- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, Naval technology, Naval history, Influential People, Biographies

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2012 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Chris Clark

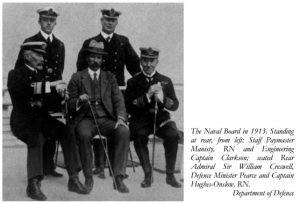

When Engineer Rear-Admiral Sir William Clarkson retired from the Royal Australian Navy on 1 November 1922 with the honorary rank of Vice-Admiral, it brought to a close a 38-year naval career in Australia which was both extraordinary and unique. The last seventeen years of his service had been spent as the Navy’s senior engineer. Eleven of those years were as Third Naval Member on the Naval Board of Administration, including the crucial period of the First World War (1914-18), with responsibility for construction and engineering of RAN ships, ship repairs, and control of naval dockyards and bases. The enormous influence and authority that he wielded across the whole of the nation’s maritime affairs represented a remarkable tribute to his personal qualities, as much as to his professional standing and attainments.

The start of Clarkson’s career promised nothing of his future rise. The first fifteen years were spent in the restricted and stultifying atmosphere of the South Australian Naval Force (SANF), where he was the engineer in the colony’s sole warship, the 960-ton ‘cruiser’ (gunboat) Protector, with additional responsibility for maintaining the technical viability of Adelaide’s deteriorating torpedo and mine defences. He had accepted appointment to the SANF while working as a 25-year-old marine engineer in shipyards at Newcastle upon Tyne, essentially to escape the dismal weather of northern England which was affecting his health, rather than for any ambitions of pursuing a glittering naval career. At Adelaide his chief preoccupations were with maintaining the seaworthiness of Protector amid tight and often shrinking financial constraints, while dodging the periodic bouts of retrenchment which governments inflicted on the SANF.

From Clarkson’s days in South Australia there was at least the compensation – in a professional sense – of becoming associated with an ex-RN officer named William Creswell, who joined Protector in 1885, a year after himself. While Clarkson seemingly stayed aloof from the writing campaign upon which Creswell embarked from 1886 to promote debate over naval aspects of Australia’s defence requirements, the two men appear to have known and respected each other’s abilities and qualities. This became of special significance in August 1900, when Protector went to China under Creswell’s command to join the international force assembled to deal with the nationalist uprising known as the Boxer Rebellion. In the course of a five-month deployment, the ship steamed over 16,000 nautical miles without developing any defects requiring repair. Creswell, more than anyone else, would have appreciated what this flawless performance said about Clarkson’s technical competence and skill as Chief Engineer.

The advent of Federation in January 1901, just as Protector was returning from China, initially heralded little change for Clarkson, or Creswell for that matter. Not until February 1904 was a commanding officer appointed for the Commonwealth Naval Forces, and although this post went to Captain Creswell it was not until October that he was transferred to the temporary national capital of Melbourne to begin setting up a naval headquarters. In January 1905 the Naval Board was brought into being; later that year Clarkson found himself brought into the gathering centre of naval administration when he was posted to Victoria and appointed Fleet Engineer on 1 October, with promotion to Engineer Commander.

It was almost certainly Clarkson’s personal association with Creswell which saw him brought on to a special committee formed in September 1906, to comment on a report on Australian defence that had been prepared by the Committee of Imperial Defence in London. The CID’s report found little need for the local naval forces, and also sought to scotch Creswell’s ambitions of forming a blue-water navy for Australia. Creswell was determined to offer an alternative point of view, knowing that the Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin, was personally in favour of creating a proper navy. The report that Creswell’s committee produced formed the basis for the naval scheme which Deakin announced in Parliament later that month.

Much of the next five years was spent by Clarkson in and out of Australia. Most of his time abroad was spent in England, in connection with the protracted business of deciding the design of the first ships that would bring Australia’s new navy into being, calling for tenders for the construction of these, assessing the tenders and awarding contracts, then maintaining supervision and inspection roles during the construction phase. An additional complexity to this process was the decision of the Australian government to undertake construction of some of the new vessels in Australian shipyards, to lay the basis for a local shipbuilding industry.

An additional cause for Clarkson’s absences overseas came from plans to set up a Small Arms Factory for defence purposes, which the government decided to build at Lithgow in New South Wales. At first, his role was simply to make arrangements for purchasing the machinery to be operated at the new factory, but in the absence of any other suitably qualified local individuals, by mid 1908 he found his name also under consideration for appointment as manager of the new facility. By the time he returned to Australia in mid-1911, having been promoted to Engineer Captain a year earlier, he had dual duties waiting for him: to take up the role of Third Naval Member on the reorganised and expanded Naval Board, and to become acting manager of the Small Arms Factory. His responsibilities at Lithgow extended for another year, until the factory was formally opened in June 1912, and he relinquished control in August.

Extraction from one onerous commitment freed Clarkson up to deal with the variety of complex matters associated with bringing a complete naval organization into existence. The scale of the enterprise was like nothing experienced in Australia before, and now truly merited the formal grant of the ‘Royal’ prefix to the Australian Navy in October 1911. Important issues regularly confronted the Naval Board, such as establishing bases, training facilities, and dockyards for the ongoing construction work on new ships. Many of these matters generated friction and acrimony within the Naval Board, and it was in this period that Clarkson’s friendship and professional relationship with Creswell, as First Naval Member and Chief of the Naval Staff, holding the rank of Rear Admiral and knighted, now came under serious strain.

The start of the First World War in 1914 very quickly added a whole new level of strain and complexity onto the RAN’s administration, much (perhaps most) of it falling within Clarkson’s sphere of responsibility. Since the RAN’s ships and seagoing personnel were placed under the control of the Admiralty in London, the Naval Board as a whole was left with little in the way of a war to fight. The Third Naval Member, however, still had plenty to do, seeing through to completion a range of ship construction projects already underway or about to start. Additional responsibilities also now came his way, beginning with assembling and preparing the ships needed to transport the two expeditionary forces which Australia undertook to raise and dispatch to New Guinea and Europe. All this work was conducted by a committee called the Naval Transport Board which Clarkson chaired under the title of Director of Transports. The increased importance attached to his role received due recognition in April 1916, when he was promoted to Rear-Admiral.

The problems being experienced in Australia with the reduced availability of shipping with which to meet wartime requirements and at the same time maintain normal and essential economic activity led to other arrangements as well. During 1917 Clarkson became head of a board to control Australia’s maritime trade, culminating the next year in his appointment as Controller of Shipping and also chairman of an Interstate Central Committee. After the Australian government attempted to fill the shipping gap by establishing its own line, he found himself also appointed to chair a Commonwealth Shipping Board to supervise the allocation of cargo. So important had all this work become in national, rather than strictly naval, terms that Clarkson was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) in March 1918.

The end of the war in November 1918 did not end the multifarious calls being made on Clarkson’s services. As Controller of Shipping he remained the government’s principal adviser on all shipping matters, both overseas and interstate, even after the Commonwealth Shipping Board ceased to operate in January 1919. Because the lack of shipping was having such a huge impact on Australia’s coalmining industry, the admiral found himself appointed by the government as Chairman of Control of a new committee to manage the coal industry in the face of a wave of industrial strife. Not until the following year was Clarkson able to step away from this role in the national arena and refocus his attention on activities of the Naval Board and the post-war problems of the RAN. Even then Clarkson found himself dragged in during 1921 to give evidence at a Royal Commission inquiring into administration and practices at the Cockatoo Island Dockyard in Sydney Harbour.

By 1922 the Australian defence services came under overwhelming pressure from the government to find savings in expenditure, a course which, although dictated primarily by general economic conditions, had additionally become fashionable with naval disarmament talks underway in Washington. The personnel costs of the services came in for a savage program of retrenchments, particularly among the permanent staff of the military forces but to a lesser extent within Navy also. Notwithstanding an evident desire by the Naval Board to retain its engineers, it was probably inevitable that Clarkson – being close to retirement age anyhow -would be caught up in this bout of economy. It was in this context that his naval career finally came to an end on 1 November 1922.

Despite formally leaving the RAN, this was not end of Clarkson’s utility as a technical adviser to the Commonwealth on maritime matters. During 1923 he was asked to provide a report for the Department of Home and Territories into the feasibility of establishing a port and railway terminus on the western side of the Gulf of Carpentaria, to open the way for faster development of the Northern Territory. No sooner had he finished this task, he was invited to become one of three directors of a new Commonwealth Shipping Board, charged with running the government’s line on a more commercial and business-like basis, and also take control of the trouble-plagued Cockatoo Island Dockyard which was still under government management.

Involvement with the CSB would keep Clarkson busy for the next four years, until the government of S. M. Bruce finally took steps to sell the Commonwealth Line to private operators in 1928. Even this, however, was not the end of Australia’s need for Clarkson’s expertise. In December 1929, less than two months after elections had brought the Labor government of J. H. Scullin to office, Clarkson was asked to investigate and advise on the technical aspects of establishing a Commonwealth steamer ferry service between Tasmania and Victoria. The report which he submitted in January 1930 was effectively his last major contribution to public life in Australia.

Four years later to the month, on 21 January 1934, Clarkson died in Sydney of heart disease. Vice Admiral Sir William Creswell had died in Melbourne just nine months earlier. It was fitting in many respects that Clarkson had outlasted the man whose career in the RAN had been a close parallel to his own. Creswell, made a Rear Admiral and first knighted in 1911, retired in 1919. Clarkson, who was promoted Rear Admiral in 1916 and knighted two years later, followed him onto the retired list in 1922, the year in which both were granted the honorary rank of Vice Admiral. Now these two giants of the early RAN had passed from the scene more or less together.

If Creswell could be said to have provided the seminal drive which resulted in the RAN’s birth, then Clarkson had been the practical midwife who attended to the essential details involved in bringing the force into being. His contribution was, in every sense, as necessary and valuable as Creswell’s, and he also deserves to be regarded as one of the founders of Australia’s proud naval service. The fact that he was, throughout the period of his greatest achievement, the Navy’s senior technical officer demonstrates better than anything else the importance of the Engineering Branch in the RAN’s first decade.

Note: Dr Christopher Clark is the author of Without Peer which provides a biography of Vice Admiral Clarkson. This was produced in 2002 by Australian Scholarly Publishing of Melbourne for the Warren Centre for Advanced Engineering.