- Author

- Duchesne, Tim

- Subjects

- Ship design and development

- Tags

-

- RAN Ships

- None noted.

- Publication

- December 2003 edition of the Naval Historical Review (all rights reserved)

An historical and simplified account of how submarines eventually managed to charge their batteries without surfacing.

BY 1915, THE SUBMARINE was demonstrably, and for the first time, a weapon of war-winning potential when employed against an enemy dependent upon seaborne trade. It suffered however from many drawbacks stemming from its low mobility, especially when dived; in particular its short-range weapons and its dependence upon frequent use of the surface for access to the atmosphere limited its effectiveness. Submarines were thus little more than rather slow ‘mobile minefields’ so far as their tactical use was concerned.

By WWII, many improvements had been made in terms of firepower, mechanical reliability, diving depth and, marginally, mobility. The submarine’s advocates however continued to strive towards the concept of the ‘true submarine’ with high mobility and independence of the atmosphere for the duration of a lengthy patrol. We know now that only nuclear power made possible the realisation of this concept, but in the absence of this knowledge, designers and engineers continued to strive to make progress towards this goal.

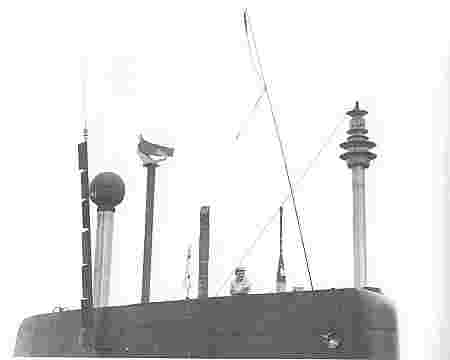

The Dutch were always bold, inventive and successful in submarine design and, true to form, developed a ‘ventilation tube’ or ‘schnorchel’, designed to permit the boats to run their engines whilst dived at periscope depth, shortly before the outbreak of war in 1939. It was actually fitted to the new construction ‘O-21’ and ‘O-22’. These boats completed in 1940 and escaped to Scotland for sea trials and workup just before the Netherlands was overrun. I do not know what, if any, trials were conducted on the ‘schnorchels’ in these boats, but the Admiralty decreed that they were neither reliable nor safe, and they were removed before the boats became operational.

O-27, on the other hand, was scuttled in Rotterdam, having been under construction (with ‘schnorchel’ fitted), when the Germans arrived. She was subsequently salvaged and became a German U-boat. The Germans also decided to remove the ‘schnorchel’ as being unsafe. There matters rested until airborne radar in particular finally turned the tables against the U-boats in 1943. Heavy German losses, despite electronic intercept equipment, stimulated their interest in the ‘schnorchel’ device and an improved version was incorporated in the design of the new high performance Type XXI boats. These were a significant step down the road towards the ‘true submarine’; with greatly enhanced battery capacity, high underwater speed (16-18 knots versus 8-9 knots) and the first successful ‘snorkelling’ (or ‘snorting’) capability.

They were the precursors of the British ‘T Conversions, Porpoise and Oberon classes, and the American ‘GUPPY’ – modified Fleet boats and subsequent non-nuclear classes. Fortunately, they and some Type VIICs, fitted with a more primitive version of ’schnorchel’, did not get to sea until 1944, by which time two years of appalling losses suffered by the U-boat Arm had resulted in severe dilution of experience and skill, whilst concurrently Allied Hunter-Killer Groups and ASW aircraft had achieved almost total mastery of the seas in the vicinity of convoys and in focal areas. Thus the Type XXIs were too late to influence the outcome of the war. Had they appeared in the Battle of the Atlantic about twelve months earlier the story could well have been very different.

The Germans were late in developing radar, and then only got surface gunnery sets to sea, whilst neither the Italians nor Japanese ever had production sets at sea. More importantly from the Allied submarines’ point of view, no Axis power developed airborne ASW radar. Thus there was no compelling reason for the British or the Americans to develop a ‘schnorchel’ (or ‘snorkel’ (USN) or ‘snort’ (RN)) system. Darkness provided concealment for their submarines, and charging on the surface at night whilst keeping a keen look-out presented few dangers except in summer in high latitudes, when darkness was of very brief duration. In contrast, from about 1943 in the Pacific, the USN’s Fleet boats were equipped with radar. This effectively turned night into day for them, whereas night remained impenetrable night for the Japanese.