- Author

- Dunne, Mike

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- March 2006 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

In the meantime Tanaka began ferrying General Hyakutake’s men and materiel to Guadalcanal to retake the strategically important airfield.

On the night of 17/18 August nearly 1,000 Japanese troops were landed by high-speed transports escorted by seven fleet destroyers. Their speed was just sufficient to be in and out again within the hours of darkness and their nocturnal activities were to become so regular as to be named the ‘Tokyo Express’.

For a week the enemy ran in small parcels of troops to build up the strength to take the island, but even at this early stage they had to work by night as American air cover by day was too great a threat. In the early hours of 22 August the destroyer USS Blue (one of the pickets so ineffective a fortnight previously at Savo) was one of two radar-equipped ships sent to interdict the Japanese. Again they were surprised and the ship was heavily damaged by torpedoes from the DD Kawakaze. She was later scuttled and the enemy had claimed first blood.

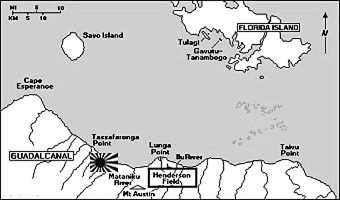

On 24 August the enemy tried direct assault. While the inconclusive Battle of the Eastern Solomons was being fought between the main fleets to engage the American presence, a bombardment force of four destroyers under the redoubtable Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka ran a group of transports down ‘The Slot’, the long channel dividing the double chain of the Solomons. The destroyers duly ‘softened up’ Henderson Field but had a transport set afire and the destroyer Mutsuki disabled because she dallied too long and was caught by daylight. The landing was called off and the Mutsuki scuttled.

By working out of the Shortlands Tanaka was just beyond the range of the Henderson-based Douglas SBD bombers yet just able to complete a smart return trip in the dark hours. Thus three destroyers landed 350 men on the night of 26/27 August and 130 more on the following night. Overconfident, the Japanese then left too early on the next trip and were caught at dusk, losing the Asagiri, her embarked troops and their supplies.

It became the custom for the enemy destroyers, once their supercargo had been rapidly offloaded, to spend a few minutes lobbing a valedictory salvo or two into the airfield perimeter. On 5/6 September the American destroyers USS Gregory and USS Little tried to interfere and were both sunk for their troubles.

By mid-September the situation ashore was stalemated, neither side having the strength to displace the other. The Japanese high command then made Guadalcanal a top-priority goal, withdrawing the all-important destroyers in rotation for modification. Stowage and AA weapons were increased for the loss of some main battery guns. Torpedoes were retained.

Loss of USS Wasp

Supplemented by pottering Daihatsu barges, the destroyers built up the Japanese strength for an offensive. With the Americans in greater strength than anticipated, this was not easy, the destroyers having to run in urgently needed replacements. Meanwhile, the Americans landed 4,000 more marines, but at the cost of the carrier USS Wasp and a destroyer from the covering Carrier Task Forces.

I-19, Lt. Cdr. Takakazu Kinashj, fired a salvo of six torpedoes at CV USS Wasp. Two hit the ship, starting gasoline fires which doomed the ship. The other four torpedoes went on another several thousand yards and encountered another US Task Force, hitting and severely damaging the BB USS North Carolina and sinking the DO USS O’Brien.

It took the USN a long time to finally accept that this one devastating torpedo attack was the work of one submarine.

During October Tanaka’s destroyers worked miracles, the nightly runs of the ‘Tokyo Express’ delivering 20,000 men with equipment. Henderson-based aircraft were a continuing aggravation and heavy cruisers came down on the night of 11/12 October to bombard the airfield. They ran straight into a superior American force that had been covering one of their own landings. In what became called the Battle of Cape Esperance the unsuspecting Japanese had their ‘T’ crossed and lost a cruiser and a destroyer. Two destroyers from the ‘Express’ were also sunk by aircraft at first light.

Determined to reduce Henderson, the Japanese bombed it heavily twice in daylight on 13 October, interfering with repairs to cratered airstrips by artillery fire. After dark they brought down two battlecruisers. In a 90-minute bombardment the airfield was plastered with over 900 rounds of 356-mm (14-in) ammunition. Aviation spirit stocks and 48 aircraft were lost. More bombing on the following day was followed by 150 rounds of 203 mm (8-in) fire during the night from two heavy cruisers. Simultaneously, the ‘Express’ brought in heavy reinforcements in transports, gambling on the parlous state of Henderson’s defenders to tie offshore during the day. Fielding everything that remained, the Americans destroyed three transports and forced Tanaka to withdraw. He returned with heavy cruisers on the night of 15/16 October, laying 900 rounds of 203-mm and 300 of 127-mm (5-in) fire within the shattered perimeter.

Final Assault

Dazed and battle weary, the defenders then had to beat back the Japanese who, from 22 to 26 October, committed everything to what was intended as a final assault. They failed by a narrow margin and Tanaka’s destroyers were given a very damaging reception from artillery when they unwisely assumed from the lack of Henderson cover that it was safe to support the army by day.