- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- History - general

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2020 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Walter Burroughs

The Palm Islands and Challenger Bay affords a large sheltered deep-water anchorage, the last such facility on Australia’s east coast before reaching the northern extremity of the continent. This was found to be of strategic value to the Royal Australian Navy during both World Wars but since then there appears to have been little or no naval interest. This article explores a naval connection with the Palm Islands.

In total sixteen islands make up the Palm Island Group, located about 65 km northeast of Townsville and about mid-point inside the Great Barrier Reef. The largest, with the main settlement, is Great Palm Island; others of significant size are Curacoa, Fantome and Orpheus Islands These days they can be reached by taking a 20 minute flight or 45 minute fast ferry from the mainland. Orpheus Island is now part of a national park, James Cook University operates a small maritime research station here, and there is an exclusive luxury resort on the island which is privately owned.

The naming of this small group of islands comes from a noble vintage. Cook’s journals tell us that on 07 June 1770 after passing through the Whitsunday Passage in HM Barque Endeavour an islet was observed on which it was thought coconut palms could be seen, a valuable source of sustenance. A party of senior men comprising Hicks, Banks and Solander was landed only to find cabbage palms. Hence, the name Palm Islands was arrived at by virtue of mistaken identity.

Further information is provided in Banks’ Endeavour Journal: At noon the islands had mended their appearance and people were seen upon them; the Main as barren as ever with several fires upon it, one vastly large. After dinner an appearance very much like coconut trees tempted us to hoist out a boat and go ashore, where we found our supposed coconut trees to be no more than bad cabbage trees.

Later naval attention appears sparse with Phillip Parker King in HMS Mermaid landing on Palm Island on 18 June 1813, noting the presence of native huts and two canoes. In 1839 John Lort Stokes in HMS Beagle (who does not appear to have landed) noted a number of fires which inferred a local population and fertile soil. In June 1848 Captain Own Stanley in HMS Rattlesnake reported an affray between sandalwood traders from the cutter Will o’the Wisp and natives of Palm Island, where the ship’s crew came under attack and responded by shooting several locals. By the mid-1850s further conflict occurred between an expanding European population occupying native lands, leading to an unattractive period of racial tension and a marked decline in the native population. These islands were the target of recruitment agents seeking labour for bêche-de-mer and pearling enterprises. In 1883 nine islanders were kidnapped by a recruiter and taken to the United States to become part of the Barnum & Bailey Circus.

Challenger Bay and Curacoa, Fantome and Orpheus Islands

All the above names are associated with Royal Navy ships and the three named islands together with Great Palm Island help form the boundaries of Challenger Bay.

The steam-assisted corvette HMS Challenger was flagship of the Australian Station from 1866 to 1870 but she is more famously known for her global marine research expedition from 1872 to 1876. Many places are named after her with the more recent space missions bearing testimony to her fame.

The wooden screw frigate HMS Curacoa was flagship of the Australian Station from April 1863 to May 1866. She is mainly remembered in landing reinforcements for a Naval Brigade involved in the 1863 New Zealand (Maori) Wars. Curacoa Island is now uninhabited.

The sloop HMS Fantome formed part of a three ship Royal Navy Australian Squadron. Under command of John Henn Gennys she was a popular vessel which spent five years in Australian waters from 1851. The Rockhampton Morning Bulletin of 03 July 1929 published a comprehensive article of local names which states: Fantome Island is named after the 12-gun sloop which in the 1850s was closely identified with Australian pioneering exploration.

Orpheus Island recalls the loss of HMS Orpheus when entering Manukau Harbour (NZ) on 07 February 1863 with the loss of 190 lives. Orpheus Island was named by Lieutenant G.E. Richards, RN who commanded the Queensland Colonial Ship Paluma when she was engaged in survey work of the Great Barrier Reef.

First World War

At the time of the First World War the Palm Islands, which are within the protection of the Barrier Reef, were considered safe from enemy attack and afforded a good fleet anchorage. Accordingly, they were used a rendezvous point by ships of the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (ANMEF) when on their way north to German New Guinea.

By way of explaining the importance of these islands Rear Admiral Claude Cumberiege (NHR September 2018) when serving in command of HMAS Warrego says: ‘In June 1914 the Admiral (Vice Admiral Sir George Patey) took his fleet on training exercises to Queensland and later made Palm Islands, then uninhabited, the local headquarters.’ Cumberiege appears misinformed regarding the lack of inhabitants as there is a 1912 report of a visit to Palm Island by the Chief Protector of Aboriginals which says a small aboriginal settlement existed, thought to number about 50 persons. It is likely that the native population melted away with the incursion of naval landing parties and, as the land was now covered with dense bush, with a smaller population the primitive agricultural method of burning vegetation may have ceased.

From the Official War Histories we learn that the cruiser HMAS Sydney met the recently converted armed merchant cruiser and troopship HMAS Berrima off Sandy Cape on 22 August 1914 and escorted her to Palm Island where they arrived on 24 August. Here Sydney handed over escort responsibility to the light cruiser HMAS Encounter which had arrived the previous day. Sydney then made for Townsville to take on provisions before returning on 26 August. The storeship Aorangi arrived at Palm Island on 30 August and lastly the submarines AE1 and AE2 briefly made the island. Later, on 2 September the three cruisers and submarines and the storeship left for Port Moresby, where they took in coal and stores to serve them through the expeditionary period.

There is an interesting narrative by Able Seaman Angus Hermon Worthington1 from the South Australian Naval Brigade who along with 80 others from his state had volunteered to join the naval contingent of the ANMEF. This tells of the only military training received at Palm Island before entering enemy territory.

After anchoring astern of Encounter boats were lowered and parties sent inshore to find suitable landing places. The island is surrounded by a coral reef and the bay swarming with sharks. On the next morning a half-battalion fully equipped was ordered ashore in 12 boats for exercises chasing an imaginary enemy up hill and down dale, through grass and scrub. At noon we stopped for lunch of bully beef topped off with oysters found on rocks, after which we ate bread and jam, washed down by hot tea. Then it was back to practice field manoeuvres. At 4 pm the exercise was called off and by 6.30 pm we were back on board tucking into tea. The other half-battalion was similarly exercised the next day and the sequence continued until the evening of 2 September when Berrima weighed anchor and proceeded in company to Port Moresby.

The submarine force comprising AE1 and AE2 together with the hastily converted merchantman and now submarine depot ship HMAS Upolu and their escort, the elderly small cruiser HMAS Protector, were also due to rendezvous at Palm Island. But these vessels were delayed by engineering defects to Upolu and the slow speed of Protector. As a result, on leaving Townsville on 4 September the support ships were ordered to join the convoy later at Simpson Harbour.

The force now converging on Port Moresby for coal and oil comprised Sydney, Encounter, Berrima, Warrego, Parramatta, Yarra, AE1, AE2, Aorangi and the collier Koolonga and olier Murex. Surely at that time in the largest fleet to have sailed from here, they departed on 07 September, and arrived at Rossel Island two days later where they met the flagship HMAS Australia, together with the colliers Waihora and Whangape. It was here that the final plans were decided for the attack and landings on German New Guinea.

Further reports on Palm Island

An article entitled The RAN and the Capitulation of German New Guinea (NHR March 2014) states: Berrima steamed north into a gale and headed for Moreton Bay to land and collect mail. She then sailed to rendezvous off Lady Elliot Island with the cruiser HMAS Sydney on 22 August 1914. Still not officially aware of their purpose or destination, the men of the ANMEF found themselves at anchor off Palm Island near Townsville the following day. There they underwent two weeks of training to develop skills in the rugged hills, dense jungle and mangrove swamps appropriate to their tasks in German New Guinea.

This is further supported by the story of Able Seaman Herbert Willams RANR who was part of the contingent transported in HMAS Berrima (NHR Dec 2014). Embarked in HMAS Berrima and sailed from Sydney on 19 August 1914 for Moreton Bay where she rendezvoused with HMAS Sydney before proceeding to Palm Island, just north of Townsville. Here the troops received special training in tropical warfare. The naval parties were busily engaged in manning the ship’s boats, transporting troops and equipment each day and gaining experience of coming ashore on both sandy beaches and rocky headlands.

After a busy week of training everyone and their equipment returned to the ship. Noting only seven boats and one motor launch was available to ferry everyone and everything between ship and shore. On 2 September Berrima was joined by the Australian submarines AE1 and AE2 and in company with the cruisers Sydney and Encounter made their way inside the Barrier Reef to Port Moresby where they all coaled and oiled.

Second World War

Allied ships venturing to New Guinea and the South West Pacific regularly sheltered at anchorages inside the Barrier Reef with Cid Harbour in the Whitsundays and Challenger Bay at Palm Island being favoured, the latter having the advantage of being further north. While these anchorages were considered safe from enemy ships and submarines they received a rude awakening in July 1942 when Townsville suffered three bombing raids by Japanese aircraft, luckily with little damage. Whilst these aircraft were at extreme range it demonstrated that Palm Island was not immune from attack. After this event RAAF Catalina aircraft provided daylight air coverage whilst major fleet units were at Challenger Bay. The anchorage was popular as recreational leave to Palm Island beaches was usually granted to ships’ companies.

Perhaps the most illuminating picture of Palm Island is painted by Ian Wrigley when a Sub Lieutenant serving in HMAS Australia in 1943. This is found in a paper, of all things, discussing rugby in the RAN (NHR September 2013). Wrigley says: I took the troop train from Sydney to Townsville (a seven-day journey) and there joined the sloop HMAS Swan for the short passage to Palm Island to join my new ship. At this stage of the war, in June 1943, the cruisers Australia and HMAS Hobart, the destroyers HMA Ships Arunta and Warramunga and US Ships Flusser and Ralph Talbotwere based in the excellent anchorage off Palm Island. It was safe because Japanese submarines did not venture inside the Barrier Reef. From here the cruisers, accompanied by destroyers, rotated on patrols of the Coral Sea.

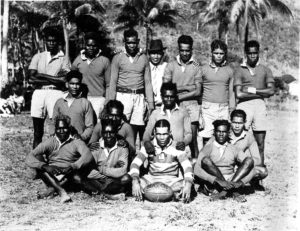

One of my duties in Australia was as the ship’s Physical and Recreational Training Officer and it was my job to find an outlet to improve upon the restrictive shipboard exercise routines. This included deck hockey, boxing and wrestling matches in the starboard waist and small-bore shooting matches on the forecastle. Palm Island had a sports field on which it was possible to have a game of rugby against teams from other ships but, just as importantly, against teams from the local indigenous community who thoroughly enjoyed the friendly competition. It was here that I gained a place in the fiercely competitive Aussie First Fifteen.

The Official War History tells us that in early 1943 in placing ship dispositions to patrol the Coral Sea and support troops being moved forward to New Guinea a number of ships were assigned to Task Force 74 under command of Rear Admiral Victor Crutchley, VC, RN flying his flag in HMAS Australia. Rear Admiral Crutchley was lent to the RAN from June 1942 until June 1944 and saw most of his service in the South West Pacific. Other units were the cruisers HMAS Hobart and USS Phoenix and the destroyers US Ships Selfridge, Henley, Bagley, Mugford, Patterson and Ralph Talbot plus HMAS Arunta. This required a force of at least one cruiser and three destroyers continuously at sea on patrol between northern Australia and southern New Guinea and the remainder at a reef anchorage at short notice for steam. Challenger Bay at Palm Island became the preferred reef anchorage until the end of the year with the two groups alternating in maintaining continuous Coral Sea patrols.

The ships were also assigned other duties and refits were necessary. On the day Finschhafen fell (03 October 1943), Admiral Crutchley’s Task Force 74, then at Palm Island, comprised just one ship, HMAS Australia. The cruiser spent a lonely ten days there carrying out firing practices. On the 13th she was joined by USS Bagley, and on the 15th the two ships arrived at Milne Bay.

Peter Nielsen compiled an interesting list of events in his self-published book North Queensland at War. He relates that the war came to Palm Island on 16 September 1942 when a Volunteer Air Observer Corps (VAOC) observer on the island using his radio sent an immediate plain language message to the Naval Headquarters at Townsville saying that a naval battle was in progress in Challenger Bay. This was later discovered to be cruisers from Task Force 44 carrying out close range weapons firings at sleeve targets, and destroyers carrying out full calibre throw-off firings using another ship as a target.

United States Naval Air Base

One of the wonders of naval aviation is the flying boat, epitomised by the graceful Catalina. A seaplane is a small aircraft that can land on and take off from water, whereas a flying boat is built as a large boat that can fly. It is as well to remember that our first long-range aircraft were flying boats and our first international airport was the flying boat base at Rose Bay. For a while flying boats came to Palm Island.

The most dramatic wartime activities to occur on Palm Island, albeit briefly, was the establishment of a USN Air Base. On 6 July 1943 two officers and 122 enlisted men of C Company of the 55th Naval Construction Battalion (Seabees) left Brisbane to start construction of a Naval Air Station to accommodate squadrons of Catalina flying boats.

The Seabees operated from a temporary tent camp at Wallaby Point where they built a large parking area for up to 12 flying boats with concrete boat ramps and laid moorings for 18 flying boats in Challenger Bay. Construction continued with barracks and offices, galley, mess rooms, water distillation plant and fuel installation. By late September a large number of operational and maintenance personnel began arriving and the naval base became fully operational on 25 October 1943. No local labour and little native material were used during the construction but coral aggregate for concrete was obtained from offshore reefs exposed at low tide.

A war timeline for Queensland shows that in October 1943 United States Navy Air Wing 17 consisting of three PBY-5A Catalina Patrol Squadrons VP11, VP52 and VP101 had established an Operational and Repair Base at Challenger Bay. Supporting documentation indicates that VP52 with an unspecified number of Black Cat (night time) Catalinas and fitted for electronic reconnaissance of enemy targets were based on the island from 16 October 1943 but these were transferred to New Guinea on 22 November 1943.

Next, VP101 with eight Catalinas arrived at the island in early December 1943 but were relocated to Perth, WA at the end of December. VP11, with 13 Catalinas, 46 officers and 99 men arrived on 28 December 1943 but were again relocated to Perth, WA on 24 May 1944.

Also at the southern end of Orpheus Island is the so called Yanks Jetty which was said to be used as a degaussing station for US submarines. While the jetty, or its replacement remains, it is unlikely to have been used for degaussing as a USN degaussing range existed at the entrance to the Brisbane River and USN submarines are not known to have frequented the Palm Islands.

After a brief seven-month operational life the Naval Air Base on Palm Island officially closed in May 1944 and the following month Seabees returned and began dismantling much of the equipment for relocation to forward operational bases. Some of the accommodation remained to be reused by local inhabitants and a few Catalina wrecks still remain on the island. During its operational life the base was largely supported by the supply ship and oiler USS Victoria which transited the east coast between Brisbane and Port Moresby.

The Dark Side

As well as the Palm Islands interlude in early European exploration and utilisation as naval bases during both World Wars there is a dark side to their history which should be addressed.

In small scattered communities the Manbarra people occupied this region prior to European contact. However the contemporary name for the islanders is Bwgcolman, meaning many tribes, referring to the influx over the past century of Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders forcibly removed to Palm Island from elsewhere in Queensland. Today there is a residential community of about 2,700 people from over forty clans or family groups.

The history of the racial tension between indigenous communities and early settlers is complex and outside the scope of this paper. Suffice to say conservative Queensland governments were slow in adopting measures for meaningful integration and self-determination of indigenous peoples.

The Queensland Government adopted an Aboriginal Protection Policy in 1897. Arising from this Palm Island was gazetted as an Aboriginal Reserve in June 1914 but it was not until 1918 when a cyclone destroyed a nearby mainland mission that the first inmates were sent to Palm Island. In another visit in 1916 by the Chief Protector of Aboriginals, he found the island to be ‘the ideal place for a delightful holiday’ and that ‘its remoteness also made it suitable for use as a penitentiary’.

In the first two decades of its establishment as an Aboriginal settlement the population grew from 200 to 1,630 and by the early 1920s Palm Island was the largest Aboriginal settlement in the State. It quickly gained a reputation as a penal colony to which Aboriginals were removed if they were considered ‘disruptive’. Women falling pregnant to white men were removed there, and children were segregated from their parents. The settlement was run by harsh overseers with military like discipline.

The adjacent Fantome Island was gazetted an Aboriginal Reserve in 1925. The following year the Fantome Island Hospital was established and began taking patients suffering from venereal disease. By 1937 Fantome had become a health clearing station where persons were first sent before being admitted to Palm Island. A leprosarium was established on Fantome in 1939. After WWII these medical facilities were gradually closed and only the leprosarium remained when it too closed in 1973.

A Brighter Picture

A brighter picture of a paternalistic Palm Island community is demonstrated in an article found in the Brisbane Telegraphdated 21 May 1938 written by a journalist known as ‘Pilgrim’ provides the following description.

A little to the northward of Townsville and about five hours sail from that city, lie the beautiful Palm Islands. The group is comprised of about 20 islands and rocks lying off Halifax Bay between Magnetic and Hinchinbrook Islands. Great Palm, the largest of the group, is 8.5 miles long and from 1 to 4.5 miles wide, its densely wooded slopes rising abruptly to majestic Mount Bentley. Here on this tropic isle, whose shores are washed with turquoise seas and beaches shaded by the gently swaying plumes of coconut palms, the Government has established an aboriginal settlement.

The launch-master has charge of the waterfront generally, boat-building and repairs. He also makes the bi-weekly run to Townsville in the 40 ft launch Irex. All punts and dinghies or other boats are built under his supervision by native workmen. One is certainly surprised to see that most of their well-built boats are of maple. Many references were made to the excellent workmanship shown by the local tribes when building, thatching, and sewing, saddler and cropping for the authorities showing high regard for their positions.

In a similar time-frame there is a report in the September 1938 edition of the ‘Monthly Record of the Aborigines Inland Mission of Australia’ (AIMA) of a long-desired visit to Palm Island by their Director, Mrs. R. Long. At this time the population of the islands was estimated to be 1,500 or more. This lady made the five hour voyage in Irex before spending a few days in the Mission House on Palm as a guest of the missionaries Mr. and Mrs. Buckley. She was enchanted by the residence built on a sunny hillside about a mile from the church. The view is the most glorious imaginable – with the ocean spreading to the islands a few miles away. The natural beauty has been enhanced by terraced gardens ablaze of bloom. Tropical shrubs and fruit trees and vines, a healthy vegetable garden, bananas and a flourishing pineapple patch, make the surroundings a delight.

Mrs. Retta Long was a Baptist missionary to Aboriginal people, who later in 1905 founded the AIMA, which had rapidly expanded throughout coastal and inland Australia. She noted that until about eight years ago the whole of the population of these islands was under their pastoral care. Since then they had to share the flock with representatives of the Church of England and Roman Catholic religions. This over servicing of spiritual needs caused tensions, with some sects of the Christian Church almost in a turf war, unlikely to benefit their followers.

A visit was made to the school to see the children at work in various classes and they rendered several vocal and musical items very nicely. The workshops below, where the boys were trained in manual work, were most interesting. A day visit was also made to the hospital on Fantome Island but unfortunately with no further details.

During the Director’s visit she notes the arrival of two to three hundred tourists from interstate steamers who were entertained by the dark people with native dances and exhibitions of spear throwing, native fire-lighting and an admirable programme by the school children. Tables of coral, basket-ware and wood-work attracted buyers, and the people made a little money.

While the ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’ is what might be expected for a white Queensland audience, it is to be hoped that the description of an inspection, made over several days by the experienced Director of a large and respected missionary organisation, contains balanced observations.

Recent Developments

A Commonwealth inspired and more enlightened approach to Aboriginal welfare was adopted in the 1960s and by the early 1970s this moved to self-determination with greater emphasis on human rights. An unforeseen consequence of the closure of the mission system was the failure to find a suitable replacement system of management. A malaise caused by high unemployment, alcoholism, violence and welfare dependency found the local community unable to successfully manage its own affairs. This led to further conflict with an entrenched and outmoded administrative and justice system.

In 1986 ownership of the island was transferred to a newly formed Palm Island Community Council, becoming the Palm Island Aboriginal Shire Council in 2004. What should have become a classical tropical paradise, in 1999 received an unwanted epitaph, when Palm Island was named in the Guinness Book of World Records as the most violent place on earth outside a combat zone. The authors based this upon the appalling crime statistics and social measures showing a lack of wellbeing emanating from this small community.

A further low point in relationships was reached in 2004 with a death of an Aboriginal man who had been placed in custody in Palm Island for allegedly causing a public nuisance. His death was treated as murder by the local community resulting in full scale riots and burning of public property. Outside assistance had to be sought to restore order. A subsequent enquiry detailed many recommendations for improvements. While a coronial enquiry found against the local police service, a local mainland jury found the officer responsible not guilty of manslaughter and assault charges.

The Future

While there remains much to do in this troubled community an ambitious ‘Palm Island Planning Scheme’ was produced in 2016. The island is in an exceptional location of natural beauty and is not without resources. Given sound guidance and willingness for improvement benefits should accrue to the overall community. Possibly we might learn from the WWII visit by HMAS Australia and arrange naval ship visits with friendly sporting competitions and offer low key recruitment opportunities.

Perhaps the last word belongs to Ella Archibald-Binge who in the indigenous current affairs program Living Blacksaid: A century ago white settlers transferred a tropical paradise into a prison. A hundred years on, Palm Islands have broken free of their shackles, and are determined to carve a pathway to a brighter future.

Notes:

Our Island Captures – An Account of the Operations of the Australian Expeditionary Force in the South Pacific Ocean 1914, by the late Angus Hermon Wilkinson, published by Hassell & Son, Adelaide, 1919.