- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- History - general, Biographies and personal histories, History - WW1

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Jervis Bay I

- Publication

- June 2019 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

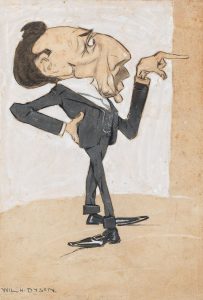

To the returning servicemen Hughes was ‘the Little Digger’ a symbol of Australian self-confidence. Geoffrey Button

Formative years

William Hughes, the father of William Morris Hughes, came from a line of respected tradesmen whilst his mother, Jane Morris, was from yeoman farming stock all from North Wales. The young couple set off from the Principality for the bright lights of London, where William (snr) was employed as a joiner and carpenter at the House of Lords, and to supplement the family income Jane did some domestic work. The Hughes family were pillars of the Welsh Baptist Church at Moorefields in London, where William was a deacon.

Their only child William Morris Hughes was born in London in 1862. William’s mother died when he was aged seven, and accordingly the child returned to Wales to be brought up by his aunt. A bright pupil, he attended Llandudno Grammar School until he turned 14. As a young man he was physically uninspiring; at a height of 5 foot 5 inches he was small, scrawny and suffering from deafness and chronic dyspepsia (gastrointestinal discomfort). He had piercing blue eyes and big ears. What he lacked physically was more than compensated for in mental toughness, intellect and oratorical skills.

His intended career path was that of a schoolmaster and he was apprenticed for five years as a pupil-teacher at St Stephen’s Anglican School, Westminster. Here, under the tutelage of a friendly headmaster, he spent the first hour of every day at lessons before putting in another five hours as a teaching assistant. He also attended evening classes and undertook quarterly assessment examinations. Hughes’s school inspector was the great man of letters and eminent poet, Matthew Arnold. Arnold instilled into the youngster a love of literature, giving him a volume of Shakespeare’s collected works. Despite his small stature a patriotic Hughes also found time to serve as a volunteer with the Royal Fusiliers.

In 1884, aged 22, Hughes took a government assisted passage to the new Colony of Queensland. He was offered a teaching position in the remote outback which he turned down and took to the road undertaking various odd jobs. Eventually finding himself back in Brisbane he then worked his way to Sydney in the galley of a coastal steamer. This led to a series of shore jobs as a kitchen hand before gaining a better paid position with a manufacturer of kitchen equipment.

Billy was living at a boarding house in the inner Sydney suburb of Darlinghurst. Here he met and married his landlady’s daughter, Elizabeth Cutts, who had a young son from a previous relationship. Over the next few years Billy and Elizabeth had three daughters and two surviving sons.

In 1890, using Elizabeth’s family money, they set up shop in Balmain and lived over the premises. Gradually this business developed into an outlet for the sale and exchange of books and a place for political discourse. This was the time of the bitter national maritime strike, into which shearers and coalminers were drawn, in support of maritime workers.

Hughes edited a radical weekly called New Order, giving him a platform to enter state politics, and in 1894 he won the working-class waterfront seat of Pyrmont and Ultimo. His energetic organisational skills gained him various union posts including secretary of the Wharf Labourers’ Union. Using his union power base Hughes easily won a seat in the new Federal Parliament. He supported Australia having its own defence force and advocating conscription of all males between the ages of 18 and 60 to undergo part-time military training. He joined the National Defence League to influence public opinion in favour of a national defence policy.

Working in arbitration on behalf of the unions allowed Hughes to qualify for the Bar, and in 1904 his first major political role was his appointment as Minister for External Affairs and Chairman of a Royal Commission on the Navigation Bill. Hughes carefully examined all aspects of the Australian maritime environment and gained considerable expertise in this field. After two years the Royal Commission produced a report exposing the harsh conditions under which merchant seamen worked and recommended reforms. Meanwhile the British Government became interested and proposed Britain and New Zealand join with Australia to secure unified action. When this took place Hughes became one of the delegates, resulting in his first return to his homeland where his work ethic created a favourable impression.

On the domestic front, in 1906 Elizabeth Hughes died, leaving a considerable void. In 1907 leadership of the Labor Party passed to Andrew Fisher with Hughes as his deputy and the following year Hughes became Attorney-General. Between 1907 and 1911 the conservative Daily Telegraph invited Hughes to provide a weekly column presenting ‘The Case for Labor’ in which he promoted moderate socialism. In 1911 he remarried, this time at a different social level, to Mary Campbell, a pastoralist’s daughter. By now he had a fine home, a motor car and a hobby farm on the Hawkesbury River.

The Australian federal parliamentary system was still evolving, and from Federation to the outbreak of the Great War there had been five elections, with a sixth due on 5 September 1914. During this time there had been a total of nine Prime Ministers. With war clouds looming in September 1913 a general election was called, resulting in a return of the Liberals by a majority of one with Joseph Cook becoming Prime Minister. The instability of Cook’s government brought about another election and during the campaign the British Empire found itself at war with Germany. Labor won office with Hughes serving as Attorney-General under Prime Minister Fisher. On 3 August 1914, Cabinet agreed to offer to place the newly acquired Australian fleet under control of the British Admiralty, and to send an expeditionary force of 20,000 troops overseas whenever it was required by the Imperial Government.

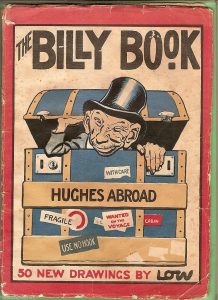

In October 1915 Fisher resigned to become High Commissioner in London and Hughes, unopposed, became Prime Minister. He felt secure enough to visit England in early 1916 as he wanted a more effective voice in the progress of the Great War. In particular Hughes was concerned that Australia’s exports were hampered by insufficient shipping and for the need to gain control of the ex-German Pacific colonies.

Hughes, accompanied by his wife Mary, a qualified nurse, and their infant daughter Helen, sailed unheralded from Sydney on 26 January 1916 with calls at New Zealand and Canada, then travelling overland to the US. They landed in Vancouver on 19 May 1916 and crossed the border to Seattle where ten wooden ships were being built for the Australian Government. Progress was good as three had already been launched and a fourth would be the next day. They also arranged to see some concrete ships and enlist the help of an expert on these to visit Australia with a view to constructing them under licence.

The party proceeded to Washington to meet President Woodrow Wilson, then sailed from New York in the Red Star liner Finland, reaching Liverpool on 7 March. The Australian Prime Minister’s energetic approach won him many admirers in Britain and although not impacted by the complexities of European policymaking, he gained a reputation as a statesman and was to strike up a rapport with another fiery Welshman, Lloyd George. The opportunity was taken to visit Australian troops on the front line in France before returning home via troopship on 31July 1916. The new-found status of our Prime Minister is aptly summarized in the following newspaper description:

Before Mr. Hughes went to England he was plain ‘Billy’: in the cables he was Mr. Hughes…now that he has received the ‘freedom’ of the cities of London, Cardiff, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Bristol, Liverpool, Manchester, York, Sheffield and Birmingham, and doctorates from the Universities of Edinburgh, Glasgow, Birmingham, Oxford and Wales, and is a Privy Counsellor in addition, what is one to call him? Seems sacrilege to say ‘Billy’ nowadays. (Tweed (NSW) daily newspaper 29 July 1916.)

Upon returning home he was involved in the hostile conscription debate. Hughes preferred to legislate for conscription as was being done in Britain, Canada and New Zealand but he feared losing a closely contested vote, especially as many Irish-Australians were against continuation of the war. As an alternative a referendum was held on 28 November 1916 where ‘No’ triumphed by a narrow margin.

A wartime double dissolution election was called in May 1917 with Hughes changing horses from Labor to Nationalist but again winning a mandate. As manpower shortages at the front continued, a second referendum was called in November 1917, which was defeated by a wider margin than the first.

The Imperial War Cabinet met in London in June 19181to which the Dominion Prime Ministers were invited. To satisfy this requirement a more ambitious visit was made in RMS Niagara, which sailed from Sydney on 26 April 1918.Hughes was again accompanied by his wife and daughter. Included in the party were Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for the Navy Joseph Cook and Mrs. Mary Cook, the Solicitor-General Sir Robert Garran and John Latham2, a naval reservist and brilliant lawyer with expertise in Pacific affairs and naval intelligence. Latham acted as Cook’s secretary. The extensive party included Percy Deane, Hughes’s personal assistant, and his physician, Dr. R Mungovan, two stenographers and a messenger. While he was not part of the official entourage, from the time they reached England, journalist Keith Murdoch was never far distant. In London they lived in a house provided by the British Government.

When they reached Auckland they were joined by the New Zealand Prime Minister William Massey and his Minister for Finance Joseph Ward, who then traveled with them to Canada. On reaching Vancouver they traveled by train to Ottawa to meet with the Canadian Prime Minister Robert Borden and thence to Washington for discussions with the American President Woodrow Wilson. Hughes and Cook arrived in New York on 13 May and were in Washington from 27 to 30 May. They were received by President Wilson on 29 May, however the meeting lasted only thirty minutes with the academically devout President being unimpressed by the forthright views of his guest.

Imperial War Cabinet

In North America the parties made separate transport arrangements to England, with the Canadian and New Zealand delegates arriving in London on 8 June. At the first meeting of the Imperial War Cabinet on 12 June the Australian delegation was limited to the Solicitor-General Robert Garran and LCDR John Latham. It was not until the meeting of 17 June and afterwards that Prime Minister Hughes and Minister for the Navy Cook attended.

Possibly to prevent Prime Minister Hughes from grandstanding, a Royal Navy cruiser HMS Leviathanwas placed at his disposal to transport him from New York to England, but the rules against females travelling aboard RN ships were unbending. Mother and daughter and the remainder of the official party departed from New York in the troop transport ex-RMS Adriaticon 05 June 1918. They were now part of an escorted convoy of eight ships carrying American troops and equipment to the war in Europe. After berthing at Liverpool the official party was reunited at Euston Station in London on 15 June.

Following the Imperial War Cabinet meeting other PMs departed, but Hughes remained to argue the case for better access for Australian products to English markets. He again visited Australian troops in France. With the approach of peace, it was agreed that Hughes and his entourage should remain to safeguard Australia’s interests. This gave Hughes his moment on the international stage where he won a mandate over New Guinea and over the phosphate rich island of Nauru. To Australian returning servicemen he was ‘the Little Digger’, a symbol of Australian self-confidence. He returned home with many of them in a troopship.

Learning the Ropes in Wooden Ships

The work of Hughes on the Royal Commission into the operation of the Navigation Bill, his association with maritime unions and a penchant for nationalism drove him to support a union push for a local merchant fleet manned by Australians. This also fitted with a ‘White Australia’ policy as many British merchant ships which operated on the Australian waterfront were majority crewed with low-cost Asian labour.

Upon the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, by astute management of its military and naval forces Australia was fortuitously able to impound 27 German and one Austrian vessel through Prize Law. A merchant fleet of well found vessels had been obtained at virtually no cost. Initially the Transport Branch of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) operated these ships. Some were used as troop transports and supply ships and others fulfilled commercial purposes.

In 1916 the Commonwealth Government Line of Steamers (CGLS) came into being through Prime Minister Hughes invoking the War Precautions Act to requisition money for a payment of £2,047,000 for 15 British tramp ships. With war-time conditions shipping was at a premium and this was a high price for these vessels. Each ship’s name began with ‘Austral’ such as Australfield– collectively they were known as ‘the Australs’. In 1918 management of the Australs and the requisitioned enemy ships were all placed under the CGLS.

Because of wartime losses hulls remained at a premium, affecting Australia’s ability to ship produce. As steel was in short supply and the local steel manufacturing industry was in its infancy, an American proposal was received to revert to building ships of wood, which was in plentiful supply. This resulted in the Commonwealth in 1917 entering into contract with the Patterson-MacDonald shipyard of Seattle for the supply of 10 wooden steam driven cargo ships. The contract was later amended for five steam powered and five motor ships.

In January 1918 the Sydney firm of Kay McNicol was co-opted by Prime Minister Hughes to present plans for the construction of similar wooden merchant ships. Initially this was to be for 24 ships divided amongst four builders for six ships each, with three builders in Sydney and one in Western Australia. With the end of the Great War the need for these vessels was reassessed and only the first two ships, which were already under construction by Kidman & Mayoh at a slipway at Kissing Point on the Parramatta River, were completed. It is noteworthy that Kidman & Mayoh had never before built ships.

The whole history of the wooden ships was a disaster. As ocean going vessels of about 3,000 gross tons with a maximum speed of nine knots they were too small and too slow to be commercially viable. Many were poorly built with extensive repair work required to make them seaworthy. Litigation with the American builders, who became bankrupt, lasted many years. As soon as possible these vessels were sold at bargain basement prices. The Commonwealth incurred losses of £2.34m on this venture. In addition, losses on the two Australian built ships were estimated to be about £300,000.

The fate of the two locally built ships Burnside and Braeside, which were considered unseaworthy, was pitiful. Burnside was burnt out on the stocks on 4 September 1923 and Braeside was towed outside the Heads on 21 December 1923 and set on fire.

The next venture into shipbuilding was however successful with the construction in Australia of two Dale-class, and in Britain, of five Bay-class ships3.

The 10,000 gross ton Dales were twin screw refrigerated cargo ships built at Cockatoo Island Dockyard and at the time the largest such vessel built in country. The Bays were handsome twin screw cargo-passenger vessels of 12,800 tons. Given the past mistakes these ships were a great accomplishment and they were much admired.

Esperance Bay, Hobsons Bay, Moreton Bay and Jervis Bay became armed merchant cruisers and Largs Bay a troopship. Under the command of Captain Fogarty Fegen, RN, VC, Jervis Bay is well known for her heroic action against the German pocket-battleship Admiral Scheer where against overwhelming odds she was responsible for saving the majority of her convoy of 38 ships.

By 1923 half of the Government owned fleet of fifty-four ships was laid up and during the following three years most of the ships were disposed of at bargain prices. However, with the Dales and Bays the nationalised shipping company (CGLS) retained the nucleus of a fine merchant marine. These ships were as good as any others afloat and their standard of accommodation for both passengers and crew was excellent. Crew accommodation, pay and entitlements were possibly the highest in the world. But this was not good enough for a rapacious union movement which called for more and through a series of petty strikes virtually brought the company to a standstill. Surely William Morris Hughes, a visionary, a man of the people, had the ability to control the unruly maritime unions.

But Hughes’s influence had waned, with no end in sight the Government decided to sell its shipping interests to a British monopoly and by 1928 it no longer had any ships on the Australian register. The Australian merchant fleet would never fully recover from this blow.

Relationships with the Australian Navy

While Hughes was generally supportive of the Australian navy he could afford to leave much of its administration to his close friend and colleague Senator George Pearce who first became Minister for Defence in 1908 and continued in that role during the whole of the Great War and beyond. This confidence was well placed as Pearce was most competent and a great advocate of the RAN.

In May 1918 the Admiralty produced a memorandum for consideration of the Imperial War Conference that proposed a single navy for the Empire. This stirred up national resentment with Hughes but he left the running of this important issue with his Navy Minister Cook, which most likely fell to the latter’s assistant John Latham. The result was that all Dominions rejected the proposal. As a compromise it was agreed that Admiral Jellicoe should tour the Dominions to advise on the needs of Dominion navies.

Hughes crossed swords with the naval establishment when HMAS Australia returned home in June 1919 with an incident in Fremantle where stokers refused to take the ship to sea, resulting in the court-martial of five ringleaders. In a nation recovering from a horrendous war, naval discipline by way of prison sentences meted out to the culprits seemed out of touch with community expectations and political pressure was brought to bear for reduced sentences. The Fleet Commander, the Australian born and popular Commodore John Saumarez Dumaresq, and the First Naval Member of the Naval Board, Rear Admiral Grant, threatened to resign in what they considered political interference in naval justice. Luckily they were persuaded to withdraw their resignations and the incident was largely forgotten.

In April 1922 John Dumaresq, now a Rear Admiral, had resigned and was returning home to England. Prior to his departure the Admiral took the opportunity to speak his mind to reporters. He expressed fears held throughout the Australian Fleet chastising the Government for the lack of appropriate funding for the navy, and expressing the hope that the Australian Navy would never fall below three light cruisers and an adequate number of other ships such as submarines. ‘If she falls below three light cruisers, the soul of the Australian Navy will have expired, as the spirit, morale – call it what you will – of a navy cannot be maintained with anything less than three light cruisers’.

These comments incensed Prime Minister Hughes who responded by saying the Admiral’s comments were ‘unfortunate and showed rather bad taste’ and continued, ‘it is the business of the Naval Board, of which Admiral Everett is chief, to advise the Government upon naval policy, and it is the business of the admiral in charge of the fleet to command the forces placed at his disposal by the Government on the advice of the Naval Board. Therefore, whatever is to be said in reference to the naval policy of the Government should be left to the responsible naval adviser’. This rebuke was hotly resented by naval officers who supported the comments of the late fleet commander. The last word came from Admiral Dumaresq who said ‘it would not become me to reply to such a great man as the Prime Minister of Australia’, adding that his intent was to be open with the Australian people about his beliefs. Tragically Admiral Dumaresq, who suffered from ill health, was never to return home as within a month he died at an American hospital in Manila and he was buried there with full military honours provided by American armed forces.

Dumaresq’s comments related to Government restrictions being placed upon the RAN because of economic stringencies. With the onset of the Great Depression the RAN suffered severely. Recruiting ceased and no new entries were accepted into the Naval College which had been moved from Jervis Bay to the Flinders Naval Depot. Manpower was reduced and the number of ships in commission fell, at its lowest level to just four ships: two cruisers, a seaplane tender and one destroyer. But by the mid-1930s there was a progressive movement towards rearmament and the RAN quickly returned to a formidable naval force.

Other Achievements

William Hughes was also instrumental in providing support to the establishment of the Returned Services League (RSL) and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). He also set up the Commonwealth Oil Refineries which had the effect of halving the local price of motor fuel, and encouragement was given to the search for oil deposits in Australia. He endeavoured, with limited success, to provide a regular service of airships between Britain and Australia. He also secured approval to establish a direct overseas wireless link from Australia to other major centers. As a consequence, Hughes became a director of Amalgamated Wireless Australia (AWA).

By 1923 the Hughes magic was fading and with lack of support he resigned as Prime Minister on 2 February 1923, retiring to the back bench. Hughes made another tilt for power when as part of a coalition government in October 1934 he became Minister for Health and Repatriation but only lasted a short while, resigning the following November. However, within three months he was back as Minister for External Affairs until April 1939, then as Attorney-General, and from September 1940 as Minister for the Navy. While the approach of the Second World War stimulated the old warhorse he was now becoming a spectator as younger men sought power.

On his 90th birthday his parliamentary colleagues gave him a testimonial dinner. A week later on 28 October 1952 he died of pneumonia.

Summary

William Morris Hughes was Prime Minister of Australia from 27 October 1915 to 9 February 1923, a then-record period of 7 years, 3 months and 14 days, and he led a politically diverse country through the majority of the Great War and beyond.

The international image Australia sought to portray at the time of the Great War was of a breed of tall, carefree, country boys who became bronzed warriors. In this respect their political leader, the symbolic ‘Little Digger’, was the very opposite. Hughes was portrayed as a poor self-educated working class migrant, nurtured by the union movement to represent the aspirations of the working class. Hughes in fact came from a solid lower-middle class background, was well educated and continued with his studies as is evidenced by admittance as a barrister-at-law, and acknowledged with the accolade of being made a Privy Counsellor, and the award of honorary doctorates from prestigious universities. The real Hughes was more at home with the ideals of Plato and Kant rather than the radical socialism of Marx and Lenin.

Hughes was an enigma, a man of contradictions; starting with a socialist manifesto he became comfortable in the society of newspaper barons, landowners and industrialists. During his amazing career he achieved much but in naval and maritime circles he will be remembered as doing more than any other in building a fleet and then losing a fleet.

Of the immediate Hughes family, tragically their 21-year-old unmarried daughter Helen died in London in 1937 after complications following childbirth. William Hughes died in Sydney on 28 October 1952; his wife Mary died on 2 April 1958 and is buried in the Sydney Northern Suburbs Cemetery next to her husband and daughter.

References

Bridge, Carl, Makers of the Modern World – The peace conferences of 1919 – 23 and theiraftermath, London: Haus Publishing Ltd, 2011.

Gratton, Michelle, Ed, Australian Prime Ministers – Revised & Updated, Sydney: New Holland Publishers, 2016.

Imperial War Cabinet Minutes 10 January 1918 – 03 July 1918, filestore.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pdfs/large/cab-24-151.pdf.

Imperial War Cabinet Minutes 13 August 1918 – 30 December 1918, filestore.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pdfs/large/cab-23-42.pdf.

Horne, Donald, In Search of Billy Hughes, Melbourne: MacMillan, 1979.

Levi, Werner, American-Australian Relations, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, 1947.

McDonnell, Captain R., Build a Fleet, Lose a Fleet, Melbourne: The Hawthorne Press, 1976.

Sheden, Douglas, From Boundary Rider to Prime Minister, London: Hutchinson, 1916.

Spartalis, Peter,The Diplomatic Battles of Billy Hughes, Sydney: Hale & Iremonger, 1983.

Notes

- From the time of end of the Boer War to the start of the Second World War there were a number of Committees on Imperial Defence to which colonial, later Dominion, representatives were invited. In 1917 Lloyd George instituted an Imperial War Cabinet with executive powers. It first met and held a number of meetings between March and May 1917. Owing to a federal general election in May 1917 Australia was not represented during this important series of meetings.

- LCDR John Greig Latham RANVR was seconded to the official delegation for the 1918 Imperial War Cabinet meetings. Although recognising the achievements of Hughes he was critical of the Prime Minister’s excesses and affronted by his manner in dealing with diplomatic issues. In 1923 Latham was amongst an influential group who sought the resignation of Prime Minister Hughes. Sir John Latham later became Chief Justice of the High Court. Between the wars Latham was one of the few men in Australian politics with naval experience.

- All five Bay-class ships were sold but there were some later and confusing name changes,Esperance Baybecoming Arawaand then Hobsons Bayrenamed Esperance Bay, both these vessels and their sister Moreton Baywere later converted in Australian shipyards to Armed Merchant Cruisers (AMC). Jervis Bay’s conversion to an AMC was carried out at St John, New Brunswick, Canad