Western Front, their anticipated destination in October 1914.

Instead the moment for a planned attack on Tsingtao was lost; Jerram was ordered south by the Admiralty and Karl von Müller, to his surprise and relief, found that his base was still open to enter, re-supply in, and leave without interference. After coaling and storing he escorted the swiftly converted armed merchant raider Prinz Eitel Frederichand von Spee’s fleet train, including heavily laden colliers, out of Tsingtao, and joined his admiral now at Pagan. Jerram, languishing pointlessly at Hong Kong, had effectively been played out of the war in the Pacific by the Admiralty.

Franz Joseph, Prince von Hohenzollern, the Kaiser’s nephew, serving as Emden’s second torpedo officer, wrote in his memoirs of the surprise that he and his fellow officers felt at their freedom to enter and depart from Tsingtao in these last days of peace and the first days of war:

Only later did we learn that Admiral Jerram had intended to cruise outside Tsingtao and seize any of our ships he encountered. This had always been a possibility. What a rich prize the Royal Navy would have gained as the greater part of our colliers and supply-ships lay in Tsingtao. Happily we had an involuntary ally in Winston Churchill who ordered the British Squadron to assemble in Hong Kong. This bought us time we could not otherwise have enjoyed. [vi]

Patey’s ‘raid’ on Rabaul – 11 August 1914

Von Spee’s signals to his cruisers were heard but were not able to be decoded for their meaning by naval intelligence staff led by Captain Hugh Thring in Navy Office in Melbourne. The code breaker Dr Wheatley could not give Patey the German Squadron’s exact location, but he was told that the signals appeared to be strengthening daily. Navy Office deduced that von Spee was steering south east, and made the reasonable assumption that the squadron could be heading for Rabaul, the main port in German New Guinea.

As a consequence of receiving this intelligence Patey steamed the RAN fleet unit, which included the ill-fated submarine AE1, to Simpsonhafen. He mounted an operation on 11 August to surprise the Germans ships he hoped were there with a night torpedo attack using his three destroyers. Sydney was waiting as their support ship. The blackened destroyers cleared for action and slipped into the anchorage and found nothing. The signal strength intelligence was misleading; the harbour was empty. Von Spee was at still at Pagan, 3000 kilometres to the north, where his fleet was monitoring signals from the German WT station near Rabaul at Bita Paka.

He learned from these signals the unpalatable fact that just six days after the war had been declared the RAN had made a raid on a German port, 3000 km from its base in Sydney. Von Spee now confirmed what he had already appreciated, that there was to be no safe German base for his ships in the South West Pacific. He fully understood that he was opposed by a powerful well balanced Australian task force, capable of swift deployment and which was actively hunting his ships. It must have been a bitter moment for him. On 18 August he acknowledged this reality explicitly when he wrote that the arrival of an RAN battle cruiser in 1913 had made any pre-war plans in Berlin for the squadron operating as commerce raiders on trade routes in the South West Pacific overly ambitious and positively dangerous. His understatement written to his wife read:

The Anglo Australian Squadron has as its flagship Australia, which by itself, is an adversary so much stronger than our squadron that one is bound to avoid it. [vii]

Invidious options for von Spee

On 25 August Von Spee learned that the Japan had declared war on Germany. The powerful Japanese fleet now made the North West Pacific hostile for him. Tsingtao was about to be under siege from Japanese troops and was no longer an option for basing or for resupply. There remained only one realistic course open, he had to cross the Pacific, round Cape Horn and attempt to make his way home against whatever the RAN and the RN could place in his path. He knew it was a dangerous, probably impossible, option, and a logistical nightmare, but it was all he had left to offer his men and his Kaiser. As long as he could stay afloat and keep moving he was effectively a ‘fleet in being’ and could divert RN and RAN ships that were needed elsewhere. That was a role that was worth adopting. But Emden’s Karl von Muller sought and received von Spee’s blessing to undertake cruiser warfare, to slip covertly into the Indian Ocean and to operate as a commerce raider in accordance with German naval staff plans.

Changing Pacific priorities 1913 -14

The Admiralty’s pre-war plan for the Pacific formed part of its world-wide commerce protection effort. Consequently both Admirals Jerram and Patey believed that their first priority was to find and destroy enemy commerce raiding cruisers. But once the war started competing British and Australian government priorities emerged. These included the seizure of German Pacific territories and the silencing of their wireless telegraphy stations by which the naval staff in Berlin could stay in touch with their deployed cruisers.

Churchill and Sturdee therefore changed their priority to the elimination of the WT stations and the seizure of the German colonies across the Pacific. The stated aim was to sever German communications which could aid German warships; the unstated intention was to use the territories as bargaining chips when the war ended. The Australian government was also keen to forestall the possible Japanese seizure of German colonies on Australia’s doorstep, particularly in New Guinea.[viii]

The Samoan Operation – Taking the Kaiser’s Colony

In the event of war the New Zealand Government had volunteered to occupy German Samoa with its troops and take over the WT station in Apia. It was now asked to do so by the Secretary of State for War, Kitchener. Seizing Samoa was deemed by the War Office in London to be: a great and urgent Imperial Service.[ix] The Commonwealth Naval Board was surprised by this request and the Minister of Defence, Senator Millen, accepted in principle provided this did not divert the RAN from the primary task of finding and defeating von Spee’s squadron. He replied to the request saying ‘… it is manifestly undesirable to divert any of the RAN’s warships from their present mission,’[x] and suggesting that the occupation of Samoa could be done with an escort of an armed merchant ship. This was unlikely to be approved in London or Wellington given the risk that such an unprotected vessel might run into any of von Spee’s ships with disastrous consequences for 1385 New Zealanders. In response to his cable Millen received an unequivocal reminder and hastener from London which read: ‘ …. military authorities hope to hear shortly of Australian activity dealing with German possessions in the Pacific Ocean.’

Patey had no choice but to agree to guard the troopships, and assembled at Noumea a powerful escort consisting of his flagship and Melbourne, and the French armoured cruiser Montcalm. He believed the threat to the New Zealand troop convoy from von Spee was real and he also reasoned that if the German squadron was heading for Samoa, to defend the Kaiser’s colony, it could be brought to battle there. On the basis of the knowledge then available it is hard to fault the proposition that the Samoan expedition was the best chance of achieving a favourable encounter with the German ships. It was a reasonable and prudent assumption and in fact only a few weeks premature. Von Spee would head to Samoa in early September once he learned that it had been seized, but by then Patey had been ordered back to Rabaul.

On route to Samoa Patey learnt that the Japanese had entered the war and he was more than ever convinced that von Spee, (who had learned of it by a signal from the German embassy in Tokyo), had no choice but to head for South America where re- supply was guaranteed in nominally neutral, but de facto pro German, Chile. Patey reasoned, rationally, that Von Spee’s way into the Indian Ocean was blocked by Jerram’s fleet and he would have no chance of getting coal supplies there. It could be a logistical trap from which his fuel-hungry coal fired armoured cruisers could not escape. Therefore he had no choice but to keep heading east.

The German Governor of Samoa refused to formally surrender to the New Zealand troops, but wisely offered no resistance to the force that landed on 29 August. Had Patey been permitted to stay at Apia, as he wished, to await von Spee, a battle would have been almost inevitable. But once the Samoan expedition had succeeded the Admiralty reinstated the delayed expedition to be mounted to capture the Bita Paka WT station near Rabaul and to occupy German New Guinea. When first asked his opinion of the New Guinea operation Patey told the Australian Naval Board that: ‘…..wireless stations will have to wait for now.’ After the war Patey, wrote that his intention in going to Samoa was not only to cover the troop convoy but in the hope that:

I might have the opportunity of bringing Admiral von Spee to action, as I felt sure he would be in the vicinity, and I thought that once I had got so far east I might be left free to deal with the German Squadron in my own way. [xi]

Patey’s expectation that he would be given freedom of action as the local flag officer to continue the chase towards South America was overly optimistic. The naval world encompassing the wireless telegraphy revolution, combined with older underseas cable links, meant that Patey, like all other RN flag officers at sea, could receive orders from Whitehall in a maximum of forty eight hours. Consequently admirals became merely the executors of Admiralty orders. The era of independent strategic command was over. The Admiralty became the de facto operational commander and the Australian Naval Board, which could have been more assertive and was closer to the scene, concurred in the decisions made in Whitehall. This was in accordance with the pre 1914 agreement that RAN ships would be commanded operationally from Whitehall in wartime.

Unfortunately during the early months of the Admiralty War Room’s operations its limited and inexperienced staff discovered that it was much easier to assume command of world-wide naval operations, using modern communications, than to actually try and conduct such operations from afar.

The Australian Naval and Military Force – the Battle of Bita Paka

The reinstated original Admiralty order of 6 August now required Patey to escort the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (ANMEF) to Simpsonhafen, the port of Rabaul. It spoke of the removal of the WT station, but also tellingly re-stated that:

All German colonial territories taken would at the conclusion of the war be at the disposal of the Imperial Government for purposes of an ultimate settlement at conclusion of the war. [xii]

Churchill also spoke on other occasions of the German colonies as: ‘…. diplomatic hostages for the liberation of Belgium.’ Maritime strategy in the Pacific was being made subservient to theoretical peace negotiations and possible post-war diplomacy. The admittedly difficult task of locating von Spee, which should have remained an urgent necessity, was now deferred in favour of the capture of another German wireless station at Bita Paka whose usefulness to von Spee was at an end as he proceeded ever further to the east across the Pacific and beyond its range. [xiii]

The German Squadron ‘raids’ Apia in Samoa

Von Spee, having heard of the New Zealand army seizure of German Samoa, diverted from his easterly course across the Pacific, left his fleet train and sailed his warships south to the now occupied colony. He arrived on 14 September hoping to surprise Patey. But Patey had left Apia on 31 August and Australia and the RAN cruisers were back in Simpsonhafen, off Rabaul, supporting the operation to take the Bita Paka wireless telegraphy station. Had Patey’s wish for HMAS Australia to remain at Apia been granted by the Admiralty, we might now be discussing the Battle of Samoa, not the Battle of the Falklands, as being the decisive engagement fought by the German East Asia Squadron in 1914.

Certainly von Spee and his men were keen to fight the Australians. They cleared for action before dawn and entered Apia Harbour at speed to mount a surprise attack on whatever allied warships might be there. They hoped to find an anchored RAN battle cruiser. Instead, like Patey at Rabaul in August, they found the harbour frustratingly empty. Captain Pochhamer, the First Officer of the Gneisenau writing in his memoirs made much of the general disappointment in the squadron that Australia was gone when the Germans arrived. However he also wrote more realistically that Australia’s 12 inch guns: inspired a certain respect. [xiv]

If Australia had been at Apia, and if the Germans had achieved surprise at close range with their excellent gunnery an RAN victory is not certain. However, the probability is that the duty patrolling cruiser and, in daylight hours, the New Zealand lookouts at the WT station, would have provided Patey with the warning he needed to weigh anchor and proceed into battle at an advantageous range of his choosing. Had that occurred the 8.2 inch guns of Scharnhorst and Gneisenau would have been out-ranged.

Under these circumstances the likelihood is that von Spee would have lost ships. Even if he had escaped outright destruction his ammunition supply for his main armament would have been too diminished to allow him to engage in battle again. His chance of getting back to his fleet train for resupply would have been very low. In practice, any encounter with the RAN Squadron off Samoa would have stopped von Spee’s progress across the Pacific towards Valpariso, Cape Horn and the Atlantic.

It was not to be. Once in Apia harbour von Spee sensibly made no attempt to re take the German colony or to shell its wireless telegraphy station, now being operated by New Zealand army signallers. He knew his gunners were going to need every one of their irreplaceable 8.2 inch shells when battle was eventually joined, as he knew it must be one day. The Australian Naval Board, the Admiralty and Patey now knew precisely where the German Squadron was, but their priority was now safe transit of troops to war, not a naval battle.

Emden calls the shots

On 19 September the Admiralty first learned that von Müller and his elusive cruiser Emden was regularly sinking British ships in the Indian Ocean and sending their crews and passengers to India. Battenberg up to this point had made his priority finding the German East Asia Squadron and bringing it to battle. But this menace at large in the Indian Ocean complicated the situation, and the pursuit of the von Spee became of secondary importance. Churchill’s focus shifted to getting Australian and New Zealand troops to the Western Front. The First Lord of the Admiralty personally took charge of the Royal Naval Division’s defence of the port of Antwerp and was not thinking about the Pacific. Meanwhile, the First Sea Lord, Prince Louis of Battenberg, was under daily attack in the press for his German ancestry.

The Admiralty’s attention, and that of the British cabinet and Australian and New Zealand Governments, shifted to the pursuit of Emden which imperilled this strategic objective.

The urgent priority was now to assemble a powerful escort to get the NZEF and AIF Divisions from Wellington to Albany in Western Australia, and then to Egypt and swiftly into the trenches in France to reinforce the British Expeditionary Force.

Understandably, the Australian and New Zealand Governments had no intention of sailing their troops across an ocean known to contain a German raider without a powerful covering force to guard them from a potentially catastrophic attack. Delay inevitably ensued. Churchill, on his return from Belgium, now overrode Battenberg’s objections to this shift of priority away from von Spee to von Müller. The First Sea Lord was forced to concur with Churchill’s view that getting the troops to the Mediterranean was so important that nothing except the certain prospect of fighting enemy ships should delay it.

At the insistence of the New Zealand Government, supported by the Australian Governor General, Sir Ronald Munro Fergusson, Jerram’s flagship the armoured cruiser Minotaur and the Japanese armoured cruiser Ibuki were sent to Wellington to escort the New Zealand troop transports across the Tasman and the Great Australian Bight to Albany.

To achieve this result Patey was stripped of Sydney and Melbourne which, with Minotaur and Ibuki, made up the powerful convoy escort that finally sailed on 1 November from Albany after being delayed since mid September by Emden’s depredations on the British merchant fleet in the Indian Ocean.

Australia was also briefly ordered to escort the troop convoy, and proceeded south on 15 September, only for the orders to be cancelled two days later.

When news of the disaster at Coronel on 1 November reached Fisher in London he detached Minotaur from her duties escorting the convoy and sent her to Capetown at her best speed. Fisher reasoned that it was not impossible that von Spee might continue round the Horn, cross the South Atlantic heading for the German colony of South West Africa and seek refuge in the deep water harbour at Walvis Bay. Based there he could attack the multitude of British ships using the Cape route from India and Australia and New Zealand to Britain. It would be an audacious, but not impossible plan which had to be countered by a sensible defensive strategy.

Emden’s strategic achievement in the Indian Ocean

Von Spee had released Emden at von Müller’s request to engage in cruiser war in the Indian Ocean. Tactically he performed brilliantly, but strategically he did far more. He threatened all British trade in the Indian Ocean and diverted all available allied warships from their alternative task of pursuing the German East Asia Squadron.

Von Spee knew he commanded a ‘fleet in being’. He was at liberty with the only German naval task force outside Europe still able to inflict a significant defeat on the Royal Navy, if luck and circumstances favoured him. Emden’s cruise was a distraction from this obvious but unresolved fact. Emden’s task was to tie down warships in the Indian Ocean which would otherwise have been concentrating on bringing the German Squadron to battle.

On 30 October, when Emden entered Penang harbour by night and torpedoed and sank the Russian cruiser Zemchugand the French destroyer Mousquet, von Müller was fighting precisely as von Spee needed him to be. This was textbook cruiser warfare and spread alarm across the whole of the Indian Ocean. By late October British ships were not sailing from Indiana ports. Commerce was paralysed by the clear and present danger to maritime trade and the sky-high insurance rates for ships operating where Emden might sink them

Nine days after the heavily escorted Anzac Troop Convoy finally sailed from Albany, Emden’s nemesis overtook her in the shape of the convoy escort, Sydney, at the Battle of Cocos.

By then von Müller’s job of holding the world’s attention while von Spee proceeded unhindered across the Pacific was accomplished. He had served his Admiral well and demonstrated with his single light cruiser just how severe the disruption to the Empire’s trade routes could be in a period of six weeks.

If, in August, von Spee had chosen to ignore the coal supply problems which worried him, and taken Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, and his three light cruiser escorts into the Indian Ocean as commerce raiders, before heading for the Cape of Good Hope, the disruption he would have caused would have been serious and lasted longer. He may have been wise logistically not to go west, but it was surely a finely balanced decision. Had he chosen the bolder course of commerce raiding with his entire Squadron and successfully captured the coal he needed, then he had the number of ships and the firepower to have struck a serious blow to the supply lines of the Empire in the opening months of the war.

The threat from Emden to the troops who left Albany and that were to become the Anzacs, was real. We know this to be true because after Emden was wrecked by Sydney’s shell fire and driven aground, von Müller was captured and spoke of how he saw his duties. He was asked by Sydney’s Captain John Glossop, over a shared dinner in his cabin, what he would have done if he had known of the convoy of thirty seven troop ships passing within fifty miles of the Cocos Islands the day he raided the wireless telegraphy station on Direction Island. Von Müller replied that, ‘Emdenwould have shadowed the convoy in darkness and at first light attacked the troop transports with guns and torpedoes until out of ammunition or we were sunk by the escorts, whichever came first.’

Under that entirely possible scenario it seems highly likely that one of more troopships would have been sunk by Emden. Australians and New Zealanders would have died, in perhaps large numbers, without ever seeing Egypt, far less the beaches of Gallipoli. The negative effect on public opinion in the Dominions would have been severe indeed.

Von Spee’s Pacific progress to South America

While von Müller was attracting a massive allied hunt for a single ship in the Indian Ocean von Spee was solving immense logistical difficulties in getting to South America. His German warships were not designed for steaming over such long distances with so many mouths to feed and coal holds to fill. Coal consumption was the over-riding concern and dictated a slow speed. Re-supply was brought to the squadron by neutral American colliers coming from Hawaii. Fresh food and water were also limited.

After being frustrated at Samoa, by Australia’s absence, von Spee visited Bora Bora in the Society Islands. He flew no flags, and greeted the French Chief of Police in English. Gullible French colonists resupplied him with pigs and fruit and bread before an observant and literate native in a canoe pointed out the word Scharnhorst painted over on his stern. France apparently did not send her more observant policemen to the central Pacific. Von Spee paid the helpful French, thanked them for their assistance and sailed on to Tahiti intending to seize the coal stocks he needed. A junior French naval officer, who knew from Samoa’s wireless warning that von Spee was coming, set fire to the island’s coal supplies. Von Spee, silenced the disembarked gun battery from the sloop Zelee that bravely fired on him. He then bombarded Papeete’s marketplace briefly, causing no casualties, before sailing away without French coal and frustrated.[xv]

An elementary ‘Ruse of War’ and its strategic consequences

Knowing he was being observed, and that his position and course would be reported, von Spee sailed north west from Tahiti over the horizon before resuming his easterly course towards Chile. This elementary mariner’s ‘ruse of war’ was later reported to the Admiralty who fell for this trick and concluded, without any corroborating evidence, that von Spee might be heading back into the western Pacific. As a result of this elementary deception Cradock in his old cruisers at the Falklands would wait in vain for the more powerful armoured cruiser HMS Defence, which he believed to have been sent to reinforce him from the Mediterranean. Defence had started her voyage but was stopped at Malta because it was now believed in the Admiralty that von Spee was probably not heading for Cape Horn and the South Atlantic.

The Admiralty did not inform Cradock of this change of plan or the flawed assumptions on which it was based. By the time this ruse had been detected and Defence finally left the Mediterranean it was too late for her to get to the Falklands to join Cradock before he sailed into the Pacific with Canopus.

In October, on Admiralty orders, Patey in Australia was at Fiji conducting pointless patrols, searching for the supposed return of the German ships to the western Pacific south of the Equator. Simultaneously, the Japanese Navy was searching for them north of it. Meanwhile, through October, von Spee continued his slow progress via Easter Island – where he was willingly re-supplied by a British cattle farm manager who had not heard that a war had started – and on to Juan Fernandez. There he fuelled from colliers escorted to him from San Francisco by the light cruiser Leipzig. Now refuelled it was only a short voyage to the ports of Chile and the snow-capped Andes. But before his welcome from the German community in Valpariso would come his crushing defeat of Cradock at Coronel.

HMAS Australia and Patey – a dog tethered to its kennel

While von Spee’s laborious trans-Pacific progress was occurring, Patey continued to patrol off Fiji, and it would not be until 8 November, a week after Coronel had been fought and lost, and Fisher was back at the helm in Whitehall, that the Admiralty finally ordered Australia, with her fast collier, to sail to the Galapagos to be ready to block von Spee’s progress if he turned north.

By then, for nearly two months Patey had been in a state of impotence described by Arthur Jose, the Official Australian War historian, as being: ‘like a dog tethered to his kennel. He made darts into neighbouring waters and was pulled back before any results could be obtained.’[xvi]

Hindsight is a wonderful asset, and it is easy to be wise about what should have been done with its assistance. But two contemporary naval strategists who were in the midst of these events and who deplored what they saw cannot be lightly dismissed. Admiral Jerram, observing events, lamented what he called: ‘……blundering about in the Pacific achieving nothing.’ He wrote to his wife:

The Australian Squadron, were within about 1200 miles of the German cruisers and by Admiralty order footling about with expeditions to New Guinea and Samoa, operations which could not possibly have any effect on the outcome of the war and which might have been undertaken at any slack time later on. Absolutely contrary to all principles of naval warfare, as in the first place, they were extremely dangerous due to the near presence of a powerful cruiser force and, in the second, they gave time for the enemy to collect coal stores etc. [xvii]

Captain Hugh Thring, who had prepared the RAN for war, and was the most experienced Pacific planner and maritime strategist in Australia, called the Samoan Expedition: ‘…..futile and a waste of precious weeks.’ Thring in Melbourne provided the Admiralty with the decrypted information which continually indicated that Von Spee was moving eastward and was not returning to the South Pacific. The Admiralty used the highly successful decoding skills of Thring’s German speaking linguist Dr Frederick Wheatley but refused to trust the evidence that von Spee was heading for Chile he was producing for them.

What might have been had HMAS Australia joined Cradock before Coronel

There are clear alternative possibilities for HMAS Australia’s movements which were being urged by Patey. Were they feasible? If released at the beginning of September, Australia, perhaps accompanied by either Sydney or Melbourne,might have joined Cradock at the Falklands. The RAN ships could have taken the southerly great circle route into high latitudes round the Horn to minimise the distance into the South Atlantic. Patey kept with him at all times a fast collier, the SS Mallina and supply ships to accompany Australia into the South Atlantic. He and his officers were waiting to be sent east and hoping to bring von Spee to battle before, as they imagined, a powerful RN hunting squadron in the South Atlantic forestalled them.

Alternatively Australia could have travelled a shorter distance and been directed by the Admiralty to meet Cradock’s ships off Chile and together the reinforced squadron would have waited for von Spee’s inevitable arrival in the waters off Valpariso.

It was not to be. Like Jerram, sent pointlessly to Hong Kong in August when he wanted to be dealing with Emden and von Spee’s fleet train in Tsingtao, Patey had been played out of the game by the Admiralty. The last opportunity to bring von Spee to battle in the Pacific on advantageous terms had been frittered away. Consequently, the understrength and outclassed Royal Navy South Atlantic Squadron were defeated at sea at Coronel. Two cruisers were sunk, sixteen hundred British sailors were dead. The British public was appalled and enraged and the newspapers were demanding accountability and swift revenge.

Fisher now took charge and ordered Jellicoe, commanding the Grand Fleet to detach Australia’s two half sisters, Invincible and Inflexible, from the battle cruiser squadron at Rosyth, Fisher placed them under the command of Admiral Doveton Sturdee, (whom he wanted out of the Admiralty for personal reasons), to steam south and take their revenge on von Spee. Churchill had to be convinced that two battlecruisers were needed to take on Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. He was concerned about weakening the Battle Cruiser force in the North Sea.

On Fisher’s orders the new battle cruiser Princess Royal was sent to the Caribbean in case von Spee had plans to use the Panama Canal to return to the Atlantic.

Simultaneously Fisher ordered Patey to take Australia at her best speed and to block the Pacific entrance to the canal in case von Spee had plans to go north from Chile and use the canal to return to Europe. With the old Sea Lord back in charge serious strategic thought was being given to all logical possibilities open to von Spee in the Pacific. Fisher’s doctrine had always been: ‘destroy opposition wherever it presents itself with overwhelming force.’

None of this belated activity could undo the damage done by weeks of dithering and lack of attention to what von Spee was most likely to be doing. This failure by the Admiralty to make good use of time was noted by one keen observer based in Australia, the Governor General of Australia and Commander in Chief, Sir Ronald Munro Fergusson

The climax of the ‘long bungle in the Pacific’

On the 15 November having learned of the scale of the defeat at Coronel, Fergusson wrote to the British Government in trenchant terms outlining Australian views on what he called ‘the long bungle in the Pacific’. He spelt out very clearly the scale of the lost opportunity to use the RAN for the purpose for which it had been built. He wrote:

While reluctant to concern myself with naval strategy I have to report a prevailing opinion that the loss of our cruisers off the Chilean coast is the climax of a long bungle in the Pacific. The maxim of seeking out the enemy’s ships and destroying them has been ignored. Nearly a month was wasted over Samoa; after the wireless station at Simsonhafen has been destroyed the Australia was detained for many days at the Bismarck Archipelago; lastly valuable time was lost cruising around Fiji. Had Admiral Patey immediately destroyed the German wireless station and then sought out the enemy’s ships, these would not have been left unmolested for three months nor, in all probability would our military expedition to Europe have been so seriously delayed.

Admiral Patey at our interview in Sydney on August 2nd was insistent on the need for an immediate and unremitting chase of the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, and I know that he never swerved from that view. There is but one opinion here, viz., that HMA Fleet, and the China Squadron also, has been singularly ineffective; and that to the remoteness of Admiralty control may be traced the concentration of German ships off Chile with its lamentable results. [xviii]

Jose quotes an unnamed post war German naval historian who saw the situation in a similar way. He criticised the Admiralty’s strategy as being disjointed and unduly hampered by the expeditions to Samoa and New Guinea before concerted measures were taken to find and fight the German Squadron. Tellingly this German historian is quoted by Jose as writing…. ‘the mere sending of the Australia to the west coast of South America might have averted the disaster for the British at Coronel.’ [xix]

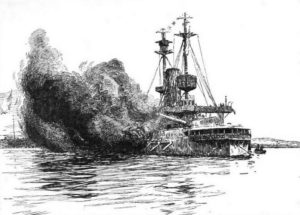

Disaster averted at Port Stanley

Inflexible and Invincible arrived at the Falklands only one day before von Spee did so. Both ships were coaling with their hatches open and not ready for battle. Had von Spee closed the range and opened fire on them he might have achieved strategic surprise. What saved the situation was the elderly Canopus which had been beached as a guardship on Fisher’s orders to protect the entrance to Port Stanley. Her 12 inch guns were fired remotely from the shore and though no hits were scored they came close to Gneisenau and deterred von Spee from attempting his plan to take the Falklands, burn its coal stocks, and capture its Governor. He had seen the masts of the two British battle cruisers in the port and decided to try to outrun them. It was a fatal mistake. Inflexible and Invincible with their cruisers had all day in which to leave the port, overhaul the Germans and eventually destroy them. They did this with the same type of 12 inch guns that HMAS Australia carried.

HMAS Australia after Coronel – the nearest point of contact

After the Battle of the Falklands and the destruction of the German Squadron by Inflexible and Invincible, Australiawas ordered to sail to the United Kingdom via Cape Horn as the Panama Canal was temporarily closed. Over the location of the Battle of Coronel the flagship stopped and a funeral service was held for Cradock and his RN sailors who lay below on the seabed with their ships.

Later that month, after rounding Cape Horn, as the flagship steamed through the waters off the Falklands where Fisher’s other two ‘greyhounds’ had avenged Cradock, Australia stopped to pick up a souvenir of the battle spotted by the officer of the watch. It was a life buoy with the word Scharnhorst on it. It was taken to Patey to examine. That life buoy was the closest that Fisher’s antipodean ‘greyhound’, HMAS Australia, got to the enemy that she had been designed and bought to counter in the Pacific and bring to battle. Admiral Patey and his ship’s company must have been above the wrecks of the East Asia Squadron’s ships containing the bodies of Vice Admiral Maximillian von Spee, his two sons, and nearly 2200 German sailors. These men had joined Rear Admiral Christopher Cradock and his 1660 Royal Navy sailors on the sea bed of the Southern Ocean.

Conclusion and unanswerable questions

Could it have all been different? Could Australia and the very able Sir George Patey have found and engaged Scharnhorst and Gneisenau if he had been given the tactical autonomy he asked for? If he had remained at Samoa when he asked to do so would there be an engagement known as the Battle of Apia? Could a better strategic understanding of the Pacific, a realistic appreciation in the Admiralty and careful following of the intelligence have given Australia the only chance she would ever have to engage an enemy battle squadron? Would she have prevailed in battle against the two German armoured cruisers? Had Australia been with Cradock off Chile would he and his 1654 men in their underarmed ships Good Hope and Monmouth have survived the battle?

Questions about why Australia was not employed for the purpose for which she was built were asked at the time and have been asked for a century, and we are no closer to knowing the answer and nor will we ever be. The answers are unknowable, lost to us like the brave men on both sides who fought the war at sea in the southern oceans in 1914 and paid with their lives for their dedication to doing their duty as professional naval officers and sailors.

END NOTES

- Fisher quote. In regard to cruisers, no number of smaller type of cruisers can cope with even one thoroughly powerful first-class armoured cruiser. An infinite number of ants would not be equal to one armadillo! The armadillo would eat them up one after the other. http://dreadnoughtproject.org/tfs/index.php/

- Pitt, Barrie, Coronel and the Falklands p 43

- Jose, A.W, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918 p 123

- Churchill, Winston. The World Crisis,. Odhams Press, London 1938 p. 370

- Jerram Private papers, letter to wife Clara, Nov 1914, GB 00064, quoted in Carlton. M, First Victory 1914 p 83.

- Hohenzollern-Emden, Prince Franz Joseph, Emden: The Last Cruise of the Chivalrous Raider, 1914 p 32.

- Jose, A.W, p 31.

- The Australian view of the Anglo Japanese alliance was very different from that of the Imperial government.Before the Battle of Tsushima Australians viewed Japan with suspicion. After that 1905 victory many Australians viewed the Japanese navy with alarm.

- Jose, A.W, p 47 Cable from British Government Committee of Imperial to the Commonwealth Government 6 August.

- Ibid p. 49

- Carton, M, First Victory p.94.

- Jose, A.W p 47. In the early weeks of the war a negotiated conclusion to the hostilities was anticipated in London and the future of Germany’s overseas colonies was seen by HMG as a part of the negotiations for a European settlement.

- Bita Paka WT station was duly taken on 11 September with the loss of one RN officer, five Australian sailors, an Australian Army doctor, one German regular and approximately thirty native German irregular police

- Pochhammer, Kapitan zur See Hans, Before Jutland: Admiral von Spee’s Last Voyage, p 212.

- The French navy court martialled the officer in Toulon for losing his gun boat before later decorating him posthumously for his bravery.

- Jose, A,W. p 123

- Jerram: Private Papers, GB 0064 JRM quoted in Carlton p 171

- Jose, A.W p 110.

- Ibid p 47.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bean, C. E.W. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-18 University of Queensland, 1921 Vol IX: The Royal Australian Navy 1914-1918 and Vol X; The Australians at Rabaul

Carlton, Mike. First Victory 1914- HMAS Sydney’s Hunt for The German Raider Emden, William Heineman, Australia, 2013

Churchill, Winston. The World Crisis, 1911 -1918. Odhams Press, London, 1938

Corbett, Sir Julian, Naval Operations, Vol 1, Longmans, Green & Co. London, 1920.

Gilbert, Gregory. Steaming to War: HMAS Australia (I) in August 1914 – AWM Wartime Magazine 2014.

Massie, Robert K. Castles of Steel Britain Germany and the winning of the Great War at Sea, Random House, 2003

Mackay, Ruddock F. Fisher of Kilverstone. London: Clarendon Press. 1973.

Overlack, Peter. The Commander in crisis. Graf Spee and the German East Asian Cruiser Squadron in 1914’, in J. Reeve & D. Stevens (Eds) The Face of Naval Battle. The human experience of modern war at sea. Sydney, Allen & Unwin, 2003.

Pitt, Barrie, Coronel and the Falklands, Cassell & Co, 1960.

Pochhammer, Kapitan zur See Hans, Before Jutland: Admiral von Spee’s Last Voyage, Jarrolds, London, 1931.

Hough, Richard, The pursuit of Admiral van Spee, George Allen & Unwin, London, 1969.

Hohenzollern-Emden, Prince Franz Joseph, Emden: The Last Cruise of the Chivalrous Raider, 1914, Lyon Publishing International, London 1989.

Jose, A.W, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918.

Stevens D and Reeve J, Southern Trident. Strategy, History and the Rise of Australian Naval Power Sydney Allen and Unwin, 2001.

Stevens, D, In All Respects Ready – The RAN in World War 1, Oxford 2014.

Stevens, D, From Offspring to Independence, in Dreadnought to Daring. Seaforth 2012.