- Author

- Fazio, Lieut. V. RANEM

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, History - post WWII

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- HMAS Platypus

- Publication

- March 2023 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

By Vince Fazio

We recently became aware of a proposal to upgrade the Watsons Bay Wharf and have written of our concerns (see Letters) to the Manager of the Project Team with a copy to the Commanding Officer of HMAS Watson. An interesting background is found in the following extract from Monograph 110, written by the late Vince Fazio, and published by the Naval Historical Society in 1987.

At the end of the Second World War, the RAN had many more ships than required for its immediate post-war use. Consequently, ships were ‘paid off’ and laid up at various places around the country, for example: Cockburn Sound in Western Australia, Geelong and Williamstown in Victoria, the Brisbane River and principally, Sydney.

The Mothball Fleet

Famous ships were despatched to the Reserve (or Mothball) Fleet from 1946, including the cruisers HMA Ships Australia, Shropshire and Hobart, along with the destroyers HMA Ships Stuart (I), Vendetta (I) and Q class. Others laid up included River class frigates, Bathurst class minesweepers (the famed corvettes of the Second Word War), the tank landing ships, the boom boat HMAS Kara Kara and of course, the veteran of the two world wars, the depot ship HMAS Platypus.

Early History

This is where the writer comes into the picture. Platypus, berthed at Watsons Bay, was the Headquarters

Ship of the Reserve Fleet. An old and quite quaint ship in a lot of respects, she was acquired initially as the parent ship for the submarines AE1 and AE2. Because both vessels were lost early in the Great War, and as Platypus was not commissioned until 2 March 1917, she remained in UK waters in her designed role of a Submarine Depot Ship, commissioning as an RAN ship on 13 March 1919 (under the command of CMDR E.C. Boyle, VC, RN), when the six J class boats were presented to the RAN. She was a unique ship for her time, fully equipped to maintain submarines via her onboard range of workshops, able to rectify almost all defects of the early submarines within her own capacity.

On 8 April 1919 Platypus and the J boats departed Portsmouth, arriving in Sydney on 15 July, under the escort of the light cruiser HMAS Sydney. She paid off on 12 July 1922 and recommissioned the next day as a Fleet Destroyer Depot and Repair Ship, a role she was to retain for most of her service. Another role was during the time she had the submarines Oxley and Otway under her wing between 16 August 1929 to 10 May 1930. Other missions included that of Target Towing vessel and Fleet Maintenance Ship, with her extensive workshops and equipment. This role was redundant until the 1968 vintage HMAS Stalwart commissioned for the same purpose. The last role for Platypus was of course, Reserve Fleet Headquarters Ship.

Platypus was berthed at Garden Island until 26 February 1941 as a Depot Ship, having been renamed HMAS Penguin for the period 16 August 1929 until that date. She received the name Platypus and was recommissioned into the Active Fleet on 25 February 1941. After initial service as a training ship she arrived in Darwin 19 May 1941 and served as a Base Ship. I think she was credited with shooting down a Japanese aircraft during one raid. On 19 February 1942, she was damaged and the following day signaled all Fleet units: ‘Intention is to hold Darwin’. The signal was repeated on all subsequent raids.

A refit at Williamstown Dockyard kept her out of action from May to December 1943, following which she served in New Guinea waters as a maintenance vessel. At the end of the Second World War, she returned to Sydney and paid off into reserve on 13 May 1946. When she assumed the HQ Ship role is unknown, although it must have been relatively soon after paying off.

A Personal View

When I joined Platypus for fourteen months in April 1954, she was well and truly settled into that function. She was no longer seagoing (just as well), but the ‘old girl’ boasted spacious messdecks, with the officers living in an ‘olde worlde’ atmosphere with polished wooden partitions and louvered doors in their cabins The collection of officers and sailors serving in her could excuse one for thinking that Navy Office, in its infinite wisdom, had decided to match outmoded and redundant ships with men of similar calibre. Real characters, all of them. They comprised a few permanent Navy, with the remainder either RANR or RANVR, seeing out their time until retirement. There was also the ‘Platypus All Stars Rugby Team’ who didn’t need a ball on the ground to play and enjoy a good game. Having drafted in from HMAS Condamineand a stint in Korea, I was not prepared for all of this – but what the hell, if you can’t beat them, join them, so I did.

The shipwrights had a couple of workshops, one of which was a machine shop on the port side of the upper deck and as an added bonus, the wheelhouse was converted to a joiners’ workshop. We took turns at being Captain and Helmsman and although everybody else and the ship herself were blissfully unaware, we were throwing her around like a destroyer and woe betide anybody who got in our way.

I suppose the ‘Ripping Yarns’ adventures were starting to show in our mannerisms and as a result, the Chief Shipwright decided I would be better employed away from such a dangerous environment. So I was seconded to the Mothball Party. This was to prove one of the very interesting milestones in my naval service. The party consisted of a shipwright in charge, an AB, two stokers and myself. The idea behind mothballing was to seal a ship up in the major areas, engine and boiler rooms being usually excluded due to the difficulties involved with such large spaces. The basis for the procedures was obtained from the US Navy, who as it showed, had developed tremendous expertise in mothballing procedures.

Preservation of ships in the Reserve Fleet

We concentrated on the upper deck machinery and fittings and the procedure for such work was to build a birdcage-like structure around the equipment out of 2 x 2 timber, keeping the structure as small as possible to minimise the volume of airspace to be treated. We would glue the timber to the deck where possible to avoid welding; when the framework was completed, it was covered with flywire, leaving an access opening and a window, to which would be attached a humidity meter at the final sealing stage.

Having done that, we then sprayed a glutinous liquid, termed ‘Liquid Envelope’ which was a rubbery silver tinted material. This material was applied using spray paint equipment. From my recollection, the liquid was supplied in 44 gallon and five-gallon drums and was imported from the USA. When all the upper deck equipment and fittings had been sealed, all doors, except one, were sealed and locked to prevent any unauthorised access. The remaining door was left until last to allow access into the main spaces so that the drying agents could be placed where required.

There was no point in sealing the ship unless all air inside could be dried out. This was achieved with a large quantity of silica gel, which was spread out in large metal trays strategically placed throughout messdecks and other spaces. A large percentage over the nominated quantities was always allowed in case there may have been any air leaks that could have been missed during the sealing process. Spreading the gel was always left as late as practicable. Prior to placing it, humidity meters were placed at scuttles where they could be read from a boat alongside, for example. We always filled a drip tray under each meter with silica gel, just as a friendly gesture, you might say, and to ensure a better or more favourable reading! The gel was spread and when all had been inspected to ensure that all was satisfactory, the access opening was sealed and coated with the liquid envelope.

Watsons Bay

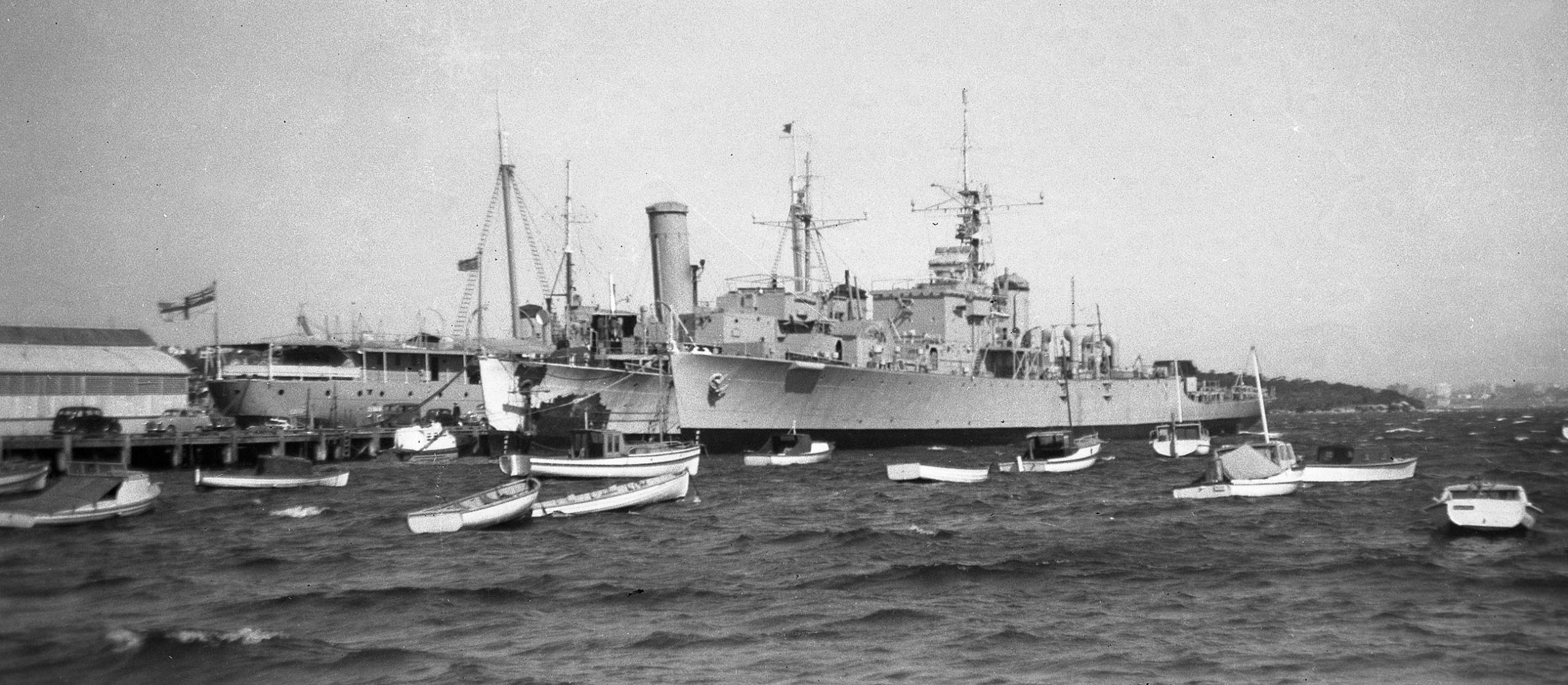

Most of the mothballing, if not all of it, was done alongside at Watsons Bay wharf. The wharf used to be much longer than it is now of course, and the usual arrangement was Platypus and HMAS Shepparton outboard on one side with HMAS Gascoyne on the other side, with the ship to be mothballed stationed outboard of Gascoyne.

This was required because there was no compressed air available such as at Athol Dolphins, where the majority of the Reserve Fleet was berthed. When the mothballing process was completed, the ship concerned was towed to Athol Bight, and another brought down to Watsons Bay where the process was begun all over again.

Finale

I am uncertain whether any of the mothballed ships were ever brought back into service. Ships such as HMA Ships Strahan, Gympie, Shepparton, Dubbo, Bunbury, Bundaberg etc. are all gone now. Besides, they would all be over forty years old and collecting Repat pensions if they were still around!

Although Platypus made her final cruise in 1958, there were many others during her time in the Reserve Fleet. Great excitement was generated when news of the Annual Island Cruise was promulgated with visions of waving palms, etc. The island was Garden Island, and the waving palms were attached to the end of the Dockyard workers’ arms. A stint in the Captain Cook dry dock for a bottom scrape and repaint and then back to Watsons Bay for another year was the extent of the cruise.

I remained in the wheelhouse on one of these cruises and physically had to gag myself to stop from laughing out hysterically, when the Captain and the First Lieutenant arrived on the starboard wing of the wheelhouse calling for cups of kai to be brought to them while we were under way. The old warrior paid off on 1 November 1956, being towed up harbour from Watsons Bay and flying a 360-foot long paying off pennant. The ship remained laid up, serving as the headquarters ship for the reserve fleet, until her sale on 20 February 1958 to Mitsubishi Shoji Kaisha, Tokyo. In company with the corvette Dubbo, she was towed away, reaching Yokohama on 24 June 1958 for breaking up.

As I said earlier, an old and quite quaint vessel, the likes of which we shall never see again. I think that that is a great pity in a lot of respects. Her name was for many years perpetuated at the Submarine Depot at Neutral Bay, which was quite fitting and proper. She served Australia well.