- Author

- Editorial Staff

- Subjects

- WWII operations, History - WW2

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- September 2024 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

The December 2023 edition of this magazine contained an article titled Newcastle Reminiscences, compiled from the recollections of 97-year-old Mrs Thelma Tame. Her uncle was the late Major William Sticpewich (pronounced ‘Stipperwitch’) who played a prominent part at Sandakan.

Singapore to Sandakan

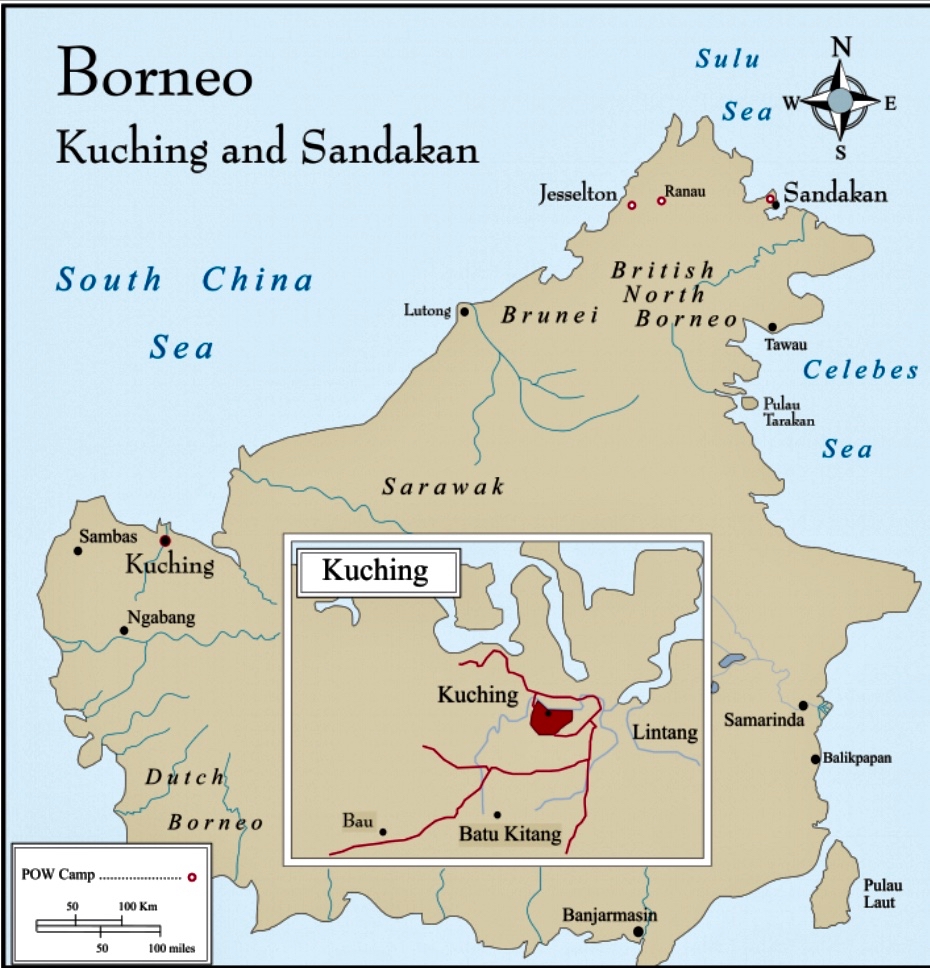

In Australian historical terms, Sandakan is a military campaign which hardly rates a mention in naval history, although the associated battles of Balikpapan, Labuan and Tarakan all feature in the naval lexicon, with ships being named after these associated landings late in WWII.

These events occurred in the northern part of the vast island of Borneo, the world’s third largest island. Before WWII much of this remote region, known as British North Borneo with its capital at Sandakan, was largely unexplored and covered in inhospitable jungle where Europeans feared for their lives from tropical diseases. However, Sandakan should not have been unknown to Australian authorities as its harbour had been used as an RAN destroyer base from June 1915 to December 1916 when these ships patrolled in search of vessels supporting German intrigues against British commerce.

In 1929 large oil reserves had been discovered in British North Borneo with production beginning a couple of years later. With the Japanese thrust through Indo-China it was not long before the whole of the East Indies, including Borneo, was invaded with its valuable resources redirected to assist the Japanese war machine.

With the fall of Malaya and Singapore in February 1942 the Japanese unexpectedly received over 80,000 mainly British, Australian and Indian POWs into their custody. This presented a costly logistical problem. Initially the Japanese had few plans for the POWs who were allowed considerable freedom within the confines of their camps, with discipline controlled by their own officers. Guards were strict but not too controlling and at first food was reasonably available, providing the inmates adjusted to Asian diets. Working parties were used outside the camps in clearing damaged property and again given considerable freedom, leading to some looting, which Australians termed scrounging or ‘making best use of discarded property’.

Possibly because of a large headquarters element the Allied troops in Singapore tended to be over-officered which also extended to NCOs. This led to many drones and insufficient workers. Officers remained entitled to batmen which irked many junior ranks, and they were not expected to be engaged in physical labour, which did little to enhance morale when hands were short. However certain officers did what they could to improve conditions by organising sports, games, concerts, etc.

To make prisoners productive rather than a burden the Japanese arranged for them to be relocated to Japan and other controlled territories as unskilled factory and mine workers. In addition, workers were also deployed to the building of the Thai-Burma railway and to tame the jungle of Borneo and build airfields.

To gain volunteers for these ventures the Japanese painted rosy pictures of these projects – those who gave freely of their labour would be well housed and well fed, provided with clothing and even paid a small allowance with which they could obtain extra rations and luxury goods. So it was not too difficult to encourage 3000 prisoners who were not doing very much at Singapore’s Changi to ‘volunteer’ for Borneo.

A total of 2428 prisoners (1787 Australian and 641 British) were transferred from Singapore to Sandakan by ancient steamers. As these were mostly volunteers a high proportion of officers and NCOs ensured their names were on the list. The officer in charge of this group was Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Walsh, an artilleryman chosen by the Japanese as he was not seen as a popular leader.

The first shipload of 760 Australians with luggage and rations was taken from Keppel Harbour in the coal-burning coastal steamer Yabi Maru on 7 July 1941 in primitive conditions lacking sanitation on a ten-day voyage to Sandakan. On first sight the settlement was stunningly beautiful, spread along the foreshore of a magnificent harbour with opulent homes used by wealthy European residents, where now the Japanese Rising Sun was flying aloft from all major buildings.

The prisoners were marched to their new home about 15 km inland where they had to help build their compound and then undertake backbreaking work constructing a new airfield in the most inhospitable of environments.

Living Dangerously

At Sandakan some contact was made with what remained of the local ruling class; these were often of mixed race with unique skills, such as running the power house or providing medical services. Amongst this community, who had lived well under British and Dutch colonial rule, there was no love for the Japanese.

Sandakan was also close to the Philippines where active guerrilla groups supported by Americans were waging an internal war against the Japanese, and within Borneo there was also a small clandestine underground movement, planning action against the Japanese. Some POWs began making contact with the resistance movement but when this was discovered it led to disastrous consequences.

Bill Sticpewich and the Technical Party

William Sticpewich was born on 4 June 1908 at Carrington, which was a working-class suburb of Newcastle, NSW. He grew into a handsome, strong and fearless youngster who pioneered Australian motorcycle racing at speedway stadiums and later raced on the European circuit. Back in Australia he built and raced midget cars which meant he developed considerable engineering skills. When needs required, at the time of the Great Depression Bill had worked in an abattoir as a meat inspector.

Bill Sticpewich was 32 years old when he entered the Army on 19 June 1940 as a private soldier, but after the initial square bashing, in August he was promoted to acting sergeant and by October 1940 he was a warrant officer. Sticpewich had been assigned to the not very exciting Army Service Corps (ASC), providing supplies to our forces in Malaya; he was later a prisoner at Changi before volunteering for Borneo.

There was one hiccup early in Sergeant Major Sticpewich’s rapid rise through the ranks when he was court-martialled, accused of misappropriating government property. With his regiment about to embark for Singapore he was found guilty of a lesser charge and escaped with a fine, but retained his rank. He learned a great deal about court procedures, invaluable when he was later a star prosecution witness.

A group of likeminded prisoners drawn from various trades, such as carpenters, plumbers and electricians, was housed in a large workshop outside the camp gates. Led by Sergeant Major Bill Sticpewich, they were expert at fixing electrical or mechanical breakdowns where improvisation was the name of the game, making spare parts from all sorts of materials. They were also called upon to make coffins, an expanding enterprise.

So good were their services that the Japanese provided privileges. They had separate accommodation to access workshops, were not expected to work on other manual tasks, and were allowed outside the camp, which provided the chance to barter with locals for extra food.

Bill Sticpewich knew how to play this game exceedingly well and became trusted by some guards; he started to learn the Japanese and Malay languages. Did this friendship extend too far and was he compromised? This is a moot subject as many fellow inmates question his loyalty but to others he was a hero. The truth possibly lies somewhere in-between.

In September 1942 when a potential breakout was discovered at Sandakan, ringleaders were beaten within an inch of their lives. All prisoners were assembled and harangued by the commandant Captain Susumi Hoshijima and informed they would be shot if any were found outside the compound. In addition, all officers and men were required to sign a document stating they would not attempt to escape from the camp. LTCOL Walsh refused to sign and he was then roughly bundled away, his future in the balance. A face-saving compromise was reached which allowed the prisoners to sign the document under duress. LTCOL Walsh, whose stocks had gone up with the troops, was transferred to Kuching with a number of other officers and NCOs who had showed defiance.

The new camp commander Captain George Cook was an inexperienced officer not liked by the men. Cook assigned much of the routine administration to the ever-helpful Sticpewich. The relationship between Cook and Susumi Hoshijima was cordial and on occasions both men dined together, leading to suspicions of collaboration. Captain Susumi Hoshijima was a professional engineer first and army officer second and when the airstrip was completed his job was done. In 1943 new guards arrived who were much harsher than the old hands they replaced, and Captain Nagai Hirawa became second in command to Susumi Hoshijima.

The Naval Men

Within the Sandakan Camp of predominantly military men were, surprisingl,y three others who may have gone unrecognised. They were Bandsman Henry (Harry) Alfred Kelly RANR, Able Seaman George Bradshaw Morriss RAN from HMAS Perth and Lieutenant Norman Kenneth Sligo RANR.

Perth was sunk in the Sunda Strait on 28 February 1942, a fortnight after the fall of Singapore. Kelly and Morriss were survivors originally interned at Kuching in south Borneo. On 9 April 1942 they were amongst a group of 20 men transferred to Sandakan to make good the losses through sickness and/or death at the camp. Kelly had originally joined the RAN as a young bandsman in England, first serving in HMAS Australia II and was still a bandsman, aged 41, when he died in captivity on 20 January 1945. Able Seaman Morriss from Frankston in Victoria was only aged 23 when he also died in captivity on 9 May 1945.

Sligo, a New Zealander by birth and now aged 42, was a river boat captain in Malaya who spoke the language fluently. He enlisted in the RNR at the outbreak of hostilities and transferred to the RANR. He was first attached to the Australian Army Ordnance Corps and was appointed as the Sandakan camp’s Intelligence Officer. Through this association Sligo became involved with the local civilian resistance group and in an attempted break out. Tragically Sligo contracted dysentery and died on 31 August 1942; his was the fourth death at the camp.

Building of Airstrip – Conditions Deteriorate

An earlier British survey had planned an airstrip outside Sandakan but the terrain was difficult, with gullies and valleys which needed filling and drainage to ensure the fill was not washed away by monsoon rains. There was an acute lack of mechanical equipment and only a physical POW labour force which proved inadequate for the task. Accordingly, this was augmented by a locally recruited pool of labour and between them, somehow the task was completed allowing Japanese aircraft to use the strip. But soon after the strip became operational the tide had turned and Japanese aircraft were becoming fewer, being replaced by American P-38 Lightning fighter-bombers and then by much heavier Liberators who tore the strip to shreds.

Relocation – New Airstrip

Conditions at Sandakan rapidly began to deteriorate, and with American superiority in the air and on the seas supplies were not getting through. Rations and materials were reduced which affected both the Japanese and their prisoners but in the case of the latter, the rations were reaching starvation levels and there was a lack of medical supplies.

Formosan guards at the camp were brutal and sadistic, taking delight in fierce beatings which often led to death, and Japanese masters showed little interest in the welfare of the inmates. In addition, the Australian senior officers were not held in high regard by the men so morale was at a low ebb.

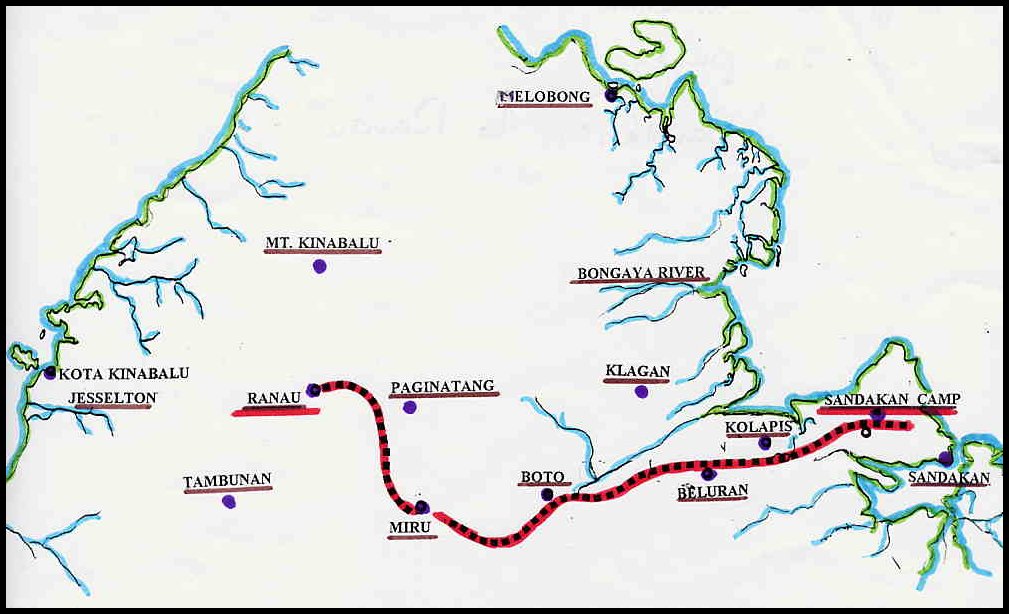

During all this the Japanese high command came up with another plan, to build a new airstrip further afield from advancing American forces. The new airfield was to be constructed at Ranau, some 400 km to the west. Ranau is at the foothills of the magnificent Mount Kinabalu which at 4095 m (13,438 ft) is one of the world’s tallest peaks.

Death Marches

With concerns that American advances in the Philippines would cause Japanese bases in the west of Borneo to be targeted the Japanese set about strengthening these positions. Captain Susumi Hoshijima, commanding the Sandakan base, had been ordered to move 450 troops plus 500 POWs, acting as mules carrying supplies, to a base near Jesselton. Realising that the prisoners were in no fit state to undertake such an arduous task, the CO made a request to Army HQ in Kuching for a postponement to enable them to set up more supply dumps. This request was denied with a curt response to be ready to move without further delay.

The prisoners were informed that their fittest men were to be transferred to another part of Borneo where food was plentiful and those who volunteered would get extra rations, a supply of tobacco, extra clothing and those without boots (most) issued with footwear. With these incentives prisoners clamoured to join this draft.

When the first march began on 28 January 1945 only 452 prisoners could be mustered as fit enough to travel. Each prisoner was expected to carry up to 25 kg of ammunition, food and other supplies. Starting out in groups of 50 with a similar number of soldiers in heavy rain, over treacherous terrain, over mountains, through swamps, it was not long before they were barefoot. Japanese rubber slip-on shoes without socks fell off and were discarded, leading to lacerated feet having to contend with leeches. Swarms of mosquitoes were a constant pest and most suffered from beriberi, dysentery and/or malaria. After the first couple of days supply dumps and rest spots were very much hit or miss and those unable to continue began to drop out, being put out of their misery by guards. The survivors reached the small settlement of Ranau on 19 February. Of the 452 POWs who had set out 302 were now dead. On Anzac Day the base and its airstrip were bombed by American Lightnings and when the dust settled a number of prisoners and Japanese lay dead. The remaining Japanese garrison and 56 POWs abandoned the Ranau camp.

The second march began on 29 May 1945 with 536 POWs, nearly all less fit than the first contingent, setting off as before. When 183 survivors from this group reached Ranau on 24 June they found only six prisoners from the first march still alive.

Of the prisoners now left at Sandakan most were too ill to be moved. However, on 9 June 1945 it was decided to send 75 POWs on a final march. As each man collapsed they were despatched by guards.

Operations Python and Kingfisher

Plans for a rescue of POWs from North Borneo were first developed by the Services Reconnaissance Department (SRD), an Australian offshoot of the British Special Operations Executive (SOE). The history of the SRD was a mixture of outstanding success in Operation Krait but with significant failures, especially in Timor.

Operation Python commenced on 24 September 1943 when a six-man SRD team led by Major Gort Chester left Fremantle in the US submarine Kingfisher, arriving off Borneo at dawn on 6 October. Pre-war, Gort Chester was a rubber planter in Borneo and was fluent in Malay. Just three days after landing, in concert with local guerrillas they attacked the Japanese garrison at Jesselton killing all 50 defenders. A few days later a large Japanese force fought back ruthlessly crushing the revolt and killing many rebels and sympathisers.

Operation Kingfisher was established in early 1944 for training a parachute regiment in the Atherton Tablelands to deploy to North Borneo to stimulate local uprisings against the Japanese and release POWs. At this time USN patrols extended to North Borneo using Australian based submarines, and further reconnaissance was conducted by Catalina and Liberator aircraft. Despite extensive training of 640 Australian paratroopers the operation was eventually called off, supposedly owing to a lack of suitable aircraft.

The SRD conducted several further submarine reconnaissance missions in 1944 and 1945 and landed small parties which then contacted local resistance groups and helped in saving the lives of a handful of survivors. It is noteworthy that a similar American operation conducted in the Philippines in February 1945 was a resounding success.

Specially trained US Army airborne troops assisted by Filipino guerrillas attacked a fortified prison camp at Los Banos south of Manila, resulting in the release of over 2000 POWs.

Final Battles: Tarakan, Labuan, Balikpapan

Commencing with landings at Tarakan on 1 May 1945 and continuing through to the final Japanese surrender in August 1945, a series of Allied landings against the Japanese occupation forces in Borneo was known as Operation Oboe. Tarakan, a small island on the north-east coast, contained an airstrip which could be used for subsequent landings. With overwhelming support from American air and naval bombardment the island was quickly secured but with fierce opposition resulting in Australian casualties of 255 killed and 669 wounded; on the Japanese side 1540 were killed and 252 captured.

A similar attack was carried out on Labuan on 10 June and the area was secured at a cost of 34 Australians killed and 33 wounded, with 389 Japanese deaths and 11 prisoners.

The final amphibious assault of the campaign took place at Balikpapan on 1 July. The area was again secured at a cost of 229 Australians killed and 634 wounded with 2032 Japanese killed and 63 captured. The above figures do not include many civilian casualties.

The naval resources put into these landing were considerable. For example, at Tarakan troops were transported in HMA Ships Westralia and Manoora, with Hobart and Warramunga conducting pre-landing bombardment, supported by the frigates HMA Ships Burdekin, Barcoo and Hawkesbury, with HMAS Lachlan conducting hydrographic surveys.

Some would argue that at this late stage of the war these landings were unnecessary and of no strategic value. The Japanese here posed no threat and were preparing to surrender, and by waiting a while longer Borneo could have been secured without further destruction and casualties.

War Trials

Australian war crimes trials against the Japanese began in January 1946 with all trials held in open court. As the Australian Government did not wish to cause more grief to relatives of dead prisoners of war who had been subjected to appalling treatment by their Japanese captors the media agreed to provide only the briefest summary of events. Access is also denied to Army records detailing war crimes investigations.

Because of his phenomenal memory and ability to come across as a creditable typical Aussie soldier Bill Sticpewich was an outstanding witness. As a survivor his statements were invaluable, although he did have a tendency to present hearsay as actual evidence. The evidence given by some survivors was not helped by an element of perjury while seeking to implicate hated prison guards.

Sticpewich, who once described Nagai Hirowa as ‘one of the worst criminals’ had formally identified him at the Labuan compound. But at pre-trial hearing in Rabaul Sticpewich failed to denounce him so he was released. Sometime later in Tokyo, Sticpewich appears to have formed an alliance with Nagai Hirowa, as they contemplated writing a book together.

Australian authorities actively pursued war criminals until 1950. Of 898 names on the Borneo wanted list, 444 were arrested of whom 238 were released after interrogation. Of those tried for crimes committed against prisoners held at Sandakan and found guilty, eight were hanged and 55 received prison sentences ranging from two years to life imprisonment. Principal amongst these was the commanding officer of the Sandakan camp, Captain Susumi Hoshijima, who was hanged at Rabaul on 6 April 1946. Most of those imprisoned were released in the late 1950s.

The show trial of Lieutenant General Masao Baba, commander of the Japanese 37th Army and supreme commander of Japanese forces in Borneo, was held at Rabaul in July 1947. Evidence was presented that Baba was aware of the weakened conditions of prisoners, yet gave direct orders for the march from Sandakan to Ranau, causing many deaths. The trial resulted in General Baba being found guilty and sentenced to death. He was hanged at Rabaul on 7 August 1947, and this event concluded the Borneo trials.

War Graves

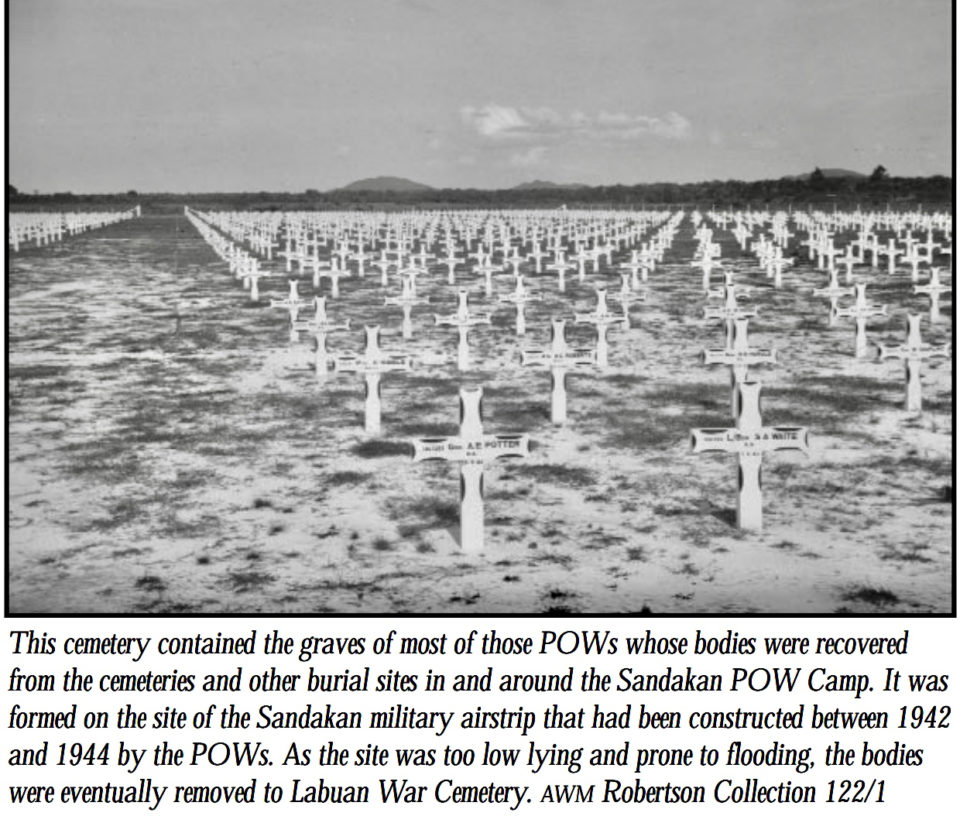

In March 1946 an Australian War Graves Unit (AWGU) was brought from Labuan to Sandakan and with the aid of a local workforce and Japanese prisoners began the mammoth task of clearing lush undergrowth from the Sandakan campsite. A site was selected near the defunct airstrip for a cemetery large enough to hold all the bodies which they aimed to recover from Sandakan and from the track to Ranau, as well as those killed in the more recent fighting at Labuan and Tarakan.

Owing to his local knowledge WO Sticpewich was seconded to the AWGU but he did not fit easily into the team and it was a relief when he left to give evidence to the International War Crimes Tribunal in Tokyo. In early 1947 Sticpewich returned and sought changes to the AWGU but was told quite bluntly he was not wanted and to return to headquarters. Back in Australia WO Sticpewich laid out his grievances to LTCOL Chapman, War Graves Director. As the AWGU manager in Borneo LEUT Brazier had now been demobbed, on 17 March 1947 Sticpewich achieved his objective, was promoted Lieutenant and returned to Borneo in charge of the War Graves Unit.

For all his faults Sticpewich was driven to produce results and was soon finding more bodies, and not content with that organised the re-excavation of two cemeteries that had been searched previously where more bodies were discovered. The final round up from Sandakan and Ranau was 2163 bodies had been discovered from the 2428 prisoners known to have perished in these camps or on the death marches. Given the environmental conditions this was a remarkable success rate.

Beautifully laid out with rows of pristine white crosses, the new Sandakan Cemetery was officially dedicated on Anzac Day 1947. But the existing lessons from the Japanese experience, that monsoon rains and poor drainage made this ground unsuitable, were not learned. As a result, all the remains had again to be exhumed and transferred to another cemetery at Labuan Island where they were finally laid to rest together with another 236 bodies from those who died in later fighting, mainly at Labuan and Tarakan.

For many years, before the extent of deaths attributed to the Sandakan POW camps was made public there were no memorials to these brave men. It was not until the early 1960s that the first public memorial to honour them was erected in Sabah (North Borneo). In 1985 another memorial was unveiled, also in Sabah, near the site of the Ranau compound. It is composed of smooth river stones, one for every POW who died on the marches to or at Ranau.

Meanwhile at home a memorial was first erected in 1989 by the Ku-ring-gai Council, in a park in the suburb of North Turramurra.

A Sandakan Memorial Park was built on the grounds of the former Sandakan prison camp in 1999 which commemorates all Australian and British POWs who suffered or died at the camp and on the death marches, as well as local people who risked their lives to help them. With the aid of an Australian Government grant the memorial has recently been upgraded and was expected to be reopened in April 2024.

Conclusion

The wartime experiences from Borneo warn us against the atrocities that can befall mankind with their testimonies of horror but again they show glimmers of hope telling inspirational stories of resilience.

During WWII some 22,000 Australian servicemen and women plus civilians became prisoners of the Japanese. Most were captured after the fall of Singapore and many were allocated to work camps including the infamous Thai-Burma Railway which resulted in a large number of deaths. But in terms of the worst overall number of fatalities the greatest tragedy to afflict Australian prisoners was in Borneo. Of nearly 2500 mainly Australian and British POWs at the Sandakan Camp in north eastern Borneo only six survived the war.

All these survivors left the Army shortly after returning home except for Bill Sticpewich MBE who made the Army his career, retiring as a Major in 1970. Sticpewich was the last survivor to escape from Ranau on 27 July 1945. He was killed by a motor vehicle while crossing the road in Melbourne on 18 March 1977 aged 68. The remaining survivors who escaped from Ranau: were:

Private Keith Botterill – 2/19 Infantry Battalion, escaped 7 July 1945 and who died on 26 January 1997 aged 74.

Bombardier Richard (Dick) Wallace Braithwaite – 2/15 Field Regiment, escaped 8 July 1945 who died on 2 December 1986 aged 68.

Gunner Owen Campbell – 2/20 Field Regiment, escaped 7 June 1945, the last of the survivors, who died in Adelaide on 3 July 2003 aged 87.

L/Bombardier William (Bill) Moxham – 2/15 Field Regiment, escaped 7 July 1945 who committed suicide in 1961when aged 61.

Private Merton Nelson Short – 2/18 Infantry Battalion, escaped 7 July 1945 who died on 13 July 1995 aged 75.

References

Gilling, Tom, The Witness, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2022.

Reid, Richard, Laden, Fever, Starved: The POWs of Sandakan, North Borneo, 1945, Commonwealth Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Canberra, 1999.

Silver, Lynette Ramsay, Sandakan: A Conspiracy of Silence, Sally Milner Publishing, Bowral, NSW, 2000.

ABC Podcast by Richard Fidler & Tom Gilling 2023: https://www.abc.net.au/listen/programs/conversations/bill-sticpewich-sandakan-pow-camp-tom-gilling/102184342?utm_campaign=abc_listen&utm_content=link&utm_medium=content_shared&utm_source=abc_listen