- Author

- A.N. Other

- Subjects

- Ship design and development, Naval technology, WWII operations

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Canberra II

- Publication

- September 2019 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By R. W. Madsen

This paper was prepared largely from notes made many years ago when I was at university and living with my grandparents. My grandfather, Sir John Madsen, lived in the Sydney suburb of Roseville.

John Percival Vaissing Madsen (1879-1969) studied both science and engineering in the fields of radioactivity and X-rays. He was awarded a doctorate in 1907 which led to a lectureship in engineering at the University of Sydney, where he became an Assistant Professor in 1912. During WWI he was commissioned into the AMF and commanded the Engineer Officers’ Training School at Moore Park. He returned to university as Foundation Professor of Electrical Engineering and developed a long and fruitful association with the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. During WWII he led Australia’s contribution to the Allied development of radio direction finding and air warning systems. In 1941 John Madsen was knighted for his services to science.

Introduction

John Madsen was involved in radar support for the Allies in the South West Pacific Area (SWPA) following visits he made to London and Washington in 1940. In 1941 the Radio Physics Laboratory (RPL) in Sydney became a defined sub-centre responsible for research and support to Great Britain.

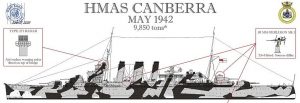

Prior to leaving for Guadalcanal in July 1942, both HMAS Canberra and USS Chicago required work on their radars. Canberra did acceptance trials on a Type 290 Air Warning Set in conjunction with her Type 271 10 cm microwave surface search radar. Chicago had a CXAM Air and Surface warning set with Sir John assisting in its maintenance. In July 1942, RPL gave a demonstration to the RAN of a Type A271L 10 cm set at South Head which under excellent propagation conditions detected a 6,000-ton ship at 45 miles.

In an action on a dark humid night at Savo Island on 8-9 August 1942, Canberra, leading Chicago on a screening patrol at 12 knots, was attacked with 8‑inch armour piercing shells by several Japanese heavy cruisers. With no warning or ranging from her 271 set and without firing a shot in reply, Canberra was disabled in the space of three minutes. Chicago was hit in the bow by a Long Lance torpedo and taken out of action. It is believed that Chicago’s radars at this time were not in continuous operation. The Japanese cruisers then turned north towards a second US cruiser screening group which was engaged and destroyed, overwhelmed by the surprise and the accuracy of the Long Lance torpedoes and 8-inch AP shells.

In addition to surface warning radars the US cruisers in the Northern Group also had fire control radars which gave accurate ranging. The Japanese cruisers did not go on with an attempted destruction of the 19 transports of the US Amphibious Force which the Allied cruisers were screening.

HMAS Australia, with the light cruiser HMAS Hobart, a veteran of the Japanese night action at Java Sea, were on another screening patrol 11 miles to the east of Savo Island and were not attacked that night. They remained with USS San Juan, with SG 10 cm radar, as the remaining cruiser defence of the Transport Fleet. The radars on Australia and Hobart at this time did not include the Type 271, but Australia later had the updated Type 273.

A reconnaissance flight by a B-17 with Air to Surface Vessel (ASV) radar had been requested for the northern approach to Guadalcanal on the afternoon of 8 August, but this was not carried out and the eight ship Japanese cruiser force remained undetected until only minutes before attacking Canberra. Two US destroyer radar pickets, US Ships Blueand Ralph Talbot, with surface warning radar (Type SC), were on patrols seven miles west of Savo Island steaming at 12 knots. The patrols of these ships had become unsynchronised so that when they reversed course at 0110 the gap between their paths had increased. When the Japanese cruisers passed between them at 0132 the gap was 14 miles and they passed without being detected. Using giant binoculars, the lead Japanese cruiser Chokai first sighted Blue at a distance of about five miles at 0054. The nearest point Ralph Talbot came to the Japanese cruisers was 6.5 miles.

Radar Development – US Navy to April 1942

The Naval Research Laboratory (Radlab) in Washington oversaw USN radar equipment developments. The first production radars delivered to the USN in 1940 were the CXAM and CXAM-1, these were air and surface warning sets. Chicago and CVs Saratoga, Enterprise, Wasp, and Curtiss, a seaplane tender, were fitted with this 1.5 metre equipment. The SC metre wavelength warning radar was developed for smaller ships. Fire Control radars FC and FD at 40 cm were installed from September 1941.

The first 10 cm microwave search radar for the US Navy was the SG developed by Radlab and Raytheon in June 1941 and proved to be one of the most successful radar sets, with the first installation going to sea in April 1942. Saratoga and San Juan had the second and third sets put into operation.

US Navy Guide to the Tactical Use of Radar-March 1942

On 9 March 1942 the C-in-C of the US Fleet issued Radar Bulletin No 1 setting out guidelines on ‘Tactical Use of Radar’. It was acknowledged that radar equipment was continuously undergoing improvements and officers and men associated with it should feel they had some latitude in exploiting its use; the bulletin was a guide for improvement after further experience afloat.

The bulletin covered radar use in aircraft carriers, surface vessels and submarines operating in conditions against Germany and Japan in the Pacific and warned of numerous limitations of navy equipment. The points addressed included:

- Trouble from hasty installation; above a basic 50 hours training, many more hours were needed for operator proficiency

- Reduction on operator strain, with two operators to alternate every half hour over two hour watches

- A scarcity of IFF making ship identification difficult. The enemy could pick up radar transmissions at 250 miles and measures should be taken to reduce this risk

- Keeping a good lookout was essential, even though radar was being used

- False contacts may be obtained from ionised layers, most commonly around mid-day, and that at night there would be insufficient time to determine that a signal is false

- The effectiveness of radar relied on data and orders being passed to the ships concerned in a minimum of time.

The bulletin set out that the Officer in Tactical Control (OTC) was to give orders determining which radar policy was put into effect and that in relation to Radar Guard Ships, the assigned responsibility should be the conduct of a continuous search of a sector using counter RDF measures or such radar control as the OTC may order. It was envisaged that each Radar Guard Ship would search an entire 360 degrees and that when a target enters the sector overlap between adjacent sector Guard Ships, the Guard Ship whose sector the target is leaving notifies the Guard Ship whose sector it is entering. It was recognised that Talk Between Ships (TBS) was the only means then available for rapid communication between ships and was to be put in large ships asap. By using low power at 60 mcs the range was anticipated to be 100 miles.

As a radar policy it was suggested that the following could be considered:

- Radar transmissions only to be made when air-surface attack is imminent

- Carry out a sweep every 10 minutes

- Have no restriction on transmissions when the ship’s location was obvious to the enemy or for transmissions to take place using counter RDF measures.

A Radar Operator’s Log for each set was to be kept including details of the following: the radar policy in effect at all times; other general instructions given to the radar operator; time of commencement of transmission and time ceased; irregularities with the equipment; all unusual observations with the radar; name of the operator and time of start/finish and all initial detections and final observation of each target; time for a CXAM/SC sweep through 360 degrees and not taking counter RDF measures. No specific directions for counter RDF measures should be given, but considerable latitude allowed by following the general rule that the radar transmitter be used for the shortest possible time consistent with an effective search.

Ranges with properly functioning radar equipment generally were more reliable than those obtained by ordinary coincidence or even stereoscopic rangefinders and it was of the utmost importance that all ships’ radars be maintained in perfect operating condition at all times, particularly for ranges greater than 10,000 yards. Optical bearings were always more accurate and reliable than radar bearings and should be used in preference to them.

With CXAM, CXAM-1, FC and FD the reliable range for surface ships was between 5 and 10 miles depending on the size of the ship. SC range was 4 to 10 miles. The antennas were always to be installed at the highest possible points of the ship.

Radar Equipment available at this time

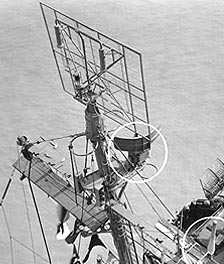

CXAM: 1.5 m Air/Surface search, U frame antenna, 14 miles range on a large ship, 50 miles on aircraft.

CXAM-1: 1.5 m Air/Surface search, Mattress array 15 ft x 15 ft 8 inch, 68 miles on aircraft.

SC: 1.36 m, Air/Surface search, Mattress array 8ft 6 in x 7 ft, 4-5 miles on cruiser, A scope.

FC: 40 cm, Fire Control for cruisers, V mesh array, 10 miles range, A scope.

FD: 40 cm, Fire control for destroyers, pair of U mesh for array, 10 miles, A scope.

SG: 10 cm, Air/Surface search, single parabola, 17 miles on destroyer, 9” PPI, 5” A scope.

Type 271: 10 cm, Air/Surface search, Perspex Lantern, parabolas, 17 miles on destroyer.

Type A290: Surface Warning/Gunnery, 1.5 m.

ASV MkII: Airborne Air to Surface Vessel based on UK set adopted by US and Australia, 1.5 m.

Operations at Savo Island 7-9 August 1942

A Liberator AL 515 fitted with ASV Mk II flew one of the first reconnaissance flights over Guadalcanal in late June 1942 from Garbutt Field at Townsville. Other Liberators, AL 570 and AL 573, probably also fitted with ASV, flew reconnaissance missions to Guadalcanal in July and August. The unit photographer Norman Carlson produced 12,000 prints for preparation of mosaics for the marines and navy before the landings at Guadalcanal on 7 August.

On 31 July 1942 an aircraft from Curtiss (AV-4) at Espritu Santo obtained an aerial photo of the Lunga Point Airfield, Guadalcanal Island. The Japanese had installed a Type II search radar, which when captured was the first example of Japanese radar taken back to the US for examination. It was not until 2 September that the US installed the first Type SCR-270 radar at Henderson Field, followed soon after by two Type SCR-270 AW.

The US Amphibious Force, the first of its type ever assembled, with great speed (but lacking in communication co-ordination), including 20 trans-ports, was able to achieve complete surprise at Guadalcanal on the morning of 7 August having sortied from Fiji over the previous two days without being detected. The Japanese radio traffic analysis had suggested that a major US Naval group had formed in Hawaii but was in fact 3000 miles nearer in Fiji.

At 1325 and 1500 on 7 August the Japanese made two attacks on the transports with bombers and fighters from Rabaul which were broken up by CV fighters located approximately 70 miles to the south west. With warning from Australian Coastwatchers on Bougainville, there was another raid which disrupted the unloading from transports. At 1830 on 7 and 8 August the Fire Support and Screening ships took up their night dispositions along with the transports, and during the 8th marines came ashore to take Henderson Field. At about this time Admiral Fletcher decided he would withdraw the carrier air support one day earlier than was planned on 9 August and that the transports, which were only partly unloaded, would also have to leave but this was delayed by one day after the loss of the air cover. Rear Admiral Crutchley (an RN officer on loan to the RAN) in Australia left his night screening position around 2100 on 8 August to confer on these new arrangements at the poorly equipped command ship McCawley. This left Canberra and Chicago in the Southern Screening Group covering the transports and US Ships Vincennes, Astoria and Quincy remained in the Northern Group with destroyer escorts. The two radar pickets Blue and Ralph Talbot were on the western side of Savo Island with special instructions that if a target was detected warning was to be given and that the target should then be ‘shadowed’.

Reconnaissance by an RAAF Hudson from Milne Bay with no ASV (the Hudson crew was not aware of the operation underway at Guadalcanal because of a secrecy embargo) at 1025 on 8 August indicated that a Japanese force of eight ships located on the eastern side of Bougainville was heading south and appeared to include a seaplane tender. This report was broadcast from Pearl Harbour on Fox and reached Admiral Turner in Guadalcanal at 1845, it was also broadcast on Bells from Canberra at 1817.

This force had been detected the previous day by a US submarine. A requested reconnaissance flight by a B‑17 for the afternoon of 8 August to cover the area from the northern end of the ‘Slot’ leading south to Guadalcanal was not carried out as an enemy night attack was not envisaged. It was expected that an extensive air search during 8 August would reveal any enemy naval forces heading for Guadalcanal.

At 2345 on 8 August Ralph Talbot detected by radar an unidentified plane flying low over Savo Island heading east towards Tulagi and broadcast on TBS and TBO (portable voice radio) ‘Warning! Warning! Plane over Savo Island heading East’ which was heard by the destroyers Blue and Patterson, the cruisers Vincennes and Quincy and some others. At 2313 the Japanese had despatched two planes to illuminate a course for the cruisers to ‘rush in’ and had previously used scout planes to confirm the Allied Forces disposition. They then developed their tactic of destroying one group first, and then going straight to the second group, and leaving to be clear of Allied planes by sunrise, making no special plans to attack transports.

At 0053 the lead cruiser Chokai sighted Blue with giant binoculars at 10,900 yards and turned to enter from the north passage, but at 0105 reverted back to ‘Enter from South Passage’ realising that she had not been detected by Blue or Ralph Talbot. Blue was lost at Guadalcanal on 22 August 1942.

It would appear that Chokai, leading the column of Japanese cruisers and still undetected, sighted Canberra and Chicago at 12,500 yards around 0132-0136 on 9 August. Japanese 120 mm binoculars used with the larger 150 mm giant Navy Nikon binoculars detected 980 times as much light as the naked eye. Spotters were carefully selected for good night vision and crews were drilled to use flares and searchlights. Some 23 spotters were located on a cruiser.

At 2300 on 8 August, David Medley, Canberra’s young radar officer, visited the 271 radar station and found everything apparently working well. Since sunset all six radar operators had been on four hour watches, two men at a time working half hour tricks. The set was working normally but they were still having trouble with masking from nearby land but with the large number of vessels in working range it was practically impossible to tell friend from foe. Occasionally Canberra saw Blue and Canberra’s escort but if they came in too close they disappeared. Canberra could not see any ships in the Northern Group.

David Medley, a Masters graduate in physics from Melbourne University in 1941, had an interest in ham radio which led him to reply to an RAN advertisement for scientific people to join the navy to work on radar. His first task was to assist at Garden Island while Canberra was having a three-month refit and help to install the Type 271 and Type 290 radars. By the end of May Canberra was back in Sydney after a shakedown cruise to the Melbourne area where two magnetrons were provided to get the 271 working. The essential part of the work for Medley was to try and get the 271 integrated into the ship’s gunnery systems but first he was required to do the calibration work and then later to consider the tactical use of the radar; however at Guadalcanal the Captain and senior officers were not hopeful of the 271 being of any use. There was no telephone communication from the 271 to the bridge, and at the time of the Japanese contact there was no senior officer on the bridge. The scope of the 271 was a 6-inch CRT with range read off the scope and bearings determined from the ship’s head as there was no gyro compass in the radar hut. The aerial was rotated by hand and was located immediately above the transmitter.

In Canberra at about 0100 a plane was heard and this had been reported to the captain. At 0143 an explosion occurred due north, the captain was called and the ship went to Action Stations. Patterson at this time broadcast a TBS ‘Warning! Warning! Three strange ships entering the harbour’ but apparently this was not received in the majority of ships. Within Canberra in the next few minutes, events moved very quickly; while avoiding torpedo tracks across the bow and approaching down the starboard side, a salvo of shells hit the bridge, mortally wounding the captain and other officers, flares dropped by aircraft lighting up the scene. Between 0144 and 0148 Canberra was hit by 24 shells (AP). The ship quickly lost power and listed to starboard. Canberra’s guns were pointing to the port side but she did not fire any rounds. In the confusion it is possible that Canberra was hit by a torpedo on her starboard side fired from USS Bagley.

Canberra was scuttled in the early morning of 9 August. Captain Frank Getting, RAN, later died of wounds, and 84 of his ship’s company were lost. In hindsight, with a better understanding of her damage and what could be done for her in Sydney, she might have been saved.

Chicago was hit in the bow by a torpedo and she veered away to port, but neither Chicago nor Canberra alerted the northern Vincennes group of the Japanese action.

At 0137 Chokai sighted Vincennes in the Northern Group at 18,000 yards (the greatest distance at which visual sighting was reported during the action) and at 0150 Vincennes obtained a radar range on Chokai of 8,250 yards identified by the intermittent use of searchlights by the Japanese to pinpoint the three US cruisers. At 0151 Quincy obtained a range on Aoba using a stereoscopic range finder at 8,400 yards. Repairs to Astoria’s fire control radar had been successfully completed just prior to contact with the Japanese and at 0152, while waiting for orders from the bridge, the gunnery officer made a quick radar check of the report and observed four pips on the forward main battery fire control radar screen. These pips were Chokai, Aoba, Kako and Kinugasa. An initial range of 7,000 yards was obtained on the leading cruiser, which Astoria took as her target. At 0153 the radar range finder range of 6,800 yards on Chokai was correct. At 0155 Astoria was hit and she obtained no more radar ranges and was unable to get visual ranges as the Japanese had turned off their searchlights. By 0159 Astoria had fired off at least seven salvoes on Chokai which received several hits, some also from Quincy.

The three carriers Enterprise, Saratoga and Wasp approaching Guadalcanal on 5 and 6 August had 200-mile reconnaissance flights looking forward and sideways for enemy ships. The range of CXAM-1 on aircraft was 50-100 miles. For the first time the carriers were given the task of providing cover for a major amphibious landing expected to take three days to complete. On the early morning of 7 August Enterprise was positioned 50 miles SE of Guadalcanal near San Cristobal Island and at one hour before sunrise (0535) the carrier planes launched to rendezvous 30 miles west of Guadalcanal in the dark and then at 0615 the bombardment, aerial attack and marine landing commenced. At 1230 a large unidentified plane was detected and the CAP cover was vectored to the north-west by an error of the fighter director on Enterprise reading the wrong side of the azimuth ring on a radar scope, giving the reciprocal bearing. At 1100 Saratogadetected a bogey by radar to the NW at 150 miles which turned out to be a B-17 from Esperitu Santo on a Sector II reconnaissance. Throughout 7 and 8 August air cover was maintained in the face of two concerted Japanese attacks on the afternoon of the 7th by planes from Rabaul and also a further attack on the 8th, warned by the Coastwatchers on Bougainville. Over the two days Enterprise had 372 take-offs and 366 landings where 91 pilots had flown 1,000 hours. At the close of operations on the evening of the 8th, Admiral Fletcher considered his position was well known to the Japanese and it was time to withdraw his three carriers to the southeast. They were 160 miles away when radios began to announce some kind of surface action was taking place at Guadalcanal. The captured airfield at Lunga Point, Henderson Field did not become operational until 19 August.

As Chokai led the Japanese withdrawal around Savo Island north, Ralph Talbot encountered the cruiser Yubary and fired a second salvo using her radar range of 3,300 yards which was accurate. Ralph Talbot received a second hit in the charthouse which destroyed the SC and FD radars and fire control equipment.

At 0225 on 9 August the damaged Chicago had a radar contact at 7,000 yards; at 0232 Bagley was tracking a ship on her port side and at 0341 she was tracking further targets which probably included Patterson proceeding to pass south of Savo Island.

The SG radar on San Juan did not report any radar contacts during the night action and at 0911 on the morning of 9 August her air search radar detected a Japanese reconnaissance plane at 12 miles which remained unmolested for an hour before disappearing at 1004, having reported the presence of 19 transports. At 0700 Saratoga had detected search planes which disappeared at 0743.

Events Subsequent to Savo Island 7-9 August 1942

Following Coral Sea and Midway the third and fourth carrier battles were in the Guadalcanal campaign at the Battle of the Solomon Sea (24-25 August 1942) and the Battle of Santa Cruz Islands (25-27 October 1942). Aerial reconnaissance was out to 200 miles with radar plots by Enterprise of raiders out to 88 miles, but on occasions at 50 miles on the CXAM-1. A large four engine flying boat had been detected at 55 miles. The problem with radar plots was to differentiate between friendly scouts and raiders.

The naval Battle of Guadalcanal (12-15 November 1942) was two night actions against the desperate Tokyo Express runs. At 0124 on 13 November, the light cruiser USS Helena detected Japanese ships with her radar and in the ensuing action USS Atlanta was sunk along with four destroyers. Two days later, on the night of 14-15 November the battleship USS Washington, with the effective use of her radar (CXAM-1 and five Fire Control radars), managed to avoid the crippled USS South Dakota and fired 16 inch shells at 8,400 yards, destroying the Japanese battleship Kirishma, which had to be scuttled. The loss of Kirishma was a turning point for Japanese radar when it was realised how significant its use had been in this defeat. (At the Battle of the Bismarck Sea on 2-4 March 1943 the Japanese attempted to reinforce Lae from Rabaul with a convoy of eight destroyers and eight transports but it was decimated after radar and decryption detection preventing further reinforce-ment into New Guinea.).

Two weeks later the US set a trap for an anticipated Tokyo Express run. The US Navy had two cruiser forces and one destroyer force with one SG equipped ship in each force. At 2306 on 29 November the Japanese were detected on radar, and at 2316 the destroyer USS Fletcher had enemy ships at 7,000 yards on SC but not following the plan she was not given permission to fire her torpedoes. Admiral Tanaka quickly counterattacked with Long Lance torpedoes from his destroyers on the four US cruisers, Minneapolis, New Orleans, Pensacola and Northampton. Three of the cruisers were severely damaged and one sunk. The Japanese ships escaped but without landing the desperately needed supplies.

Chicago was lost to an aerial torpedo attack at night on the 30 January 1943 where bright floating flares allowed a twin engine bomber to make an approach in darkness. The Japanese finally cleared their troops from Guadalcanal by 7 February 1943.

Canberra had the first 10 cm magnetron Australian radar to go into service, even though it was only for a very short time. The Type 271 was fitted to Australian destroyers and corvettes along with the Type 290, which came into service during 1942-43. Many of the damaged US cruisers from the Guadalcanal campaign made their way to Garden Island in Sydney for immediate repair before returning to the US.

In addition to the many US ships, as well as Canberra, which were sunk off Guadalcanal, a great many aircraft were lost in air battles defending Henderson Field, and the area now known as ‘Iron Bottom Sound’ has become sacred to the US Navy which each year makes a solemn pilgrimage to remember those lost.

Conclusion

This paper highlights the radar aspect of its implementation into the first major amphibious operation by the US in the Pacific War. This provided many lessons for subsequent operations leading to the eventual defeat of Japan in the SWPA and finally to Japan itself. The isolation of Rabaul and debilitation of the Japanese air force planes and navy due to the twin attacks by the Allies in the Solomons and New Guinea was finally achieved by the US carrier borne attacks on Truk in February 1944.