- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- None noted

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- June 2021 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

The spread of Coronavirus and its worldwide impacts have brought home the need for quarantine as a means of segregating those with suspected infection from the general population. This paper sets out to examine the history of quarantine and the suitability of current day practices.

Plague and Pestilence

A brief historical study tells us plague and pestilence were known to the Egyptians from about 1900 BC. While the Book of Exodus might be of dubious accuracy it is based on a series of natural disasters that occurred during these times.

The most significant plagues have been grouped into three pandemics known as the First Pandemic (Justinian Plague), Second Pandemic (Black Death) and Third Pandemic (Spanish Influenza). Each caused devastating mortality across continents resulting in changes to the social and economic fabric of society. Hence the reluctance of the World Health Organisation to term the present COVID-19 outbreak a further pandemic.

Reliable chronicles tell of the Antonine Plague AD 166, brought to Rome by victorious armies returning from central Asia, followed by the Cyprian Plague which struck in AD 249, and the Justinian Plague, afflicting the Byzantine Empire in AD 541 which started in central Africa, came to Egypt and was carried by ships throughout the Mediterranean.

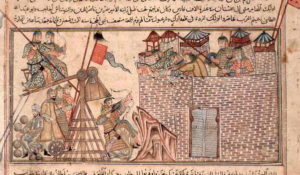

In the middle ages the Mongols who controlled Crimea allowed traders from the Republic of Genoa to establish a settlement at Kaffa (now Feodosiya). This became a flourishing seaport housing one of the world’s largest slave markets. Because of religious differences between Muslim hosts and Christian guests there was simmering discontent which in 1343 broke out into an attack on the settlement. The Mongols under Jani Beg, Khan of the Golden Horde, were repulsed by the defenders who were able to maintain supplies from the sea. This led the Mongols to lay siege to the settlement.

Biological Warfare

The Black Death which had raged in central Asia since about 1330 travelled along the Silk Road, reaching Crimea during the siege. The plague spread through the ranks of the Mongol army and many were struck down. During this time of torment, the attackers hurled infected corpses over the city walls in the first recorded use of biological warfare with defenders watching in horror as putrid bodies fell from the skies. Bodies were thrown into the sea so the Black Death infected Kaffa.

When the siege ended many fled, sailing for their homelands. Unfortunately, they took with them the plague which had accounted for the deaths of about half the population of Central Asia and inflicted a similar disaster upon their European brethren.

The Black Death enters Europe

When a fleet of 12 ships docked in the Sicilian port of Messina in 1347 locals were horrified to find most of the sailors and passengers dead and those who were alive gravely ill and covered in sores oozing pus. The disease they carried was initially spread by rats infested with fleas which transmitted the disease to humans. Sicilian authorities ordered the death ships back to sea but it was already too late, with disease spreading quickly through the powerful city-states of Florence, Genoa and Venice. The pestilence then moved into central Europe and over the next five years killed over one third of the population.

Medicine was impotent against plague and the only way to escape infection was to avoid contact with infectious persons and contaminated objects. Thus, city-states prevented strangers from entering, particularly merchants and minority groups such as Jews. A sanitary cordon was imposed by armed guards along transit routes and at access points. A rigid separation between healthy and infected persons was accomplished through the use of makeshift camps.

Third Pandemic Plague

The Third Pandemic started in Yunnan in 1855 and spread slowly throughout China reaching Hong Kong in 1894, and was then taken by ships throughout the world, reaching India in 1896 where it was responsible for more than 20 million deaths. London was infected in 1900 and Sydney in the same year. This bubonic plague waxed and waned over many years and was not finally extinguished until about 1950.

The small but worrying bubonic plague which occurred in Australia between 1900 and 1925 was spread from waterfront shipping activities where infected rats passed on the disease through fleas to humans. The worse affected areas were poorer unsanitary inner-city housing. Initial outbreaks can be traced to Sydney in the summer of 1900 and over the entire period there were 1 371 recorded cases leading to 535 deaths.

Quarantine

Quarantine was first introduced in 1377 at Dubrovnik on the Dalmatian coast. Thence a permanent plague hospital, a lazaretto (after the biblical Lazarus), opened in the Republic of Venice in 1423. At this time the Italian states were world leaders in standards of public health and hygiene.

The procedure adopted in Venice was for lookouts to be posted on the prominent church tower of San Marco in order to identify suspect ships which were required to anchor, with the captain taken off by boat to the health magistrate’s office. Here he was kept in an enclosure where he spoke at a safe distance through a window. The captain had to show proof of the health of his crew and passengers and provide information on the origin of merchandise carried. If there was a suspicion of disease, his ship was taken to the quarantine station where crew and passengers were isolated and the vessel and its cargo thoroughly fumigated. This practice, called quarantine, was derived from the Italian ‘quaranta giorni’ meaning 40 days.

Other similar facilities were established at major trading ports throughout the Mediterranean. Lazarettos consisted of buildings used to isolate passengers and crews of ships suspected of having plague and merchandise was unloaded into designated buildings. Procedures for sanitation of various products were prescribed with wool, yarn, cloth, leather, wigs and blankets considered those most likely to transmit disease. Treatment consisted of continuous ventilation and some were immersed in running water for 48 hours.

The first British quarantine regulations were not drawn up until two centuries later in 1663 and afterwards similar systems were adopted by most maritime nations.

Quarantine in Australia

After the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788, those who arrived on later ships were subject to medical examination, and were under medical care during the voyage. They were mainly carried in transports under government contract and within the constraints of those times were generally well managed. However, after 1830 there was an increase in the number of free settlers seeking passage in commercial ships with insufficient medical checks, overcrowding, poor diets and inadequate ventilation, all leading to the easy spread of contagious diseases such as cholera and smallpox.

The New South Wales Quarantine Act of 1832 influenced the establishment of permanent facilities for the detention of vessels, passengers and crews at North Head near the entrance to Sydney Harbour. During the operation of this station from 14 August 1832 to its closure on 29 February 1984 some 580 vessels were quarantined, involving 13,000 persons of whom 572 died and were buried there. In due course other Australian colonies built similar but smaller quarantine stations.

Following federation, Customs and Quarantine Controls came under commonwealth jurisdiction in 1908. They are now designed to prevent the introduction, establishment or spread of human, animal or plant pests and diseases in Australia. Over time the process has become more complex involving many levels of government agencies which now include Border Protection and involves off-shore detention facilities.

Spanish Influenza comes to Australia

On learning of the outbreak of influenza (Spanish Flu) in New Zealand in October 1918, Australia implemented maritime quarantine procedures with 323 ships being inspected. From these 1,102 persons were found to be infected and hospitalised. Another factor affecting the outbreak of influenza was the return from Europe to Australia of troopships with their thousands of soldiers, some with newly acquired families.

There are many similarities between the outbreak of disease in 1918 and that occurring more than a century later. The situation then was generally well controlled in Australia but still cost 15,000 lives. In neighbouring New Zealand, the situation was not well handled and with a much smaller population 9,000 lives were lost. This might have some bearing upon the zealous measures implemented by current New Zealand authorities.

There is an excellent complementary article The Navy and the 1918-19 Influenza Pandemic by Greg Swinden in this magazine, with further discussion to be found in that paper.

The present day and Coronavirus

The world must wake up and consider this enemy virus as public enemy No 1, World Health Organisation chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus told reporters on Tuesday 11 February 2020, adding that the first vaccine may be 18 months away.

The present cause célèbre ‘Coronavirus’ is a form of influenza, some properties of which remain a mystery to scientific and medical fraternities, with no antidote currently available. Coronaviruses are zoonotic diseases, meaning they can spread from animals to people. In 2002-2003 a similar coronavirus epidemic known as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) spread across 30 countries infecting 8,437 people, with an extremely high mortality rate resulting in 813 deaths.

The present Wuhan coronavirus, now known as COVID-19, shares about 80% of its genetic code with SARS. Coronavirus was officially named COVID-19 by the World Health Organisation (WHO) where ‘CO’ stands for corona, ’VI’ for virus and ‘D’ for disease and 19 for 2019, the first appearance.

Bats were the original hosts of SARS with the disease unwittingly transmitted to other species through contact with their excrement or saliva. The SARS virus is thought to have jumped from bats to weasel-like animals known as palm civets and thence to humans. This happened in wet markets in Guangdong province north of Hong Kong.

Wuhan, a city of 11 million people in the central province of Hubei, lies about 700 km west of Shanghai. The disease is believed to have originated in a wet market where fresh meat and live animals were sold. The Wuhan Health Commission confirmed the presence of a new virus with the first patient exhibiting symptoms occurring on 8 December 2019, but they did not reveal the outbreak publicly until 31 December, with authorities downplaying the threat. The first associated death of a male who worked at the Wuhan wet market occurred on 9 January 2020.

In preparation for Lunar New Year festivities (25 January to 8 February 2020) many Chinese, unaware of the contagious virus, travelled across the country and abroad to spend time with their families. During this period five million residents left Wuhan resulting in widespread transmission of the disease throughout China and adjacent countries.

It was not until 23 January 2020 that Wuhan was placed in quarantine, halting all public transport. The order prevented any buses or trains from coming into or leaving the city and grounded all flights. Further travel restrictions were later placed on adjacent cities with about 50 million people affected by the lockdown.

On 24 March 2020 at the launch of a report on the socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19 the United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres warned that the world faces the most challenging crises since World War II, confirming a pandemic threatening people in every country ‘that will bring recession that probably has no parallel in the recent past.’

The latest news (early May 2020) hopefully tells us that the pandemic is nearing its peak and may quickly wane. The disease has now spread worldwide with more than 3.3 million persons infected of which about 240,000 have died, and importantly over 1.0m have recovered. Disturbingly, the overall death rate has reached more than 7%. While countries close to the original Chinese epicentre appear to have contained the disease it remains rampant in Europe and currently the United States, which has the unenviable position of being first in the league table with more than 1 million confirmed cases. Very few cases have been reported from highly populated regions such as Indonesia and India and there remains considerable potential for the disease spreading in areas with less robust health services.

The Cruise Ship Industry

The United States Department of Health and Human Services Centre for Disease Control and Prevention in its “2020 Yellow Book” provides guidance on risk of transmission of disease on cruise ships, saying:

Cruise ship travel presents unique combination of health concerns. Travellers from diverse regions brought together in often crowded, semi-enclosed environments on board ships can facilitate the spread of person-to-person, foodborne, or waterborne diseases. Outbreaks on ships can be sustained for multiple voyages by transmission among crew members who remain on board, or by persistent environmental contamination.

Over recent years the cruise ship industry has expanded enormously becoming the fastest growing category in the leisure travel market with the forecast annual number of global passengers in the order of 30 million. With this growth ships have become ever larger with the latest Symphony of the Seas of 228,000-tons carrying about 6,000 passengers and over 2,000 crew. While the maritime city of Sydney struggles to provide sufficient berths for cruise ships a proposed new cruise terminal at Botany Bay, to be jointly funded by the State Government and the cruise industry, now appears doubtful.

The cruise industry is dominated by the American owned Carnival Corporation and the German and Spanish owned Royal Caribbean with 70% of the world market, with the American and Chinese owned Norwegian Cruise Line with 10% coming third. As the industry operates on slim margins most ships sail under flags of convenience which provide tax and labour law advantages to owners, but the countries in which they are nominally registered have virtually no means of physically supporting the industry.

Unfortunately, the next epicentre of the disease outside mainland China was the cruise ship Diamond Princess,quarantined in the Japanese port of Yokohama. Another significant centre of the disease was later found in April on her stablemate Ruby Princess, berthed in Sydney.

On her voyage to Japan the Bermudian flagged Carnival Cruise 116,000-ton ship Diamond Princess carried 2,666 passengers and 1,045 crew. Nearly half the passengers were Japanese, but a high proportion of the remainder were from North America and Australia – 388 Americans, 352 Canadians and 226 Australians.

On a previous short voyage, a passenger from Hong Kong embarked in Yokohama on 20 January 2020 and disembarked in his hometown on 25 January. He subsequently visited a hospital in Hong Kong and on 01 February was diagnosed with coronavirus disease. As a result, when the ship next visited Yokohama she was detained by Japanese health authorities and placed in quarantine with confirmed cases taken ashore for medical treatment.

While in quarantine passengers were confined to their cabins with meals being delivered. Passengers in interior cabins without windows were allowed to step onto the outer deck for a few minutes each day while wearing respiratory masks. Crew members were particularly at risk since they shared cabins with common mess rooms. During the quarantine, the numbers of confirmed cases of coronavirus aboard Diamond Princess grew to an alarming number of 712 cases (including 11 deaths) amongst passengers and crew, representing nearly 20% of the ship’s complement.

After a 14-day period on board passengers who had been tested and were deemed clear of the virus were allowed to leave the ship with North American and Australian government authorities making arrangements to fly their citizens home. On 20 February a special Qantas flight brought 180 Australian passengers to Darwin where they were subject to a further 14-days quarantine at the Howard Springs quarantine facility. After arrival at the Howard Springs facility nine ex-Diamond Princess passengers proved to have coronavirus and were flown directly to isolation facilities in their home states. In early April all passengers and crew had been landed and most returned to their homelands with the ship remaining in Yokohama undergoing an intensive disinfection program.

On 5 March 2020 another ship Grand Princess, in almost identical circumstances was detained off the American coast whilst on passage to San Francisco. On the previous voyage between San Francisco and Mexico a passenger became ill and died of coronavirus. The crew and 62 fellow passengers from that voyage remained on board and the disease spread with investigations confirming 103 persons (passengers and crew) contracted the disease. The ship and its crew were placed in quarantine and anchored in San Francisco Bay with passengers disembarked and quarantined ashore.

The experience from both Diamond Princess and Grand Princess supports the argument that crowded cruise ships act as an incubator for the spread of viral disease. It also proves that those who test negative to a contagious virus should be removed from ships to undertake their quarantine in specialised facilities.

As of 1 April 2020 there were 22 cruise ships, irreverently termed ‘Bug Boats’, in Australian waters, ranging in size from the mammoth 168,000-ton Ovation of the Seas to the boutique 1,800-ton Coral Discoverer. While most had discharged their passengers, some had not, and they had over 16,000 crew members on board. The difficulty here is logistics as the crews predominately come from India, the Philippines and Indonesia. Cruise ship operators had to repatriate as many crew members as possible and prepare small steaming parties taking them to safe havens with skeleton crews maintaining the vessels while they remain out of service.

Having 22 cruise ships with 16,000 crew and 40,000 passengers off the Australian coast at one time is unprecedented. Australian authorities appeared unprepared, overwhelmed and unable to cope with this sudden influx.

The Armed Forces

On 25 February 2020 the United States Armed Forces in Korea announced the first service-related case of coronavirus with a young soldier from its 28,500 personnel in country testing positive to the disease. As a precaution personnel belonging to the USN 7th Fleet based in Japan were required to undergo checks for coronavirus. A number of cases appeared in the ADF with early reports stating 33 personnel had tested positive and were placed in quarantine.

The large 1,000 bed USN hospital ships Comfort and Mercy which have been committed to supporting civilian medical infrastructure have themselves been handicapped with a small number of crew members succumbing to coronavirus. On 25 April the USN confirmed the Arleigh Burke-class guided missile destroyer USS Kidd, serving in the Caribbean, had 64 cases of COVID-19 amongst her 350 crew.

Other navies to be involved include the French nuclear aircraft carrier and flagship Charles de Galle which together with the destroyer Chevalier Paul returned to Toulon from exercises in the Baltic, two weeks early, owing to an outbreak of coronavirus where nearly 1,100 sailors tested positive to the disease.

Meanwhile MS Dolfijn, a Dutch submarine on a North Sea mission, returned early to the Den Helder base because 15 of her 58 crew reported sick with flu-like symptoms, with eight testing positive to COVID-19.

Members of the ADF have been assisting State Police in monitoring overseas arrivals and hotels where persons under quarantine are being detained during their period of isolation to ensure quarantine conditions are maintained. The RAAF has also flown Defence medical personnel to assist in northern Tasmania where heath facilities have temporary closed because of an outbreak of COVID-19 amongst hospital staff. Approximately 1,630 ADF personnel are involved.

Virus brings down Navy Captain and Navy Secretary

On 1 April media reports said Captain Brett Crozier, commanding officer the of the USN nuclear carrier Theodore Roosevelt alongside in Guam, sought permission to isolate the bulk of his crew of over 4,000 on shore as over 150 tested positive to COVID-19. This disease later caused 940 cases (including Captain Crozier) plus one death.

Captain Crozier’s communication was leaked and published in The San Francisco Chronicle leading to the Acting Secretary of the US Navy, Thomas Modly, to announce that Captain Crozier had been relieved of his command for showing ‘extremely poor judgement’ in widely disseminating news about coronavirus spreading quickly throughout his ship.

On Monday 6 April Acting Navy Secretary Modly flew to Guam where he berated the crew saying ‘If he didn’t think that information was going to get out into the public…then he was too naïve or too stupid to be the commanding officer of a ship like this…the alternative is he did it on purpose’. Amid rebukes from members of Congress Mr Modly later issued an apology for his words and on 8 April Defense Secretary Mark Esper said Mr Modly had resigned.

The Australian Response

As the threat intensified, on 26 February the Australian Government announced it had activated its emergency response plan to an impending coronavirus pandemic. In March the Government announced extraordinary measures, not seen before in peacetime, placing the nation in a series of lockdowns severely restricting the movement of persons, goods and services. Flights were drastically curtailed but passengers were allowed entry with minimal effective health checks. Also not handled well was the lack of restrictions placed on passenger ships entering our waters.

As the disease took hold throughout Australia it reached a peak of 537 daily confirmed cases on 22 March but has since steadily declined with the daily rate of confirmed new cases falling to about 10. By early May about 6,780 cases had been reported resulting in 93 deaths, with a low morbidity rate of 1.3%, and importantly 5,600 persons had recovered.

Ruby Princess

The Ruby Princess (yet another from the infamous Princess Line) returned to Sydney from a cruise to New Zealand. On this voyage it has been reported that 158 persons needed medical attention including 13 with high temperatures. It has since been revealed samples taken from the 13 persons had been sent to Wellington for examination with three testing positive to SARS type fever.

In Sydney on 8 March there was the usual hectic and rapid turnaround with the ship at capacity with 2,647 passengers, departing later that day for another two-week New Zealand cruise. Part way through the cruise, after a visit to Napier on 14 March, the New Zealand Government announced that all passenger ships were banned from visiting its ports with immediate effect. It is suspected that the ship’s visit to Napier resulted in the disease being introduced there and linked to 19 cases.

The next day the Australian Government made a similar announcement but allowed scheduled in transit voyages to continue. With its voyage cut short Ruby Princess headed for Sydney arriving two days early, again with 124 persons reported sick during the voyage, 24 with high temperatures. Without any precautions, other than being advised to self-isolate for 14 days, 2,647 passengers were allowed to disembark on 19 March. The number of cases of the virus thought to have emanated from passengers and crew in this ship reached over 800 (including 190 crew – 12 in NSW hospitals) resulting in 21 fatalities, making this the deadliest known of all cruise ships and the biggest single source of the disease in Australia. In addition to the associated New Zealand outbreak it is believed 35 American and Canadian passengers who returned home contracted the disease whilst on board Ruby Princess and one has since died.

After this incident Ruby Princess remained at sea off the NSW coast while a blame game of ‘who said what and when’ was played out between Carnival Cruises and the NSW Government. The ship was visited by officers of Border Force and a medical team from an outsourced provider to the ADF ‘Aspen’ to assess the health of those on board. The seriousness of the case led the NSW Government to order a police and coronial enquiry, and on 6 April the ship, with about 200 crew showing symptoms of the virus, berthed at Port Kembla. NSW Police Commissioner Mick Fuller says the main focus of a criminal investigation is on whether the operators of the Ruby Princess breached biosecurity laws in failing to alert local authorities to the extent of sickness on board. A statement by NSW Police of 14 April says the initial source of the disease is believed to have been a crew member working in the galley.

In addition to the police and coronial inquiry, now expected to take much longer than originally anticipated, on 15 April the NSW Premier, Gladys Berejiklian, announced the establishment of a special commission of inquiry under the prominent jurist Bret Walker SC. The Ruby Princess debacle has the potential to be one of the worst maritime disasters of the modern age, which through mismanagement both ashore and afloat, was allowed to occur on our watch within waters under our jurisdiction. There appears an unfortunate tendency to treat these events as security incidents whereas they are primarily of an epidemiological (medical) nature. After discharging about half of her crew, to be flown to their respective homes, Ruby Princess finally departed Port Kembla on Thursday 23 April making for the Philippines.

Other Cruise Ships

With a number of cruise ships in Australian waters diplomatic efforts were made by the Australian Government to have these removed, but to where? Eventually, with agreement between the major shipping companies on 5 April surplus crew members were ferried between the various ships in the Sydney region into two vessels which then departed – one bound for India and another for the Philippines taking the majority of stranded crew members home.

In Western Australia the situation remained fluid. On 27 March Cruise & Maritime Voyages Vasco da Gama berthed in Fremantle with about 800 passengers, 200 from Western Australia, 500 from other States and 100 from New Zealand. Passengers were placed in 14 day quarantine with those from Western Australia going to Rottnest Island which had previously been used as a camp for enemy aliens during WWII. Those from other States were sent to Perth hotels and New Zealanders were flown home.

Another independent cruise operator of Artania alongside in Fremantle managed to fly most of its 850 passengers home but 12 sick passengers remained on board in quarantine together with her 460 crew, 79 of whom tested positive to COVID-19. Subsequently three died while hospitalised. After a three-week standoff the ship sailed on 18 April leaving 50 crew members behind who were later flown home. Some 219 of the 550 cases of COVID-19 in WA have been linked to cruise ships.

Just as Titanic taught us that mighty and well-found ships are not unsinkable this virus leads us to question the vulnerability of modern day mighty ships. A thorough technical evaluation may be appropriate into the design of large cruise ships and ultra large warships, especially their mechanical ventilation systems, to ensure they are fit for purpose in preventing cross-contamination in cases of contagious diseases. It is also time to for leading nations with much at stake, such as the United States, to evaluate the operations of the largely self-regulated cruise ship industry.

Technology to the rescue

There are about 1.4 billion people in China and nearly all have cellphones as the Government requires all persons over a certain age to register social security accounts and bank accounts together with mandatory facial scans to identify the user of the phone. On 10 March 2020 the Government furthermore launched cellphone-based health codes which must be installed and registered with personal health information. These generate a code which appears in three colours classifying the user’s health status. Red means the person has an infectious disease, yellow the person might have a disease, and green means the person does not. Use of this system will be obligatory to all users of public transport and by passengers intending overseas travel.

In the meantime, the Australian government is trying to persuade its citizens to voluntarily embrace a new contact tracing phone application ‘COVIDSafe app’. Based on a Singaporean tracing system the new app logs every user who has been within 1.5 metres of a person for 15 minutes or more by using Bluetooth technology to record a digital ‘handshake’ with other phones. Authorities are having problems convincing citizens that this information is secure and only used to help halt the spread of COVID-19.

Summary

History provides many examples from which lessons might be learned. Great plagues or pandemics appeared in cycles with 800 years between the First and Second Pandemics and a further 550 years to the Third Pandemic. With the present COVID-19 outbreak, which we might term the Fourth Pandemic, the cycle has greatly diminished with a little over a century separating this from its predecessor. While in the early stages of this pandemic hopeful signs are emerging that, at least in its first wave, the devastation in comparison to its peers is relatively minor with a little more than 3 million contracting the disease resulting in over 210,000 deaths. Again, in comparison with times past where many millions perished, without appearing insensitive this is historically insignificant.

The Third and Fourth Pandemics both originated in China, the earlier taking many years to escape beyond national borders, but when it did, it spread widely and quickly throughout the world causing devastation which occurred in waves over 50 more years. The present pandemic escaped beyond national borders in a few months and within weeks was spreading throughout the world. Much of this is explained by modern communication and rapid transport making geographic borders almost irrelevant.

As the epidemiology of COVID-19 remains elusive, a medical cure or provision of a vaccine so far remains beyond the panacea of medical science. In the meantime, we resort to the well-tried 14th century system of quarantine and hospitalisation which is proving effective against an unseen enemy which can humble the most scientifically advanced societies, including their military forces.

Measures now implemented such as closing external and inter-state borders, and the closure of universities and schools, churches, cinemas and theatres, sporting venues, shopping centres and other meeting places are but short-term solutions. They result in thousands being out of work with unsustainable economic consequences. As an island nation isolation is a relatively easy option but a lack of self-sufficiency ensures this is only of a limited duration and a strategy beyond containment is necessary. Restrictions will have to be eased in finding a way out of this morass. As in previous cases recovery will be painful and slow.

In national emergencies governments are called upon to take higher levels of responsibility and controls. The Commonwealth and State Governments have been responsive to the emergency, having the advantage of just coming through a series of natural disasters brought about by drought, floods and fires which has seen various levels of government working effectively. Public health systems are much more advanced and better able to deal with emergency situations. Globalisation is now being questioned with diversification viewed as a more appropriate response. We cannot afford to just return to the way things were but should seize the moment, with inspirational leadership, to search for new opportunities beyond limited horizons.

References

The Bible, Second Book of Moses (Exodus) Chapters 7-11, The Bible Society, London, 1952.

Bramanti, Barbara, Dean, Katharine, R., Walloe, Lars & Stenseth, Nils, Chr., The Third Plague Pandemic in Europe, The Royal Society, Proceedings Biological Science No 286, Published online 17 April 2019.

CDC Yellow Book 2020, Chapter 8 – Cruise Ship Travel, US Department of Health & Human Services Center for Disease Control & Prevention, Atlanta, GA., 2019.

Defoe, Daniel, A Journal of the Plague Years 1665, eBook Project Gutenberg, 1995, www.gutenberg.org.

Grey, LEUT Francis, Temple, Influenza in Samoa, British Medical Journal, Vol 1, p 359, 1919.

Handbook for Management of Public Health Events on Board Ships, World Health Organisation, Geneva, Switzerland, 2016.

Henderson, John, Florence Under Siege: Surviving Plague in an Early Modern City, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2019.

McLane, John, Ryan, Setting a barricade against the East Wind: Western Polynesia and the 1918 Influenza Pandemic. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand, June 2012.

Jeppesen, LCDR J. C., Constant Care – The Royal Australian Navy Health Services 1915-2002, Australian Military Publications, Sydney, 2002.

Roe, Jill (Ed), Social History in Australia – Some Perspectives 1901-1975, Cassell, Sydney, 1976.

Updated from media releases of WHO and other websites.