- Author

- Buckley, Lieutenant N.W. AM RNVR

- Subjects

- Biographies and personal histories, WWII operations

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2002 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

Bismarck slips shadowers

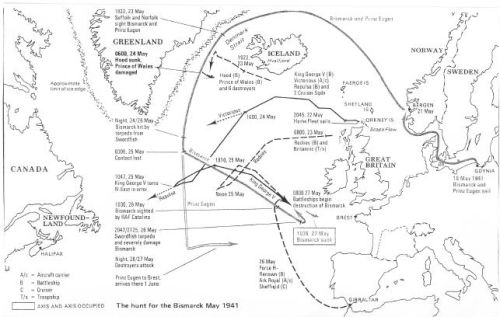

The Bismarck was followed for a while by a British cruiser but in the foggy conditions Bismarck managed to elude its followers and its location, somewhere south of Greenland, became a worrying mystery. Fortunately on 26 May at the end of a long search and through a hole in the clouds, a Catalina aircraft sighted Bismarck headed towards France.

She was attacked and her steering, and perhaps speed, were impaired by torpedoes from planes of the aircraft carriers HMS Ark Royal and Victorious. KGV travelling at 27 knots got to within 100 miles of the German battleship but, when joined by HMS Rodney (coming from Greenock), KGV slowed to Rodney’s maximum speed of 22 knots, which was the enemy’s estimated speed.

Bismarck closes KGV

Late that night when we were about 400 miles west of Brest (the French naval port) we learnt that Bismarck had turned towards KGV and that we would probably engage one another early the next morning. During the night both ships altered course at times to avoid getting too close during darkness. At daylight next day the battle began with KGV and Rodney attacking in unison.

I was on fire-watch duty below deck, so did not see Bismarck until, after some time, it had ceased firing and was leaning to port and on fire, with some of the crew jumping into the ocean. Bismarck did not hit either of the two British ships, possibly due to steering and stability problems arising from the earlier torpedo damage.

Disperse the battleships

As it was already known that Hitler had ordered a considerable number of aircraft and submarines to converge on the British ships, a British cruiser was told to hasten Bismarck’s sinking by torpedoes and the British ships dispersed as quickly as possible. KGV was in fact so short of fuel that she had to head for Loch Ewe in Scotland to refuel urgently.

Four months later, I started my very interesting officers training course in HMS King Alfred, followed by a shorter antisubmarine course in HMS Nimrod in Scotland.

In response to a question at the end of my training course as to what kind of a ship would I prefer to be posted to, I said I would like a smaller ship (thinking of one like a destroyer), but to my surprise I was posted to a convoy escort vessel, which was a converted ocean trawler.

Large trawler

HMS Northern Wave was larger than most trawlers (655 tons), with a greater length (200 feet) and a higher bow that enabled her to be kept at sea in the Arctic Ocean waters, even when the sea was very rough. So one felt reasonably safe from the natural elements even in stormy weather, provided that the bow was kept headed in to the wind and waves, the single coal-fired engine did not break down, and that, when you had to move fore or aft along the deck (you couldn’t do it below decks), you were able to dodge the rushes of seawater across the deck resulting from the waves coming over the very low freeboard.

Sometimes the seawater even penetrated the officers’ cabins and the crew’s mess-deck, as the ship rolled from side to side in a gale. She carried enough “black diamond” fuel to be able to stay at sea 12 or more days at a time. Her top speed was only about 11 knots but this was enough to keep up with most merchant ship convoys. She was armed with a four-inch gun and two anti-aircraft Oerlikon guns, and a load of depth charges.

Most of our convoy work was in the Western Approaches to Britain and between Britain and Iceland, but we were “sitters” to be chosen for the long Russian convoy trips because of the ship’s characteristics I have mentioned. I had the doubtful pleasure of being involved in two such return journeys: in April and May 1942 and in December 1942 to February 1943.

Convoy PQ14

My first such trip was as part of convoy PQ14 that took us 12 days to cover the 1800 miles between Iceland and Murmansk in Russia, starting on 8 April 1942. At that time of the year, there is quite a lot of daylight every 24 hours.